Mississippi Today

On this day in 1901

Aug. 4, 1901

Louis Armstrong, trumpeter known around the globe as “Satchmo,” was born in an impoverished area of New Orleans known as “the Battlefield.”

“As a boy, he released his energy in a variety of ways — not always socially acceptable,” singer Mahalia Jackson wrote. “One of Louis' last transgressions as a youth, at the age of 12, was to fire a gun into the air during a New Year' Eve celebration. He was arrested and sent to reform school.”

The two-year stay had an unexpected effect on the lad — he learned to play the cornet. After his release, he gravitated to where he could listen to music, surviving by selling newspapers and whatever work he could find. He eventually befriended one of the great band leaders of the day, Joe “King” Oliver, who gave him his first cornet.

Armstrong's inventive playing and gravelly voice reached far beyond jazz, prompting singer Bing Crosby to declare, “He is the beginning and end of music in America.”

He broke down barriers, becoming the first Black American to host a nationally broadcast radio show and made countless appearances on radio, television and film. Often silent on politics, Armstrong made his own stand for civil rights in 1957 when he balked at participating in a U.S. government-sponsored tour of the Soviet Union after nine Black students were blocked from entering a Little Rock school. Complaining about President Eisenhower's handling of the problem and the way “they are treating my people in the South,” he turned down the government's request. “It's getting almost so bad a colored man hasn't got any country.”

In response to his comments, the FBI opened an investigation of him. He performed to the end, dying in 1971, a month before he would have celebrated his 70th birthday.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Crime, potholes, homelessness: Jackson turns to data for answers

Jackson is laying the groundwork to use data across city departments and use it to address, initially, youth crime, homelessness and infrastructure needs.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba is a member of the Bloomberg Philanthropies City Data Alliance, which trains mayors to understand data and use it to make decisions that can improve city services.

“If we don't have proper data about where we stand, we can't set sufficient goals of where we want to go in the future,” Lumumba said, adding that data also allows goals to be measured and followed.

Twenty mayors from North and South America are part of the cohort, which met last spring. The mayor said the program is an opportunity to learn from other city leaders and see what Jackson is doing well. As part of a network of mayors, he can reach out to them even after the program is over.

James Anderson, head of government innovation programs for Bloomberg Philanthropies, said the mayor joined the program last year with an ambitious application that articulated a vision of changing a work culture that did not use data before.

The use of data, including in city settings, has been a trend for the past decade, but the Bloomberg program is looking for mayors who want to take greater steps, Anderson said.

For example, Jackson is now one of the few cities across America with a formal citywide data strategy, he said.

“This alliance was the next step to help the most ambitious cities make ambitious gains,” Anderson said.

Lumumba hopes using data can help the city be more proactive in its decision making and dealing with crises. As part of the citywide strategy, departments are also getting help with accessing data, understanding it and using it more in their daily work.

One of his goals is to use data to reduce youth violence by addressing root causes of violence.

Data has helped the city see that the sharpest increase in violence has been youth, and that has led to focused efforts for that population, such as work through the Office of Violence Prevention & Trauma Recovery and a youth curfew approved at the beginning of the year.

One challenge of a youth curfew is finding a place to house those who violate it, Lumumba said. There is a county facility, the Henley-Young Juvenile Justice Center, but it holds those charged with misdemeanors or felonies, including those who face adult criminal charges.

A way to provide space for youth to go and to give them access to programs is through curfew centers, which Lumumba said are in the works. In a March episode of a city talk show, he said there are plans to partner with a local church to open a curfew center.

Lumumba envisions the center as a place staffed with social workers and professionals to provide young people with extra curricular activities and teach them conflict resolution skills.

Through the program, another of the mayor's goals is to use data to get Jackson to “functional zero” homelessness, which is the point where the same number of people entering homelessness exit homelessness in the same month.

