Mississippi Today

Mississippi’s child abuse pediatrician works between medicine and the justice system. Can he be objective?

Mississippi's child abuse pediatrician works between medicine and the justice system. Can he be objective?

This story is the first part in Mississippi Today's “Shaky Science, Fractured Families” investigation about the state's only child abuse pediatrician crossing the line from medicine into law enforcement and how his decisions can tear families apart. Read the full series here.

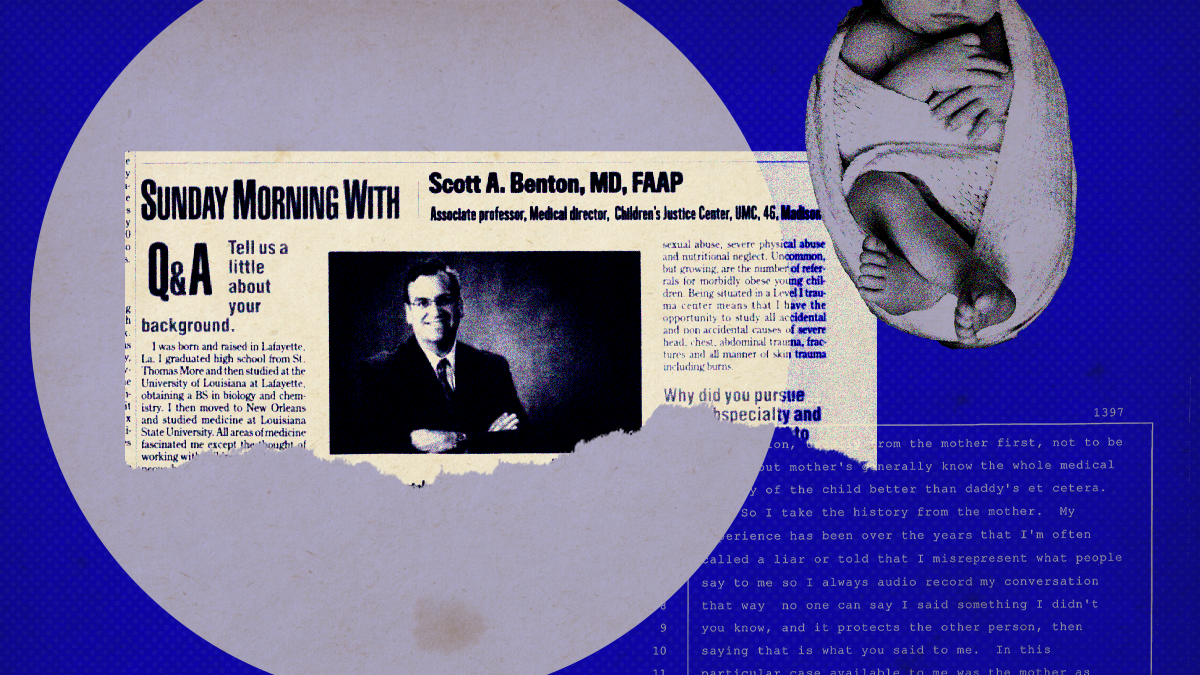

Dr. Scott Benton arrived in Mississippi in 2008 with a mandate to help ensure the University of Mississippi Medical Center stopped getting sued for failing to diagnose child abuse.

Dr. Dan Jones, then UMMC's vice chancellor for health affairs, had been troubled by the lawsuits following the hospital's oversights. Benton would later say that Jones wanted to know what the hospital could do to stop this from happening again.

The answer, in part, was Benton, whom Jones recruited to lead a new organization called the Children's Justice Center. Based at Children's of Mississippi in Jackson, the center's mission is to prevent and identify child abuse and neglect.

Right after he arrived, Benton led a two-year effort to develop a surveillance protocol for the entire hospital. Under the protocol, any child admitted to the hospital with trauma – like cuts or broken bones – is screened for potential abuse.

The center was renamed the Children's Safe Center and now has branches around the state where children can be examined for signs of abuse.

In the 14 years since Benton arrived in Mississippi, he has helped to change the state's policies, procedures and resources around child abuse. But the success of his center is difficult to measure as the evaluations he conducts are private, and abuse and neglect cases in youth court are sealed, too.

Benton's career parallels the growth of a unique medical specialty called child abuse pediatrics. Board-certified child abuse pediatricians must demonstrate knowledge of psychology, forensic medicine, neurology and much more. They say their combination of skills makes them uniquely able to determine when abuse has occurred.

Within children's hospitals around the country, child abuse pediatricians can investigate caregivers they suspect of abuse, make referrals to child protective services, and testify in criminal proceedings. Their work can save children's lives, and it may be particularly important in Mississippi, which had the country's highest rate of child deaths due to abuse or neglect in 2021.

But parents who say they've been wrongly accused, some doctors in other specialties, and sometimes even child abuse pediatricians themselves say the specialists can be too quick to allege abuse and insufficiently careful in considering other explanations.

And in Mississippi, where he is the only board-certified child abuse pediatrician, Benton has played a particularly powerful role in determining when parents are investigated for child abuse, with limited oversight or consequences for making accusations that are unsubstantiated.

Mississippi Today has uncovered three instances in recent years where parents allege he got it wrong.In each case, there were other explanations or potential medical conditions for the injuries the children exhibited that were not fully vetted by Benton or his team before their caregivers were accused of child abuse.

Parents are often unclear they are being investigated for child abuse when interacting with Benton and his team, they say. Benton said he and his team introduced themselves as “pediatricians from the Children's Safe Center.”

Benton, through communications officers at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, declined an interview request regarding this investigation from Mississippi Today. The communications officers responded to a limited number of a detailed list of questions and findings Mississippi Today shared with UMMC before publication and received statements from Benton but few direct responses or refutations.

“We walk a fine line between protecting abused children and protecting innocent parents,” Benton said in a statement. “I'm very cognizant of that. I emphasize that fact with staff, and I take that responsibility very seriously.”

