Kaiser Health News

Facing Financial Ruin as Costs Soar for Elder Care

Reed Abelson, The New York Times and Jordan Rau, KFF Health News

Tue, 14 Nov 2023 10:35:00 +0000

Margaret Newcomb, 69, a retired French teacher, is desperately trying to protect her retirement savings by caring for her 82-year-old husband, who has severe dementia, at home in Seattle. She used to fear his disease-induced paranoia, but now he’s so frail and confused that he wanders away with no idea of how to find his way home. He gets lost so often that she attaches a tag to his shoelace with her phone number.

Feylyn Lewis, 35, sacrificed a promising career as a research director in England to return home to Nashville after her mother had a debilitating stroke. They ran up $15,000 in medical and credit card debt while she took on the role of caretaker.

Sheila Littleton, 30, brought her grandfather with dementia to her family home in Houston, then spent months fruitlessly trying to place him in a nursing home with Medicaid coverage. She eventually abandoned him at a psychiatric hospital to force the system to act.

“That was terrible,” she said. “I had to do it.”

Millions of families are facing such daunting life choices — and potential financial ruin — as the escalating costs of in-home care, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes devour the savings and incomes of older Americans and their relatives.

“People are exposed to the possibility of depleting almost all their wealth,” said Richard Johnson, director of the program on retirement policy at the Urban Institute.

The prospect of dying broke looms as an imminent threat for the boomer generation, which vastly expanded the middle class and looked hopefully toward a comfortable retirement on the backbone of 401(k)s and pensions. Roughly 10,000 of them will turn 65 every day until 2030, expecting to live into their 80s and 90s as the price tag for long-term care explodes, outpacing inflation and reaching a half-trillion dollars a year, according to federal researchers.

The challenges will only grow. By 2050, the population of Americans 65 and older is projected to increase by more than 50%, to 86 million, according to census estimates. The number of people 85 or older will nearly triple to 19 million.

The United States has no coherent system of long-term care, mostly a patchwork. The private market, where a minuscule portion of families buy long-term care insurance, has shriveled, reduced over years of giant rate hikes by insurers that had underestimated how much care people would actually use. Labor shortages have left families searching for workers willing to care for their elders in the home. And the cost of a spot in an assisted living facility has soared to an unaffordable level for most middle-class Americans. They have to run out of money to qualify for nursing home care paid for by the government.

For an examination of the crisis in long-term care, The New York Times and KFF Health News interviewed families across the nation as they struggled to obtain care; examined companies that provide it; and analyzed data from the federally funded Health and Retirement Study, the most authoritative national survey of older people about their long-term care needs and financial resources.

About 8 million people 65 and older reported that they had dementia or difficulty with basic daily tasks like bathing and feeding themselves — and nearly 3 million of them had no assistance at all, according to an analysis of the survey data. Most people relied on spouses, children, grandchildren, or friends.

The United States devotes a smaller share of its gross domestic product to long-term care than do most other wealthy countries, including Britain, France, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and Japan, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The United States lags its international peers in another way: It dedicates far less of its overall health spending toward long-term care.

“We just don’t value elders the way that other countries and other cultures do,” said Rachel Werner, executive director of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. “We don’t have a financing and insurance system for long-term care,” she said. “There isn’t the political will to spend that much money.”

Despite medical advances that have added years to the average life span and allowed people to survive decades more after getting cancer or suffering from heart disease or strokes, federal long-term care for older people has not fundamentally changed in the decades since President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare and Medicaid into law in 1965. From 1960 to 2021, the number of Americans age 85 and older increased at more than six times the rate of the general population, according to census records.

Medicare, the federal health insurance program for Americans 65 and older, covers the costs of medical care, but generally pays for a home aide or a stay in a nursing home only for a limited time during a recovery from a surgery or a fall or for short-term rehabilitation.

Medicaid, the federal-state program, covers long-term care, usually in a nursing home, but only for the poor. Middle-class people must exhaust their assets to qualify, forcing them to sell much of their property and to empty their bank accounts. If they go into a nursing home, they are permitted to keep a pittance of their retirement income: $50 or less a month in a majority of states. And spouses can hold onto only a modest amount of income and assets, often leaving their children and grandchildren to shoulder some of the financial burden.

“You basically want people to destitute themselves and then you take everything else that they have,” said Gay Glenn, whose mother lived in a nursing home in Kansas until she died in October at age 96.

