Mississippi Today

Brett Favre says the welfare agency didn’t help satisfy his volleyball pledge, but Aaron Rodgers, Jimmy Buffett and others did

Brett Favre says the welfare agency didn't help satisfy his volleyball pledge, but Aaron Rodgers, Jimmy Buffett and others did

NFL legend Brett Favre says Mississippi's welfare department didn't help satisfy his pledge to fund a new volleyball stadium at University of Southern Mississippi.

But current Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers, a charity started by Margaritaville-songwriter Jimmy Buffett, and former Gov. Phil Bryant's political action committee did.

Favre has made national news in recent years for tapping his home state's welfare agency to raise funds for the stadium, but an email Mississippi Today recently obtained shows he also raised at least $180,000 for the facility from at least four charities. These are organizations that claim to increase economic, educational or workforce opportunities for families in need.

One of the key allegations against Favre in Mississippi's welfare scandal is that he personally benefited from a scheme to divert federal funds intended to help poor Mississippians to build a volleyball stadium at his alma mater.

Mississippi Department of Human Services, which is suing Favre and dozens of others to recoup the misspent funds, draws this conclusion because, they allege, Favre personally committed funds to the project, so any welfare money used to offset that obligation was a financial benefit to Favre.

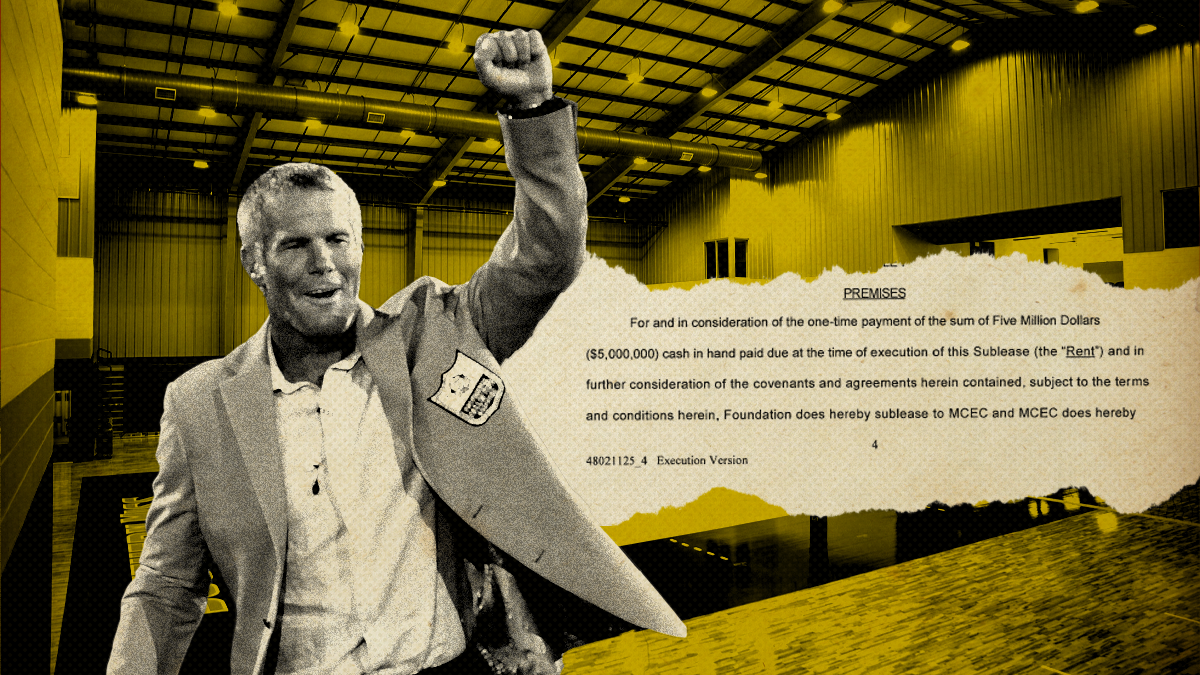

The athlete, who also directly received $1.1 million in welfare funds, did personally agree to fundraise or donate just over $1.4 million, according to a never-before-published donor agreement introduced in court this month. The document was signed by Favre, his wife, and University of Southern Mississippi Athletic Foundation President Leigh Breal.

