Mississippi Today

On this day in 1952

April 14, 1952

Ralph Ellison's only novel, “Invisible Man,” confronted many issues facing Black Americans and became the first by a Black author to win the National Book Award.

Ellison told The Paris Review that Black history “is the most intimate part of American history. Through the very process of slavery came the building of the United States.”

Born in Oklahoma City in 1914, Ellison's father, who loved literature, died two years after he was born. Feeling they would have a better life in the North, the family moved to Gary, Indiana.

Ellison applied twice to the Tuskegee Institute and was finally admitted when the orchestra lacked a trumpet player. While he studied music there, he wound up spending free time in the library, where he read James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot's “The Waste Land” and Dostoevsky's “Crime and Punishment.”

Before graduating, he moved to Harlem, hoping to study sculpture. Instead, he met author Richard Wright and wrote a book review for him. Wright encouraged him to write fiction, and he did, first with a story inspired by hopping trains to get to Tuskegee. He went on to write what Time magazine and others called one of the best English-language novels of the 20th century.

The book begins: “I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.”

A number of characters and dialogue in “Invisible Man” came from or were inspired by oral interviews he did for the Federal Writers' Project during the Depression, including the line, “I'm in New York, but New York ain't in me, understand what I mean?”

Before “Invisible Man,” many books by Black authors aimed at protest, but Ellison aimed at broader themes and ideas.

“Why is it,” he wrote in an essay, “that so many of those who would tell us the meaning of Negro life never bother to learn how varied it really is?” The novel inspired a memorial in Harlem

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=349333

Mississippi Today

On Confederate Memorial Day, an honest annotation of the Mississippi Declaration of Secession

Today, Mississippi officially recognizes Confederate Memorial Day as the anchor of Gov. Tate Reeves-proclaimed Confederate Heritage Month.

Mississippi is one of just four states to still officially recognize the state holiday, which has been granted under gubernatorial proclamations from the past five governors. Notably, one cannot find Reeves' proclamation on his social media accounts; instead, you'd have to venture over to the Facebook page of Confederate States president Jefferson Davis' home if you want to read it, as first reported by the Mississippi Free Press.

The actual language of the Confederate Heritage Month proclamation appears benign at first glance. It opens with a reference to the start of the American Civil War in 1861 and follows with an acknowledgment of Confederate Memorial Day in Mississippi (more on that to come).

But the final paragraph, when examined with a critical eye, offers a reason for pause and concern. It reads:

“WHEREAS, as we honor all who lost their lives in this war, it is important for all Americans to reflect upon our nation's past, to gain insight from our mistakes and successes, and to come to a full understanding that the lessons learned yesterday and today will carry us through tomorrow if we carefully and earnestly strive to understand and appreciate our heritage and our opportunities which lie before us.”

Gov. Tate Reeves' 2024 Confederate Heritage Month Proclamation

The “if” in that passage is doing a lot of work. We can only learn from the past IF we embrace “our heritage?” That line then begs the question, “Whose heritage, exactly?”

The answer is obvious and makes an earnest reflection of the sins of the Civil War necessary. Despite the lofty verbiage of “insight” and “lessons”, the proclamation is a prop upon which the “heritage” of the Confederacy is elevated — a heritage defined by the institution of slavery.

This Confederate Memorial Day provides us an opportunity to take a deep dive into that heritage by carefully dissecting the document that most clearly outlines and defends it.

LISTEN: A Reading of the Mississippi Declaration of Secession

The Declaration of Secession was the result of a convention of the Mississippi Legislature in January of 1861. The convention adopted a formal Ordinance of Secession written by former Congressman Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar. While the ordinance served an official purpose, the declaration laid out the grievances Mississippi's ruling class held against the federal government under the leadership of President-elect Abraham Lincoln.

Below are a few annotated excerpts from the Mississippi Declaration of Secession.

The convention really couldn't be any more straightforward with the title and opening graf of their declaration. There is little to no ambiguity about the intent of this document, which is to say, “we are seceeding and this is why.”

If there is any doubt, simply toss the title into the thesaurus machine and see what you get…

“An Assertion of the Direct Causes Which Create and Excuse the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union“

Don't think there is much mystery there.

And there it is.

Despite the “states' rights” rhetoric of the Lost Cause myth, the convention makes it undoubtedly evident that slavery is the prominent reason for secession (just like they promised to do in the previous passage).

It offers a clear and concise answer to the question, “States' rights to do what?”

Read that passage again in your best Ron Burgundy voice. “It's science.”

But in all seriousness, one can't escape the blinding racism of this passage. Nor should one ignore how damaging the perpetuity of this unscientific, unrealistic understanding of the Black race and the Black body has been in the century-and-a-half since.

These lines are in reference to the federal government's attempts to block the expansion of slavery into new territories as the United States grew.

The Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 prohibited slavery in territories formed from the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30′ parallel.

The convention doubles down on the notion that secession is not only needed to preserve the institution of slavery, but quelch any attempts to deny its existence in emerging territories

Throughout much of the convention's list of grievances, the word “it” is used as a place-holder for the “hostility to this institution” that is mentioned in the previous excerpt. Or, to put it another way, “it” is the abolitionist movement.

Again, the racism is unavoidably clear. To the convention, advocacy for social and political equality for Black Americans is akin to promoting insurrection.

