Mississippi Today

Brett Favre says the welfare agency didn’t help satisfy his volleyball pledge, but Aaron Rodgers, Jimmy Buffett and others did

Brett Favre says the welfare agency didn't help satisfy his volleyball pledge, but Aaron Rodgers, Jimmy Buffett and others did

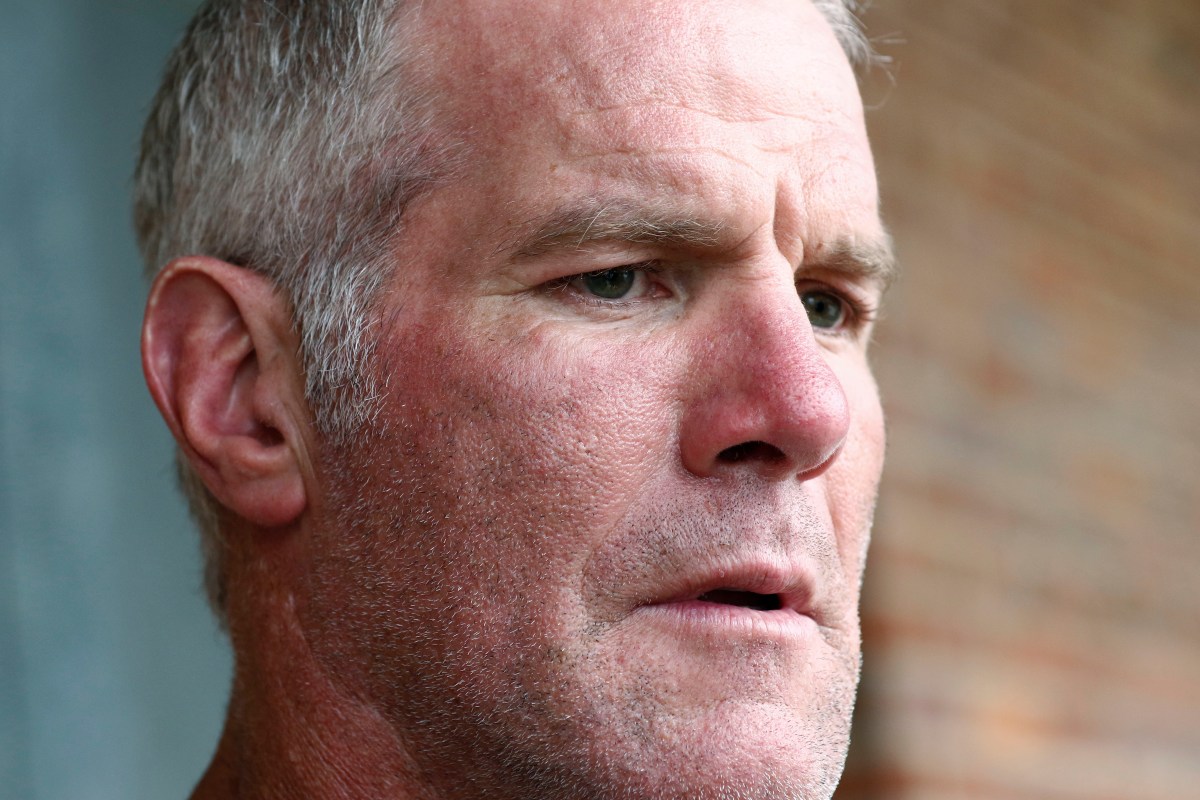

NFL legend Brett Favre says Mississippi's welfare department didn't help satisfy his pledge to fund a new volleyball stadium at University of Southern Mississippi.

But current Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers, a charity started by Margaritaville-songwriter Jimmy Buffett, and former Gov. Phil Bryant's political action committee did.

Favre has made national news in recent years for tapping his home state's welfare agency to raise funds for the stadium, but an email Mississippi Today recently obtained shows he also raised at least $180,000 for the facility from at least four charities. These are organizations that claim to increase economic, educational or workforce opportunities for families in need.

One of the key allegations against Favre in Mississippi's welfare scandal is that he personally benefited from a scheme to divert federal funds intended to help poor Mississippians to build a volleyball stadium at his alma mater.

Mississippi Department of Human Services, which is suing Favre and dozens of others to recoup the misspent funds, draws this conclusion because, they allege, Favre personally committed funds to the project, so any welfare money used to offset that obligation was a financial benefit to Favre.