But this guarantee came months after Mississippi Department of Human Services and one of the agency's subgrantees, nonprofit Mississippi Community Education Center, had already crafted a lease agreement allowing them to funnel $5 million in federal welfare funds to the project.

In Favre's latest reply to MDHS in early April, his attorneys accuse MDHS of using legal fallacies in its civil charges against Favre.

“MDHS's theory would effectively place no limits on UFTA (Uniform Voidable Transactions Act) liability—anyone could be sued who could in any way be deemed to have reaped some undefined benefit from a transfer,” Favre's latest motion reads. “That of course is not the law in Mississippi or anywhere else.”

Since Mississippi Today first uncovered in February of 2020 that officials used welfare money to build the volleyball stadium, the entities involved have not made public a full accounting of who paid for the roughly $8 million facility, which would show who contributed to the project following Favre's commitment so he didn't personally have to.

An email recently obtained by Mississippi Today reveals publicly for the first time that, at least by the time initial arrests were made, the following individuals had made contributions towards Favre's pledge:

- American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation Inc. (6/22/18): $100,000

- Imagine Mississippi Political Action Committee (6/4/18): $2,500

- Anonymous Donor (7/30/18): $150,000

- SFC Charitable Foundation (7/10/18): $33,378

- Brett Favre (8/16/18): $50,000

- Steel Dynamics Foundation (7/9/19): $25,000

- Aaron Rodgers (10/10/19): $10,000

- Howard Deneroff (1/7/20): $500

- Jimmy A. Payne Foundation (1/13/20): $22,000

- Matt Helms (1/24/20): $360,000

Favre attached this email to his most recent court filing, but redacted the donors' names. Mississippi Today retrieved an unredacted copy, which University of Southern Mississippi should have produced to the news organization in response to a public records request last year, but did not.

The list does not implicate Rodgers, Buffett, or any other private donor in the welfare scheme. But the email serves as a key piece of evidence in Favre's defense.

The gifts cited total just over $650,000. Documents reflecting the total amount Favre personally contributed towards the project have not been made public, but his lawyer Eric Herschmann told conservative sports podcaster Jason Whitlock in a February interview that Favre donated over a million dollars of his own money to the facility. Also, The Athletic first reported that from 2018 to 2020, the same years Favre had an obligation to fund the volleyball construction, his charity Favre 4 Hope donated nearly $133,000 to USM Athletic Foundation.

In addition to the $5 million in welfare funds that went towards the facility, Nancy New, founder of the nonprofit in charge of spending welfare funds, alleged that former Gov. Bryant directed her to make $1.1 million in payments to Favre to help Favre raise funds for the stadium — an allegation Bryant has denied to the press.

But a spokesperson for the athlete recently confirmed that Favre did not use that money on the facility.

“Brett fulfilled his only obligation to USM. No funds he received from MCEC went towards the wellness center. Brett both solicited donations and often asked individuals or groups to send money to USM instead of paying him for services he provided,” a spokesperson for Favre said in a statement last week.

While a complete and reliable breakdown of the funds used to construct the facility has not been made public, outside counsel for the athletic foundation recently confirmed in an email requested by Favre's wife Deanna Favre that the Favres “satisfied the obligations of their Donor Agreement by raising or paying the Foundation in excess of the pledged amount of at least $1,406,747.55 for the Volleyball Wellness Center.”

“This includes cash donations given directly by Brett and Deanna Favre and other amounts contributed at the request of Brett and Deanna Favre,” Ridgeland-based attorney Scott Jones wrote in the Mar. 23, 2023 email to Favre's attorneys.

University of Southern Mississippi has refused to answer several questions from Mississippi Today about the volleyball project, citing litigation.

Favre began fundraising for the new volleyball stadium at USM, where his daughter played the sport, in 2017 – no one argues that. What's in dispute, and belabored in lengthy court motions back and forth, is whether Favre promised to come up with the funding for construction at the outset of the project.

Favre argues in his motion to dismiss the civil suit against him that the $5 million paid in 2017 couldn't have satisfied his $1.4 million guarantee in 2018 since the payment came before the pledge. MDHS alleges that Favre made a “handshake deal” near the inception in 2017, which is the only reason the university proceeded with the project, meaning he was on the hook for the funding the entire time.