Although Lumumba said there are regional challenges to addressing the issue, recent counts show that 67 of the 93 people experiencing homelessness in central Mississippi were in the metro Jackson area.

Nearly 1,000 people experienced homelessness in Mississippi in 2023, according to the Annual Homelessness Assessment Report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The common way to get these numbers are through “point-in-time” counts, which are completed annually by continuum-of-care service providers across the country in one day and gives an estimate of sheltered and unsheltered populations.

Lumumba said he would like data collected in Jackson to go further because the current point-in-time counts are insufficient to understand what circumstances people are facing. Better data can help determine who needs housing and maybe, additionally, services for mental health or substance addiction, he said.

Lumumba's last data-related priority is about infrastructure needs and assessing the condition of roads and systems.

He said a need is clear if residents report a road needing to be paved or a burst pipe. But beyond that, he said there is more work to be done, such as how paving projects relate to each other and how to create more mobility within the city.

A program like the City Data Alliance can help cities make policy decisions, streamline services and look forward, said Dallas Breen, the executive director of the John C. Stennis Institute of Government and Community Development at Mississippi State University, which provides research, training and services to municipalities, counties and government agencies.

Like Jackson is doing, Breen said it is helpful to work with a data scientist who can help city leaders and staff and understand the data they are looking at and how to collect it.

“The more data you have, the more informed your decisions will be,” Breen said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1963

MAY 28, 1963

The nation's most violent reaction to a sit-in protest took place when a mob attacked Black and white activists at a Woolworth's lunch counter in Jackson, Mississippi.

One of them, Tougaloo College professor John Salter, said, “I was attacked with fists, brass knuckles and the broken portions of glass sugar containers, and was burned with cigarettes. I'm covered with blood, and we were all covered by salt, sugar, mustard, and various other things.”

Salter and fellow protesters Joan Trumpaeur and Anne Moody, who were both Tougaloo students, can be seen in the famous picture of the event. The protest came eight days after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that state enforcement of restaurant segregation is a violation of the 14th Amendment.

M.J. O'Brien's book, “We Shall Not Be Moved: The Jackson Woolworth's Sit-In and the Movement It Inspired”, describes that event.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

This DeSoto Co. hospital transfers some patients to jail to await mental health treatment

This article was produced for ProPublica's Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today and co-published with the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, the Sun Herald and MLK50. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

When Sandy Jones' 26-year-old daughter started writing on the walls of her home in Hernando, Mississippi, last year and talking angrily to the television, Sandy said, she knew two things: Her daughter Sydney needed help, and Sandy didn't want her to be held in jail again to get it.

A year and a half earlier, during Sydney Jones' first psychotic episode, her mother filed paperwork to have her involuntarily committed, a legal process in which a judge can order someone to receive mental health treatment. After DeSoto County sheriff's deputies showed up at Sydney's home and explained that they were detaining her for a mental evaluation, Sydney panicked and ran inside. Following a struggle, deputies cuffed and shackled her and drove her to the county jail, where people going through the commitment process are usually held as they await mental health treatment elsewhere.

Over nine days in jail, Sydney Jones said, she believed her tattoos were portals for spiritual forces and felt like she had been abandoned by her family. In an interview, she said that the experience was so traumatic that she became anxious when she drove, afraid she could be arrested at any moment.

The second time Sydney Jones experienced delusions, in 2023, a family member contacted the local community mental health center for help. Police officers with mental health training came and called an ambulance to take Jones to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, part of a large, religiously affiliated nonprofit hospital system. But because the hospital doesn't have a psychiatric unit, after a few days it sent her to the jail to wait for eventual treatment in a publicly funded facility. Like the first time, she hadn't been charged with a crime.

Roughly 200 people in DeSoto County were jailed annually during the civil commitment process, most without criminal charges, between 2021 and 2023. About a fifth of them were picked up at local hospitals, according to an estimate based on a review of Sheriff's Department records by Mississippi Today and ProPublica. The overwhelming majority of those patients, according to our analysis, were at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, the largest in this prosperous, suburban county near Memphis.

