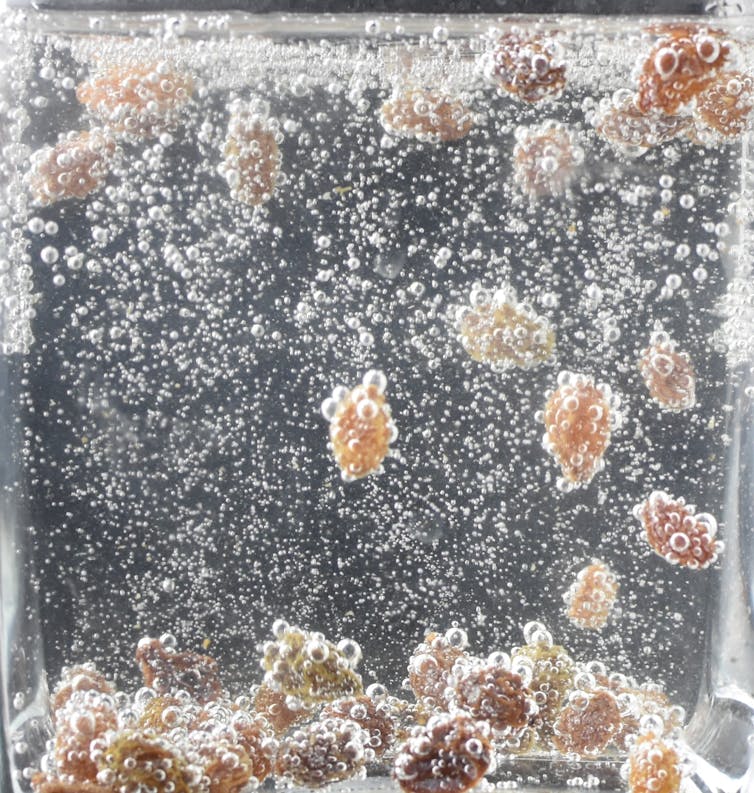

Surface bubble growth can lift objects upward against gravity.

Saverio Spagnolie

Saverio Eric Spagnolie, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Scientific discovery doesn't always require a high-tech laboratory or a hefty budget. Many people have a first-rate lab right in their own homes – their kitchen.

The kitchen offers plenty of opportunities to view and explore what physicists call soft matter and complex fluids. Everyday phenomena, such as Cheerios clustering in milk or rings left when drops of coffee evaporate, have led to discoveries at the intersection of physics and chemistry and other tasteful collaborations between food scientists and physicists.

Two students, Sam Christianson and Carsen Grote, and I published a new study in Nature Communications in May 2024 that dives into another kitchen observation. We studied how objects can levitate in carbonated fluids, a phenomenon that's whimsically referred to as dancing raisins.

The study explored how objects like raisins can rhythmically move up and down in carbonated fluids for several minutes, even up to an hour.

An accompanying Twitter thread about our research went viral, amassing over half a million views in just two days. Why did this particular experiment catch the imaginations of so many?

Bubbling physics

Sparkling water and other carbonated beverages fizz with bubbles because they contain more gas than the fluid can support – they're “supersaturated” with gas. When you open a bottle of champagne or a soft drink, the fluid pressure drops and CO₂ molecules begin to make their escape to the surrounding air.

Bubbles do not usually form spontaneously in a fluid. A fluid is composed of molecules that like to stick together, so molecules at the fluid boundary are a bit unhappy. This results in surface tension, a force which seeks to reduce the surface area. Since bubbles add surface area, surface tension and fluid pressure normally squeeze any forming bubbles right back out of existence.

But rough patches on a container's surface, like the etchings in some champagne glasses, can protect new bubbles from the crushing effects of surface tension, offering them a chance to form and grow.

Bubbles also form inside the microscopic, tubelike cloth fibers left behind after wiping a glass with a towel. The bubbles grow steadily on these tubes and, once they're big enough, detach and float upward, carrying gas out of the container.