By mid-2017, Favre had supposedly contributed $150,000 towards the volleyball project, according to an April 2017 email from Morrison to then-USM Athletic Director Jon Gilbert. After struggling to secure many more big donors, Gilbert involved nonprofit founder Nancy New, who had already entered at least one lease agreement with USM for the purpose of using grant money to make building renovations on campus – a purchase that has yet to be scrutinized.

“Brett and Deanna have agreed to help with fundraising for the facility,” Gilbert wrote in a July 16, 2017, email to New. “We currently have $1.2 million in hand from a variety of people that have committed to the project … I will find out what Brett's schedule is Tuesday and coordinate a time he can stop by that works for everyone.”

In the days and weeks following, Favre and New discussed by text the challenges in using federal grant funds for the volleyball stadium, since federal law prohibits spending of these dollars on brick-and-mortar construction projects. Favre suggested the nonprofit hire and pay him for marketing services – which are allowed under the federal rules – and that way he could pass the money to the athletic foundation.

“Will the public perception be that I became a spokesperson for various state funded shelters,schools,homes etc….. And was compensated with state money? Or can we keep this confidential,” Favre texted New in a never-before-published text first introduced into court last month.

New responded that only she, her son Zach New and former Mississippi Department of Human Services director John Davis would have information about the payment – a product of the secrecy shrouding the welfare program.

“So if we keep confidential where money came from as well as amount I think this is gonna work,” Favre wrote.

The nonprofit eventually made two $2.5 million payments through a lease agreement with USM Athletic Foundation in November and December of 2017. For this, Zach New pleaded guilty to state charges of defrauding the government. To make the lease appear legit, the nonprofit said it would occupy classrooms inside the stadium, where it would conduct programming for underprivileged people. Later that December, the nonprofit also made the first $500,000 payment directly to Favre under an agreement that he would cut a radio ad for their anti-poverty program.

In the following months, Favre learned that the construction bids had come in much higher than expected, and that USM Athletic Foundation wouldn't be able to begin building the facility until they could guarantee more funding was coming.

In April of 2018, an email stated that Favre's original gift of $500,000 towards the volleyball stadium would be reduced to $250,000 after he instructed the university to transfer half to the construction of a beach volleyball arena. (His daughter had moved from the indoor team to the beach team).

In order for work to begin, Favre signed the $1.4 million donor agreement, ensuring that he'd raise or cover the rest of the cost, on May 2, 2018.

About a week later on May 10, New texted Favre, “I am making some progress on our money needs. What amount out of the whole loan that you signed would be most helpful right now? John and I may have a plan!!”

This text appears to show that Favre and New had planned for the nonprofit to contribute towards his guarantee.

On May 17, New texted Favre, “Good news. I have a little money for the ‘project' – $500,000! Do you want me to send to the Athletic Dept. Or to your foundation.”

New sent the payment in the following weeks to Favre's for-profit company Favre Enterprises, Inc., according to the State Auditor's Office.

The text suggests that they both understood the payment to Favre – paid under what was essentially a sponsorship agreement – was ultimately for the purpose of supporting construction at USM.

“While $1,100,000 was paid based on a contract for public appearances, and Favre did record a radio advertisement, the payment was intended, as requested by Bryant, to help Favre raise funds for construction of the Volleyball Facility,” reads New's October filing in the civil case.

Through his counsel, Bryant has denied the allegation to Mississippi Today. At the point this payment was made, Favre had not yet cut the radio ad.

“Favre knew that this was a sham designed to allow MDHS to cover Favre's commitment to fund construction of the volleyball facility,” MDHS alleges in its amended complaint.

Despite their plans, Favre didn't use the money for the alleged purpose he received it, according to his spokesperson's statement.

Also in June of 2018, Favre secured donations for the facility from American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation Inc. and Bryant's PAC Imagine Mississippi Political Action Committee.

Bryant was still governor when Imagine Mississippi PAC donated $2,500 to the volleyball project in June of 2018. Bryant started the PAC by closing his campaign-finance account and transferring the bulk of the $1.05 million he had left over to the new organization in 2017 shortly after winning his second term. The PAC's stated goal is to support conservative candidates and officials. It spent about $220,000 in 2017, $216,000 in 2018, $307,000 in 2019 and $23,000 in 2020. It did not file an annual report for 2021 or 2022 or a notice of termination, according to what is available on the Secretary of State's Office website.

