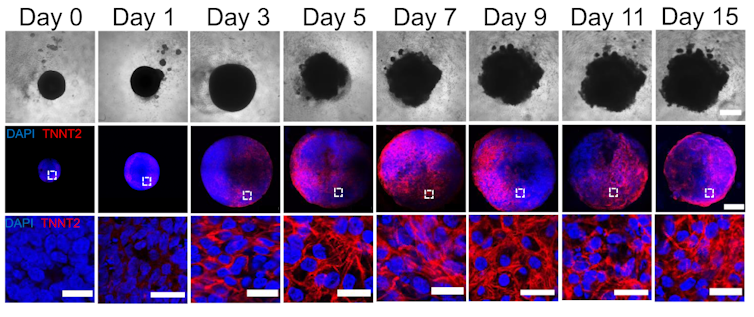

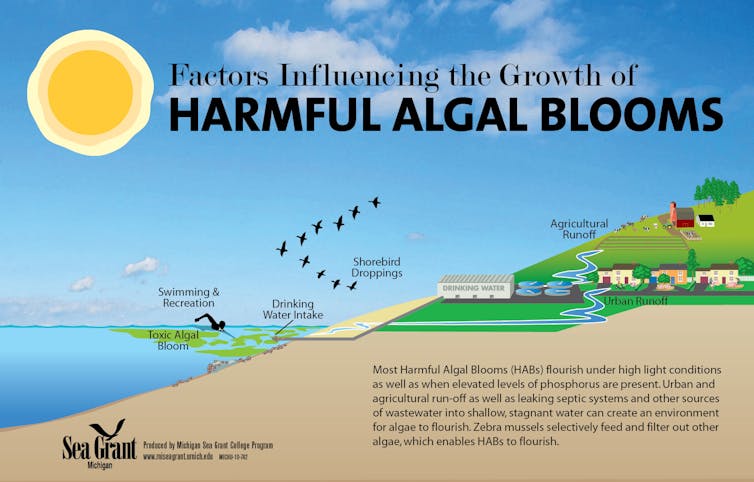

Organoids can replicate each component of the human heart, from its chambers to its veins. Yonatan R. Lewis-Israeli et al. 2021/Nature Communications, CC BY-SA

Brett Volmert, Michigan State University; Aitor Aguirre, Michigan State University, and Aleksandra Kostina, Michigan State University

How did your heart form? What triggered your first heartbeat? To this day, the mechanisms of human heart development remain elusive.

Researchers know the heart is the first organ to fully function in the growing human embryo. It begins as a simple tube that starts to pump blood by the fourth week of gestation. By the ninth week, the heart is fully formed. The heart is critical to early development because it provides essential nutrients throughout the developing fetus.

But due to its early formation, the heart is exposed for a long duration to substances a pregnant person might come into contact with, such as medications or pollutants. This may be a main reason why congenital heart disease is the most common type of birth defect in people, occurring in over 1 in 100 births worldwide.

Traditionally, scientists have used animal and cell models to study heart development and disease. However, researchers haven’t been able to produce a cure for congenital heart disease in part because these models are unable to capture the complexity of the human heart. Due to ethical limitations, using human embryos for these studies is out of the question.

To help researchers study heart development and complications in pregnancy, our team of biomedical engineers and cardiovascular scientists have spent the past several years trying to create the next best thing: mini human hearts in the lab.

Human heart organoids

Organoids are complex 3D cellular structures that replicate significant aspects of the structure and function of a specific organ in your body. While organoids are not completely synthetic, functioning organs (yet), they still possess immense power to mimic key aspects of physiology and disease in the lab.

We created our heart organoids using a type of cell called a pluripotent stem cell. Although using these cells in research used to be controversial because they were originally derived from human embryos, this is no longer a concern, as they can be produced from any adult. Pluripotent stem cells have the potential to become any type of cell in the body. This means that cells from nearly any part of your body – typically blood or skin cells – can be turned into your own stem cells to grow your own mini heart.

This figure shows the heart organoid developing over 15 days. The top row is light microscope images, while the bottom two rows show two particular proteins highlighted red and blue. Yonatan R. Lewis-Israeli et al. 2021/Nature Communications, CC BY-SA

By manipulating the ability of pluripotent stem cells to become any type of cell in the body, we guided these cells to become heart cells. The cells were able to self-assemble, replicating the main stages of human heart development during pregnancy. Our heart organoids have blood vessels and all the cell types found in the human heart, such as cardiomyocytes and pacemaker cells, which give them an edge over 2D cellular models. Furthermore, the electrophysiology and bioenergetics of these heart organoids are very similar to human embryonic hearts in ways that animal models aren’t.

Our heart organoids beat like a tiny baby’s heart, all while smaller than a grain of rice.

Pregnancy and the fetal heart

One area we’re exploring with our heart organoids is maternal and fetal cardiac health. Maternal factors such as diabetes, hypertension or even depression can increase the risk of heart disease in newborns. Studying conditions that increase the risk of congenital heart disease can prevent and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular diseases worldwide.

We can mimic these maternal environments and simulate how they influence fetal heart development with heart organoids. For example, we used heart organoids to show that diabetes, a very common condition, increases the risk of heart disease in embryos. Compared to heart organoids created in healthy conditions, mini hearts exposed to diabetic conditions developed heart abnormalities like those of human fetuses and newborns with diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Our study found that diabetes-related developmental abnormalities of the heart are likely caused by an imbalance of omega-3 fatty acids, the building blocks of cell membranes and signaling molecules. However, dietary supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids could partially restore this imbalance and prevent diabetes-induced congenital heart defects.

Drug safety during pregnancy

The drugs pregnant people take can have significant health effects on both the parent and the fetus. Medications approved for use during pregnancy are not always safe, since adequate testing is complicated. Ethical concerns limit working with biological material from people, so researchers are left with animal models that aren’t able to replicate human physiology closely enough.

Testing medications on human heart organoids allows researchers to better explore and predict potential harmful effects during pregnancy. One example is ondansetron (Zofran), a drug commonly prescribed to prevent nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. Although it has been linked with an increased risk of congenital heart disease, whether it causes the disease hasn’t been confirmed.

We showed that heart organoids exposed to ondansetron had disturbed development of ventricular cells and impaired function, similar to what’s seen in newborns exposed to ondansetron. Our findings provide data that may help update clinical guidelines on the use of the drug.

Certain medications may increase the risk of congenital heart defects.

Another example concerns the use of antidepressants during pregnancy, which is associated with an increased risk of congenital heart defects. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, the most prescribed antidepressants in pregnant people, work by increasing the availability of serotonin in the body. Serotonin is an important molecule in cardiac development. Maternal serotonin, along with antidepressants, readily pass to the embryo and alter serotonin levels in the developing heart.

In the future, we plan to expose heart organoids to antidepressants and study their effects on the incidence of congenital heart defects. The results of such research on human heart organoids may also inform recommendations for drug replacement or repurposing.

Heart organoids have the potential to help scientists more precisely study how the human heart forms and how it develops disease. In the realm of medical innovation, we believe human heart organoids grown from stem cells are the beating promise of a healthier future.

Brett Volmert, Ph.D. Candidate in Biomedical Engineering, Michigan State University; Aitor Aguirre, Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Michigan State University, and Aleksandra Kostina, Postdoctoral Researcher in Quantitative Health Sciences and Engineering, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.