But as many champagne enthusiasts who put fruits in their glasses know, surface etchings and little cloth fibers aren't the only places where bubbles can form. Adding a small object like a raisin or a peanut to a sparkling drink also enables bubble growth. These immersed objects act as alluring new surfaces for opportunistic molecules like CO₂ to accumulate and form bubbles.

And once enough bubbles have grown on the object, a levitation act may be performed. Together, the bubbles can lift the object up to the surface of the liquid. Once at the surface, the bubbles pop, dropping the object back down. The process then begins again, in a periodic vertical dancing motion.

Dancing raisins

Raisins are particularly good dancers. It takes only a few seconds for enough bubbles to form on a raisin's wrinkly surface before it starts to rise upward – bubbles have a harder time forming on smoother surfaces. When dropped into just-opened sparkling water, a raisin can dance a vigorous tango for 20 minutes, and then a slower waltz for another hour or so.

We found that rotation, or spinning, was critically important for coaxing large objects to dance. Bubbles that cling to the bottom of an object can keep it aloft even after the top bubbles pop. But if the object starts to spin even a little bit, the bubbles underneath make the body spin even faster, which results in even more bubbles popping at the surface. And the sooner those bubbles are removed, the sooner the object can get back to its vertical dancing.

Small objects like raisins do not rotate as much as larger objects, but instead they do the twist, rapidly wobbling back and forth.

Modeling the bubbly flamenco

In the paper, we developed a mathematical model to predict how many trips to the surface we would expect an object like a raisin to make. In one experiment, we placed a 3D-printed sphere that acted as a model raisin in a glass of just-opened sparkling water. The sphere traveled from the bottom of the container to the top over 750 times in one hour.

The model incorporated the rate of bubble growth as well as the object's shape, size and surface roughness. It also took into account how quickly the fluid loses carbonation based on the container's geometry, and especially the flow created by all that bubbly activity.

Bubble-coated raisins ‘dance' to the surface and plummet once their lifting agents have popped.

Saverio Spagnolie

The mathematical model helped us determine which forces influence the object's dancing the most. For example, the fluid drag on the object turned out to be relatively unimportant, but the ratio of the object's surface area to its volume was critical.

Looking to the future, the model also provides a way to determine some hard to measure quantities using more easily measured ones. For example, just by observing an object's dancing frequency, we can learn a lot about its surface at the microscopic level without having to see those details directly.

Different dances in different theaters

These results aren't just interesting for carbonated beverage lovers, though. Supersaturated fluids exist in nature, too – magma is one example.

As magma in a volcano rises closer to the Earth's surface, it rapidly depressurizes, and dissolved gases from inside the volcano make a dash for the exit, just like the CO₂ in carbonated water. These escaping gases can form into large, high-pressure bubbles and emerge with such force that a volcanic eruption ensues.

The particulate matter in magma may not dance in the same way raisins do in soda water, but tiny objects in the magma may affect how these explosive events play out.

The past decades have also seen an eruption of a different kind – thousands of scientific studies devoted to active matter in fluids. These studies look at things such as swimming microorganisms and the insides of our fluid-filled cells.

Most of these active systems do not exist in water but instead in more complicated biological fluids that contain the energy necessary to produce activity. Microorganisms absorb nutrients from the fluid around them to continue swimming. Molecular motors carry cargo along a superhighway in our cells by pulling nearby energy in the form of ATP from the environment.

Studying these systems can help scientists learn more about how the cells and bacteria in the human body function, and how life on this planet has evolved to its current state.

Meanwhile, a fluid itself can behave strangely because of a diverse molecular composition and bodies moving around inside it. Many new studies have addressed the behavior of microorganisms in such fluids as mucus, for instance, which behaves like both a viscous fluid and an elastic gel. Scientists still have much to learn about these highly complex systems.

While raisins in soda water seem fairly simple when compared with microorganisms swimming through biological fluids, they offer an accessible way to study generic features in those more challenging settings. In both cases, bodies extract energy from their complex fluid environment while also affecting it, and fascinating behaviors ensue.

New insights about the physical world, from geophysics to biology, will continue to emerge from tabletop-scale experiments – and perhaps from right in the kitchen.

Saverio Eric Spagnolie, Professor of Mathematics, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.