American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation Inc., which donated $100,000 towards the volleyball stadium, is a nonprofit focused on supporting programs in academic achievement, healthy youth development, economic opportunity, such as job training, and community resilience, including food, housing and daycare.

A spokesperson for the foundation told Mississippi Today that Favre played in its golf tournament for several years, drawing large crowds and helping fundraising efforts for its nonprofit partners. “For his participation, we made charitable contributions to a few select organizations of his choice, including the University of Southern Mississippi. Supporting colleges and universities, including programming that impacts students, aligns to the mission of the American Family Insurance Dreams Foundation.”

The spokesperson did not respond to follow up questions about what programming the foundation thought its gift was supporting.

In July of 2018, Singing For Change Charitable Foundation — a charity founded by Pascagoula-native and USM alum Jimmy Buffett with the slogan, “Turning good vibes into good deeds” — gave $33,378 for the facility. Its website says it gives grants to small, grassroots nonprofits across the country that help people “get back on their feet, back into homes, back to work, find meaningful jobs, become better educated, and thrive according to their definition.” One dollar for every concert ticket Buffett sells on tour goes towards his foundation.

“Our contribution on behalf of student wellness at USM was made in good faith to the University's foundation,” a spokesperson for SFC Charitable Foundation said in a statement to Mississippi Today. “… When any nonprofit goes astray and mismanages funds, it's a sad day for those of us in the sector but especially distressing and financially stressful for local organizations handling the fallout. As Jimmy's tour resumes this spring, we will to continue to support people living on the margins across the U.S.”

An anonymous donor also contributed $150,000 towards the volleyball stadium that month, according to the Morrison email, and Favre himself donated $50,000 the next month.

Despite personally receiving $1.1 million from the nonprofit, Favre continued in the following months and years to lobby welfare officials, other government officials and current Gov. Tate Reeves in an attempt to secure more public funds to satisfy his obligation.

But this never happened: “Zero public funds went towards satisfying this voluntary pledge,” the spokesperson for Favre confirmed for the first time to Mississippi Today recently.

It's unclear how Favre may have used the $1.1 million he received from MCEC, which he has since repaid to the state. When he spoke to his associates about his debt in the project, the number varied from $1.1 million or $1.2 million in March of 2019 to $1.8 million in September of 2019.

By July of 2019, Davis had been ousted for suspected fraud and Favre was becoming worried.

“Nancy has been awesome to me and has paid 4.5 million for a 7 million dollar facility. And she said it was all gonna be taken care of until this morning,” Favre wrote to his business associate, Jake Vanlandingham, founder of a pharmaceutical startup company called Prevacus, on July 16, 2019. This text was first published by Mississippi Today in its investigative series “The Backchannel.”

(MDHS also alleges that Favre participated in the funneling of $1.7 million in welfare money to Prevacus, to which New has pleaded guilty criminally, and that Favre is liable. In response, Favre's attorneys argue, “All Favre is alleged to have done with respect to Prevacus is to have introduced VanLandingham to New … This is insufficient to state a claim that Favre agreed to join a conspiracy … if this conduct was sufficient to join a conspiracy, then MDHS could also add as co-conspirators Southern Miss Athletic Director Jon Gilbert for his role in introducing New to Favre and attending the meeting.”)

“Suddenly she said I don't think I can do anymore,” Favre wrote to Vanlandingham, referring to New, according to “The Backchannel” texts. “So now I am looking at a big pay out.”

The same month, Steel Dynamics Foundation donated $25,000 towards Favre's volleyball pledge. Steel Dynamics Foundation is the foundation associated with Steel Dynamics Inc., a Fort Wayne, Indiana-based company that has manufacturing sites in Mississippi and recently received $247 million in tax incentives from the state. The foundation's website says its goal is to improve the quality of life and local economies in the communities where its employees work.

By September of 2019, Favre's debt had apparently grown. “I have more shit going on not to mention a very likely 1.8 million note coming due that I thought was covered,” Favre texted Vanlandingham.