In a separate statement, Dr. Mary Taylor, chair of the UMMC Department of Pediatrics, said Benton is “a respected member of our Medical Center staff” who has earned national certifications.

“As medical director of the Children's Safe Center, Dr. Benton has the difficult role of evaluating the evidence in cases of suspected child abuse in any form and rendering a decision based on his training, many years of experience and deep knowledge of the medical literature. He and his team of trained child abuse specialists provide evidence-supported medical opinions to many governmental agencies that are tasked with ensuring the safety of children. Often times, these children cannot speak for themselves and Dr. Benton's medical opinions are one part of a defined system of agencies that examine the totality of available evidence about suspected child abuse with the goal of protecting children from exposure to abusive environments.

“UMMC supports the critical work Dr. Benton does through the Children's Safe Center and values the service he provides to the state as the only board-certified child abuse pediatrician.”

A pediatrician's path evolves with a new medical specialty

Benton started his medical career in the 1990s, in his native Louisiana. His path in medicine evolved in tandem with the growth of a new medical specialty in child abuse.

During his second year of residency, he completed a clerkship in “pediatric forensic medicine” — what is now called child abuse pediatrics. He then took a job in pediatrics at the Louisiana State University medical school, which included training at the Center for Child Protection in San Diego, now called the Chadwick Center, and elsewhere.

Benton found himself at the center of a small but increasingly influential field. He became one of the charter members of the Ray E. Helfer Society, an organization of physicians who work on preventing and diagnosing child abuse.

“There's only a few of us that do this,” he once explained in a deposition. “We recognized that this was building up a body of knowledge that was greater than that of just a general pediatrician… We started thinking that we could possibly have a subspecialty in the late 90s, early 2000s.”

Benton and colleagues applied to the American Board of Pediatrics for the designation.

They argued they offered something unique: an ability to draw together insights from a range of specialties in order to diagnose a crime.

“You have to first show the fund of knowledge, what the factual bases are, you have to compile a full literature, as in any other subspecialty,” Benton said in a 2017 deposition.

In 2009, the board offered a certification exam for the first time. Benton holds certificate number 20 in child abuse pediatrics. Today, there are 330 board-certified child abuse pediatricians across the United States.

Around the country, child abuse pediatricians report suspected abuse and neglect to child protective services, and then may provide evidence to help the state remove a child from his or her family's custody. In some states, CPS also provides funding for their work.

Their credentials lend their determinations substantial weight in the eyes of CPS caseworkers, police, prosecutors and judges: A Marshall Project analysis found that reports of suspected abuse by medical professionals to child welfare agencies are 40% likelier to be substantiated than reports by non-medical professionals.

A ProPublica and NBC Investigation found thatonly about 5% of child welfare investigationsnationwide lead to determinations of physical or sexual abuse.

And around the country, Black children are disproportionately likely to be investigated. One2017 studyfound that half of all Black children in the US experience a CPS investigation by age 18, compared to less than a quarter of white children.

The three families featured in this series are white.

Benton has testified that his job requires him to “provide service to child protection, law enforcement and Mississippi prosecutors.” He started providing expert testimony soon after he began his medical career, first testifying in a case in September 1996.

Critics of this medical specialty — including defense attorneys and some doctors in other fields — argue that child abuse pediatricians are susceptible to bias because of their frequent and close interactions with law enforcement.

At one conference on shaken baby syndrome and abusive head trauma, a speaker presented defense expert testimony alongside a picture of Pinocchio. The event concluded with doctors and prosecutors singing a song mocking skeptics of the diagnosis to the tune of, “If I only had a brain.”

State public defender André de Gruy drew a parallel between child abuse pediatricians and medical examiners housed in the Department of Public Safety — both are scientists who say their work is objective, but who work closely with law enforcement and prosecutors.That may shape their interpretations.

“I think (Benton) is going to find abuse because he has a bias towards finding abuse, in my opinion,” de Gruy said. “In most of the cases, I suspect he finds abuse and there is abuse. But I think that there are the cases, the close calls, which is where the trouble comes in, where he's going to find abuse but someone else will look at it and not.”

Child abuse pediatricians and many colleagues in other medical specialties and fields like law enforcement and social work see their work as essential to identifying and intervening in cases of abuse. They say they follow the evidence.

Dr. Christopher Greeley, who leads the child abuse pediatrics team at Texas Children's Hospital, told NBC News that he and colleagues always work to rule out alternative explanations before making an accusation of abuse.

“We don't say, ‘Eh, take the kid away,' in a sort of flippant manner,” he told the news station.

Greeley, a past president of the Helfer Society who also chairs its public relations committee, did not respond to emails from Mississippi Today seeking an interview.

Mississippi's only child abuse pediatrician builds a new surveillance system

When Benton moved to Mississippi in 2008, the state was under pressure to improve protections for abused children. A federal lawsuit in 2004 charged that the state was failing to prevent abuse and neglect of kids in the foster system. In response, the Legislature created the Children's Justice Center in 2007, aiming to standardize and professionalize investigations of suspected abuse.