“That would just be unthinkable here,” said Dr. Grayson Norquist, the chief of psychiatry at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, a professor at Emory University and the former chair of psychiatry at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi.

Norquist was one of 17 physicians specializing in emergency medicine or psychiatry, including leaders in their fields, who said they had never heard of a hospital sending patients to jail solely to wait for mental health treatment. Several said it violates doctors' Hippocratic oath: to do no harm.

The practice appears to be unusual even in Mississippi, where lawmakers recently acted to limit when people can be jailed as they go through the civil commitment process. Sheriff's departments in about a third of the state's counties, including those that appear to jail such people most frequently, responded to questions from Mississippi Today and ProPublica about how they handle involuntary commitment. They said they seldom, if ever, take people who need mental health treatment from a hospital to jail. At most, said sheriffs in a few rural counties, they do it once or twice a month.

But in DeSoto County, hospital patients were jailed about 50 times a year from 2021 to 2023, according to the news outlets' estimate, which was based on a review of Sheriff's Department dispatch logs, incident reports and jail dockets.

At least two people have died soon after being taken from Baptist-DeSoto to a county jail during the commitment process, according to documents submitted for lawsuits filed over their deaths. One person died by suicide hours after arriving at the DeSoto County jail in 2021; the other died of multisystem organ failure after being jailed for three days in neighboring Marshall County in 2011. James Franks, an attorney who handles commitments for DeSoto County, said officials had no reason to believe that the woman who killed herself was suicidal. DeSoto County made a similar argument in a court filing in an ongoing lawsuit over that death, which didn't name the hospital as a defendant. In lawsuits over the other death, a judge dismissed Marshall County and the sheriff as defendants, and a jury found that Baptist-DeSoto wasn't liable.

Baptist-DeSoto officials said the hospital hands some patients over to deputies to take them to jail because those patients need dedicated treatment that the hospital can't provide and nearby inpatient facilities are full. Most people who need inpatient treatment agree to be transferred to a behavioral health facility, according to Kim Alexander, director of public relations for Baptist Memorial Health Care Corp. But in a relatively small number of cases, she wrote in an email, patients are deemed dangerous to themselves or others and don't agree to treatment, so they need to be committed. When that happens, she said, it's the county's responsibility to decide where to house them.

“We discharge mental health patients with the hope they will be transferred to a mental health facility that can provide the specialized care they need,” Alexander wrote in a statement. Jailing people who need mental health care is “not the ideal option,” she wrote. “Our hearts go out to anyone who cannot access the mental health care they need because behavioral health services are not available in the area.”

But doctors elsewhere said even if psychiatric facilities are full, Baptist-DeSoto doesn't have to send patients to jail. They said the hospital could do what hospitals elsewhere in the country do: keep patients until a treatment bed is available.

“This is a principle of emergency medicine: You care for all people, under all circumstances, at any time,” said Dr. Lewis Goldfrank, who spent 50 years working in emergency medicine, including at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. Sending patients to jail because of their illness, he said, “is just unethical and irresponsible.”

Sandy Jones said she was in disbelief when it happened to her daughter. If Sydney has another psychotic episode, Sandy Jones said she won't try to get help in DeSoto County. “I will tie her up until it's over.”

Headed to Jail in a Hospital Gown and Handcuffs

Baptist, the largest and oldest hospital in DeSoto County, sits right off the interstate amid big-box stores and chain hotels in Southaven, Mississippi. It's the first place many residents think of when they need medical help. Since 2017, it has served as the drop-off point for the county's crisis intervention team, which was established to give law enforcement a way to help people with mental illness without bringing them to jail.

