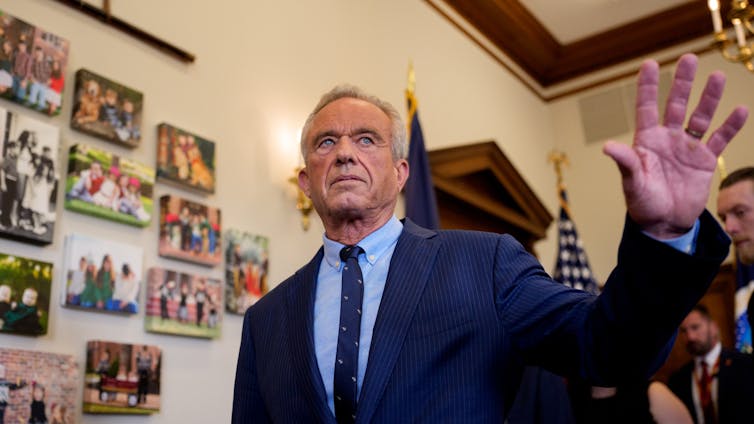

Andrew HarnikGetty Images

Jake Scott, Stanford University

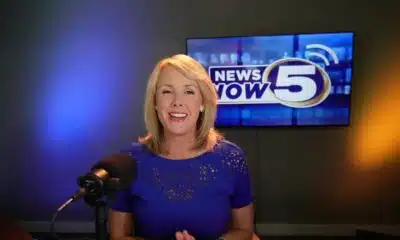

In the four months since he began serving as secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has made many public statements about vaccines that have cast doubt on their safety and on the objectivity of long-standing processes established to evaluate them.

Many of these statements are factually incorrect. For example, in a newscast aired on June 12, 2025, Kennedy told Fox News viewers that 97% of federal vaccine advisers are on the take. In the same interview, he also claimed that children receive 92 mandatory shots. He has also widely claimed that only COVID-19 vaccines, not other vaccines in use by both children and adults, were ever tested against placebos and that “nobody has any idea” how safe routine immunizations are.

As an infectious disease physician who curates an open database of hundreds of controlled vaccine trials involving over 6 million participants, I am intimately familiar with the decades of research on vaccine safety. I believe it is important to correct the record – especially because these statements come from the official who now oversees the agencies charged with protecting Americans’ health.

Do children really receive 92 mandatory shots?

In 1986, the childhood vaccine schedule contained about 11 doses protecting against seven diseases. Today, it includes roughly 50 injections covering 16 diseases. State school entry laws typically require 30 to 32 shots across 10 to 12 diseases. No state mandates COVID-19 vaccination. Where Kennedy’s “92 mandatory shots” figure comes from is unclear, but the actual number is significantly lower.

From a safety standpoint, the more important question is whether today’s schedule with additional vaccines might be too taxing for children’s immune systems. It isn’t, because as vaccine technology improved over the past several decades, the number of antigens in each vaccine dose is much lower than before.

Antigens are the molecules in vaccines that trigger a response from the immune system, training it to identify the specific pathogen. Some vaccines contain a minute amount of aluminum salt that serves as an adjuvant – a helper ingredient that improves the quality and staying power of the immune response, so each dose can protect with less antigen.

Those 11 doses in 1986 delivered more than 3,000 antigens and 1.5 milligrams of aluminum over 18 years. Today’s complete schedule delivers roughly 165 antigens – which is a 95% reduction – and 5-6 milligrams of aluminum in the same time frame. A single smallpox inoculation in 1900 exposed a child to more antigens than today’s complete series.

Underwood Archives via Getty Images

Since 1986, the United States has introduced vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis A and B, chickenpox, pneumococcal disease, rotavirus and human papillomavirus. Each addition represents a life-saving advance.

The incidence of Haemophilus influenzae type b, a bacterial infection that can cause pneumonia, meningitis and other severe diseases, has dropped by 99% in infants. Pediatric hepatitis infections are down more than 90%, and chickenpox hospitalizations are down about 90%. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that vaccinating children born from 1994 to 2023 will avert 508 million illnesses and 1,129,000 premature deaths.

Placebo testing for vaccines

Kennedy has asserted that only COVID-19 vaccines have undergone rigorous safety trials in which they were tested against placebos. This is categorically wrong.