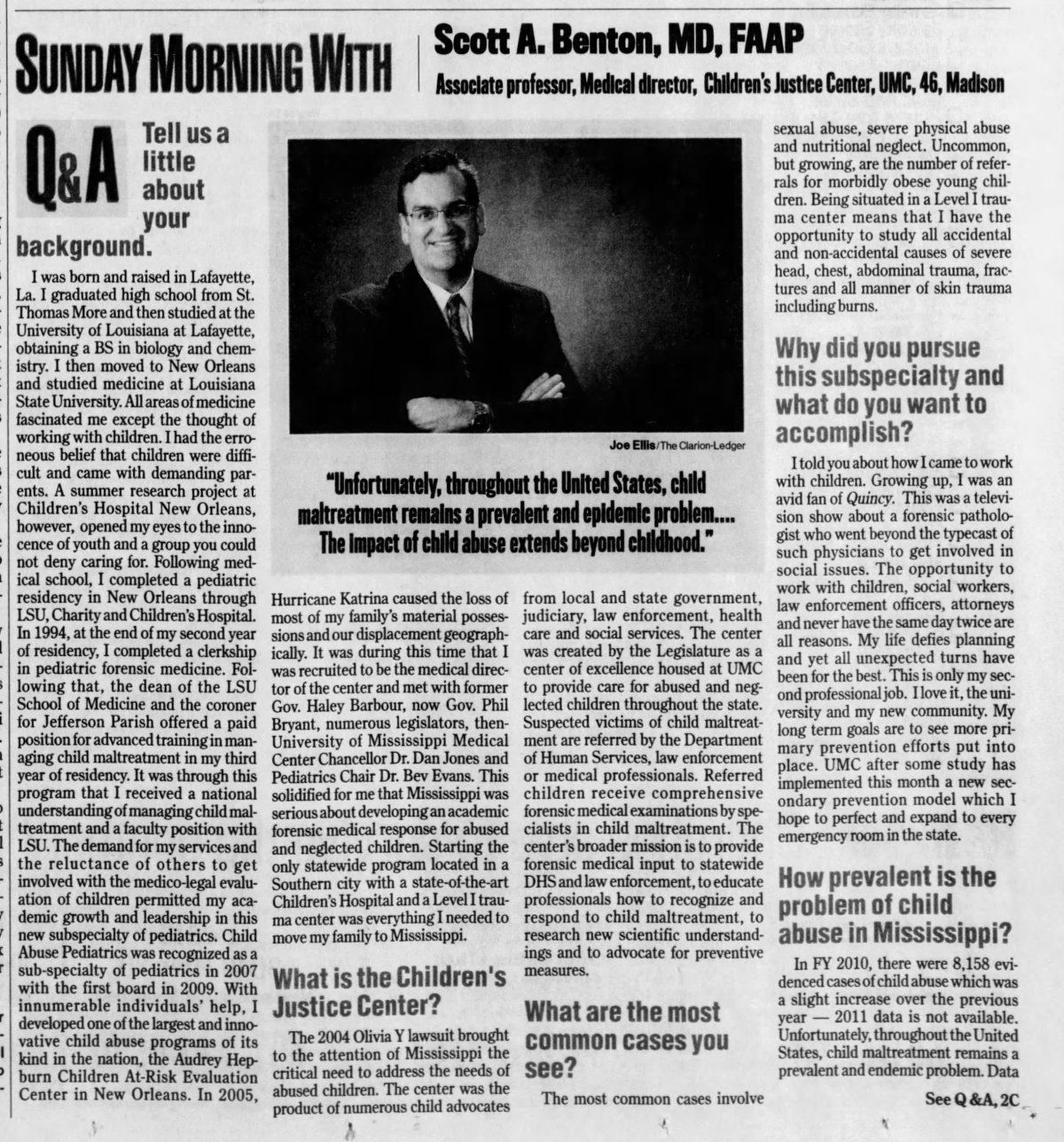

In an interview with the Clarion-Ledger in 2012, Benton explained that while working in New Orleans, he had developed one of the country's “largest and (most) innovative child abuse programs” with the Audrey Hepburn Children At-Risk Evaluation Center. But in 2005, Hurricane Katrina destroyed most of his family's material possessions and left them displaced from their home.

“It was during this time that I was recruited to be the medical director of the (UMMC) center and met with former Gov. Haley Barbour, now Gov. Phil Bryant, numerous legislators, then-University of Mississippi Medical Center Chancellor Dr. Dan Jones, and Pediatrics Chair Dr. Bev Evans,” he told the paper. “This solidified for me that Mississippi was serious about developing an academic forensic medical response for abused and neglected children.”

Benton's UMMC colleagues welcomed his arrival. Dr. Christopher Blewett, a pediatric surgeon who now works in Missouri, told Mississippi Today that before Benton came to the hospital, the bulk of the work to investigate child abuse and provide evidence during criminal proceedings fell to doctors like him because they were the ones who would see and operate on children with physical trauma sustained from abuse.

Benton, who also lived next door to Blewett when they were both in Mississippi, was “a godsend,” Blewett said. His training equipped him to recognize patterns of injury that could point to abuse, and he largely took over the work of testifying in court.

Blewett said he completely trusts Benton, whom he describes as devoted to his work. He recalled phone calls at 10 p.m. to discuss whether to release a family from the hospital or keep them another day or two so Benton, who frequently travels to testify in court, could interview them in person.

“Obviously it takes a special person to do that work,” Blewett said. “This is just short of like an SVU detective in many cases. It can be pretty grim at times.”

Benton made a similar point during his Clarion-Ledger interview. Other specialists are reluctant “to get involved with the medico-legal evaluation of children,” he told the paper.

In Mississippi, rates of child maltreatment are higher than the national average. And in recent years, the number of child deaths reportedly caused by abuse and neglect in Mississippi has risen, from 15 deaths in 2007 to 38 in 2020 and 49 in 2021. That year — the most recent year for which such data is available — the state had the country's highest rate of such deaths, at 7.07 per 100,000 children, compared to a national average of 2.46.

Today, Benton sees patients at the hospital suffering from severe trauma, supervises an outpatient sexual abuse clinic, and examines kids. Child Protective Services, police, lawyers, psychiatrists, pediatricians and emergency rooms refer children to the center.

Benton told Mississippi Today that the state's child abuse hotline receives about 30,000 calls annually, and about a third of these are substantiated. The Safe Center saw 2,400 children last year, he said.

He also implemented a “high-risk surveillance system,” under which Benton's team evaluates any child who comes to UMMC with certain injuries or symptoms. The triggers for such evaluation are wide-ranging, according to procedures obtained by Mississippi Today. They include any bone fractures, burns including “significant sunburns” and “all trauma warranting admission.”

Benton's mandate was to ensure hospital staff missed no warning signs for abuse.

“The general teaching previous to that time was not adequate to keep an open mind about whether parents or caregivers could be abusers,” he told attorneys for a defendant in a fatal child abuse case during a deposition.