Her mother, Betty Mae Glenn, had to spend down her savings, paying the home more than $10,000 a month, until she qualified for Medicaid. Glenn, 61, relocated from Chicago to Topeka more than four years ago, moving into one of her mother’s two rental properties and overseeing her care and finances.

Under the state Medicaid program’s byzantine rules, she had to pay rent to her mother, and that income went toward her mother’s care. Glenn sold the family’s house just before her mother’s death in October. Her lawyer told her the estate had to pay Medicaid back about $20,000 from the proceeds.

A play she wrote about her relationship with her mother, titled “If You See Panic in My Eyes,” was read this year at a theater festival.

At any given time, skilled nursing homes house roughly 630,000 older residents whose average age is about 77, according to recent estimates. A long-term resident’s care can easily cost more than $100,000 a year without Medicaid coverage at these institutions, which are supposed to provide round-the-clock nursing coverage.

Nine in 10 people said it would be impossible or very difficult to pay that much, according to a KFF public opinion poll conducted during the pandemic.

Efforts to create a national long-term care system have repeatedly collapsed. Democrats have argued that the federal government needs to take a much stronger hand in subsidizing care. The Biden administration sought to improve wages and working conditions for paid caregivers. But a $150 billion proposal in the Build Back Better Act for in-home and community-based services under Medicaid was dropped to lower the price tag of the final legislation.

“This is an issue that’s coming to the front door of members of Congress,” said Sen. Bob Casey, a Pennsylvania Democrat and chair of the Senate Special Committee on Aging. “No matter where you’re representing — if you’re representing a blue state or red state — families are not going to settle for just having one option,” he said, referring to nursing homes funded under Medicaid. “The federal government has got to do its part, which it hasn’t.”

But leading Republicans in Congress say the federal government cannot be expected to step in more than it already does. Americans need to save for when they will inevitably need care, said Sen. Mike Braun of Indiana, the ranking Republican on the aging committee.

“So often people just think it’s just going to work out,” he said. “Too many people get to the point where they’re 65 and then say, ‘I don’t have that much there.’”

Private Companies’ Prices Have Skyrocketed

The boomer generation is jogging and cycling into retirement, equipped with hip and knee replacements that have slowed their aging. And they are loath to enter the institutional setting of a nursing home.

But they face major expenses for the in-between years: falling along a spectrum between good health and needing round-the-clock care in a nursing home.

That has led them to assisted living centers run by for-profit companies and private equity funds enjoying robust profits in this growing market. Some 850,000 people age 65 or older now live in these facilities that are largely ineligible for federal funds and run the gamut, with some providing only basics like help getting dressed and taking medication and others offering luxury amenities like day trips, gourmet meals, yoga, and spas.

The bills can be staggering.

Half of the nation’s assisted living facilities cost at least $54,000 a year, according to Genworth, a long-term care insurer. That rises substantially in many metropolitan areas with lofty real estate prices. Specialized settings, like locked memory care units for those with dementia, can cost twice as much.

Home care is costly, too. Agencies charge about $27 an hour for a home health aide, according to Genworth. Hiring someone who spends six or seven hours a day cleaning and helping an older person get out of bed or take medications can add up to $60,000 a year.

As Americans live longer, the number who develop dementia, a condition of aging, has soared, as have their needs. Five million to 7 million Americans age 65 and up have dementia, and their ranks are projected to grow to nearly 12 million by 2040. The condition robs people of their memories, mars the ability to speak and understand, and can alter their personalities.

In Seattle, Margaret and Tim Newcomb sleep on separate floors of their two-story cottage, with Margaret ever mindful that her husband, who has dementia, can hallucinate and become aggressive if medication fails to tame his symptoms.

“The anger has diminished from the early days,” she said last year.

But earlier on, she had resorted to calling the police when he acted erratically.

“He was hating me and angry, and I didn’t feel safe,” she said.

She considered memory care units, but the least expensive option cost around $8,000 a month and some could reach nearly twice that amount. The couple’s monthly income, with his pension from Seattle City Light, the utility company, and their combined Social Security, is $6,000.

Placing her husband in such a place would have gutted the $500,000 they had saved before she retired from 35 years teaching art and French at a parochial school.

“I’ll let go of everything if I have to, but it’s a very unfair system,” she said. “If you didn’t see ahead or didn’t have the right type of job that provides for you, it’s tough luck.”