That month, Favre secured a meeting with Bryant and the new welfare director, Christopher Freeze, who replaced Davis. They discussed pushing additional grant funds to the volleyball project. After the meeting, Bryant encouraged Favre by text that “We are going to get there. … But we have to follow the law.”

Freeze told Mississippi Today he rejected the proposal and there's been no evidence that any additional welfare money went to the project after this point.

The next month, Aaron Rodgers – the quarterback who replaced Favre at the Green Bay Packers, prompting a memorable feud in sports pop culture history – donated $10,000 to the facility, according to the Morrison email. Favre had also talked to Vanlandingham in 2019 about asking for Rodgers' support with the pharmaceutical venture. Rodgers' agent did not return emails or a call from Mississippi Today.

By early 2020, Favre was desperately trying to come up with the rest of the funding. According to the Morrison email, he then secured $500 from Howard Deneroff, executive producer of Westwood One Sports, an NFL broadcaster. Favre had asked Deneroff to donate in exchange for a sit-down interview on the network. Favre also collected $22,000 from the Jimmy A. Payne Foundation, the foundation of a USM alum and businessman, and $350,000 from Matt Helms, owner of a sports memorabilia store in south Mississippi.

But it wasn't enough. Favre even attempted to involve the Mississippi Community College Board, incoming Gov. Tate Reeves and the Legislature.

Bryant texted then-USM President Rodney Bennett about Favre's insistence.

“The bottom line is he personally guaranteed the project, and on his word and handshake we proceeded,” Bennett texted Bryant on Jan. 27, 2020, shortly after the outgoing governor left office. “It's time for him to pay up – it really is just that simple.”

MDHS uses this text to substantiate its allegation that Favre committed the funds before the welfare payment, since the athletic foundation proceeded with the project by hiring architects to start drafting renderings of the building in July of 2017.

All of this together, MDHS alleges, “support the reasonable inference that Favre personally committed to guarantee the volleyball facility's construction at the outset of the project.”

Favre's attorneys push back: “MDHS takes this text message completely out of context—it clearly related to efforts by Favre to raise funds to meet his 2018 written commitment,” Favre's recent reply states. “MDHS takes a giant and unsupported leap of faith in claiming that the text message related to some different, earlier commitment.”

On the day of the initial arrests in February of 2020, Morrison, the associate athletic director, sent Favre the email describing “the following gifts that have been applied towards your commitment to the Volleyball Facility.”

Asked about the timing of the email, the Favre spokesperson said, “it is purely coincidental.”

The indictment, which was made public that day, had named Prevacus and its affiliate PreSolMD, alleging that the News had embezzled welfare funds from their nonprofit to invest in the companies.

About a week later, Vanlandingham texted Favre, saying he wasn't sure if one of their potential investors was going to follow through with his contribution “given this MS embezzlement shit.”

Vanlandingham asked the athlete to make another $50,000 donation so PreSolMD could begin developing what it called a “pregame cream” that it promised could prevent concussions.

“…I would but up to my eyeballs in vball debt,” Favre responded.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

PSC axes solar programs in light of EPA funds, advocates file lawsuit

Advocates from some of the state's conservation groups — such as Audubon Delta, Mississippi Sierra Club and Steps Coalition — spoke out Wednesday against a recent decision by the Mississippi Public Service Commission to suspend several solar programs, including “Solar for Schools,” less than two years after the previous commission put them in place.

“This is particularly disappointing because the need for these incentives in the state of Mississippi is significant,” said Jonathan Green, executive director of Steps Coalition. “Energy costs in the South, and in particular the region known as the Black Belt, are higher than those in other parts of the country for a number of reasons. These regions tend to have older energy generation infrastructure, and housing that has not been weatherproofed to modern standards. For many low- to moderate-income residents in the state of Mississippi, energy burden and energy insecurity represent real daily economic challenges.”

The PSC voted 2-1 at its April docket meeting to do away with the programs, reasoning in part that new funds through the Inflation Reduction Act would be available to the state. About 10 days later, the Environmental Protection Agency awarded $62 million to the state, through the Hope Enterprise Corporation, to help low-income Mississippians afford adding solar power to their homes. The funds are part of the Biden Administration's Solar for All program, one of the several recent federal initiatives aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The PSC decision ended three programs the previous commission put in place to encourage wider adoption of solar power through the two power companies it regulates, Entergy Mississippi and Mississippi Power: “Solar for Schools,” which allowed school districts to essentially build solar panels for free in exchange for tax credits, as well as incentives for low-income customers and battery storage.

