In the U.S., if you waive your Miranda rights, you'll be interrogated – whether you're drunk or sober.

Jacqueline R. Evans, Florida International University

Imagine it's Friday night. You're enjoying happy hour with friends after a long week. You're relaxed, having indulged in several of your preferred adult beverages. Now imagine that as you leave the bar, a police officer approaches. You're under arrest.

Flash forward to the police station. The officer takes you to a cramped room and reads you your Miranda rights: You have the right to remain silent, to an attorney, and all the rest. Let's say you waive those rights – most people do – and the officer questions you for several hours.

While under the influence, would you understand your Miranda rights and appreciate the consequences of choosing to invoke or waive them? Would the statements you made during questioning be more or less reliable than how you'd respond sober? Would a jury take what the drunken you said seriously? These are the questions that legal psychologists like me and my colleagues seek to address in our research.

Suspects get similar treatment, drunk or not

When we've surveyed police, they revealed it's common to question intoxicated suspects and that they tend to use the same interrogation techniques with drunken suspects that they normally use. Surveys of community members about their experience with interrogation confirm that questioning drunken suspects is common. In fact, sometimes police even interrogate drunken juveniles.

Of course, police in the U.S. cannot legally question anyone in custody unless that person has waived their Miranda rights and chosen to talk to the investigator. It's a common misperception that drunken people cannot legally waive their Miranda rights and that statements given while intoxicated cannot be used against them in court. But the reality is that from a legal perspective the police can Mirandize you while you're under the influence, interrogate you, and use your statements against you.