In the last year, medication has quelled Tim’s anger, but his health has declined so much that he no longer poses a physical threat. Margaret said she’s reconciled to caring for him as long as she can.

“When I see him sitting out on the porch and appreciating the sun coming on his face, it’s really sweet,” she said.

The financial threat posed by dementia also weighs heavily on adult children who have become guardians of aged parents and have watched their slow, expensive declines.

Claudia Morrell, 64, of Parkville, Maryland, estimated her mother, Regine Hayes, spent more than $1 million during the eight years she needed residential care for dementia. That was possible only because her mother had two pensions, one from her husband’s military service and another from his job at an insurance company, plus savings and Social Security.

Morrell paid legal fees required as her mother’s guardian, as well as $6,000 on a special bed so her mother wouldn’t fall out and on private aides after she suffered repeated small strokes. Her mother died last December at age 87.

“I will never have those kinds of resources,” Morrell, an education consultant, said. “My children will never have those kinds of resources. We didn’t inherit enough or aren’t going to earn enough to have the quality of care she got. You certainly can’t live that way on Social Security.”

Women Bear the Burden of Care

For seven years, Annie Reid abandoned her life in Colorado to sleep in her childhood bedroom in Maryland, living out of her suitcase and caring for her mother, Frances Sampogna, who had dementia. “No one else in my family was able to do this,” she said.

“It just dawned on me, I have to actually unpack and live here,” Reid, 61, remembered thinking. “And how long? There’s no timeline on it.”

After Sampogna died at the end of September 2022, her daughter returned to Colorado and started a furniture redesign business, a craft she taught herself in her mother’s basement. Reid recently had her knee replaced, something she could not do in Maryland because her insurance didn’t cover doctors there.

“It’s amazing how much time went by,” she said. “I’m so grateful to be back in my life again.”

Studies are now calculating the toll of caregiving on children, especially women. The median lost wages for women providing intensive care for their mothers is $24,500 over two years, according to a study led by Norma Coe, an associate professor at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

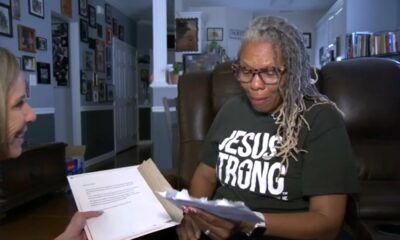

Lewis moved back from England to Nashville to care for her mother, a former nurse who had a stroke that put her in a wheelchair.

“I was thrust back into a caregiving role full time,” she said. She gave up a post as a research director for a nonprofit organization. She is also tending to her 87-year-old grandfather, ill with prostate cancer and kidney disease.

Making up for lost income seems daunting while she continues to support her mother.

But she is regaining hope: She was promoted to assistant dean for student affairs at Vanderbilt School of Nursing and was recently married. She and her husband plan to stay in the same apartment with her mother until they can save enough to move into a larger place.

Government Solutions Are Elusive

Over the years, lawmakers in Congress and government officials have sought to ease the financial burdens on individuals, but little has been achieved.

The CLASS Act, part of the Obamacare legislation of 2010, was supposed to give people the option of paying into a long-term insurance program. It was repealed two years later amid compelling evidence that it would never be economically viable.

Two years ago, another proposal, called the WISH Act, outlined a long-term care trust fund, but it never gained traction.

On the home care front, the scarcity of workers has led to a flurry of attempts to improve wages and working conditions for paid caregivers. A provision in the Build Back Better Act to provide more funding for home care under Medicaid was not included in the final Inflation Reduction Act, a less costly version of the original bill that Democrats sought to pass last year.

The labor shortages are largely attributed to low wages for difficult work. In the Medicaid program, demand has clearly outstripped supply, according to a recent analysis. While the number of home aides in the Medicaid program has increased to 1.4 million in 2019 from 840,000 in 2008, the number of aides per 100 people who qualify for home or community care has declined nearly 12%.

In April, President Joe Biden signed an executive order calling for changes to government programs that would improve conditions for workers and encourage initiatives that would relieve some of the burdens on families providing care.

Turning to Medicaid, a Shredded Safety Net

The only true safety net for many Americans is Medicaid, which represents, by far, the largest single source of funding for long-term care.

