Mississippi Today

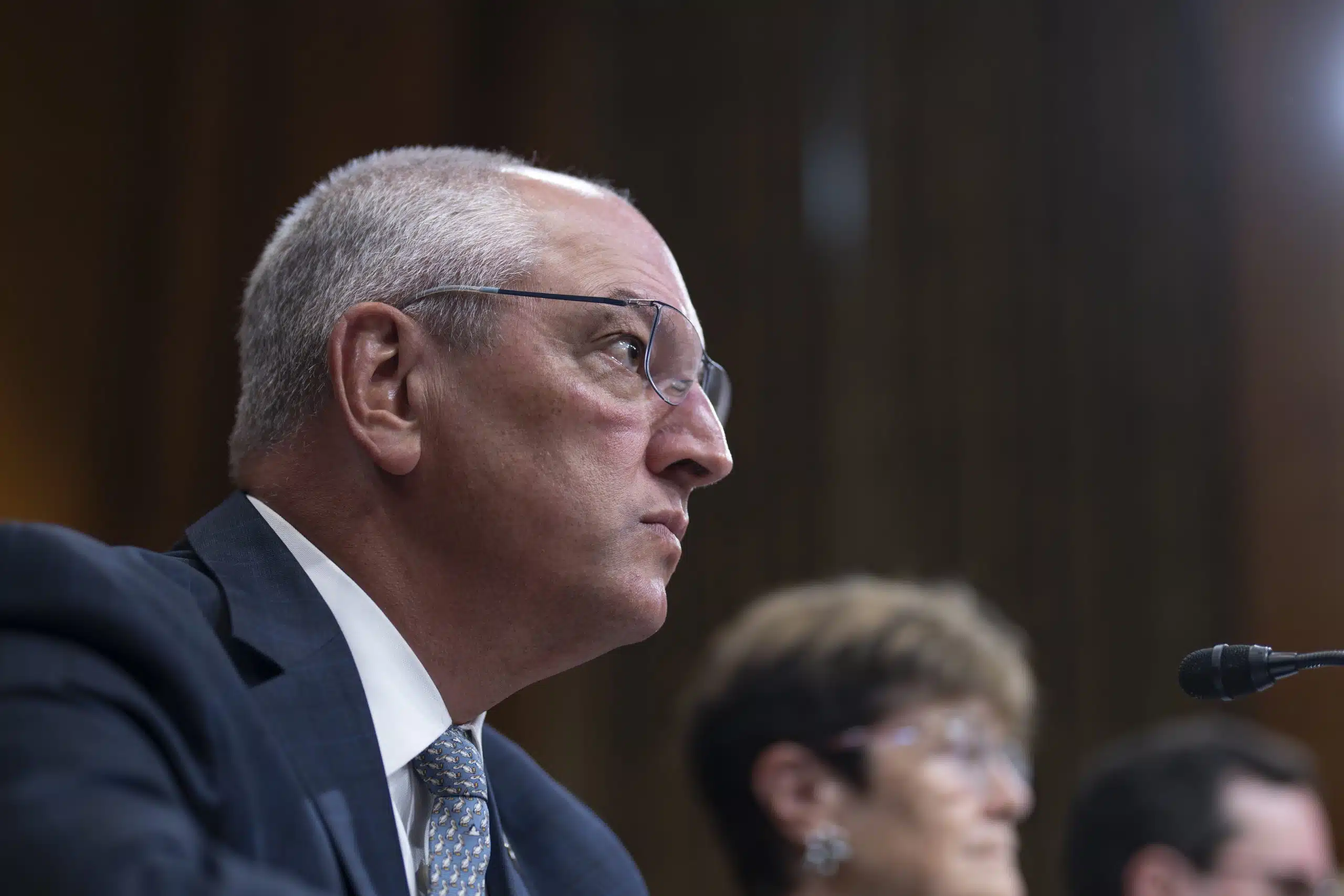

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards: Medicaid expansion ‘easiest big decision I ever made’

Two-term Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards calls expanding Medicaid as he took office in 2016 “the easiest big decision I have ever made” — and one that has had clear and convincing positive results for Louisianans.

“To me it was an obvious no-brainer, and maybe it’s easier for me to say that than others because I believe in making government work,” Edwards said in a recent interview with Mississippi Today. “I don’t believe in just saying, ‘Well, we just don’t want to expand government.’ Quite frankly, I don’t expect St. Peter to ask that question one day: Did you expand government? But I do expect him to ask what I did for the least fortunate among us.”

