Mississippi Today

State's lack of jail inspections a disaster in the making, lawyer says

State's lack of jail inspections a disaster in the making, lawyer says

Mississippi's failure to require inspections in jails bodes disaster, says the lawyer who oversaw jail and prison conditions for decades.

In 2017, state lawmakers stopped providing funds to the Mississippi Department of Health to carry out those inspections after a federal court stopped requiring such inspections under Gates v. Collier, the longtime lawsuit brought by state inmates.

Without those inspections, “there's no check, there's none,” said Jackson lawyer Ron Welch, who represented those inmates in Mississippi jails and prisons under the court order settling that case. “It's giving sheriffs a free pass. They can do as they wish.”

He called county supervisors, who fund the sheriffs and jails, “willfully blind” accomplices.

An investigation by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today and The New York Times shows that in addition to this lack of inspections, there is a lack of oversight. No state regulator has the authority to fine a sheriff for endangering people in custody or for failing to train the staff who operate the jail.

David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project, said this is a national problem as well. Unlike almost every other country, he said, the U.S. has “no independent oversight over what happens in prisons and jails.”

This lack of oversight contributes to the abuse of those held behind bars “that is entirely foreseeable,” he said. “Their lives are systematically devalued.”

After Mississippi stopped inspecting jails, allegations arose in 2020 that Noxubee County deputies coerced Elizabeth Layne Reed, a woman incarcerated at the jail, into having sex.

Her lawsuit said two deputies, Vance Phillips and Damon Clark, gave her a cellphone and other perks, including a sofa in her cell, so that she would have sexual encounters with them. She described the first encounters as taking place outside the jail, only to be followed by those in the interrogation room, in the evidence, even in her cell.

She said in an interview that she wanted the public to know what happened to her in the hope that others would come forward. “It made me terrified to trust anybody,” she said. “Women in jail and prison need to be protected.”

According to the lawsuit, the sheriff at the time, Terry Grassaree, knew all about his deputies' “sexual contacts and shenanigans,” but did nothing to stop them. Instead, the lawsuit alleged, the sheriff “sexted” her and demanded that she use the phone the deputies had given her to send him “a continuous stream of explicit videos, photographs and texts” while she was in jail. She also alleged that Grassaree touched her in a “sexual manner.”

The lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount.

Grassaree is charged with bribery and lying to the FBI when he denied that he requested the nude photos and videos from Reed. He has pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Juan Barnett, who chairs the Senate Corrections Committee, said he supports resumed funding for jail inspections to “help curb abuse. The more oversight, the better.”

Clay County Sheriff Eddie Scott, who serves on the executive board of the Mississippi Sheriffs' Association, said he believes most sheriffs would support the return of state-funded inspections as long as they are reasonable. “We have to fight for our budgets to keep them up,” he said. “Oversight and reports have always helped me.”

Eight of Mississippi's 82 sheriffs have jails that have been certified by the state Board on Law Enforcement Officer Standards and Training; the others haven't been.

Scott said such certification reduces the cost of insurance and gives employees guidance on the best ways to run a jail.

He hopes to one day receive certification from the American Correctional Association, he said. “Getting state accredited puts me a leg up.”

Although Mississippi recently received a record $4 billion budget surplus, Welch said there's no political will right now to aid those behind bars, despite the fact that Mississippi prides itself as being part of the Bible Belt.

“God taught us to love our neighbor,” he said. “The principle is ‘do not inflict needless pain on any person.' That's the heart of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/hosemann-holds-fundraiser-at-trumps-mar-a-lago/