More than 4 in 5 middle-class people 65 or older who need long-term care for five years or more will eventually enroll, according to an analysis for the federal government by the Urban Institute. Almost half of upper-middle-class couples with lifetime earnings of more than $4.75 million will also end up on Medicaid.

But gaps in Medicaid coverage leave many people without care. Under federal law, the program is obliged to offer nursing home care in every state. In-home care, which is not guaranteed, is provided under state waivers, and the number of participants is limited. Many states have long waiting lists, and it can be extremely difficult to find aides willing to work at the low-paying Medicaid rate.

Qualifying for a slot in a nursing home paid by Medicaid can be formidable, with many families spending thousands of dollars on lawyers and consultants to navigate state rules. Homes may be sold or couples may contemplate divorce to become eligible.

And recipients and their spouses may still have to contribute significant sums. After Stan Markowitz, a former history professor in Baltimore with Parkinson’s disease, and his wife, Dottye Burt, 78, exhausted their savings on his two-year stay in an assisted living facility, he qualified for Medicaid and moved into a nursing home.

He was required to contribute $2,700 a month, which ate up 45% of the couple’s retirement income. Burt, who was a racial justice consultant for nonprofits, rented a modest apartment near the home, all she could afford on what was left of their income.

Markowitz died in September at age 86, easing the financial pressure on her. “I won’t be having to pay the nursing home,” she said.

Even finding a place willing to take someone can be a struggle. Harold Murray, Sheila Littleton’s grandfather, could no longer live safely in rural North Carolina because his worsening dementia led him to wander. She brought him to Houston in November 2020, then spent months trying to enroll him in the state’s Medicaid program so he could be in a locked unit at a nursing home.

She felt she was getting the runaround. Nursing home after nursing home told her there were no beds, or quibbled over when and how he would be eligible for a bed under Medicaid. In desperation, she left him at a psychiatric hospital so it would find him a spot.

“I had to refuse to take him back home,” she said. “They had no choice but to place him.”

He was finally approved for coverage in early 2022, at age 83.

A few months later, he died.

Reed Abelson is a health care reporter for The New York Times. The New York Times’ Kirsten Noyes and graphics editor Albert Sun, KFF Health News data editor Holly K. Hacker, and JoNel Aleccia, formerly of KFF Health News, contributed to this report.

US Health and Retirement Study Analysis

The New York Times-KFF Health News data analysis was based on the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative longitudinal survey of about 20,000 people age 50 and older. The analysis defined people age 65 and above as likely to need long-term care if they were assessed to have dementia, or if they reported having difficulty with two or more of six specified activities of daily living: bathing, dressing, eating, getting in and out of bed, walking across a room, and using the toilet. The Langa-Weir classification of cognitive function, a related data set, was used to identify respondents with dementia. The analysis’s definition of needing long-term care assistance is conservative and in line with the criteria most long-term care insurers use in determining whether they will pay for services.

People were described as recipients of long-term care help if they reported receiving assistance in the month before the interview for the study or if they lived in a nursing home. The analysis was developed in consultation with Norma Coe, an associate professor of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The financial toll on middle-class and upper-income people needing long-term care was examined by reviewing data that the HRS collected from 2000 to 2021 on wealthy Americans, those whose net worth at age 65 was in the 50th to 95th percentile, totaling anywhere from $171,365 to $1,827,765 in inflation-adjusted 2020 dollars. This group excludes the super-wealthy. Each individual’s wealth at age 65 was compared with their wealth just before they died to calculate the percentage of affluent people who exhausted their financial resources and the likelihood that would occur among different groups.

To calculate how many people were likely to need long-term care, how many people needing long-term care services were receiving them, and who was providing care to people receiving help, we looked at people age 65 and older of all wealth levels in the 2020-21 survey, the most recent.

The U.S. Health and Retirement Study is conducted by the University of Michigan and funded by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration.

——————————

By: Reed Abelson, The New York Times and Jordan Rau, KFF Health News

Title: Facing Financial Ruin as Costs Soar for Elder Care

Sourced From: kffhealthnews.org/news/article/dying-broke-facing-financial-ruin-as-costs-soar-for-elder-care/

Published Date: Tue, 14 Nov 2023 10:35:00 +0000

Kaiser Health News

A California Lawmaker Leans Into Her Medical Training in Fight for Health Safety Net

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — State Sen. Akilah Weber Pierson anticipates that California’s sprawling Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, may need to be dialed back after Gov. Gavin Newsom releases his latest budget, which could reflect a multibillion-dollar deficit.