Louisiana, like other states nationwide, was at the time facing a health care crisis. It led the nation in rates of uninsured people — 22%-23%, mostly the “working poor.”

“We had many hospitals, especially rural hospitals, that were in danger of closing when I became governor,” Edwards said. “But because we have expanded Medicaid, we have not lost a single one.

“I’m not going to try to tell you that it fixed all of our problems and that all of a sudden we have the best health outcomes in the country,” Edwards continued. “What I can tell you is it addressed our most pressing problems, and it has created an environment where we can more easily produce better health outcomes because you just have more people with the ability to go to a doctor.”

Edwards said that when he became governor of Louisiana in 2016, the politics of Medicaid expansion "were probably about the same" as they are now in neighboring Mississippi, and so was the dire health care situation. He would unequivocally recommend Mississippi leaders take advantage of the federal program designed to help poor states with health care.

READ MORE: ‘A no-brainer’: Why former Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe successfully pushed Medicaid expansion

Edwards notes the politics on expansion have changed in Louisiana.

"In Louisiana we have a gubernatorial campaign underway, and I don't believe there is a single major candidate of either party who says anything other than they will leave the Medicaid expansion in place."

Mississippi Today interviewed the term-limited Gov. Edwards on Medicaid expansion as the end of his term nears, on a policy he says "ranks at the very top" of his accomplishments. The interview is below, edited for brevity.

Mississippi Today: Could you give a brief/broad overview of the situation when you took office, and of the impact Medicaid expansion has had in Louisiana since 2016.

Gov. John Bel Edwards: First, I'll talk about the impact it's had on our overall state budget. Secondly, individuals and families — many for the first time — have health insurance. And thirdly, we saw positive impact on the financial bottom line of hospitals across our state.

When I became governor, we had the largest general fund budget deficit in our state's history. It exceeded $2 billion for the first full fiscal year that started July 1, 2016, and that was a little more than 20% of all our state general fund. And that deficit occurred after several years of leading the nation in cuts to higher education, and cuts to basic health care delivery systems in our state.

And the cuts were just horrible with respect to Medicaid ... You have optional programs, but the optional programs were like hospice, end-stage renal disease care — things that most people would never consider optional, like things that would impact a person's ability to stay in a nursing home.

The people who were caught uninsured were working poor people. The poorest of the poor qualified for Medicaid. Those who worked and made enough money had private insurance or employer sponsored insurance. Working poor people were left out of that equation, and our uninsured rate among working aged adults was the highest in the country, around 22%-23%.

If someone is uninsured and they have access to any health care, it's likely to be an emergency room, which is the most costly way to receive health care. It's also the least effective way to manage disease ... That care either went totally uncompensated by the health care provider, meaning they had to pay for its themselves, or it might have been compensated in part by the (federal-state Disproportionate Share Hospitals) program.

But the DiSH program costs the state about 40 cents on the dollar. Medicaid expansion has never cost more than 10 cents on the dollar, and in Louisiana, the 10 cents is actually borne by the health care providers themselves because the hospitals realized their bottom lines would benefit so much that they assessed themselves.

This has produced an awful lot of compensation for these hospitals. Their bottom line is so much better — and this is all hospitals, our community hospitals, our very large hospitals like Ochsner, like Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady, like Children's Hospitals of New Orleans. But also, and I suspect most importantly, rural hospitals, because they were the ones struggling the most just to keep their doors open and routinely cutting programs and reducing staff to stay afloat.

We were able to address all of that through the Medicaid expansion, and it helped our state budget tremendously. My predecessor said he refused to expand Medicaid because we couldn't afford it. The truth is we couldn't afford not to do it. It actually helped our bottom line and allowed us to shore up the financing of our hospitals.

But it also helped these working poor people because many of them for the first time in their lives had an insurance card in their pockets ... As the medical community here has told me many times, it saved a lot of lives here in Louisiana ... I believe that Medicaid expansion is a pro-life position.

MT: Did Louisiana see an increase in gross domestic product from Medicaid expansion?

Edwards: We had GDP gains. I can't say it's because of Medicaid expansion or that it's responsible for X percentage of that, but I can tell you we have had the highest personal income ever. We have had the lowest unemployment rates ever and we have had the most people working ever. We have had tremendous growth in our GDP, and I just intuitively know it helped.