The athlete, who also directly received $1.1 million in welfare funds, did personally agree to fundraise or donate just over $1.4 million, according to a never-before-published donor agreement introduced in court this month. The document was signed by Favre, his wife, and University of Southern Mississippi Athletic Foundation President Leigh Breal.

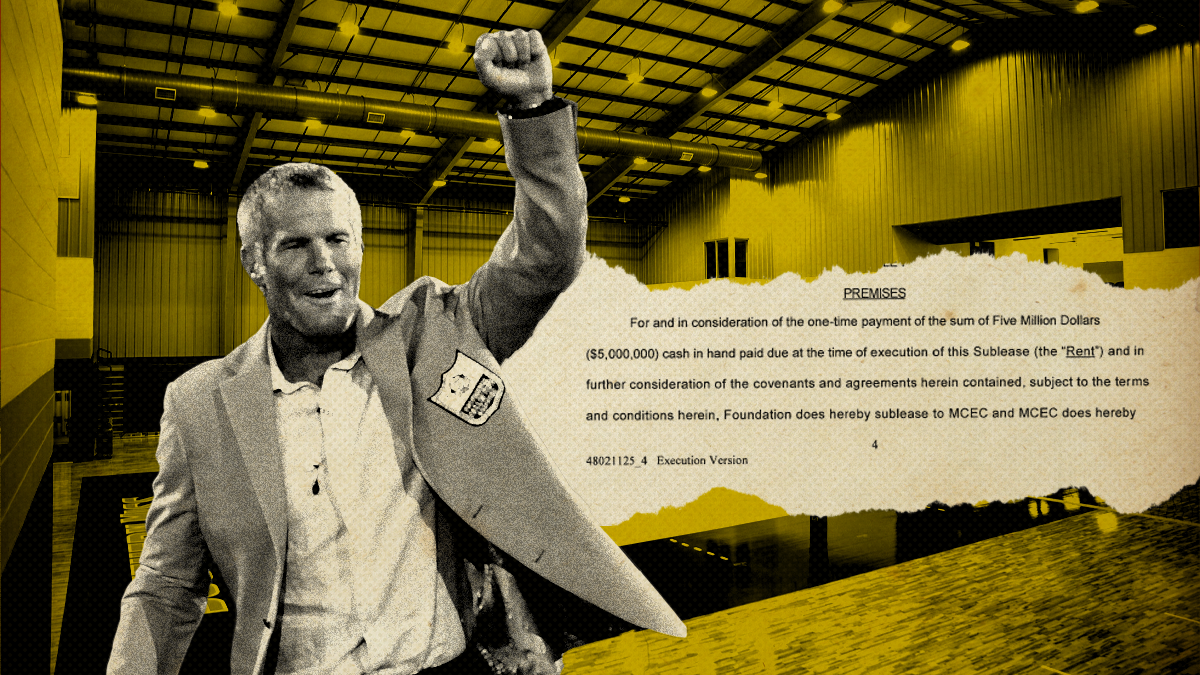

But this guarantee came months after Mississippi Department of Human Services and one of the agency's subgrantees, nonprofit Mississippi Community Education Center, had already crafted a lease agreement allowing them to funnel $5 million in federal welfare funds to the project.

In Favre's latest reply to MDHS in early April, his attorneys accuse MDHS of using legal fallacies in its civil charges against Favre.

“MDHS's theory would effectively place no limits on UFTA (Uniform Voidable Transactions Act) liability—anyone could be sued who could in any way be deemed to have reaped some undefined benefit from a transfer,” Favre's latest motion reads. “That of course is not the law in Mississippi or anywhere else.”

Since Mississippi Today first uncovered in February of 2020 that officials used welfare money to build the volleyball stadium, the entities involved have not made public a full accounting of who paid for the roughly $8 million facility, which would show who contributed to the project following Favre's commitment so he didn't personally have to.