Even so, the physician-turned-lawmaker, who was elected to the state Senate in November, says her priorities as chair of a budget health subcommittee include preserving coverage for the state’s most vulnerable, particularly children and people with chronic health conditions.

“We will be spending many, many hours and long nights figuring this out,” Weber Pierson said of the lead-up to the state’s June 15 deadline for lawmakers to pass a balanced budget.

With Medicaid cuts on the table in Washington and Medi-Cal running billions of dollars over budget due to rising drug prices and higher-than-anticipated costs to cover immigrants without legal status, Weber Pierson’s dual responsibilities — maintaining a balanced budget and delivering compassionate care to the state’s poorest residents — could make her instrumental in leading Democrats through this period of uncertainty.

President Donald Trump has said GOP efforts to cut federal spending will not touch Medicaid beyond “waste, fraud, and abuse.” Congressional Republicans are considering going after states such as California that extend coverage to immigrants without legal status and imposing restrictions on provider taxes. California voters in November made permanent the state’s tax on managed-care health plans to continue funding Medi-Cal.

The federal budget megabill is winding its way through Congress, where Republicans have set a target of $880 billion in spending cuts over 10 years from the House committee that oversees the Medicaid program.

Health care policy researchers say that would inevitably force the program to restrict eligibility, narrow the scope of benefits, or both. Medi-Cal covers 1 in 3 Californians, and more than half of its nearly $175 billion budget comes from the federal government.

One of a handful of practicing physicians in the state legislature, Weber Pierson is leaning heavily on her experience as a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist who treats children with reproductive birth defects — one of only two in Southern California.

Weber Pierson spoke to KFF Health News correspondent Christine Mai-Duc in Sacramento this spring. She has introduced bills to improve timely access to care for pregnant Medi-Cal patients, require developers to mitigate bias in artificial intelligence algorithms used in health care, and compel health plans to cover screenings for housing, food insecurity, and other social determinants of health.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: You’re a state senator, you practice medicine in your district, and you’re also a mom. What does that look like day to day?

A: When you grow up around someone who juggles a lot, that just kind of becomes the norm. I saw this with my mom [former state Assembly member Shirley Weber, who is now secretary of state].

I’m really happy that I’m able to continue with my clinical duties. Those in the health care profession understand how much time, energy, effort, and money we put into becoming a health care provider, and I’m still fairly early in my career. With my particular specialty, it would also be a huge void in the San Diego region for me to step back.

Q: What are the biggest threats or challenges in health care right now?

A: The immediate threats are the financial issues and our budget. A lot of people do not understand the overwhelming amount of dollars that go into our health care system from the federal government.

Another issue is access. Almost everybody in California is covered by insurance. The problem is that we have not expanded access to providers. If you have insurance but your nearest labor and delivery unit is still two hours away, what exactly have we really done for those patients?

The third thing is the social determinants of health. The fact that your life expectancy is based on the ZIP code in which you were born is absolutely criminal. Why are certain areas devoid of having supermarkets where you can go and get fresh fruits and vegetables? And then we wonder why certain people have high blood pressure and diabetes and obesity.

Q: On the federal level, there’s a lot of conversation happening around Medicaid cuts, reining in the MCO tax, and potentially dropping Affordable Care Act premium subsidies. Which is the biggest threat to California?

A: To be quite honest with you, all of those. The MCO tax was a recognition that we needed more providers, and in order to get more providers, we need to increase the Medi-Cal reimbursement rates. The fact that now it is at risk is very, very concerning. That is how we are able to care for those who are our most vulnerable in our state.

Q: If those cuts do come, what do we cut? How do we cut it?

A: We are in a position where we have to talk about it at this point. Our Medi-Cal budget, outside of what the federal government may do, is exploding. We definitely have to ensure that those who are our most vulnerable — our kids, those with chronic conditions — continue to have some sort of coverage. What will that look like?

To be quite honest with you, at this point, I don’t know.

Q: How can the state make it the least painful for Californians?

A: Sometimes the last one to the table is the first one to have to leave the table. And so I think that’s probably an approach that we will look at. What were some of the more recent things that we’ve added, and we’ve added a lot of stuff lately. How can we trim down — maybe not completely eliminate, but trim down on — some of these services to try to make them more affordable?