... By getting away from all that uncompensated care and the matching payments we had to put up, and because hospitals assessed themselves to cover the 10% costs, we were then able to use the budget savings and the money we had to address other pressing concerns that we inherited after a long period of disinvestment in our state. It allowed us to invest in other critical priorities.

MT: How has expansion affected Louisiana’s workforce?

Edwards: So, you have a relationship with a primary care physician. You have routine appointments and diagnostic evaluations, breast cancer screenings, prostate cancer screenings ... Your disease gets diagnosed earlier. Your treatment starts sooner, and it comes with a prescription benefit, so you have a way to be healthier. You're a more productive worker. You're less likely to be laid off. You're more likely to be able to support your family. That business has a healthier employee who shows up to work more often and is more productive — and the business didn't have to pay for it.

I’ve had employers tell me they had good employees, but they weren’t necessarily healthy. They had a disease. They didn’t have health insurance, so they had to miss work to go and wait around an emergency room. They would have to call in sick more often. These employers benefit from having a healthier, more productive workforce that doesn’t come at their expense.

When you expand Medicaid for the working poor, you also work with the health care providers so that they don’t just have appointments 9-5 Monday through Friday, but you work with them so they have appointments after hours during the week, have places they can go on the weekends so that they don’t have to miss work in order to access basic care.

Now we have the advent of telehealth, which can be covered through the Medicaid program and allow them to see doctors and even specialists without having to travel. That is particularly onerous for poor people in rural areas that lack the resources and also are furthest away from the nearest physicians that they need to see.

MT: Has expansion had an impact on mental health and-or substance abuse?

Edwards: It comes with behavioral health benefits for mental health, and it also comes with benefits for those people who have addiction disorders, and those benefits both in patient and outpatient. That's clearly something we still don’t have enough of, but we have a lot more services available now than we ever did before.

MT: What is your take on Mississippi's battle over expanding Medicaid and its ongoing hospital/health care crisis? What advice would you give to Mississippi – particularly its politicians and leaders – on Medicaid expansion?

Edwards: I don’t think the whole time I have been governor I have addressed comments critical to another state or the leadership of another state. I will say the situation there, the one that I read about and the one that I know a little bit about firsthand — my wife is from Wayne County, Mississippi, and all of her family is still up there — it looks an awful lot like the situation we had here. The politics were probably about the same here.

... Here in Louisiana, we decided that decision was made by the federal government when they passed the Affordable Care Act — otherwise known as Obamacare — a feature of which was Medicaid expansion. So that decision was made by the Obama administration and the Congress at that time. It hasn’t been repealed, so it remains available to states, although not mandatory as it was originally intended. I believe that we should try to make government work for those who need it the most. The working poor people certainly need health care.

I believe that you should make available to your state federal programs that not only do that, but provide a benefit to your budget so that you can then have the flexibility to address other pressing concerns as well. We were able to do that here. Obviously the situation as it exists in Mississippi to the extent that I am familiar with it — I'm rather familiar — looks an awful lot like what we had here in Louisiana.

I would certainly recommend Medicaid expansion to the Legislature there, to the governor there, to the people who are running for governor there. I would recommend it to Gov. Reeves, to Brandon Presley and to everyone else.

MT: How is expansion viewed across the aisle now in Louisiana? What level of opposition remains there? Any chance Louisiana voters would go along with undoing expansion?

Edwards: Obviously people might expect me to give a full throated defense of Medicaid expansion. I was a champion of it while Gov. Jindal was in office and refused to do it. I ran for office saying I was going to do it, and I have since done it. I would just invite anybody to come over here and talk to the hospital association, talk to hospital medical directors and CEOs.

Go to the most rural isolated, poorest parts of our state ask them about Medicaid expansion, and then go talk to employers in those areas and see what a difference its made for them.

The opposition has just melted away here. It's virtually nonexistent. I think that’s borne out by the campaign that’s underway where not a single candidate says they would undo the Medicaid expansion, and it would be a perilous position for them to take in the campaign if they said that.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=279342

Mississippi Today

Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling.

A Jackson County Chancery Court judge is denying the public access to a case that involves several politically connected Mississippians and their failed venture to ticket uninsured motorists using cameras and artificial intelligence.

Media companies Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald have filed for relief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Chancery Judge Neil Harris improperly closed the court file without notice and a hearing to consider alternatives. The media outlets say the court file should be opened.