An email recently obtained by Mississippi Today reveals publicly for the first time that, at least by the time initial arrests were made, the following individuals had made contributions towards Favre's pledge:

- American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation Inc. (6/22/18): $100,000

- Imagine Mississippi Political Action Committee (6/4/18): $2,500

- Anonymous Donor (7/30/18): $150,000

- SFC Charitable Foundation (7/10/18): $33,378

- Brett Favre (8/16/18): $50,000

- Steel Dynamics Foundation (7/9/19): $25,000

- Aaron Rodgers (10/10/19): $10,000

- Howard Deneroff (1/7/20): $500

- Jimmy A. Payne Foundation (1/13/20): $22,000

- Matt Helms (1/24/20): $360,000

Favre attached this email to his most recent court filing, but redacted the donors' names. Mississippi Today retrieved an unredacted copy, which University of Southern Mississippi should have produced to the news organization in response to a public records request last year, but did not.

The list does not implicate Rodgers, Buffett, or any other private donor in the welfare scheme. But the email serves as a key piece of evidence in Favre's defense.

The gifts cited total just over $650,000. Documents reflecting the total amount Favre personally contributed towards the project have not been made public, but his lawyer Eric Herschmann told conservative sports podcaster Jason Whitlock in a February interview that Favre donated over a million dollars of his own money to the facility. Also, The Athletic first reported that from 2018 to 2020, the same years Favre had an obligation to fund the volleyball construction, his charity Favre 4 Hope donated nearly $133,000 to USM Athletic Foundation.

In addition to the $5 million in welfare funds that went towards the facility, Nancy New, founder of the nonprofit in charge of spending welfare funds, alleged that former Gov. Bryant directed her to make $1.1 million in payments to Favre to help Favre raise funds for the stadium — an allegation Bryant has denied to the press.

But a spokesperson for the athlete recently confirmed that Favre did not use that money on the facility.

“Brett fulfilled his only obligation to USM. No funds he received from MCEC went towards the wellness center. Brett both solicited donations and often asked individuals or groups to send money to USM instead of paying him for services he provided,” a spokesperson for Favre said in a statement last week.

While a complete and reliable breakdown of the funds used to construct the facility has not been made public, outside counsel for the athletic foundation recently confirmed in an email requested by Favre's wife Deanna Favre that the Favres “satisfied the obligations of their Donor Agreement by raising or paying the Foundation in excess of the pledged amount of at least $1,406,747.55 for the Volleyball Wellness Center.”

“This includes cash donations given directly by Brett and Deanna Favre and other amounts contributed at the request of Brett and Deanna Favre,” Ridgeland-based attorney Scott Jones wrote in the Mar. 23, 2023 email to Favre's attorneys.

University of Southern Mississippi has refused to answer several questions from Mississippi Today about the volleyball project, citing litigation.

Favre began fundraising for the new volleyball stadium at USM, where his daughter played the sport, in 2017 – no one argues that. What's in dispute, and belabored in lengthy court motions back and forth, is whether Favre promised to come up with the funding for construction at the outset of the project.

Favre argues in his motion to dismiss the civil suit against him that the $5 million paid in 2017 couldn't have satisfied his $1.4 million guarantee in 2018 since the payment came before the pledge. MDHS alleges that Favre made a “handshake deal” near the inception in 2017, which is the only reason the university proceeded with the project, meaning he was on the hook for the funding the entire time.

By mid-2017, Favre had supposedly contributed $150,000 towards the volleyball project, according to an April 2017 email from Morrison to then-USM Athletic Director Jon Gilbert. After struggling to secure many more big donors, Gilbert involved nonprofit founder Nancy New, who had already entered at least one lease agreement with USM for the purpose of using grant money to make building renovations on campus – a purchase that has yet to be scrutinized.

“Brett and Deanna have agreed to help with fundraising for the facility,” Gilbert wrote in a July 16, 2017, email to New. “We currently have $1.2 million in hand from a variety of people that have committed to the project … I will find out what Brett's schedule is Tuesday and coordinate a time he can stop by that works for everyone.”

In the days and weeks following, Favre and New discussed by text the challenges in using federal grant funds for the volleyball stadium, since federal law prohibits spending of these dollars on brick-and-mortar construction projects. Favre suggested the nonprofit hire and pay him for marketing services – which are allowed under the federal rules – and that way he could pass the money to the athletic foundation.

“Will the public perception be that I became a spokesperson for various state funded shelters,schools,homes etc….. And was compensated with state money? Or can we keep this confidential,” Favre texted New in a never-before-published text first introduced into court last month.

New responded that only she, her son Zach New and former Mississippi Department of Human Services director John Davis would have information about the payment – a product of the secrecy shrouding the welfare program.