Mississippi Today

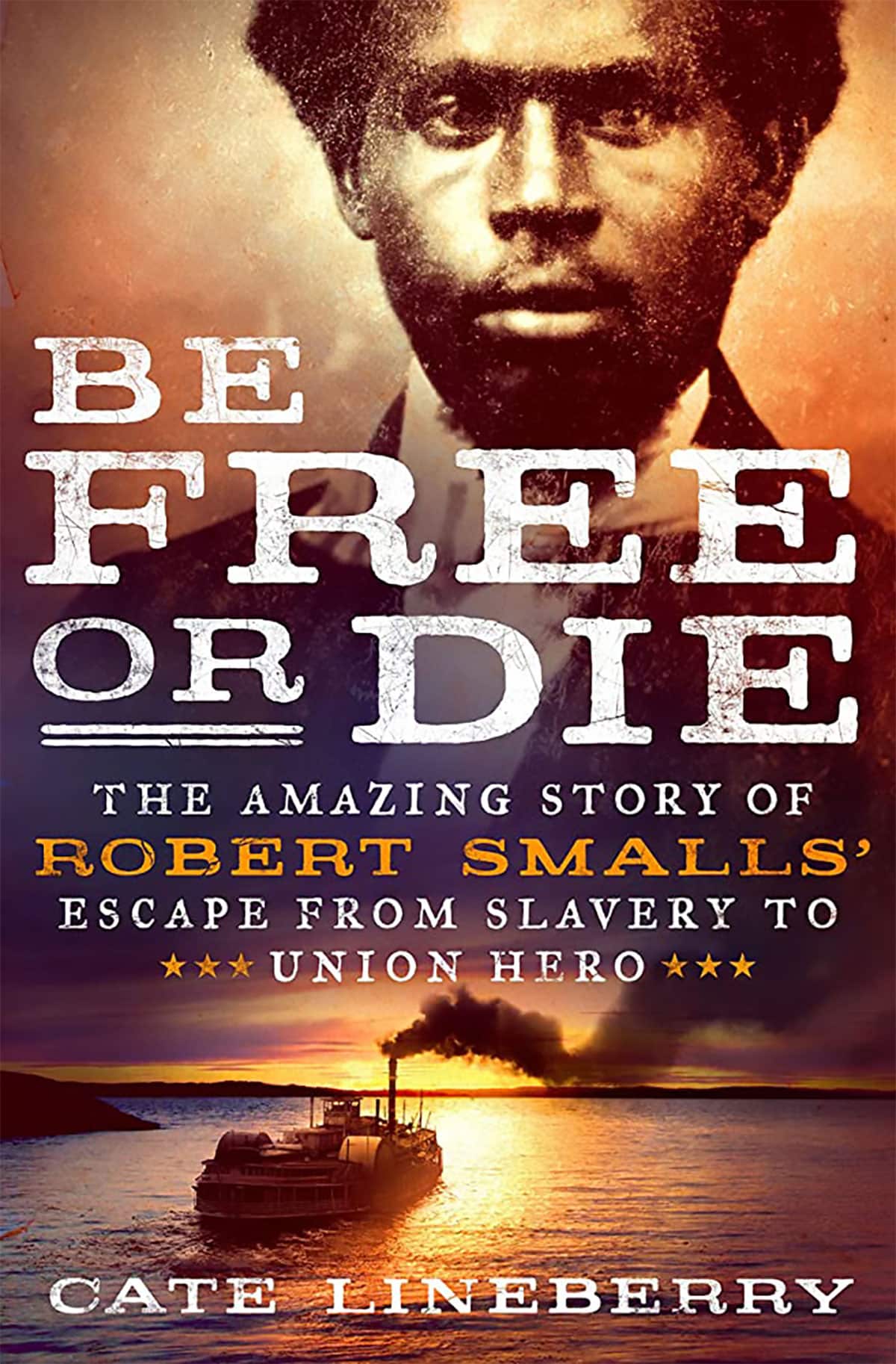

On this day in 1862

MAY 13, 1862

During the Civil War, Robert Smalls and other Black Americans who were enslaved commandeered an armed Confederate ship in Charleston. Wearing a straw hat to cover his face, Smalls disguised himself as a Confederate captain. His wife, Hannah, and members of other families joined them.

Smalls sailed safely through Confederate territory by using hand signals contained in the captain's code book, and when he and the 17 Black passengers landed in Union territory, they went from slavery to freedom. He became a hero in the North, helped convince Union leaders to permit Black soldiers to fight and became part of the war effort.