Last Friday, the Sierra Club filed lawsuits in chancery courts in Hinds and Harrison counties against the commission, arguing the PSC broke state law by not providing sufficient reasoning or public notice before making the changes. Advocates also argued that new funding going to Hope Enterprise won't go as far without the PSC's low-income incentives.

The programs were part of a 2022 addition to the state's net metering rule, a system that allows homeowners to generate their own solar power and earn credits for excess energy on their electric bills. Mississippi's version is less beneficial to participants than net metering in most states, though, because it doesn't reimburse users at the full retail cost. Mississippi's net metering program itself is still in tact.

Northern District Commissioner Chris Brown said that, while he supported efforts to expand solar power, he didn't think programs that offer incentives from energy companies were fair to other ratepayers.

“It's the subsidy that we take issue with,” Brown said at the meeting. “It's not the solar, it's not the helping the schools. We just don't think it's good policy to spread that to the rest of the ratepayers.”

Brown and Southern District Commissioner Wayne Carr voted to end the programs, while Central District Commissioner De'Keither Stamps voted against the motion. All three are in their first terms on the PSC. Brown's position is in line with what the power companies as well as Gov. Tate Reeves have argued, which is that programs like net metering forces non-participants to subsidize those who participate.

Robert Wiygul, an attorney for the Mississippi Sierra Club, countered that argument during Wednesday's press conference, saying that net metering actually helps non-participants by adding more power to the grid and reducing the strain on the power companies' other infrastructure. Moreover, he said, the PSC hasn't offered actual numbers showing that non-participants are subsidizing the program.

“Look, if the commission wants to talk about that, we are ready to talk about it,” Wiygul said. “But what we got here is a situation where these two commissioners just decided they were going to do this. We don't even know what that claim is really based on because it hasn't been through the public notice and hasn't been through the public comment process.”

While no schools had officially enrolled in “Solar for Schools,” which went into effect in January of last year, Stamps told Mississippi Today that there were places in his district getting ready to participate in the very programs the PSC voted to suspend.

“My issue was we should have talked to the entities that were going through the process to (understand what they were doing) to participate in the programs before you eliminate the programs,” he said.

Several school districts in the state are already using solar panels thanks to funding from a past settlement with Mississippi Power. Officials there told Mississippi Today that the extra power generated from the panels has freed up spending for other educational needs. During the public comment period for the 2022 net metering update, about a dozen school district superintendents from around the state wrote in to support the initiative. Ninety-five school districts in the state would have been eligible for the program because they receive power from Entergy Mississippi or Mississippi Power.

Former commissioner Brent Bailey, who lost a close reelection bid in November to Stamps, was an advocate for the schools program that the PSC created while he was there. At the April docket meeting, he pleaded with the new commission to reconsider, arguing that the new federal funding won't have the same impact without those programs.

“My ask is to at least give this program a chance, see where it goes, and hear from stakeholders that have participated,” Bailey said. The solar programs, he added, weren't just about expanding renewable energy, but taking advantage of a growing economy around solar power as well: “We can just stand by and watch it go by, or we can participate in this and bring economic development to the state.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: In or out (of the NCAA Tournament)?

College baseball's regular season is in its last week, which means baseball bracketology is a popular activity. State needs to finish strong to become a Regional host. Southern Miss probably has already punched its ticket as a 2- or 3-seed. Ole Miss, playing its best baseball presently, needs victories, period. Meanwhile, the State High School softball tournament is this week in Hattiesburg, and the state baseball tournament comes to Trustmark Park in Pearl next week.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=358148

Mississippi Today

Reeves again blocks funds for LeFleur’s Bluff project in Jackson

For the third consecutive year legislative efforts to direct state money to renovate LeFleur's Bluff in Jackson have been stymied, thanks in large part to Gov. Tate Reeves.

Earlier this week, the Republican governor vetoed a portion of a bill that directed $14 million to the office of Secretary of State Michael Watson for work on developing and improving a nature trail connecting parks and museums and making other tourism-related improvements in the LeFleur's Bluff area.