“So if we keep confidential where money came from as well as amount I think this is gonna work,” Favre wrote.

The nonprofit eventually made two $2.5 million payments through a lease agreement with USM Athletic Foundation in November and December of 2017. For this, Zach New pleaded guilty to state charges of defrauding the government. To make the lease appear legit, the nonprofit said it would occupy classrooms inside the stadium, where it would conduct programming for underprivileged people. Later that December, the nonprofit also made the first $500,000 payment directly to Favre under an agreement that he would cut a radio ad for their anti-poverty program.

In the following months, Favre learned that the construction bids had come in much higher than expected, and that USM Athletic Foundation wouldn't be able to begin building the facility until they could guarantee more funding was coming.

In April of 2018, an email stated that Favre's original gift of $500,000 towards the volleyball stadium would be reduced to $250,000 after he instructed the university to transfer half to the construction of a beach volleyball arena. (His daughter had moved from the indoor team to the beach team).

In order for work to begin, Favre signed the $1.4 million donor agreement, ensuring that he'd raise or cover the rest of the cost, on May 2, 2018.

About a week later on May 10, New texted Favre, “I am making some progress on our money needs. What amount out of the whole loan that you signed would be most helpful right now? John and I may have a plan!!”

This text appears to show that Favre and New had planned for the nonprofit to contribute towards his guarantee.

On May 17, New texted Favre, “Good news. I have a little money for the ‘project' – $500,000! Do you want me to send to the Athletic Dept. Or to your foundation.”

New sent the payment in the following weeks to Favre's for-profit company Favre Enterprises, Inc., according to the State Auditor's Office.

The text suggests that they both understood the payment to Favre – paid under what was essentially a sponsorship agreement – was ultimately for the purpose of supporting construction at USM.

“While $1,100,000 was paid based on a contract for public appearances, and Favre did record a radio advertisement, the payment was intended, as requested by Bryant, to help Favre raise funds for construction of the Volleyball Facility,” reads New's October filing in the civil case.

Through his counsel, Bryant has denied the allegation to Mississippi Today. At the point this payment was made, Favre had not yet cut the radio ad.

“Favre knew that this was a sham designed to allow MDHS to cover Favre's commitment to fund construction of the volleyball facility,” MDHS alleges in its amended complaint.

Despite their plans, Favre didn't use the money for the alleged purpose he received it, according to his spokesperson's statement.

Also in June of 2018, Favre secured donations for the facility from American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation Inc. and Bryant's PAC Imagine Mississippi Political Action Committee.

Bryant was still governor when Imagine Mississippi PAC donated $2,500 to the volleyball project in June of 2018. Bryant started the PAC by closing his campaign-finance account and transferring the bulk of the $1.05 million he had left over to the new organization in 2017 shortly after winning his second term. The PAC's stated goal is to support conservative candidates and officials. It spent about $220,000 in 2017, $216,000 in 2018, $307,000 in 2019 and $23,000 in 2020. It did not file an annual report for 2021 or 2022 or a notice of termination, according to what is available on the Secretary of State's Office website.

American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation Inc., which donated $100,000 towards the volleyball stadium, is a nonprofit focused on supporting programs in academic achievement, healthy youth development, economic opportunity, such as job training, and community resilience, including food, housing and daycare.

A spokesperson for the foundation told Mississippi Today that Favre played in its golf tournament for several years, drawing large crowds and helping fundraising efforts for its nonprofit partners. “For his participation, we made charitable contributions to a few select organizations of his choice, including the University of Southern Mississippi. Supporting colleges and universities, including programming that impacts students, aligns to the mission of the American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation.”

The spokesperson did not respond to follow up questions about what programming the foundation thought its gift was supporting.

In July of 2018, Singing For Change Charitable Foundation — a charity founded by Pascagoula-native and USM alum Jimmy Buffett with the slogan, “Turning good vibes into good deeds” — gave $33,378 for the facility. Its website says it gives grants to small, grassroots nonprofits across the country that help people “get back on their feet, back into homes, back to work, find meaningful jobs, become better educated, and thrive according to their definition.” One dollar for every concert ticket Buffett sells on tour goes towards his foundation.