Q: When you say the last at the table, are you talking about the expansion of Medi-Cal coverage to Californians without legal status? Certain age groups?

A: I don’t want to get ahead of this conversation, because it is a very large conversation between not only me but also the [Senate president] pro tem, the Assembly speaker, and the governor’s office. But those conversations are being had, keeping in mind that we want to provide the best care for as many people as possible.

Q: You’re carrying a bill related to AI in health care this year. Tell me what you’re trying to address.

A: It has just exploded at a speed that I don’t know any of us were anticipating. We are trying to play catch-up, because we weren’t really at the table when all of this stuff was being rolled out.

As we advance in technology, it’s been great; we’ve extended lives. But we need to make sure that the biases that led to various discrepancies and health care outcomes are not the same biases that are inputted into that system.

Q: How does Sacramento policy impact your patients and what experience as a physician do you bring to policymaking?

A: I speak with my colleagues with actual knowledge of what’s happening with our patients, what’s happening in the clinics. My patients and my fellow providers will often come to me and say, “You guys are getting ready to do this, and this is why it’s going to be a problem.” And I’m like, “OK, that’s really good to know.”

I work at a children’s facility, and right after the election, specialty hospitals were very concerned around funding and their ability to continue to practice.

In the MCO discussion, I was hearing from providers, hospitals on the ground on a regular basis. With the executive order [on gender-affirming care for transgender youth], I have seen people that I work with concerned, because these are patients that they take care of. I’m very grateful for the opportunity to be in both worlds.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

The post A California Lawmaker Leans Into Her Medical Training in Fight for Health Safety Net appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content leans center-left due to its focus on preserving and protecting Medi-Cal, a Medicaid program serving vulnerable populations, particularly children and immigrants. It highlights concerns about federal budget cuts proposed by Republicans and emphasizes the importance of maintaining social services, healthcare access, and addressing social determinants of health. The perspective is generally supportive of expanding healthcare coverage and cautious about fiscal reductions affecting marginalized groups, which aligns with moderate Democratic and progressive viewpoints.

Kaiser Health News

Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

The Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

After narrowly passing a budget resolution this spring foreshadowing major Medicaid cuts, Republicans in Congress are having trouble agreeing on specific ways to save billions of dollars from a pool of funding that pays for the program without cutting benefits on which millions of Americans rely. Moderates resist changes they say would harm their constituents, while fiscal conservatives say they won’t vote for smaller cuts than those called for in the budget resolution. The fate of President Donald Trump’s “one big, beautiful bill” containing renewed tax cuts and boosted immigration enforcement could hang on a Medicaid deal.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration surprised those on both sides of the abortion debate by agreeing with the Biden administration that a Texas case challenging the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone should be dropped. It’s clear the administration’s request is purely technical, though, and has no bearing on whether officials plan to protect the abortion pill’s availability.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Anna Edney of Bloomberg News, Maya Goldman of Axios, and Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Anna Edney

Bloomberg News

Maya Goldman

Axios

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- Congressional Republicans are making halting progress on negotiations over government spending cuts. As hard-line House conservatives push for deeper cuts to the Medicaid program, their GOP colleagues representing districts that heavily depend on Medicaid coverage are pushing back. House Republican leaders are eying a Memorial Day deadline, and key committees are scheduled to review the legislation next week — but first, Republicans need to agree on what that legislation says.

- Trump withdrew his nomination of Janette Nesheiwat for U.S. surgeon general amid accusations she misrepresented her academic credentials and criticism from the far right. In her place, he nominated Casey Means, a physician who is an ally of HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s and a prominent advocate of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

- The pharmaceutical industry is on alert as Trump prepares to sign an executive order directing agencies to look into “most-favored-nation” pricing, a policy that would set U.S. drug prices to the lowest level paid by similar countries. The president explored that policy during his first administration, and the drug industry sued to stop it. Drugmakers are already on edge over Trump’s plan to impose tariffs on drugs and their ingredients.

- And Kennedy is scheduled to appear before the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee next week. The hearing would be the first time the secretary of Health and Human Services has appeared before the HELP Committee since his confirmation hearings — and all eyes are on the committee’s GOP chairman, Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a physician who expressed deep concerns at the time, including about Kennedy’s stances on vaccines.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and co-wrote the latest KFF Health News’ “Bill of the Month” installment, about an unexpected bill for what seemed like preventive care. If you have an outrageous, baffling, or infuriating medical bill you’d like to share with us, you can do that here.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: NPR’s “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured,” by Andrea Hsu.

