Thinking builds neural networks, which is why practice improves performance.

Jennifer Robinson, Auburn University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you'd like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

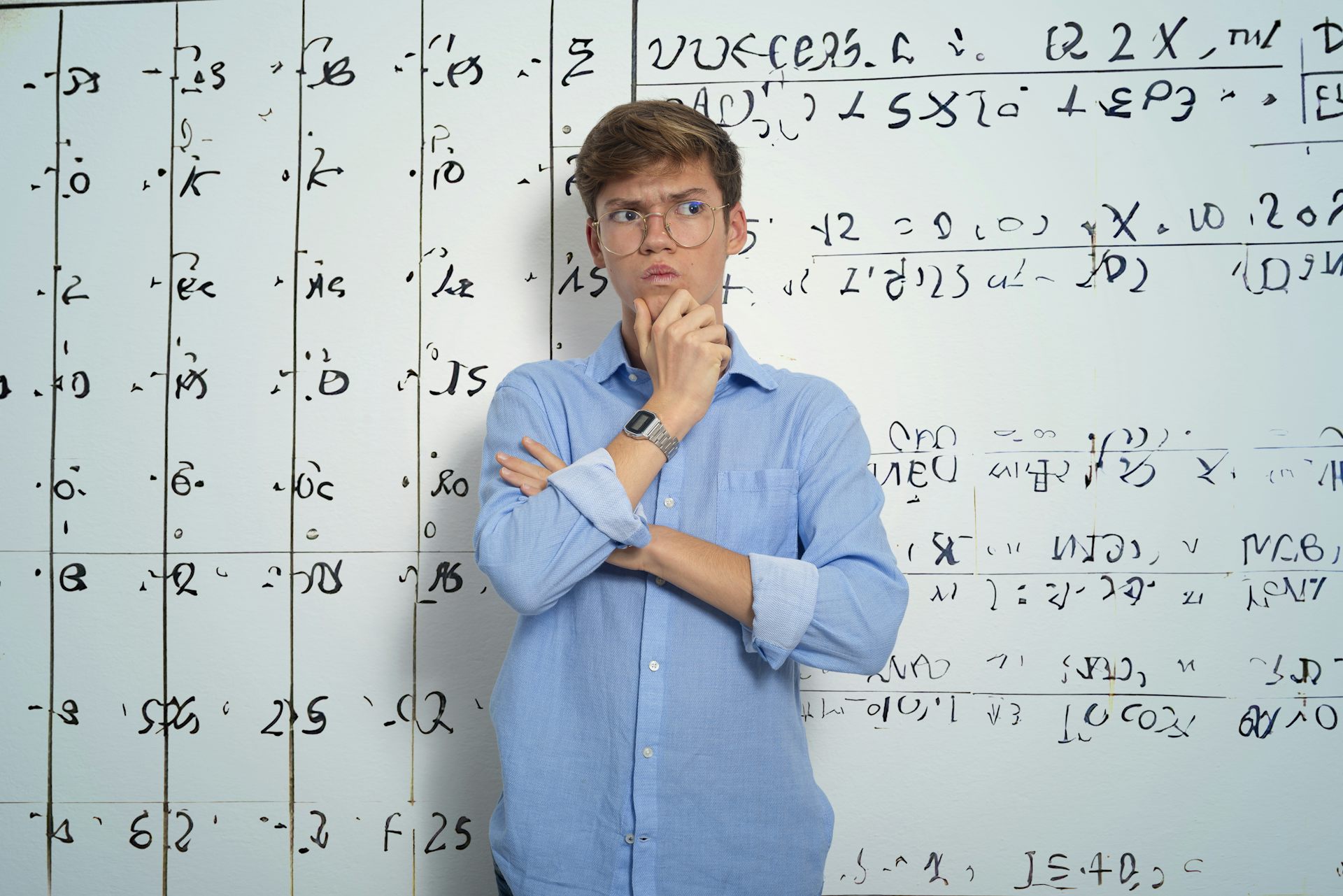

How does the brain think? – Tom, age 16, San Diego, California

Have you ever wondered how your brain creates thoughts or why something randomly popped into your head? It may seem like magic – but actually the brain is like a supercomputer inside your head that helps you think, learn and make decisions.