“Our contribution on behalf of student wellness at USM was made in good faith to the University's foundation,” a spokesperson for SFC Charitable Foundation said in a statement to Mississippi Today. “… When any nonprofit goes astray and mismanages funds, it's a sad day for those of us in the sector but especially distressing and financially stressful for local organizations handling the fallout. As Jimmy's tour resumes this spring, we will to continue to support people living on the margins across the U.S.”

An anonymous donor also contributed $150,000 towards the volleyball stadium that month, according to the Morrison email, and Favre himself donated $50,000 the next month.

Despite personally receiving $1.1 million from the nonprofit, Favre continued in the following months and years to lobby welfare officials, other government officials and current Gov. Tate Reeves in an attempt to secure more public funds to satisfy his obligation.

But this never happened: “Zero public funds went towards satisfying this voluntary pledge,” the spokesperson for Favre confirmed for the first time to Mississippi Today recently.

It's unclear how Favre may have used the $1.1 million he received from MCEC, which he has since repaid to the state. When he spoke to his associates about his debt in the project, the number varied from $1.1 million or $1.2 million in March of 2019 to $1.8 million in September of 2019.

By July of 2019, Davis had been ousted for suspected fraud and Favre was becoming worried.

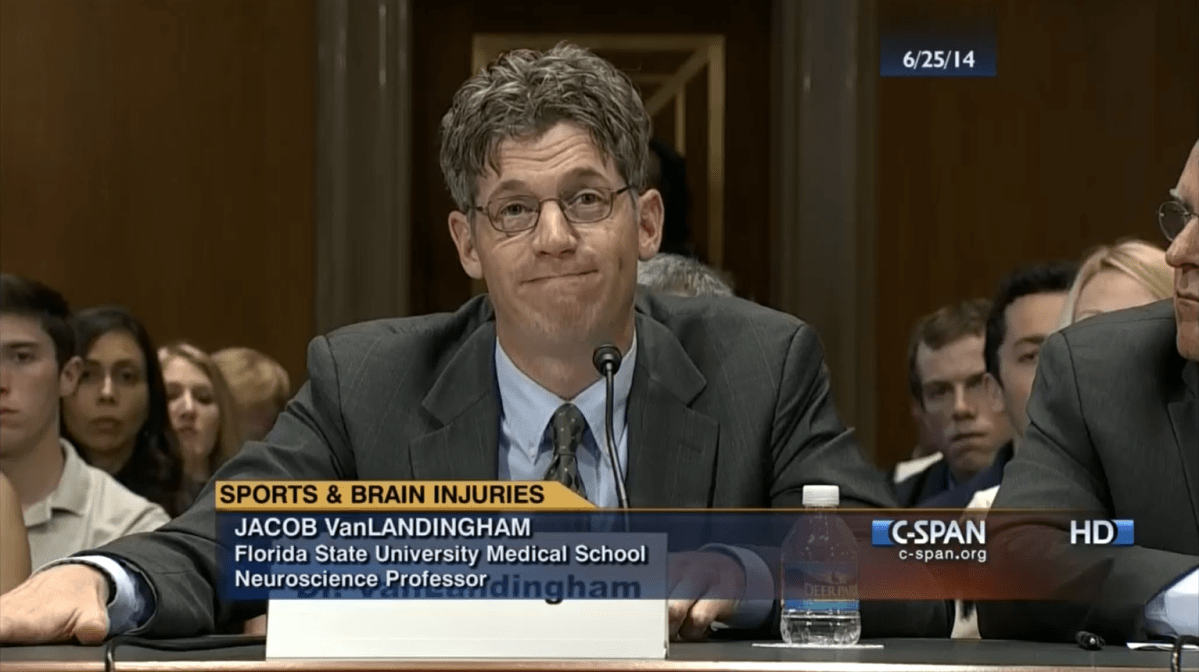

“Nancy has been awesome to me and has paid 4.5 million for a 7 million dollar facility. And she said it was all gonna be taken care of until this morning,” Favre wrote to his business associate, Jake Vanlandingham, founder of a pharmaceutical startup company called Prevacus, on July 16, 2019. This text was first published by Mississippi Today in its investigative series “The Backchannel.”

(MDHS also alleges that Favre participated in the funneling of $1.7 million in welfare money to Prevacus, to which New has pleaded guilty criminally, and that Favre is liable. In response, Favre's attorneys argue, “All Favre is alleged to have done with respect to Prevacus is to have introduced VanLandingham to New … This is insufficient to state a claim that Favre agreed to join a conspiracy … if this conduct was sufficient to join a conspiracy, then MDHS could also add as co-conspirators Southern Miss Athletic Director Jon Gilbert for his role in introducing New to Favre and attending the meeting.”)