Of the 378 controlled trials in our database, 195 compared volunteers’ response to a vaccine with their response to a placebo. Of those, 159 gave volunteers only a salt water solution or another inert substance. Another 36 gave them just the adjuvant without any viral or bacterial material, as a way to see whether there were side effects from the antigen itself or the injection. Every routine childhood vaccine antigen appears in at least one such study.

The 1954 Salk polio trial, one of the largest clinical trials in medical history, enrolled more than 600,000 children and tested the vaccine by comparing it with a salt water control. Similar trials, which used a substance that has no biological effect as a control, were used to test Haemophilus influenzae type b, pneumococcal, rotavirus, influenza and HPV vaccines.

Once an effective vaccine exists, ethics boards require new versions be compared against that licensed standard because withholding proven protection from children would be unethical.

How unknown is the safety of widely used vaccines?

Kennedy has insisted on multiple occasions that “nobody has any idea” about vaccine safety profiles. Of the 378 trials in our database, the vast majority published detailed safety outcomes.

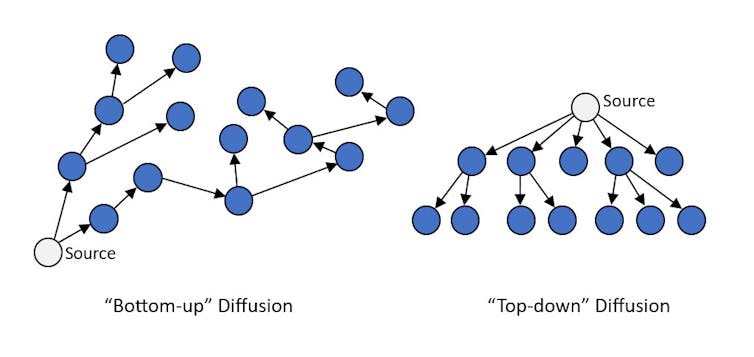

Beyond trials, the U.S. operates the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, the Vaccine Safety Datalink and the PRISM network to monitor hundreds of millions of doses for rare problems. The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System works like an open mailbox where anyone – patients, parents, clinicians – can report a post-shot problem; the Vaccine Safety Datalink analyzes anonymized electronic health records from large health care systems to spot patterns; and PRISM scans billions of insurance claims in near-real time to confirm or rule out rare safety signals.

These systems led health officials to pull the first rotavirus vaccine in 1999 after it was linked to bowel obstruction, and to restrict the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine in 2021 after rare clotting events. Few drug classes undergo such continuous surveillance and are subject to such swift corrective action when genuine risks emerge.

The conflicts of interest claim

On June 9, Kennedy took the unprecedented step of dissolving vetted members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the expert body that advises the CDC on national vaccine policy. He has claimed repeatedly that the vast majority of serving members of the committee – 97% – had extensive conflicts of interest because of their entanglements with the pharmaceutical industry. Kennedy bases that number on a 2009 federal audit of conflict-of-interest paperwork, but that report looked at 17 CDC advisory committees, not specifically this vaccine committee. And it found no pervasive wrongdoing – 97% of disclosure forms only contained routine paperwork mistakes, such as information in the wrong box or a missing initial, and not hidden financial ties.

Reuters examined data from Open Payments, a government website that discloses health care providers’ relationships with industry, for all 17 voting members of the committee who were dismissed. Six received no more than US$80 from drugmakers over seven years, and four had no payments at all.

The remaining seven members accepted between $4,000 and $55,000 over seven years, mostly for modest consulting or travel. In other words, just 41% of the committee received anything more than pocket change from drugmakers. Committee members must divest vaccine company stock and recuse themselves from votes involving conflicts.

A term without a meaning

Kennedy has warned that vaccines cause “immune deregulation,” a term that has no basis in immunology. Vaccines train the immune system, and the diseases they prevent are the real threats to immune function.

Measles can wipe immune memory, leaving children vulnerable to other infections for years. COVID-19 can trigger multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Chronic hepatitis B can cause immune-mediated organ damage. Preventing these conditions protects people from immune system damage.

Today’s vaccine panel doesn’t just prevent infections; it deters doctor visits and thereby reduces unnecessary prescriptions for “just-in-case” antibiotics. It’s one of the rare places in medicine where physicians like me now do more good with less biological burden than we did 40 years ago.

The evidence is clear and publicly available: Vaccines have dramatically reduced childhood illness, disability and death on a historic scale.

Jake Scott, Clinical Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases, Stanford University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.