The stakes are high on either side, he said. While an incorrect accusation can have serious consequences for a parent, failing to detect abuse can put a child's life at risk.

“I do think we try to get it right, and I'm not aware that there's any overcalling going on,” he said. “Nationally, if you look at the statistics on the epidemiology, it's always the opposite direction. We just take the person at hand and don't go any further.”

Benton has emphasized that the protocol for reviewing cases he implemented provides protections for caregivers and a systematic exploration of potential causes of injury.

“Before I came here, anyone they thought who had injured the kid was kicked out of the hospital,” he told a group of Mississippi public defenders a decade ago in a recorded presentation Mississippi Today reviewed.

“That was part of their protocol. And I said, ‘Alright, who am I supposed to get the history from? Who am I supposed to figure out whether there's a medical explanation for… some of these bleeding findings? So we quickly reversed that… We had to have multiple conferences to explain to them a concept you already understand: innocent until proven guilty … We've got several kids where we've made medical diagnoses where the nurses were like ‘Oh my God, I was ready to crucify this parent,' and the kid turned out to have a (inaudible) aneurysm in their brain that was mimicking head trauma.”

In an email to Mississippi Today, Benton said the surveillance system does not give him total decision-making power in every case.

“The high-risk surveillance system is a review of other professionals (sic) work and is not an independent investigation by the children's safe center,” he wrote. “However, if I feel by review that a case should be reported for state CPS investigation, I contact the medical provider involved in the case or the child's primary care provider and discuss my concerns with them. It is up to them at that point whether they agree with my concerns. This interaction is documented in the child's medical record.”

It is not clear whether Benton meant that the other medical providers in the case must make the decision to involve CPS. He and UMMC communications officials repeatedly declined Mississippi Today's interview requests and responded directly to only a small number of questions sent via email.

When Mississippi Today asked for clarification on this particular point, UMMC did not respond.

The law gives doctors and law enforcement an incentive to allege abuse any time it appears possible. It protects people who make a good faith report of abuse or neglect from any liability if they get it wrong, while failure to report can lead to a fine and up to a year in prison.

But Benton has said keeping “an open mind” does not mean jumping to conclusions about whether abuse has occurred. The Clarion-Ledger asked him what adults should do if they suspect a child is being abused.

“My first advice would be to not overreact,” Benton said. “Listen to the child.”

He encouraged “passive listening,” in which a caregiver repeats back what a child says in a questioning tone.

“Then be silent and wait for further response,” he said.

Once you suspect abuse, call the state child abuse hotline.

He also pointed to social factors that can contribute to abuse, like caregivers being out of work, displaced, or otherwise stressed. And most physical abuse, he said, is related to “inadequate parenting skills coupled with frustration.” Benton added that stressful situations involving feeding, crying and misbehavior could cause “an otherwise sane caregiver to lose patience.”

As the doctor charged with accusing caregivers of child abuse, Benton is acquainted with angry denials and furious criticism.

“My experience has been over the years that I'm often called a liar or told that I misrepresent what people say to me, so I always audio record my conversations,” he said on the stand during a 2014 trial. “That way no one can say I said something I didn't, you know, and it protects the other person.”

Two of the mothers featured in this series attempted to obtain the recordings of their conversations with Benton in the hospital but were unable. One was told she must have an attorney, and the other could not get in touch with an employee of the Children's Safe Center, where the recordings are housed.

A controversial diagnosis

Child abuse pediatricians like Benton are trained to recognize signs of abusive head trauma, formerly known as shaken baby syndrome (SBS), and often provide expert testimony in trials. For decades, three findings were considered indicative of the syndrome: subdural bleeding, retinal bleeding and swelling of the brain.

Questions about abusive head trauma comprise 10% of the certifying exam for child abuse pediatricians, more than almost any other topic on the exam. (Child fatalities and musculoskeletal injuries comprise 4% and 8% of the exam, respectively.)

Thousands of people in the U.S. have been convicted of shaking a baby to death since the 1970s.

Yet the scientific bases of the diagnosis are increasingly coming under question. A 1987 study reviewed 48 cases of “shaken baby syndrome” in the Philadelphia area and found that of the 13 fatalities, all had signs of impact, too. Biomechanical studies, including one published in 2022, have also found that forceful shaking of an infant will cause injury to the neck before the brain, although neck injuries have not been considered diagnostic of the syndrome.

Retinal hemorrhage, once regarded as conclusive proof of the syndrome, has been seen in infants who died from causes like meningitis or an obstructed airway.

Researchers have also found that short falls can generate much more force than shaking, and a 2001 study that looked at children's falls from playground equipment — but did not include infants — found that short falls could cause death, as well as retinal bleeding, and could be preceded by a lucid interval.

Critics of these studies say biomechanical models are not real infants. It's impossible to test the theory on babies.

The dispute over the science plays out in courtrooms around the country. The Washington Post reported in 2015 that at least 16 people in the U.S. had overturned their convictions since 2001, as judges determined that new information created reasonable doubt as to their guilt.

Indeed, a 2018 “consensus statement” published in the journal Pediatric Radiology was written in response to what the authors described as “speculative theories that cannot be reconciled with generally accepted medical literature” now being advanced during trials. The statement explained the injuries could be caused by shaking alone, shaking and impact, or impact alone.

“There is no controversy concerning the medical validity of the existence of AHT, with multiple components including subdural hematoma, intracranial and spinal changes, complex retinal hemorrhages, and rib and other fractures that are inconsistent with the provided mechanism of trauma,” the statement said.

The idea that shaking alone could cause fatal injuries in infants was introduced in 1971 by British pediatric neurosurgeon Norman Guthkelch. He published a two-page paper in the British Medical Journal titled “Infantile Subdural Haematoma and its Relationship to Whiplash Injuries” that established the link between shaking and head injuries in infants.