“Suddenly she said I don't think I can do anymore,” Favre wrote to Vanlandingham, referring to New, according to “The Backchannel” texts. “So now I am looking at a big pay out.”

The same month, Steel Dynamics Foundation donated $25,000 towards Favre's volleyball pledge. Steel Dynamics Foundation is the foundation associated with Steel Dynamics Inc., a Fort Wayne, Indiana-based company that has manufacturing sites in Mississippi and recently received $247 million in tax incentives from the state. The foundation's website says its goal is to improve the quality of life and local economies in the communities where its employees work.

By September of 2019, Favre's debt had apparently grown. “I have more shit going on not to mention a very likely 1.8 million note coming due that I thought was covered,” Favre texted Vanlandingham.

That month, Favre secured a meeting with Bryant and the new welfare director, Christopher Freeze, who replaced Davis. They discussed pushing additional grant funds to the volleyball project. After the meeting, Bryant encouraged Favre by text that “We are going to get there. … But we have to follow the law.”

Freeze told Mississippi Today he rejected the proposal and there's been no evidence that any additional welfare money went to the project after this point.

The next month, Aaron Rodgers – the quarterback who replaced Favre at the Green Bay Packers, prompting a memorable feud in sports pop culture history – donated $10,000 to the facility, according to the Morrison email. Favre had also talked to Vanlandingham in 2019 about asking for Rodgers' support with the pharmaceutical venture. Rodgers' agent did not return emails or a call from Mississippi Today.

By early 2020, Favre was desperately trying to come up with the rest of the funding. According to the Morrison email, he then secured $500 from Howard Deneroff, executive producer of Westwood One Sports, an NFL broadcaster. Favre had asked Deneroff to donate in exchange for a sit-down interview on the network. Favre also collected $22,000 from the Jimmy A. Payne Foundation, the foundation of a USM alum and businessman, and $350,000 from Matt Helms, owner of a sports memorabilia store in south Mississippi.

But it wasn't enough. Favre even attempted to involve the Mississippi Community College Board, incoming Gov. Tate Reeves and the Legislature.

Bryant texted then-USM President Rodney Bennett about Favre's insistence.

“The bottom line is he personally guaranteed the project, and on his word and handshake we proceeded,” Bennett texted Bryant on Jan. 27, 2020, shortly after the outgoing governor left office. “It's time for him to pay up – it really is just that simple.”

MDHS uses this text to substantiate its allegation that Favre committed the funds before the welfare payment, since the athletic foundation proceeded with the project by hiring architects to start drafting renderings of the building in July of 2017.

All of this together, MDHS alleges, “support the reasonable inference that Favre personally committed to guarantee the volleyball facility's construction at the outset of the project.”

Favre's attorneys push back: “MDHS takes this text message completely out of context—it clearly related to efforts by Favre to raise funds to meet his 2018 written commitment,” Favre's recent reply states. “MDHS takes a giant and unsupported leap of faith in claiming that the text message related to some different, earlier commitment.”

On the day of the initial arrests in February of 2020, Morrison, the associate athletic director, sent Favre the email describing “the following gifts that have been applied towards your commitment to the Volleyball Facility.”

Asked about the timing of the email, the Favre spokesperson said, “it is purely coincidental.”

The indictment, which was made public that day, had named Prevacus and its affiliate PreSolMD, alleging that the News had embezzled welfare funds from their nonprofit to invest in the companies.

About a week later, Vanlandingham texted Favre, saying he wasn't sure if one of their potential investors was going to follow through with his contribution “given this MS embezzlement shit.”

Vanlandingham asked the athlete to make another $50,000 donation so PreSolMD could begin developing what it called a “pregame cream” that it promised could prevent concussions.

“…I would but up to my eyeballs in vball debt,” Favre responded.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On Confederate Memorial Day, an honest annotation of the Mississippi Declaration of Secession

Today, Mississippi officially recognizes Confederate Memorial Day as the anchor of Gov. Tate Reeves-proclaimed Confederate Heritage Month.