Imagine your brain as a busy city with lots of streets and buildings. Each part of the brain has a specific job to do, just like certain areas of a city or certain buildings serve different purposes. When you have a thought, it's like a message traveling through the city, passing from one area to another.

As a professor of psychology and neuroscience, I have studied the brain for almost 20 years. Neurologists, neuroscientists and neurosurgeons work every day to understand the brain better. And there's still a lot to learn.

Practice and repetition create skills

The neuron is a key player in the brain – these are tiny cells that send and receive signals and messages so they can communicate with each other.

Your brain has somewhere between 80 billion and 100 billion neurons. Neurons tend to group together to form neural tracts, which would be like the streets and highways in the city analogy. When you have a thought, neurons in your brain fire up and create electrical impulses. These impulses tend to travel along similar pathways and release tiny chemicals called neurotransmitters along the way.

These neurotransmitters are like the construction crew that builds the roads, making it easier for the messages to be delivered. You can imagine it as a dirt road, but as more traffic – that is, neuron signals – travel the dirt road, the road gets upgraded to a paved street. If the traffic continues, it gets upgraded to a highway.

As you learn new things and experience the world around you, these connections grow stronger. For example, when you are learning to ride a bike, you may be unsteady and find it hard to coordinate all of the different muscles along with your ability to balance. But the more you practice, the more the neurons controlling your muscles and your ability to balance fire together, which makes it much easier as you practice. Neurons are wiring together and forming neural networks.

That's why practice and repetition are important for improving your skills, whether playing the piano or learning a language. Neural networks are created and then strengthened the more times they communicate together. Scientists have a saying in this field: “Neurons that fire together wire together.” Certain thinking or behavior patterns can be chalked up to this kind of repeated synchronized activity.

Developing creativity

You are conscious of only a very small portion of the information your brain takes in. It is constantly receiving input from your senses – sights, sounds, tastes, smells and touch. When you see a cute puppy or hear your favorite song, your senses send signals to the brain, triggering a chain reaction of thoughts and emotions.

The brain also stores memories, which are like files in a computer that you can access whenever you need them. Memories help shape your thoughts and influence how you see the world.

If you remember a fun day at the beach, it might make you feel happy and relaxed. If you smell an apple pie, it may remind you of your grandma's baking. These thoughts are triggered because these pleasant associations have been formed in your brain, and through repetition, strengthened over time.

Creativity is another superpower of the brain. When you let your imagination run wild, your brain can come up with new ideas, stories and inventions. Artists, writers and scientists all use their creative brains to explore new possibilities and solve problems.

Have you ever experienced a “eureka” moment when a brilliant idea pops into your head out of nowhere? That's your brain's way of connecting the dots and coming up with a solution.

Keeping your brain healthy

Most scientists agree that sleep is really important for your brain to process information from the day and to allow it to rest and form new connections. A lot of people find that they have new ideas or thoughts after a good night's sleep. The opposite is true, too – without enough sleep, you may feel like you can't think straight.

Along with enough sleep, eat healthy foods and exercise. Just like a car needs fuel to run smoothly, your brain needs nutrients and oxygen to function at its best and to boost your thinking power.

Activities that challenge you are also great: reading, doing puzzles, playing music, making art, doing math, writing essays and book reports and journaling. Positive thinking also helps. Keep in mind that whatever you are consuming – what you're eating or what you're watching, listening to or reading – has the power to influence your brain.

Conversely, smoking cigarettes, vaping, drinking alcohol and using drugs kills brain cells. So might head injuries that can occur when playing sports such as football, soccer and bicycling – but wearing a helmet can make a big difference.

The brain is a fascinating organ that works tirelessly to create thoughts, memories and ideas. As technology continues to improve, scientists will learn more and more about how biological processes give rise to our conscious experiences. The challenges of learning about the brain are like a neuroscientific moonshot – we have a long way to go before we completely understand how it works.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you'd like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you're wondering, too. We won't be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Jennifer Robinson, Professor of Psychology, Auburn University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.