Maya Goldman: STAT’s “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph.

Anna Edney: Bloomberg News’ “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare,” by Zachary R. Mider and Zeke Faux.

Sandhya Raman: The Louisiana Illuminator’s “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” by Anna Claire Vollers.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

We encourage organizations to republish our content, free of charge. Here’s what we ask:

You must credit us as the original publisher, with a hyperlink to our kffhealthnews.org site. If possible, please include the original author(s) and KFF Health News” in the byline. Please preserve the hyperlinks in the story.

It’s important to note, not everything on kffhealthnews.org is available for republishing. If a story is labeled “All Rights Reserved,” we cannot grant permission to republish that item.

Have questions? Let us know at KHNHelp@kff.org

The post Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content provides a balanced overview of current health policy issues with a slight lean towards framing Republican budget efforts and Medicaid cuts critically, emphasizing the potential negative impacts on constituents reliant on these programs. The coverage fairly presents multiple viewpoints, including fiscal conservatives and moderates within the Republican Party, but the tone suggests some skepticism towards conservative budget priorities and Trump administration policies. Overall, the focus on health care access and concerns about cuts aligns with a center-left perspective without strong partisan language or ideological bias.

Kaiser Health News

As Republicans Eye Sweeping Medicaid Cuts, Missouri Offers a Preview

CRESTWOOD, Mo. — The prospect of sweeping federal cuts to Medicaid is alarming to some Missourians who remember the last time the public medical insurance program for those with low incomes or disabilities was pressed for cash in the state.

In 2005, Missouri adopted some of the strictest eligibility standards in the nation, reduced benefits, and increased patients’ copayments for the joint federal-state program due to state budget shortfalls totaling about $2.4 billion over several prior years. More than 100,000 Missourians lost coverage as a result, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia reported that the changes led to increases in credit card borrowing and debt in third-party collections.

A woman told NPR that year that her $6.70-an-hour McDonald’s job put her over the new income limits and rendered her ineligible, even though she was supporting three children on about $300 a week. A woman receiving $865 a month in disability payments worried at a town hall meeting about not being able to raise her orphaned granddaughter as the state asked her to pay $167 a month to keep her health coverage.

Now, Missouri could lose an estimated $2 billion a year in federal funding as congressional Republicans look to cut at least $880 billion over a decade from a pool of funding that includes Medicaid programs nationwide. Medicaid and the closely related Children’s Health Insurance Program together insure roughly 79 million people — about 1 in 5 Americans.

“We’re looking at a much more significant impact with the loss of federal funds even than what 2005 was,” said Amy Blouin, president of the progressive Missouri Budget Project think tank. “We’re not going to be able to protect kids. We’re not going to be able to protect people with disabilities from some sort of impact.”

At today’s spending levels, a cut of $880 billion to Medicaid could lead to states’ losing federal funding ranging from $78 million a year in Wyoming to $13 billion a year in California, according to an analysis from KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News. State lawmakers nationwide would then be left to address the shortfalls, likely through some combination of slashing benefits or eligibility, raising taxes, or finding a different large budget item to cut, such as education spending.

Republican lawmakers are floating various proposals to cut Medicaid, including one to reduce the money the federal government sends to states to help cover adults who gained access to the program under the Affordable Care Act’s provision known as Medicaid expansion. The 2010 health care law allowed states to expand Medicaid eligibility to cover more adults with low incomes. The federal government is picking up 90% of the tab for that group. About 20 million people nationwide are now covered through that expansion.

Missouri expanded Medicaid in 2021. That has meant that a single working-age adult in Missouri can now earn up to $21,597 a year and qualify for coverage, whereas before, nondisabled adults without children couldn’t get Medicaid coverage. That portion of the program now covers over 329,000 Missourians, more than a quarter of the state’s Medicaid recipients.

For every percentage point that the federal portion of the funding for that group decreases, Missouri’s Medicaid director estimated, the state could lose $30 million to $35 million a year.

But the equation is even more complicated given that Missouri expanded access via a constitutional amendment. Voters approved the expansion in 2020 after the state’s Republican leadership resisted doing so for a decade. That means changes to Medicaid expansion in Missouri would require voters to amend the state constitution again. The same is true in South Dakota and Oklahoma.