Mississippi is one of just four states to still officially recognize the state holiday, which has been granted under gubernatorial proclamations from the past five governors. Notably, one cannot find Reeves' proclamation on his social media accounts; instead, you'd have to venture over to the Facebook page of Confederate States president Jefferson Davis' home if you want to read it, as first reported by the Mississippi Free Press.

The actual language of the Confederate Heritage Month proclamation appears benign at first glance. It opens with a reference to the start of the American Civil War in 1861 and follows with an acknowledgment of Confederate Memorial Day in Mississippi (more on that to come).

But the final paragraph, when examined with a critical eye, offers a reason for pause and concern. It reads:

“WHEREAS, as we honor all who lost their lives in this war, it is important for all Americans to reflect upon our nation's past, to gain insight from our mistakes and successes, and to come to a full understanding that the lessons learned yesterday and today will carry us through tomorrow if we carefully and earnestly strive to understand and appreciate our heritage and our opportunities which lie before us.”

Gov. Tate Reeves' 2024 Confederate Heritage Month Proclamation

The “if” in that passage is doing a lot of work. We can only learn from the past IF we embrace “our heritage?” That line then begs the question, “Whose heritage, exactly?”

The answer is obvious and makes an earnest reflection of the sins of the Civil War necessary. Despite the lofty verbiage of “insight” and “lessons”, the proclamation is a prop upon which the “heritage” of the Confederacy is elevated — a heritage defined by the institution of slavery.

This Confederate Memorial Day provides us an opportunity to take a deep dive into that heritage by carefully dissecting the document that most clearly outlines and defends it.

LISTEN: A Reading of the Mississippi Declaration of Secession

The Declaration of Secession was the result of a convention of the Mississippi Legislature in January of 1861. The convention adopted a formal Ordinance of Secession written by former Congressman Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar. While the ordinance served an official purpose, the declaration laid out the grievances Mississippi's ruling class held against the federal government under the leadership of President-elect Abraham Lincoln.

Below are a few annotated excerpts from the Mississippi Declaration of Secession.

The convention really couldn't be any more straightforward with the title and opening graf of their declaration. There is little to no ambiguity about the intent of this document, which is to say, “we are seceeding and this is why.”

If there is any doubt, simply toss the title into the thesaurus machine and see what you get…

“An Assertion of the Direct Causes Which Create and Excuse the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union“

Don't think there is much mystery there.

And there it is.

Despite the “states' rights” rhetoric of the Lost Cause myth, the convention makes it undoubtedly evident that slavery is the prominent reason for secession (just like they promised to do in the previous passage).

It offers a clear and concise answer to the question, “States' rights to do what?”

Read that passage again in your best Ron Burgundy voice. “It's science.”

But in all seriousness, one can't escape the blinding racism of this passage. Nor should one ignore how damaging the perpetuity of this unscientific, unrealistic understanding of the Black race and the Black body has been in the century-and-a-half since.

These lines are in reference to the federal government's attempts to block the expansion of slavery into new territories as the United States grew.

The Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 prohibited slavery in territories formed from the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30′ parallel.

The convention doubles down on the notion that secession is not only needed to preserve the institution of slavery, but quelch any attempts to deny its existence in emerging territories

Throughout much of the convention's list of grievances, the word “it” is used as a place-holder for the “hostility to this institution” that is mentioned in the previous excerpt. Or, to put it another way, “it” is the abolitionist movement.

Again, the racism is unavoidably clear. To the convention, advocacy for social and political equality for Black Americans is akin to promoting insurrection.

What comes after is a line that probably looks all too familiar to anyone who follows the ebbs and flows of grievance politics. The convention paints the press and schools as enlisted agents against them and their cause – the echoes of which are still heard today in regards to policies directed at systemic racism or the preservation of rights for the LGBTQ+ community. It's not a new addition to the playbook, and politicians who invoke this language are merely channeling their secessionist forefathers.

You have to appreciate the tone deaf irony of this bit. It's not the 435,000-plus enslaved Mississippians who are subject to degradation, but rather the wealthy, white ruling class.

This line also helps dispel the myth of the “compassionate slaveowner,” as it clearly indicates how slave-owning Mississippians viewed the enslaved — as a calculated asset in their ledgers, as a dollar figure, as potential lost property.

To top it off, the convention elevates its cause — the preservation of slavery — to a higher status than the causes for the American Revolution.