But when people show up in the emergency department needing inpatient psychiatric treatment, they don't get it at Baptist-DeSoto. Instead, a crisis coordinator sets about finding some other place for them. If patients agree to treatment, they may be able to go to a publicly funded crisis unit, the closest of which is 50 miles away, or to a private psychiatric hospital. If they don't, the crisis coordinator pursues commitment, which means turning patients over to the Sheriff's Department. And because the Sheriff's Department usually won't transport patients over a long distance multiple times for a court hearing and eventual treatment, those patients usually go to jail.

That was the case with Sydney Jones. After she arrived at the hospital in April 2023, a psychiatrist contracted by the hospital evaluated her and concluded that she needed inpatient treatment. Jones was prescribed antipsychotic medication, admitted to the hospital, placed in her own room and monitored by a security guard.

Meanwhile, a staffer for Region IV, the local nonprofit community mental health center that works with Baptist-DeSoto to place patients who need treatment, was trying to find someplace for Jones other than the hospital. Catherine Davis, the crisis coordinator, concluded that Jones would need to be committed.

The next day, Davis contacted Jones' cousin, who had tried to get Jones help, and asked the cousin to initiate commitment proceedings. (Region IV's contract with Baptist-DeSoto requires it to try to get a patient's family member or friend to file commitment paperwork before doing so itself.) The cousin refused because she knew Jones would be jailed until a bed opened up, according to Sandy Jones. (The cousin declined an interview request.)

So Davis filed the commitment paperwork herself, writing that Sydney Jones “should be taken to DeSoto County jail” while awaiting further evaluations, a court hearing and eventual treatment.

On Sydney Jones' fourth day at Baptist-DeSoto, two sheriff's deputies arrived. They received discharge papers from a nurse and wheeled Jones out of the hospital, according to her and an incident report. Jones, who said her delusions at the time were “like if Satan made goggles and put them on you,” was terrified that the deputies would drive her to a field, rape her and kill her.

Sandy Jones said she didn't understand why she had no say in what was happening to her daughter, although that's typical during the commitment process. “I felt like she was kidnapped from me,” Sandy Jones said. Her daughter spent nine days in jail before being admitted to a crisis unit, where she was treated for about two weeks.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica interviewed five other people who were discharged from Baptist to jail, including two who had been taken to the hospital because they had attempted suicide. One said that when deputies came to his room, he wondered if he had somehow committed a crime after trying to kill himself by overdosing on prescription medication. Another said he felt humiliated to be wheeled through the hospital wearing just a hospital gown. Three of the five said they were handcuffed before being taken away.

Hospital officials noted that all patients are medically stabilized before being released and that some patients are committed by family members. Dr. H. F. Mason, Baptist-DeSoto's chief medical officer, said in an interview that he didn't know how often patients who need behavioral health treatment might be discharged to jail, but he has no concerns about the practice. When hospital staff hand patients over to local authorities, Mason said, “we feel that they're going to take the appropriate care of that patient.”

The jail, however, offers minimal psychiatric treatment, if any. Region IV staff members visit the jail primarily to evaluate people going through the commitment process or to check on people on suicide watch, Region IV Director Jason Ramey said. Jail officials said medical staff try to make sure inmates have access to their prescription drugs, although some people jailed during commitment proceedings have said they didn't consistently get their medications.

Davis and county officials involved in the commitment process said sending patients to jail as they await treatment is better than allowing them to go home, which they see as the only other option. Jail is “not ideal, but we've got to make sure these people are safe so they're not going to harm themselves or somebody else,” Davis said. “If they've had a serious suicide attempt, and they're just adamant they're going home, I mean — I can't ethically let them go home. … We do try to explore all the options before we send them there.”

Once in jail, many patients wait days or weeks to be evaluated further, to go before a judge and to be taken somewhere for treatment, according to a review of jail dockets. One 37-year-old man picked up at Baptist-DeSoto in 2022 was jailed for nearly two months, which according to jail dockets was one of the longest detentions between 2021 and 2023.