Mississippi Today in June filed its motion asking that Harris unseal the case, which he denied six days later.

Gulfport attorney Henry Laird writes in the media companies’ petition for state Supreme Court review, “The Chancery Court sealing the entire court file both before and after Mississippi Today’s motion to unseal the file violates the public and press’ cherished right of openness and access to its public court system and records.”

Mississippi judges have long followed a 1990 state Supreme Court decision that says, “A hearing must be held in which the press is allowed to intervene on behalf of the public and present argument, if any, against closure.”

Instead, Harris said he found no hearing necessary after reviewing the pleadings to open the file. The case, he said, is between two private companies.

“There are no public entities included as parties,” he wrote, “and there are no public funds at issue. Other than curiosity regarding issues between private parties, there is no public interest involved.”

The case involves what is usually a public function: Issuing tickets to the owners of uninsured vehicles. And, according to one party to the case, the Mississippi Department of Public Safety is owed $345,000 from the uninsured motorist program.

READ MORE: Private business ticketed uninsured Mississippi vehicle owners. Then the program blew up.

Since the entire court file is closed, the public is unable to see why the judge sealed the case. The Mississippians said in the Chancery Court case that they have “substantial” business interests to protect and “a lot of political importance,” an attorney opposing them said in a related federal case that is not sealed.

Georgia-based Securix LLC signed up its first Mississippi client in 2021, the city of Ocean Springs, an agreement with the city showed. Securix developed a program that uses traffic cameras, artificial intelligence and bulk data on insured motorists to identify the owners of vehicles without insurance.

To sign on other Mississippi cities, Securix enlisted three well-known consultants, Quinton Dickerson, Josh Gregory and Robert Wilkinson. Dickerson and Gregory are Republican political operatives in Jackson who have run numerous state and local campaigns and advise many of the state’s top elected officials. Wilkinson, a Coast attorney, has represented local governments and government agencies, including the city of Ocean Springs.

MS business partnership sours

In 2023, the Mississippians formed QJR LLC. Their company entered a 50-50 partnership with Securix called Securix Mississippi.

Securix Mississippi sold the cities of Biloxi, Pearl and Senatobia on the uninsured driver program.

Fees collected from uninsured drivers were apportioned to the company, the cities and the Department of Public Safety, the operating agreement with Biloxi showed.

The citations offered three options, according to copies included in a federal lawsuit filed by three Mississippi residents who received them:

- Call a toll-free number and provide proof of insurance.

- Enter a diversion program that charges a $300 fee and includes a short online course and requires agreement that the vehicle will not be driven uninsured on public roadways.

- Contest the ticket in court and risk $510 in fines and fees, plus the potential of a one-year driver’s license suspension.

The Securix Mississippi partnership soon soured.

Securix Chairman Jonathan Miller of Georgia said in a sworn court declaration submitted in the federal case that he was subjected around March 2024 to a “freeze out” by members and/or employees of QJR. They stopped giving him information, Miller said.

The Department of Public Safety in August pulled the plug on the controversial ticketing program, shutting off the company’s access to the insured driver database.

In September, QJR filed its Chancery Court lawsuit against Securix LLC.

What is known about the case comes from documents in the federal court file. QJR claims the company and its members have been defamed by Miller and Securix and wants their 50-50 business partnership dissolved.

The Chancery Court case does not even show up when the parties are searched for by name.

With a case number gleaned from the federal court file, a search of chancery records shows only that the case is under seal.

Normally, when a case is under seal, the docket would still be available. A docket lists all records and proceedings in a case. While sealed records are listed and described, they can’t be viewed.

“There is no court file,” attorney Laird said in asking the Supreme Court to review Judge Harris’ decision to leave the file sealed. “There is no docket sheet. There is absolutely no access on the part of the public or press to their public court file in this case.”

Judge closes file without public notice

All Mississippi court files are presumed open unless they are closed with notice and a hearing under guidelines established in the 1990 case Gannett River States Publishing Co. vs. Hand.

“It appears that the judge ignored what has been settled law in Mississippi since 1990,” said retired Jackson attorney Leonard Van Slyke, who represented Gannett in the case and still advises the media.

He added, “Since that time, there have not been many efforts to close a courtroom or a court file because the rules are pretty clear as to when that can be done. It is obvious from the rules that this would be a rare occurrence.”

A court file can be closed only if a party in the case requesting closure can show an “overriding interest” that would be prejudiced by publicity.