With his research, Guthkelch was attempting to solve a problem he kept encountering in his practice. Small children showed up to the hospital where he worked with bleeding on the surface of their brains, but with no broken bones or bruises to indicate they had been abused. He reviewed 23 cases of alleged child abuse, with subdural hematoma in 13. In five of those cases, there was no external sign of injury, and Guthkelch theorized their injuries could have been caused by shaking.

In the years that followed, doctors were trained to strongly suspect abuse if children came in with subdural hematomas, brain swelling and bleeding in the retinas. A guide to investigating child abuse published by the Justice Department in the late 1990s called retinal hemorrhage in babies “for all practical purposes, conclusive evidence of shaken baby syndrome in the absence of a good explanation.”

Prosecutors have won convictions with no eyewitnesses to the alleged shaking and no theory as to why the defendant would shake the infant, with little evidence beyond a doctor's diagnosis based on a supposedly definitive set of symptoms.

For prosecutors, shaken baby syndrome provides a tidy narrative: It is “a medical diagnosis for murder,” as Deborah Tuerkheimer, a law professor at Northwestern University and expert on shaken baby syndrome convictions put it in her 2009 article in the Washington University Law Review.

In 1996, Wisconsin day care provider Audrey Edmunds was convicted of murder in the death of a 7-month-old baby in her care. The prosecution's argument hinged on what was then regarded as medical fact: The presence of retinal hemorrhage, subdural bleeding and brain swelling — plus the absence of another explanation for those findings — provided a powerful indication the baby had been shaken. And the timing of the baby's decline purportedly proved Edmunds was responsible. Her defense did not challenge the science around shaken baby syndrome.

In 2008, however, Edmunds was granted a new trial. A judge determined that “a shift in mainstream medical opinion” on shaken baby syndrome meant a new jury could have reasonable doubt as to her guilt. The district attorney dropped the charges, and Edmunds was freed.

The outcome cast a spotlight on the controversy brewing over the diagnosis.

Guthketlch himself went on to express horror that prosecutors were using the diagnosis he had popularized to convict parents and caregivers when there was no other evidence of abuse. He spent the final years of his life reviewing controversial SBS cases and noted a high proportion of the children in them had a history of underlying illnesses or conditions that could explain their injuries, but that these issues were rarely considered in medical reports.

“While society is rightly shocked by any assault on its weakest members and demands retribution, there seem to have been instances in which both medical science and the law have gone too far in hypothesizing and criminalizing alleged acts of violence in which the only evidence has been the presence of the classic triad or even just one or two of its elements,” Gulthkelch wrote in a paper published in the Houston Journal of Health Law & Policy in 2012. “Often, there seems to have been inadequate inquiry into the possibility that the picture resulted from natural causes.”

In 2009, the American Association of Pediatrics issued a policy statement recommending doctors stop using the term “shaken baby syndrome” and instead use “abusive head trauma,” a terminology shift to describe the clinical findings instead of the mechanism of injury. The statement said injuries could be caused by shaking, impact, or some combination of both.

To critics, the name change presents an obvious problem: If the injuries can also be caused by impact, and defendants' accounts of what happened describe an accidental impact, how can doctors be certain the injuries were caused by abuse?

Child abuse pediatricians say the science of abusive head trauma is sound, and that when a child has a specific set of symptoms, a different diagnosis is unlikely. They argue that critics of the diagnosis are putting kids at risk.

“The controversy exists among just a few individuals predominantly traveling on the defense circuit, some of whom are making $600,000 a year providing testimony that is factually scientifically counterintuitive, counter science,” Benton said in one sentencing hearing in 2018, “so I wouldn't call that controversy when the people — I mean, you're making it as if it's balanced. Is it controversy? Yes, we're very upset when somebody misuses science in the furtherance of a child who in our estimation has been abused.”

Reading a newspaper, finding a homicide

When Benton arrived in Mississippi, he understood the Children's Justice Center had a decade of guaranteed funding thanks to the state's $100 million settlement with WorldCom Inc., a telecommunications company that collapsed in a multibillion-dollar fraud scandal. It turned out that was a drastic overestimate. Instead, he had a few years' worth of funding, and he had to look for other revenue streams.

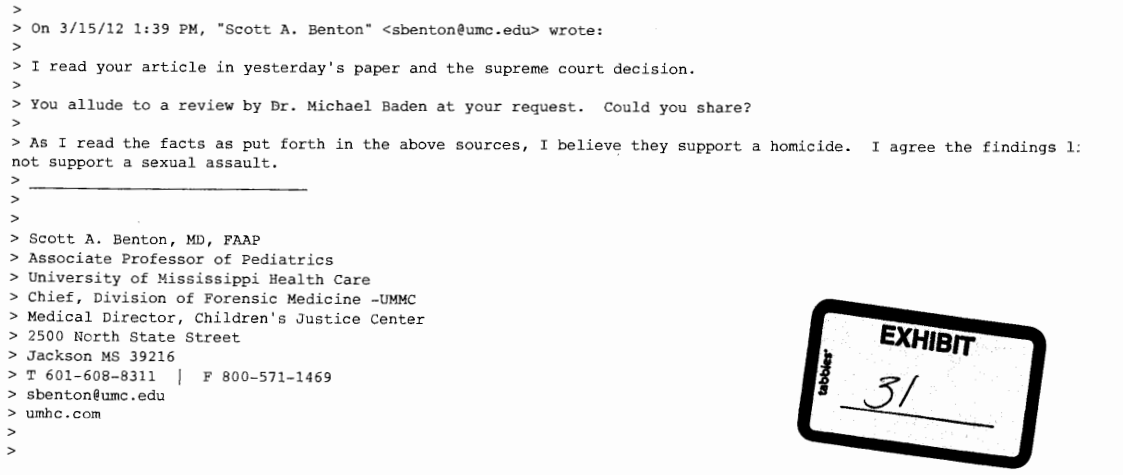

That was how the case of a man named Jeffrey Havard first came across his desk. Havard was convicted of capital murder in the death of his girlfriend's 6-month-old daughter in 2002, and sentenced to death. The prosecution's theory was that Havard had sexually assaulted the baby and shaken her to death.