There is one thing the Declaration of Secession makes abundantly clear: slavery — the preservation and expansion of — is the prominent reason Mississippi and 10 other states seceded to form the Confederacy.

Reeves could very easily end the practice of recognizing April as Confederate Heritage Month. It's only made possible through a proclamation of the governor. All he has to do is say “no.”

But even if Reeves remains stubborn, the legislative branch wields enormous power, too. Mississippi's state holidays are codified, and lawmakers have the power to divorce Mississippi from a century-old practice of honoring Confederates and their cause. They can pass legislation ending Confederate Memorial Day on the last Monday in April. They can sever Robert E. Lee from the annual celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. on the third Monday of January. And they can let Memorial Day exist on its own as a federal holiday without doubly venerating Jefferson Davis on the same day.

For those keeping score, that's three Confederate-themed state holidays in Mississippi.

These holidays are rooted in the Jim Crow era. They stand side-by-side with laws and policies meant to deprive Black Mississippians of their economic and civic vitality. Reeves and lawmakers could choose to start down a path of rectification — remedying some of the ills of policies designed to keep certain Mississippians disenfranchised and destitute.

But for now, the holidays — and the reasons for them — remain. Slavery and the subjugation of Black people is the bedrock of Confederate “heritage.”

The origins of Confederate Memorial Day in Mississippi trace back to 1906, a time of Southern Redemption and the reemergence of the Ku Klux Klan.

Ignorance cannot and should no longer be an excuse — certainly not in 2024.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1945

April 29, 1945

The memoir by Richard Wright about his upbringing in Roxie, Mississippi, “Black Boy,” became the top-selling book in the U.S.

Wrighyt described Roxie as “swarming with rats, cats, dogs, fortune tellers, cripples, blind men, whores, salesmen, rent collectors, and children.”

In his home, he looked to his mother: “My mother's suffering grew into a symbol in my mind, gathering to itself all the poverty, the ignorance, the helplessness; the painful, baffling, hunger-ridden days and hours; the restless moving, the futile seeking, the uncertainty, the fear, the dread; the meaningless pain and the endless suffering. Her life set the emotional tone of my life.”

When he was alone, he wrote, “I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all.”

Reading became his refuge.

“Whenever my environment had failed to support or nourish me, I had clutched at books,” he wrote. “Reading was like a drug, a dope. The novels created moods in which I lived for days.”

In the end, he discovered that “if you possess enough courage to speak out what you are, you will find you are not alone.” He was the first Black author to see his work sold through the Book-of-a-Month Club.

Wright's novel, “Native Son,” told the story of Bigger Thomas, a 20-year-old Black man whose bleak life leads him to kill. Through the book, he sought to expose the racism he saw: “I was guided by but one criterion: to tell the truth as I saw it and felt it. I swore to myself that if I ever wrote another book, no one would weep over it; that it would be so hard and deep that they would have to face it without the consolation of tears.”

The novel, which sold more than 250,000 copies in its first three weeks, was turned into a play on Broadway, directed by Orson Welles. He became friends with other writers, including Ralph Ellison in Harlem and Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus in Paris. His works played a role in changing white Americans' views on race.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Podcast: The contentious final days of the 2024 legislative session

Mississippi Today's Adam Ganucheau, Bobby Harrison and Geoff Pender break down the final negotiations of the 2024 legislative session's three major issues: Medicaid expansion, education funding, and retirement system reform.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=353661

-

Local News4 days ago

Sister of Mississippi man who died after police pulled him from car rejects lawsuit settlement

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

At Lake High School in Scott County, the Un-Team will never be forgotten

-

Mississippi Today1 day ago

On this day in 1951

-

Mississippi News2 days ago

One injured in Mississippi officer-involved shooting after chase

-

Mississippi News7 days ago

Cicadas expected to takeover north Mississippi counties soon

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Viewers make allegations against Hatley teacher, school district releases statement – Home – WCBI TV

-

Mississippi News Video5 days ago

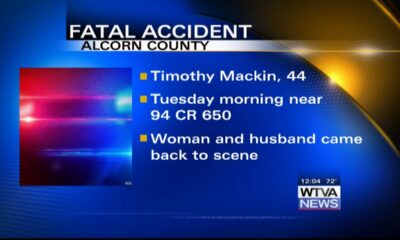

Vehicle struck and killed man lying in the road, Alcorn County sheriff says

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Ridgeland man sentenced for molesting girl