After the war ended, he returned to his native Beaufort, South Carolina, where he bought his former slaveholder's home (and allowed his widow to live there until her death). He served five terms in Congress, one of more than a dozen Black Americans to serve during Reconstruction. He also authored legislation that enabled South Carolina to have one of the nation's first free and compulsory public school systems and bought a building to use as a school for Black children.

After Reconstruction ended, however, white lawmakers passed laws to disenfranchise Black voters.

“My race needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country,” he said. “All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

He survived slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction and the beginnings of Jim Crow. He died in 1915, the same year Hollywood's racist epic film, “Birth of a Nation”, was released.

A century later, his hometown of Beaufort opened the Reconstruction Era National Monument, which features a bust of Smalls — the only known statue in the South of any of the pioneering congressmen of Reconstruction. In 2004, the U.S. named a ship after Smalls. It was the first Army ship named after a Black American. A highway into Beaufort now bears his name.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=358129

Mississippi Today

Podcast: House Minority Leader reflects on breakdown of Medicaid expansion negotiations

Rep. Robert Johnson, D-Natchez, the House minority leader, talks with Mississippi Today's Bobby Harrison and Taylor Vance on how efforts to expand Medicaid broke down during the chaotic final days of the 2024 legislative session. He hopes those efforts are revived in the 2025 session.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=357470

Mississippi Today

Lawmakers move to limit jail detentions during civil commitment

This article was produced for ProPublica's Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Mississippi lawmakers have overhauled the state's civil commitment laws after Mississippi Today and ProPublica reported that hundreds of people in the state are jailed without criminal charges every year as they wait for court-ordered mental health treatment.

Right now, anyone going through the civil commitment process can be jailed if county officials decide they have no other place to hold them. House Bill 1640, which Gov. Tate Reeves signed Wednesday, would limit the practice. It says people can be jailed as they go through the civil commitment process only if they are “actively violent” and for a maximum of 48 hours. It requires the mental health professional who recommends commitment to document why less-restrictive treatment is not an option. And before paperwork can be filed to initiate the commitment process, a staffer with a local community mental health center must assess the person's condition.

Supporters described the law, which goes into effect July 1, as a step forward in limiting jail detentions. Those praising it included county officials who handle commitments, associations representing sheriffs and county supervisors, and the state Department of Mental Health.

“This new process puts the person first,” said Adam Moore, a spokesperson for the Department of Mental Health, which provides training, along with some funding and services related to the commitment process. “It connects someone in need of mental health services with a mental health professional as the first step in the process, before the chancery court or law enforcement becomes involved.”

But some officials involved in the commitment process said that unless the state expands the number of treatment beds, the effect of the legislation will be limited. “Just because you've got a diversion program doesn't mean you have anywhere to divert them to,” said Jamie Aultman, who handles commitments as chancery clerk in Lamar County, just west of Hattiesburg.

Although every state allows people to be involuntarily committed, most don't jail people during the process unless they face criminal charges, and some prohibit the practice. Even among the few states that do jail people without charges, Mississippi is unique in how regularly it does so and for how long. Under Mississippi law, people going through the commitment process can be jailed if there is “no reasonable alternative.” State psychiatric hospitals usually have a waiting list, and short-term crisis units are often full or turn people away. Officials in many counties see jail as the only place to hold people as they await publicly funded treatment.

Idaho lawmakers recently dealt with a similar issue. There, some people deemed “dangerously mentally ill” have been imprisoned for months at a time; this spring, lawmakers funded the construction of a facility to house them.

Nearly every county in Mississippi reported jailing someone going through the commitment process at least once in the year ending in June 2023, according to the state Department of Mental Health. In just 19 of the state's 82 counties, people awaiting treatment were jailed without criminal charges at least 2,000 times from 2019 to 2022, according to a review of jail dockets by Mississippi Today and ProPublica. (Those figures, which included counties that provided jail dockets identifying civil commitment bookings, include detentions for both mental illness and substance abuse; the legislation addresses only the commitment process for mental illness.)