So even if Congress attempted to narrowly target cuts to the nation’s Medicaid expansion population, Washington University in St. Louis health economist Timothy McBride said, Missouri’s expansion program would likely stay in place.

“Then you would just have to find the money elsewhere, which would be brutal in Missouri,” McBride said.

In Crestwood, a suburb of St. Louis, Sandra Smith worries her daughter’s in-home nursing care would be on the chopping block. Nearly all in-home services are an optional part of Medicaid that states are not required to include in their programs. But the services have been critical for Sandra and her 24-year-old daughter, Sarah.

Sarah Smith has been disabled for most of her life due to seizures from a rare genetic disorder called Dravet syndrome. She has been covered by Medicaid in various ways since she was 3.

She needs intensive, 24-hour care, and Medicaid pays for a nurse to come to their home 13 hours a day. Her mother serves as the overnight caregiver and covers when the nurses are sick — work Sandra Smith is not allowed to be compensated for and that doesn’t count toward the 63-year-old’s Social Security.

Having nursing help allows Sandra Smith to work as an independent podcast producer and gives her a break from being the go-to-person for providing care 24 hours a day, day after day, year after year.

“I really and truly don’t know what I would do if we lost the Medicaid home care. I have no plan whatsoever,” Sandra Smith said. “It is not sustainable for anyone to do infinite, 24-hour care without dire physical health, mental health, and financial consequences, especially as we parents get into our elder years.”

Elias Tsapelas, director of fiscal policy at the conservative Show-Me Institute, said potential changes to Medicaid programs depend on the extent of any budget cuts that Congress ultimately passes and how much time states have to respond.

A large cut implemented immediately, for example, would require state legislators to look for parts of the budget they have the discretion to cut quickly. But if states have time to absorb funding changes, he said, they would have more flexibility.

“I’m not ready to think that Congress is going to willingly put us on the path of making every state go cut their benefits for the most vulnerable,” Tsapelas said.

Missouri’s congressional delegation split along party lines over the recent budget resolution calling for deep spending cuts, with the Republicans who control six of the eight House seats and both Senate seats all voting for it.

But 76% of the public, including 55% of Republicans, say they oppose major federal funding cuts to Medicaid, according to a national KFF poll conducted April 8-15.

And Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, a Republican, has said that he does not support cutting Medicaid and posted on the social platform X that he was told by President Donald Trump that the House and Senate would not cut Medicaid benefits and that Trump won’t sign any benefit cuts.

“I hope congressional leadership will get the message,” Hawley posted. He declined to comment for this article.

U.S. House Republicans are aiming to pass a budget by Memorial Day, after many state legislatures, including Missouri’s, will have adjourned for the year.

Meanwhile, Missouri lawmakers are poised to pass a tax cut that is estimated to reduce state revenue by about $240 million in the first year.

The post As Republicans Eye Sweeping Medicaid Cuts, Missouri Offers a Preview appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content displays a center-left political bias by emphasizing the negative impacts of proposed Republican-led federal cuts to Medicaid funding. It highlights the struggles of low-income and disabled individuals who rely on Medicaid, underscores the importance of Medicaid expansion, and includes perspectives from progressive advocates concerned about the consequences of funding reductions. Although it presents some conservative viewpoints, such as those from the Show-Me Institute and mentions Republican lawmakers’ positions, the overall tone supports maintaining or expanding social welfare programs, reflecting a center-left leaning perspective.

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days agoMissouri family, two Oklahoma teens among 8 killed in Franklin County crash

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days agoMotel in Roswell shutters after underage human trafficking sting | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed3 days agoAerospace supplier, a Fortune 500 company, chooses North Carolina site | North Carolina

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed3 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed3 days agoRaleigh woman gets 'miracle' she prayed for after losing thousands in scam

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Florida News Feed2 days agoPalm Bay suspends school zone speed cameras again, this time through rest of school year

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days agoGas station employee killed, customer assaulted in Harnett Co. robbery

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

Mississippi Today5 days agoCoast protester suffers brain bleed after alleged attack by retired policeman

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago72nd Annual Reunion for those who once lived in Dunbarton, Sc

![HIGH SCHOOL SOFTBALL: East Central vs Vancleave (5/10/2025) [5A Playoffs, South State Game 2]](https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/1746971504_maxresdefault-80x80.jpg)