What comes after is a line that probably looks all too familiar to anyone who follows the ebbs and flows of grievance politics. The convention paints the press and schools as enlisted agents against them and their cause – the echoes of which are still heard today in regards to policies directed at systemic racism or the preservation of rights for the LGBTQ+ community. It's not a new addition to the playbook, and politicians who invoke this language are merely channeling their secessionist forefathers.

You have to appreciate the tone deaf irony of this bit. It's not the 435,000-plus enslaved Mississippians who are subject to degradation, but rather the wealthy, white ruling class.

This line also helps dispel the myth of the “compassionate slaveowner,” as it clearly indicates how slave-owning Mississippians viewed the enslaved — as a calculated asset in their ledgers, as a dollar figure, as potential lost property.

To top it off, the convention elevates its cause — the preservation of slavery — to a higher status than the causes for the American Revolution.

There is one thing the Declaration of Secession makes abundantly clear: slavery — the preservation and expansion of — is the prominent reason Mississippi and 10 other states seceded to form the Confederacy.

Reeves could very easily end the practice of recognizing April as Confederate Heritage Month. It's only made possible through a proclamation of the governor. All he has to do is say “no.”

But even if Reeves remains stubborn, the legislative branch wields enormous power, too. Mississippi's state holidays are codified, and lawmakers have the power to divorce Mississippi from a century-old practice of honoring Confederates and their cause. They can pass legislation ending Confederate Memorial Day on the last Monday in April. They can sever Robert E. Lee from the annual celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. on the third Monday of January. And they can let Memorial Day exist on its own as a federal holiday without doubly venerating Jefferson Davis on the same day.

For those keeping score, that's three Confederate-themed state holidays in Mississippi.

These holidays are rooted in the Jim Crow era. They stand side-by-side with laws and policies meant to deprive Black Mississippians of their economic and civic vitality. Reeves and lawmakers could choose to start down a path of rectification — remedying some of the ills of policies designed to keep certain Mississippians disenfranchised and destitute.

But for now, the holidays — and the reasons for them — remain. Slavery and the subjugation of Black people is the bedrock of Confederate “heritage.”

The origins of Confederate Memorial Day in Mississippi trace back to 1906, a time of Southern Redemption and the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan.

Ignorance cannot and should no longer be an excuse — certainly not in 2024.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1945

April 29, 1945

The memoir by Richard Wright about his upbringing in Roxie, Mississippi, “Black Boy,” became the top-selling book in the U.S.

Wrighyt described Roxie as “swarming with rats, cats, dogs, fortune tellers, cripples, blind men, whores, salesmen, rent collectors, and children.”

In his home, he looked to his mother: “My mother's suffering grew into a symbol in my mind, gathering to itself all the poverty, the ignorance, the helplessness; the painful, baffling, hunger-ridden days and hours; the restless moving, the futile seeking, the uncertainty, the fear, the dread; the meaningless pain and the endless suffering. Her life set the emotional tone of my life.”

When he was alone, he wrote, “I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all.”

Reading became his refuge.

“Whenever my environment had failed to support or nourish me, I had clutched at books,” he wrote. “Reading was like a drug, a dope. The novels created moods in which I lived for days.”

In the end, he discovered that “if you possess enough courage to speak out what you are, you will find you are not alone.” He was the first Black author to see his work sold through the Book-of-a-Month Club.

Wright's novel, “Native Son,” told the story of Bigger Thomas, a 20-year-old Black man whose bleak life leads him to kill. Through the book, he sought to expose the racism he saw: “I was guided by but one criterion: to tell the truth as I saw it and felt it. I swore to myself that if I ever wrote another book, no one would weep over it; that it would be so hard and deep that they would have to face it without the consolation of tears.”

The novel, which sold more than 250,000 copies in its first three weeks, was turned into a play on Broadway, directed by Orson Welles. He became friends with other writers, including Ralph Ellison in Harlem and Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus in Paris. His works played a role in changing white Americans' views on race.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Podcast: The contentious final days of the 2024 legislative session

Mississippi Today's Adam Ganucheau, Bobby Harrison and Geoff Pender break down the final negotiations of the 2024 legislative session's three major issues: Medicaid expansion, education funding, and retirement system reform.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=353661

-

Local News4 days ago

Sister of Mississippi man who died after police pulled him from car rejects lawsuit settlement

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

At Lake High School in Scott County, the Un-Team will never be forgotten

-

Mississippi Today1 day ago

On this day in 1951

-

Mississippi News2 days ago

One injured in Mississippi officer-involved shooting after chase

-

Mississippi News7 days ago

Cicadas expected to takeover north Mississippi counties soon

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Viewers make allegations against Hatley teacher, school district releases statement – Home – WCBI TV

-

Mississippi News Video5 days ago

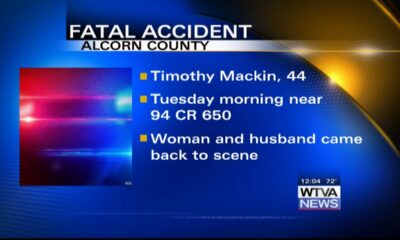

Vehicle struck and killed man lying in the road, Alcorn County sheriff says

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Ridgeland man sentenced for molesting girl