The director of the center read a story in the Clarion Ledger about Havard's case by longtime investigative reporter Jerry Mitchell. The state Supreme Court had just rejected an appeal from Havard, but Mitchell had interviewed a pathologist who reviewed medical records and concluded there was no evidence of sexual assault or of homicide, and that the baby's injuries were consistent with Havard's claim that he had dropped her.

The center's director thought Benton could potentially apply his expertise to the case. Helping to right an injustice might boost name recognition and funding for the center.

But Benton didn't see an injustice.

“As I read the facts as put forth in the above sources,” he wrote to Mitchell on March 15, 2012, referring to the newspaper article and the state Supreme Court decision upholding Havard's conviction, “I believe they support a homicide.”

Mississippi Today health editor Kate Royals contributed to this report.

Editor's note: Kate Royals, Mississippi Today's community health editor since January 2022, worked as a writer/editor for UMMC's Office of Communications from November 2018 through August 2020, writing press releases and features about the medical center's schools of dentistry and nursing.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

MDOC promotes inmate boxing program, but lawmakers say money could be better spent

Boxing in sanctioned matches in a ring donated by rapper Jay-Z. Throwing and catching a football in the yard. Facing off in table tennis matches.

Sports teams have come to Missisisppi's prison system, giving incarcerated people a creative way to stay active, change attitudes, build sportsmanship and help in their rehabilitation, corrections officials said.

“We encourage our inmates to be involved in sports activities as it battles idleness in prison. We have created many different teams to allow them to get out of their dorms and participate in being active”, Commissioner Burl Cain said in a Wednesday news release.

Research has found that prison sports programs have social, mental and physical benefits, and participation in sports can help lessen detrimental health impacts people experience through incarceration.

But the bipartisan chairs of the Legislature's corrections committees are questioning why incarcerated people have been allowed to participate in boxing, which they say could create a violent environment and put the state on the hook for the boxers' medical care if they are injured.

House Corrections Chair Rep. Becky Currie, R-Brookhaven, and Senate Corrections Chair Juan Barnett, D-Heidelberg, said there are better uses of MDOC's budget than a sport as harmful as boxing.

They would rather see the department focus on a number of other efforts, including drug and alcohol treatment, job training and housing placements to prepare people to leave prison and not return.

“We have to make sure we're not teaching them to box,” said Currie, who is serving her first session as chair of the committee. “… This is not where we need to spend our time and our money.”

Barnett said incarcerated people should have access to recreation and time out in the yard, and he sees how supporters can see rehabilitative value in boxing and other sports teams. But those are less of a priority compared to MDOC's main role: to correct people, he said.

Boxing programs exist around the country in state and federal prisons, including in Louisiana.

The Angola State Penitentiary, where Cain served as warden, has a team. Henry Montgomery, who founded the program as an inmate, helped form the boxing teams there. Montgomery was released from prison in 2021 at the age of 75. His case led to the U.S. Supreme Court decision that all states were required to retroactively apply the ban on mandatory death-in-prison sentences for juveniles that it announced in its earlier Miller v. Alabama ruling.

In the news release, MDOC said the boxing team members are required to take drug tests and have a pre-match physical.

During the matches, medical staff and ringside trainers are present along with referees, timekeepers and official judges. Mississippi Athletic Commission Chairman Randy Phillips has helped with boxing training and is ensuring that MDOC's safety equipment meets standards, according to the news release.

Parchman's first boxing match was in November against incarcerated boxers who traveled to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman from the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility, according to MDOC. Creation of a boxing program at CMCF has been cited as a reason why the women were relocated from the 1A-Yard to unit 720 in 2022.

A pamphlet shared with Mississippi Today showcases a March 28 “Fight for the Title” event hosted at Parchman. Listed were the 22 members of the boxing team, 14 of whom fought in matches that day.

Tangya Allen-Elliott attended both boxing events to support her nephew, Carlos Allen, who coaches the boxing team. She said the March event had a good atmosphere and the matches seemed professional and safe.

Allen, 35, was appointed as the boxing team coach because of his leadership, Allen-Elliott said. Prior to incarceration, he played sports, refereed and coached.

He has been in the state prison system for three years and at Parchman for over a year, his aunt said. Allen was sentenced to over 100 years for drug trafficking, sale of fentanyl and possession of other drugs. Additionally, he was sentenced as a habitual offender, meaning he is not eligible for parole.

Being part of the boxing team has helped her nephew have a positive impact on others and mentor younger men – all of which give him hope in prison.

She said the sport is a great opportunity for the men, and she hopes it can serve as a guide for other states, such as Alabama, where she lives.

“They're on the right track,” Allen-Elliot said about boxing in Mississippi prisons.

“I had never seen a prison do something to this impact.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Medicaid expansion debate stirs memories of family medical debt for Mississippi senator

As clergy, physicians and business leaders have for weeks rallied at the state Capitol to expand Medicaid coverage to the working poor, observers can often spot the same conservative lawmaker listening attentively on the sidelines.

Sen. Chad McMahan, a Republican from Guntown, hasn't attended the events as a participant, a supporter or an opponent of the rallies. Rather, he goes because he wants to listen to the debate or because his constituents are there.

In fact, McMahan has been a quiet, yet constant supporter of Medicaid expansion, or Medicaid reform as he calls it. He believes the policy can give rural hospitals like North Mississippi Medical Center in his hometown of Tupelo a major boost and create a healthier population.

The three-term lawmaker is widely known for telling reporters that his main duty at the Capitol is to vote how the majority of the people in his district want him to vote. But he also openly shares his childhood story that he believes gives him a unique perspective on how steep medical debt can crush hard-working Mississippians.

When McMahan was in the ninth grade, he suffered an injury and had to be treated at the local emergency room. When the $20,000 bill came due for the medical services, though, there was a major snag: McMahan's family had no health insurance.