The Supreme Court said in 1990 that the public is entitled to at least 24 hours’ notice — on the court docket — before a judge considers closure. As a representative of the public, the media has a right to a hearing before a court file or proceeding is closed.

At the hearing, the judge must consider the least restrictive closure possible and reasonable alternatives. The judge also must make findings that explain why alternatives to closure were rejected.

The court wrote in Gannett vs. Hand:

“A transcript of the closure hearing should be made public and if a petition for extraordinary relief concerning a closure order is filed in this Court, it should be accompanied by the transcript, the court’s findings of fact and conclusions of law, and the evidence adduced at the hearing upon which the judge bases the findings and conclusions.”

Because Judge Harris held no hearing, the high court will have a scant record on which to base its review. Without a court record, Laird pointed out in his filing, the public can have no confidence the judge made a sound decision.

Kevin Goldberg, an attorney who serves as vice president and First Amendment expert at the nonpartisan, nonprofit Freedom Forum, said the First Amendment guarantees the public access to courts.

In the Securix case, he said, a private business was doing work normally performed by a police department or other public agency, and residents could be snared into legal proceedings when they received tickets and public funds were involved.

“These are not private people in a small town, going about their business,” Goldberg said. “These people’s business is the public’s business . . . I think that means they need to accept that they’re going to be scrutinized all the time, including when they voluntarily make a decision to go to court.”

This article was produced in partnership between the Sun Herald and Mississippi Today.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling. appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article maintains a largely factual and investigative tone, focusing on government transparency, judicial procedure, and public access to court records. It critiques the secrecy upheld by a judge in a politically sensitive case involving private companies executing public functions, highlighting concerns about accountability and public interest. The framing leans slightly toward advocating for open government and media rights, values often associated with center-left perspectives. However, it stops short of overt ideological framing or partisan language, striving to report the facts and legal context while underscoring the public’s right to scrutiny.

Mississippi Today

Why Andy Gipson is running for governor

Republican Andy Gipson, the first candidate to publicly announce a run for Mississippi governor in 2027, outlines his five-plank platform. No. 1 is fighting crime, which Gipson says is rising in what were once quiet rural areas, because “If people don’t feel safe, nothing else matters.” He also offers a brief sampling of his baritone crooning from his just-released two studio albums.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Why Andy Gipson is running for governor appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious

Superintendent Errick Greene wanted to be very clear with the roughly 50 parents who attended Thursday night’s community listening session: Jackson Public Schools already has a policy banning students from using cellphones at school.

But the leadership of Mississippi’s third-largest school district has decided that a new approach is in order, citing a series of incidents in recent years involving students using their cellphones to bully others, organize fights or text their parents inaccurate information about violence happening at or near their school.

“To be clear, it’s not the majority of our scholars, but I can’t look at a class and know who’s gonna be bullying today, who’s gonna be scheduling a meetup to cut up today,” Greene said toward the end of the hour-long meeting held at the JPS board room. “I can’t look at a group of scholars and say, ‘OK, yeah, you’re the one, let me take your phone, the rest of you can keep it.’”

Under the rewritten policy, students who take their phone out of their backpacks during the instructional day will lose it for five days for the first infraction, 10 days for the second and 45 days for the third. Currently, the longest the school will hold a phone is 10 days.

The Jackson school board is expected to consider the new policy at its meeting next week and the district hopes to implement the change when the new school year starts later this month, said Sherwin Johnson, the district’s communications director.

Students also currently have the option to pay up to a $25 fine to get their phone back, but the district wants to rescind that aspect of the policy.

“We’ve discovered that’s not equitable,” said Larrisa Harris, the JPS general counsel. “Not everybody has the resources to come and pay the fine.”

Support for the new policy among the parents who spoke at the listening session varied, but all had questions. How will students access the internet on their laptops if the WiFi is spotty at their school and they need to use their cellphone hotspot? If students are required to keep their phones in their backpacks during lunch, how will teachers prevent stealing? How will JPS enforce the ban on using cellphones on the bus?

One mother said she watches her daughter’s location while she rides the bus to Jim Hill High School so she knows her daughter made it safely.

“If they can’t have it on the bus, who’s gonna enforce that?” she said. “I’m just gonna be real, the bus driver got to drive.”