It is not clear whether the Legislature could take up the veto during the 2025 session, which begins in January, though, that's not likely. The Legislature had the option to return to Jackson Tuesday to take up any veto, but chose not to do so.

Of the project, Watson said, “Our office was approached late in the session about helping with a project to revitalize LeFleur's Bluff. As Mississippi's state land commissioner, I was more than happy to help lead this effort not just because it's a natural fit for our office, but also because I believe Mississippi needs a thriving capital city to retain our best and brightest. Investing state funds in state property on a project to enhance the quality of life in Jackson makes good sense.

“Unfortunately, some only support it when it equates to campaign contributions. Sadly, through the line-item veto of the appropriation, Mississippians will once again wait another year for the opportunity to benefit from state investments for the greater public good.”

Various groups, such as representatives of the Mississippi Children's Museum and many other community leaders have been working on the project for years. The area already is the home of the Children's Museum, Museum of Natural History, Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum and a state park.

The issues with LeFleur's Bluff first arose in 2022 when Reeves vetoed a $14 million appropriation that in part was designed to redesign and create a new golf course in the area. Previously, there had been a nine-hole, state-owned golf course operated by the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks at LeFleur's Bluff State Park.

In 2022, the LeFleur's Bluff project was one of literally hundreds of projects funded by the Legislature – many of which was tourism projects like LeFleur's Bluff. The governor only vetoed a handful of those projects.

When issuing the LeFleur's Bluff veto, Reeves said the state should not be involved in funding golf courses.

Then last year $13 million was directed to the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks to spend on the LeFleur's Bluff project. But legislative leaders said state money would not go toward a golf course.

Lawmakers opted to transfer the project to the Secretary of State's office late in the 2024 session, apparently in part because they felt the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks had not made enough of an effort to begin the project.

Lynn Posey, executive director of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks, said that before moving forward with the project, “We felt like we needed to do engineering work and see what the situation was. We never got a chance to move forward” because the Legislature redirected the money.

Posey said an engineer's report was needed because “it is a unique piece of land.” He said much of the land is prone to flooding.

He said before that work could begin the Legislature switched the authority to the Secretary of State's office. Posey was appointed to his current position by Reeves, whose office had no comment on the veto.

Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann said after the governor's veto, “Projects like the LeFleur's Bluff development are critical to the Capital City, the wider metropolitan area, and our state. Public parks add to the quality of life for our citizens. I am hopeful the individuals involved in this project, including those at the Mississippi Children's Museum, will continue their work to improve this state asset.”

While the Constitution instructs the governor to provide to the Legislature a reason for any veto, Reeves did not do so this year when vetoing the money going to the Secretary of State's office.

On Monday, the governor also vetoed a portion of another bill dealing with appropriations for specific projects. But in this case, the veto was more of a technicality. The bill was making corrections to language passed in previous sessions. In that language were five projects the governor vetoed in 2022.

The language, as it was written, would not have revived those previously vetoed projects, the governor said. But Reeves said he vetoed the five projects out of caution. He did the same in 2023 when those five projects, which included money appropriated in 2022 for the Russell C. Davis Planetarium in Jackson, were carried forward in a bill also making corrections to previously passed legislation.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

-

SuperTalk FM3 days ago

Martin Lawrence making 3 stops in Mississippi on comedy tour

-

Our Mississippi Home2 days ago

Beat the Heat with Mississippi’s Best Waterparks

-

Mississippi News6 days ago

Man arrested for allegedly breaking into home, robbing owner

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Lawmakers may have to return to Capitol May 14 to override Gov. Tate Reeves’ potential vetoes

-

SuperTalk FM6 days ago

Couple arrested after husband received unemployment benefits while in prison

-

Mississippi News Video5 days ago

Local dentists offer free dental care in Amory

-

Our Mississippi Home3 days ago

Charlie’s U-Pik: Opening Soon for the Summer Season

-

Mississippi News5 days ago

Bond set for West Point couple accused of killing their child

![HIGH SCHOOL SOFTBALL: Vancleave @ East Central (5/9/2024) [5A Playoffs, South State]](https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/1715460379_maxresdefault-80x80.jpg)