“That doesn't sound like a lot of money today, but in 1986, $20,000 would buy two top-of-the-line Chevrolet pickups,” McMahan said. “Today, it won't even buy a piece of a Chevrolet pickup truck.”

The legislator's father owned a cabinet-making business in north Mississippi, and his mother did clerical work. But the medical debt forced them to make tough decisions that thousands of Mississippians still face today.

It was impossible for the McMahan family to pay the bill in one swoop. Instead, they set up a payment plan with the hospital to pay the bill off over several years.

“It put a lot of stress and anxiety on my family,” McMahan recalled. “I saw my mom and dad having to decide at the dinner table whether they were going to pay a mortgage, buy groceries or pay the hospital bill that month.”

READ MORE: Medicaid expansion negotiators still far apart after first public meeting

Roughly 74,000 Mississippians don't make enough money to afford insurance, yet make too much money to qualify for Medicaid and find themselves in positions similar to the one the McMahan family was in decades ago.

But the state Legislature has a chance this year to address this issue because for the first time since the federal Affordable Care Act became law, it's considering expanding Medicaid to the working poor as the ACA envisioned.

The House and Senate this week are locked in negotiations on a final expansion bill after the two chambers passed vastly different proposals.

The House's initial plan aimed to expand health care coverage to upwards of 200,000 Mississippians, and accept $1 billion a year in federal money to cover it, as most other states have done.

The Senate, on the other hand, wanted a more restrictive program, to expand Medicaid to cover around 40,000 people, turn down the federal money, and require proof that recipients are working at least 30 hours a week.

The negotiators met publicly for the first time on Tuesday, but the six lawmakers remained far apart from a final deal. The Senate simply asked the House to agree to its initial plan. But the House offered a compromise “hybrid” model that uses public and private options to implement expansion.

McMahan said he personally supports the House's effort to expand to the full 138% of the federal poverty level, or an individual who makes $20,782 annually. But he also supports the Senate's effort to have an ironclad work requirement for the recipients.

While McMahan has compassion for uninsured people he doesn't think fiscally conservative Republicans should agree to expansion legislation that leaves out a work requirement or sets up a process for people to remain on the system indefinitely.

“I'm proud that I live in a country where there is a safety net to catch people and help people, but I'm not for turning the safety net into a hammock,” McMahan said.

The Senate negotiators were noncommittal on the hybrid compromise. House Medicaid Chairwoman Missy McGee scheduled a second conference committee meeting for Thursday afternoon.

McMahan applauded the House and Senate leaders for trying to come to a resolution on expansion, especially after the policy has been a nonstarter for the last 10 years at the Capitol.

He doesn't think it's his job to convince his Senate colleagues to change their minds. But he does want people who remain unabashedly opposed to the policy to listen to the stories of people across the state who still can't afford basic health care.

“I see the people who are out there,” McMahan said. “A lot of construction workers, a lot of fast food employees. I see the people who are working every day getting up and going to work who have never taken a hand out in life for anything who are not covered by health insurance.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

At Lake High School in Scott County, the Un-Team will never be forgotten

They were the 1974 Lake High Hornets football team, 29 players strong. But in Scott County, right there just off Highway 80, they are forever known, for good reason, as The Un-Team.

That's “un” as in: undefeated, untied, un-scored upon, and virtually un-challenged. The Hornets, coached by Granville Freeman, a maniacally demanding 26-year-old in only his second year as a head coach, out-scored opponents 312 to zero over 10 games. No opponent came within three touchdowns of Lake. This was before Mississippi had statewide high school football playoffs, but Lake was the undisputed champion of the old Cherokee Conference. The Hornets won the south division and were supposed to play French Camp for the league championship. Apparently, French Camp decided that discretion really is the better part of valor and declined to play.

Fifty years later, looking at the scores, it is difficult to blame them.

The 1974 Lake High School Un-Team

Undefeated, un-tied, un-scored upon

Lake 18 | Choctaw Central 0

Lake 20 | West Lauderdale 0

Lake 40 | Stringer 0

Lake 30 | Beulah Hubbard 0

Lake 54 | Sebastopol 0

Lake 42 | Hickory 0

Lake 20 | Scott Central 0

Lake 30 | Nanih Waiya 0

Lake 20 | Clarkdale 0

Lake 38 | Edinburg 0

Lake 1 | French Camp 0 (forfeit)

Twenty-six of the 29 Lake Hornets are still living, and all 26 will be back in Scott County this Saturday night to be honored by the Scott County Sports Hall of Fame at Roosevelt State Park. They will come from nine different states and one will return home from Germany. They wouldn't miss it. Would you?

Said Freeman Horton, the team's best player, who later was a four-year starter at Southern Miss, a longtime coach, and now lives in Horn Lake, “We achieved something back then that can never be surpassed. Some other team, somewhere, might tie our record, but I doubt it. One thing's for sure, they can't beat it. There's no way.”

Coach Granville Freeman was an old school coach in some ways but decades ahead of most high school coaches in so many others, as we shall see. “When I went to Lake in 1973, I told them we would have a team that when opponents got ready to play us, they would be shaking in their shoes,” Freeman said. “I'd say we accomplished that in 1974.”

Old school? Lake ran out of a straight T-formation, nothing fancy. The Hornets played a standard four-man front defensively. Freeman demanded all-out effort, all the time. He drove the team bus to practice 5.3 miles away from the school. After what was usually a long, tortuous practice if he wasn't satisfied with the effort or performance, he followed in the bus, lights on, while the players ran all the way back to the high school. If they were going too slow, he'd rev the engine. If that didn't work, he might even bump a straggler's rear end.

“You couldn't do that these days, could you?” Freeman said, chuckling. “I'd need a really good lawyer.”

He would also have needed a jury made up of avid Lake football fans who knew there was method to his madness.