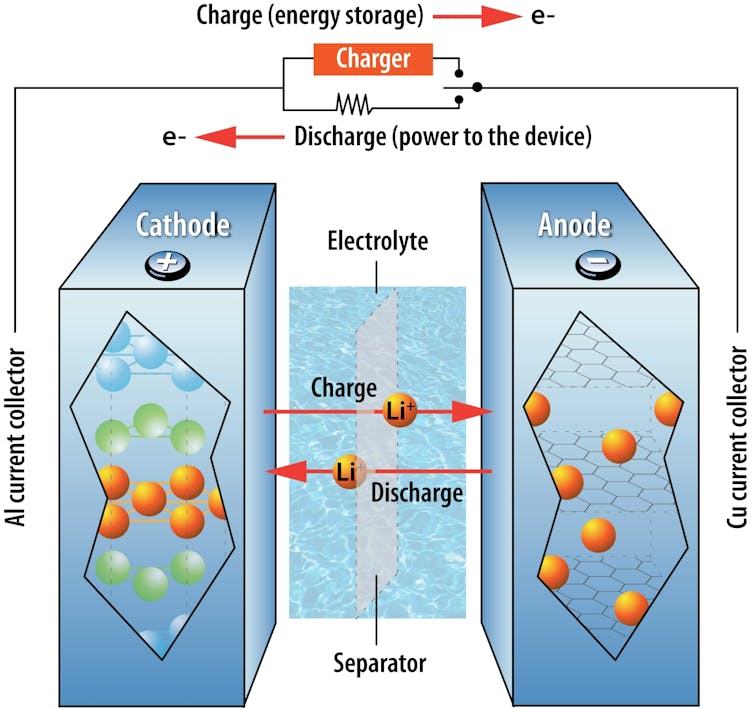

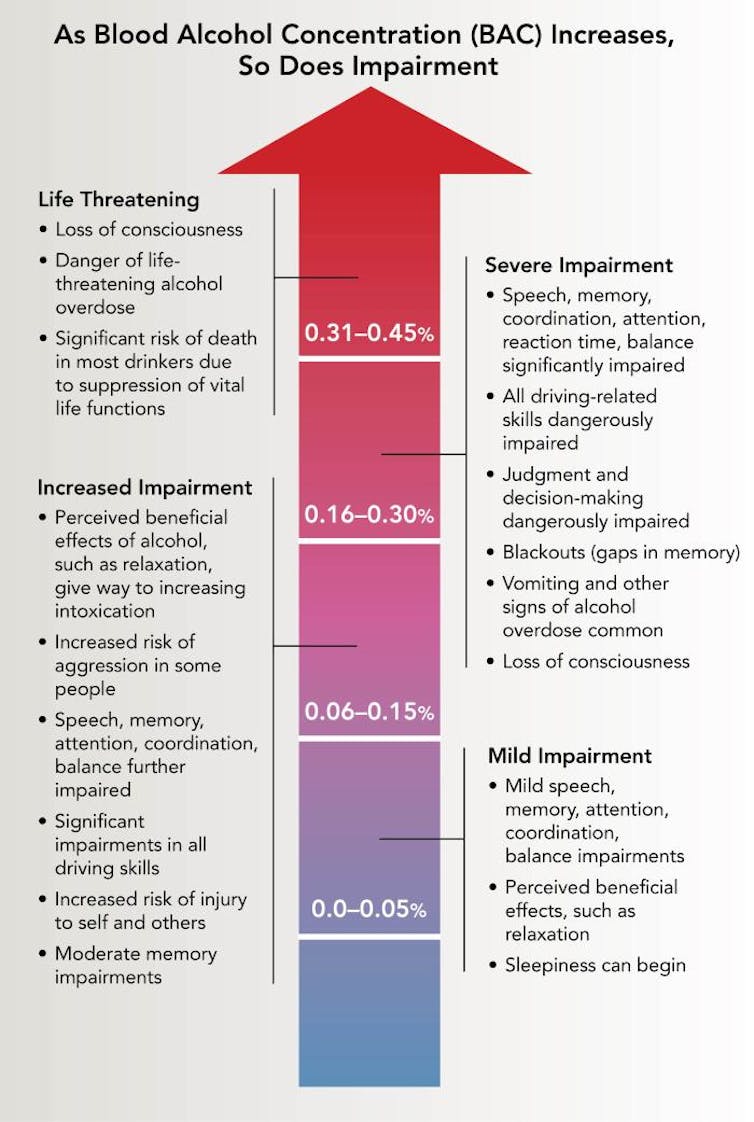

Level of impairment rises along with how much you've had to drink.

NIH National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, CC BY

Consider the case of Travis Jewell. When he was arrested for fleeing a police officer in his truck, his blood alcohol level was .29, more than three times the legal limit of .08 in the U.S. The interrogator reported Jewell was slurring words and struggling to stand. Nonetheless, the court accepted his Miranda waiver, making Jewell's statements admissible during trial.

While Miranda waivers from intoxicated people may be legally valid, research from my lab suggests that when compared with sober individuals, someone under the influence of drugs or alcohol – even at low levels of intoxication – may be less able to comprehend their rights.

Testing how drunken ‘suspects' behave

Critically, researchers know almost nothing about how intoxicated people behave during interrogation.

To address this need, my colleagues and I brought university student volunteers into the lab, where we have safeguards in place to minimize health risks. We had some of our participants drink enough vodka to reach a breath alcohol level of .08%, a level consistent with the legal driving limit in the U.S.

Then we set the participants up to be guilty or innocent of cheating, and interrogated each of them about potential academic misconduct. We were interested in whether, impaired or sober, they said anything incriminating or suspicious during questioning.

About two-thirds of sober participants said something suggestive of guilt, while even more intoxicated participants did. The difference in suspicious statements between the groups was not statistically significant, but our findings do indicate that intoxicated people – just like the rest of the public – are at a high risk of self-incrimination. And remember, in our study, half of the participants were innocent of the infraction they were being questioned about.

Standard legal advice is to keep your mouth shut until you are able to meet with a lawyer.

Suspicious remarks can have immediate consequences during interrogation. When a suspect says something suggestive of guilt, it tends to increase an interrogator's belief that they're guilty. When interrogators have a stronger belief in guilt, they then tend to be more accusatory, an approach associated with false confessions.

Intoxicated suspects – guilty or innocent – are very likely to make a guilt-suggestive statement, which in turn is likely to invite more coercive interrogation approaches. This could potentially explain our recent real-world findings in Sweden that police interrogators used more confrontational techniques with intoxicated suspects than with sober suspects.

On a positive note, our work has also shown that potential jurors seem to recognize that intoxication may lead to less reliable statements during interrogation. They tend to give less weight to a confession from an intoxicated suspect than from a sober suspect. While that may sound reassuring, should you find yourself in that cramped interrogation room, sober or intoxicated, exercise your rights and ask for an attorney.

Jacqueline R. Evans, Associate Professor of Psychology, Florida International University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.