Sheriffs have decried the practice, saying jails aren't equipped to handle people with severe mental illness. Since 2006, at least 17 people have died after being held in jail during the civil commitment process; nine were suicides.

The bill's sponsors said Mississippi Today and ProPublica's reporting prompted them to act. “The deficiencies have been outlined and they're being corrected,” said state Rep. Kevin Felsher, R-Biloxi, a co-author of the bill.

Under current law, anyone can walk into a county office and fill out an affidavit alleging that someone, often a family member, is so seriously mentally ill that they must be forced into treatment. A judge or special master issues an order directing sheriff's deputies to take the person into custody for evaluations, a court hearing and sometimes inpatient treatment. Those screenings take place after the person is in custody — and often while they are in jail.

The legislation adds several steps to the civil commitment process in order to weed out unnecessary commitments. When someone seeks to file paperwork to commit another person, a county official will direct them to the local community mental health center. There, a mental health professional will try to interview the person alleged to be mentally ill and others who are familiar with their condition. Staff can recommend commitment or other services, including intervention by mental health professionals who will travel to the patient or inpatient treatment at a crisis stabilization unit.

As a chancery clerk in northeastern Mississippi's Lee County, Bill Benson has long dealt with people seeking to file commitment affidavits.

He said first requiring a screening by a mental health professional is a good move. “I'm an accountant. I'm not going to try and make a determination” about whether someone needs to be committed, he said. He generally allows people to file commitment papers so he can “let the judge make that call.”

The bill says that if the community mental health center recommends commitment after the initial screening, someone can't be jailed while awaiting treatment unless all other options have been exhausted and a judge specifically orders the person to be jailed. The legislation also says people can be held in jail for only 24 hours unless the community mental health center requests an additional 24-hour hold and a judge agrees. Roughly two-thirds of the people jailed over four years were held longer than 48 hours, according to Mississippi Today and ProPublica's analysis.

However, the bill does not address the underlying reason that many people are jailed as they await a treatment bed. “I'm not certain there are enough beds and personnel available to take everybody,” Benson said. “I think everyone will attempt to comply, but there are going to be some instances where somebody's going to have to be housed in the jail.”

Nor does the legislation say anything about how the provisions will be enforced. House Public Health Chair Sam Creekmore, R-New Albany, the primary sponsor of the bill, said the Department of Mental Health will “police this.” He also said he hopes the law's new reporting requirements for community mental health centers will encourage county supervisors to monitor compliance.

Moore, at the Department of Mental Health, said the agency won't enforce the law, although it will educate county officials, who are responsible for housing people going through civil commitment until they are transferred to a state hospital. “We sincerely hope all stakeholders will abide by the new processes and restrictions,” Moore said. “But DMH does not have oversight over county courts or law enforcement.”

Several mental health experts and advocates for people with mental illness say the law doesn't go far enough to ban a practice that many contend is unconstitutional. For that reason, representatives of Disability Rights Mississippi have said they're planning to sue the state and several counties.

“The basic flaw remains,” said Dr. Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University and former president of the American Psychiatric Association. “There is no justification for putting someone who needs hospital-level care in jail, not even for 24 hours.”

Agnel Philip of ProPublica and Isabelle Taft, formerly of Mississippi Today, contributed reporting.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

SuperTalk FM5 days ago

Mississippi governor approves bill allowing electronic search warrants

-

228Sports7 days ago

PRC’s Bats Come Alive Late As Blue Devils Beat Picayune To Advance To 6A South State Title Series

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Strong storms late Wednesday night – Home – WCBI TV

-

Mississippi News5 days ago

Louisville names street after a former high school

-

SuperTalk FM20 hours ago

Martin Lawrence making 3 stops in Mississippi on comedy tour

-

SuperTalk FM5 days ago

$30 million RV park coming to Natchez features amphitheater, pickle ball courts, and more

-

Mississippi News5 days ago

Crews close Jackson street due to large sinkhole

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Man arrested for allegedly breaking into home, robbing owner