There's no doubt Freeman worked at least as hard as his players. Said Harry Vance, the team's quarterback, “Coach was 25 years ahead of everybody else in the way he used film and developed scouting reports. By the time we met as a team after church on Sunday, he had graded Friday night's film and had a 20-page scouting report prepared and printed on the next opponent. It was only Sunday and we already knew everything we were going to do.”

Said Vance of his coach, “He coached 24 hours a day, seven days a week. And he was crazy smart.”

Horton, who starred as an outside linebacker on defense and left tackle on offense, was widely recruited. Mississippi State, Ole Miss and Southern Miss all offered scholarships. So did Bear Bryant at Alabama, and this will tell you much about Granville Freeman's crazy intellect. Bryant and Ken Donahue, his top recruiter, visited Lake to recruit Horton. Freeman was discussing Horton with Bryant and Donahue after practice when Donahue asked, “Coach, I don't understand why you don't you play your best athlete at middle linebacker? At Alabama, Horton would be playing in the middle.”

Responded Freeman, “Well, Coach, I'll tell you why. If I line up Horton in the middle, I don't have any idea which way the other team is gonna run. But if I line him up one side, I know for damn sure which way they ain't about to run. This way, we only have to defend half the field.”

Freeman says he looked over at Bryant. The legendary, old coach was chuckling, as he told Donahue: “Well, now you know, Coach, makes a whole lot of sense to me.”

Many in Lake thought Freeman really had lost his mind during the spring of 1974. That's when he called his players together and told them summer workouts would be different that year. Twice a week, a ballet teacher was going to come from Jackson and work them out in the gymnasium. Yes, they were going to take ballet lessons, and they would each pay for the lessons. “We thought Coach Freeman was nuts when he told us about it,” said Dewey Holmes, the team's star running back who rushed for more than 1,200 yards. “But we all did it.” These weren't rich kids, mind you. Many of the Lake players picked up aluminum cans on roadsides to earn the money to take ballet.

It made all kinds of good sense to Freeman. “Ballet is all about balance, about footwork, about flexibility and core strength,” Freeman said. “I thought it was perfect training for a football player. We called ourselves the twinkletoes Hornets.”

A lot of folks laughed when they heard about it. They weren't laughing a few months later, not after 312-0.

And nobody was laughing in the locker room at halftime of a game at Hickory. Lake led only 7-0 and Freeman was furious. So, he yanked the helmet off one player and threw it through a window. “I surprised myself with that,” Freeman said. “I thought, ‘Now, I've done it.'”

So he did it some more. He grabbed more helmets, threw them through more windows. Final score: Lake 42, Hickory 0. Of course, Hickory wanted those windows fixed and when the bill arrived, Lake Hornets fans raised the money to pay.

Another time, after a scoreless first half with Stringer, Lake players feared what would happen in the locker room. They expected another tirade. Instead, Freeman walked in and told them he was so disgusted he was quitting on the spot. So, he walked out of the locker room and took a seat in the stands. And that's where he was when the Hornets returned to the field and proceeded to score 40 straight points.

Many readers might wonder what happened to Granville Freeman, so wildly successful, so early in his coaching career. Answer: Four years later, he retired from coaching at age 30 with a 57-2-1 record.

Why? Burnout was surely one reason, and there were at least 485 more. His last monthly paycheck at Lake was for $485. Said Freeman, I did the math and figured out what I was making per hour. I was coaching the junior high and high school teams, mowing and lining the fields, watching film, carrying it to Jackson to be developed, doing scouting reports, washing uniforms, running the summer program, teaching, driving the bus. It came out to 17 cents an hour. I wasn't sleeping much.”

As many coaches in Mississippi have, Freeman stopped coaching and started selling insurance. Fourteen years ago, when he explained the reasons for his his early retirement from coaching, the interview was interrupted when someone knocked and slipped a payment under the door of his State Farm office. Freeman never missed a beat, laughing and telling this writer, “You know, that right there never happened back when I was coaching.”

Now 77, he has retired also from State Farm. The insurance money was far better in those later years but nothing ever happened to come close to the satisfaction of that unparalleled autumn half a century ago.

Undefeated. Un-tied. Un-scored upon. Perfect. That's why all 26 living players are coming back. That's why end Dexter Brown is traveling from Frankfurt, Germany, to take part. That's why Holmes, the star running back who later rose to the rank of full-bird colonel and traveled the world in the U.S. Air Force, is coming from his home in Tucson, Ariz.

“We grew up together, we achieved together,” Holmes said. “I wouldn't miss this.”

So many stories will be told, none more than what follows.

Nobody had come really close to scoring on the Lake Hornets until the final game, when a fourth quarter fumbled punt gave Edinburg the ball at the Lake 8-yard line. Three plays later, the ball was still on the 8, and Edinburg, trailing 38-0, lined up for a field goal. Moochie Weidman, the Hornets' nose guard who might have weighed 140 pounds, broke through the center of the line so quickly he blocked the kick with his chest.

How did it feel, someone asked Moochie, after he regained his breath. He answered with a grin. “It hurt so good,” he said.

Freeman Horton says it remains probably his favorite memory of that un-season. “Moochie was our smallest guy, the one you'd least expect, and he was the hero,” Horton said.

Sadly, Moochie Weidman is one of the three deceased 1974 Lake Hornets, but he will be remembered, ever so fondly, Saturday night.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

228Sports5 days ago

From Heartbreak to Hoop Dreams: Pascagoula Panthers Springboard from Semifinal Setback to College Courts

-

Mississippi News5 days ago

2 dead, 6 hurt in shooting at Memphis, Tennessee block party: police

-

Local News14 hours ago

Sister of Mississippi man who died after police pulled him from car rejects lawsuit settlement

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Forest landowners can apply for federal emergency loans

-

Mississippi Today14 hours ago

At Lake High School in Scott County, the Un-Team will never be forgotten

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Burnsville man arrested in Prentiss County on drug related charges

-

Mississippi News3 days ago

Cicadas expected to takeover north Mississippi counties soon

-

Mississippi News2 days ago

Viewers make allegations against Hatley teacher, school district releases statement – Home – WCBI TV