A common theme among parents was anxiety at the prospect of losing direct contact with their kids in the event of an emergency. A Pew Research survey found that most adults, regardless of political affiliation, support cellphone bans in middle and high school classes. But those who don’t say it’s because their child can use their phone during emergencies.

“If something happened, will we get an automatic alert to notify us? Because a lot of the time we see things on social media first,” said Ashley McIntyre, a mother of three JPS students. She attended the meeting with her eldest daughter, Aaliyah, who recently graduated from Powell Middle School.

Though JPS does have an alert system for parents, McIntyre said she didn’t know if it existed. She cited a bomb threat at Powell last year that she found out about because Aaliyah texted her, not through a school alert.

“We didn’t know what was going on, and she texted me, ‘Mom, I’m scared,’ so I went up there,” McIntyre said. “So that puts us on edge.”

Aaliyah said she uses her phone to text her mom and watch TikTok, but she feels like her classmates use their phones to be popular or to fit in. When a fight happens, she said many students pull out their phones to record instead of trying to get an adult who can stop it. Then the videos end up on Instagram pages dedicated to posting fights in JPS.

“Once the principal found out about the fight pages, they came around looking inside our videos and camera rolls,” she said. “It happened to me last year. They thought I had a fight on my phone.”

Toward the end of the meeting, Laketia Marshall-Thomas, the assistant superintendent for high schools, took the mic to respond to one parent who said she was concerned that older students would not come to school if they knew their phone could be taken.

“What we have seen is, it’s the older students—” Marshall-Thomas began.

“They are the problem,” someone from the audience chimed in.

“We’re not saying they cannot have them,” she continued. “We know that they have after school activities and they need to communicate with their moms … but we have had major, major issues with cellphones and issues that have even resulted in criminal outcomes for our scholars, but most importantly, our students … have experienced a lot of learning loss.”

While the district leadership did not go into detail about the criminal incidents, several pointed to instances where students have texted their parents inaccurate information, such as an unsubstantiated rumor there was a gun during a fight at Callaway High School or that a shooting outside Whitten Middle School occurred on school property.

“Having phones actually creates far more chaos than they help anyone,” Greene said.

While cellphones have been banned to varying degrees in U.S. schools for decades, youth mental health concerns have renewed interest in more widespread bans across the country. Cellphone and social media usage among school-aged kids is linked to negative mental health outcomes and instances of cyberbullying, research shows.

At least 11 states restrict or ban cellphone use in schools. After Mississippi’s youth mental health task force recommended that all school districts implement policies that limited cellphone and social media usage in classrooms, a bill that would’ve required school boards to create cellphone policies died during the legislative session. Still, several Mississippi school districts have passed their own policies, including Marshall County and Madison County.

Another concern about the ban was a belief among a couple of speakers at the meeting that cellphones can help parents hold the district accountable for misdeeds it may want to hide.

“I just saw a video today. It was not in JPS, but it was a child being yelled at by the teacher and had he not recorded it, his momma would have never known that this sweet lady that they go to church with is degrading her child like that,” one mother said.

Statements like these prompted responses from teachers and other parents who urged the skeptical attendees to be more trusting or to make sure the district has updated contact information for them in case school officials need to reach parents during an emergency.

“I think we have to trust the people watching over our children,” said one of the few fathers who spoke. “When I grew up, what the teacher said was gold.”

One teacher asked the audience, “Will you trust us?”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post ‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a balanced report on Jackson Public Schools’ proposed stricter cellphone policy without taking a clear ideological stance. It fairly conveys the perspectives of school officials emphasizing discipline and safety, alongside parental concerns about communication and emergency access. The tone remains neutral, focusing on factual details such as policy changes, reasons behind them, and community reactions. While it includes some skepticism from parents and responses from district staff, the language does not endorse or oppose either side. Overall, the coverage adheres to neutral, factual reporting by presenting multiple viewpoints without editorializing.

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Learning loss after Helene in Western NC school districts

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed1 day ago

Bread sold at Walmart, Kroger stores in TN, KY recalled over undeclared tree nut

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Turns out, Medicaid was for us

-

Local News7 days ago

“Gulfport Rising” vision introduced to Gulfport School District which includes plan for on-site Football Field!

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

The Bayeux Tapestry will be displayed in the UK for the first time in nearly 1,000 years

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Leawood changes street tree ordinance, launches sidewalk repair program

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Arkansas Department of Education creates searchable child care provider database

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

With brand new members, Louisiana board votes to oust local lead public defenders