The husband of a 64-year-old woman said that during the evaluation process he was encouraged by someone at Baptist-DeSoto — he doesn't remember who — to pursue commitment proceedings after his wife stopped taking her bipolar disorder medication and overdosed on prescription drugs and alcohol. She was jailed for 28 days.

“I'm a Jehovah's Witness,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified because she doesn't want people to know she was jailed for mental illness. “I never known anything like that in my life. Never been arrested. All my rights just stripped from me. To do that to an old woman, because I was having mental troubles!”

She said the experience left her terrified to seek mental health care in DeSoto County. “I'd rather die than go back in there,” she said of the jail.

DeSoto County Struggles with a Problem Other Communities Have Addressed

Although DeSoto County has long relied on its jail to house people awaiting treatment, some communities elsewhere in the state have found other options. They rely on nearby crisis units to provide short-term treatment and in many cases have arrangements with local hospitals to treat patients if a publicly funded bed isn't available.

On the Gulf Coast, people who come to hospitals in Ocean Springs or Pascagoula can be admitted to an eight-bed psychiatric unit, said Kim Henderson, director of emergency services for Singing River Health System, which operates those facilities.

Henderson said the psychiatric unit loses money because many patients lack insurance and can't pay. “It would be so much easier to say we're not going to do this anymore and shut it down,” she said. “But we don't believe that's the right thing to do.”

Over the years, DeSoto County officials have expressed frustration with how many people are jailed during the commitment process, but they've made little progress in coming up with an alternative.

In 2007, Baptist-DeSoto initiated 152 commitments, according to board meeting minutes and a news story in the DeSoto Times-Tribune; many of those patients went to jail. The hospital sends people “as quickly as they can to the Sheriff's Department. They want them out of there,” Michael Garriga, then the county administrator, said at the time, according to another Times-Tribune article. (The news stories didn't include a comment from the hospital; Alexander, Baptist's spokesperson, said she couldn't comment on practices from years ago because no one who was part of the leadership team then is still around.)

In 2008, the CEO of Parkwood Behavioral Health System, which operates a psychiatric facility in the county, offered to treat people going through the commitment process for $465 per patient per day — many times more than the $25 a day it cost back then to house someone in jail. No contract was ever signed.

Two years later, again aiming to reduce how often people awaiting mental health treatment were jailed, DeSoto County started working with a different community mental health center, Region IV. The number of people held in jail during commitment proceedings fell sharply, but within several years it had risen.

In 2021, the state Department of Mental Health said it would give Region IV money to create a crisis unit in DeSoto, the largest county in the state without one. But the county must provide the building, and it has taken about two years just to move forward with a location, according to meeting minutes.

County officials considered putting the crisis unit in a building a few miles from the hospital and even got an architect to scope out a renovation, according to meeting minutes. By 2023, those plans had been scuttled amid concerns about the cost of renovations and opposition from neighbors, according to Mark Gardner, a county supervisor, and board meeting minutes.

Former Sheriff Bill Rasco said he was told by an alderman for the city of Southaven that residents didn't want people with mental illness in their neighborhood. Rasco, who served from 2008 through 2023, said he believes the rapidly growing county has had the means to build a facility, but supervisors prioritize paving roads and keeping taxes low. “We build agricultural arenas, walking trails and ballfields, and we let our mental health suffer,” he said.

The county Board of Supervisors inched forward again in February, voting to hire an architect to draw up plans to renovate a different county building. But construction on the 16-bed facility won't start until spring 2025 at the earliest.

Gardner, who was first elected in 2011, said he has always believed that people with mental illness shouldn't be jailed, but the Sheriff's Department and Region IV didn't propose an alternative until recently. “We need it today,” he said. “I hate that we haven't been able to find a suitable place till now to put this.”

A year after Sydney Jones' second psychotic episode, she's doing better. She hasn't experienced another mental health crisis. The sight of a police cruiser no longer triggers a panic attack, though she does get anxious when she sees one in her neighborhood.

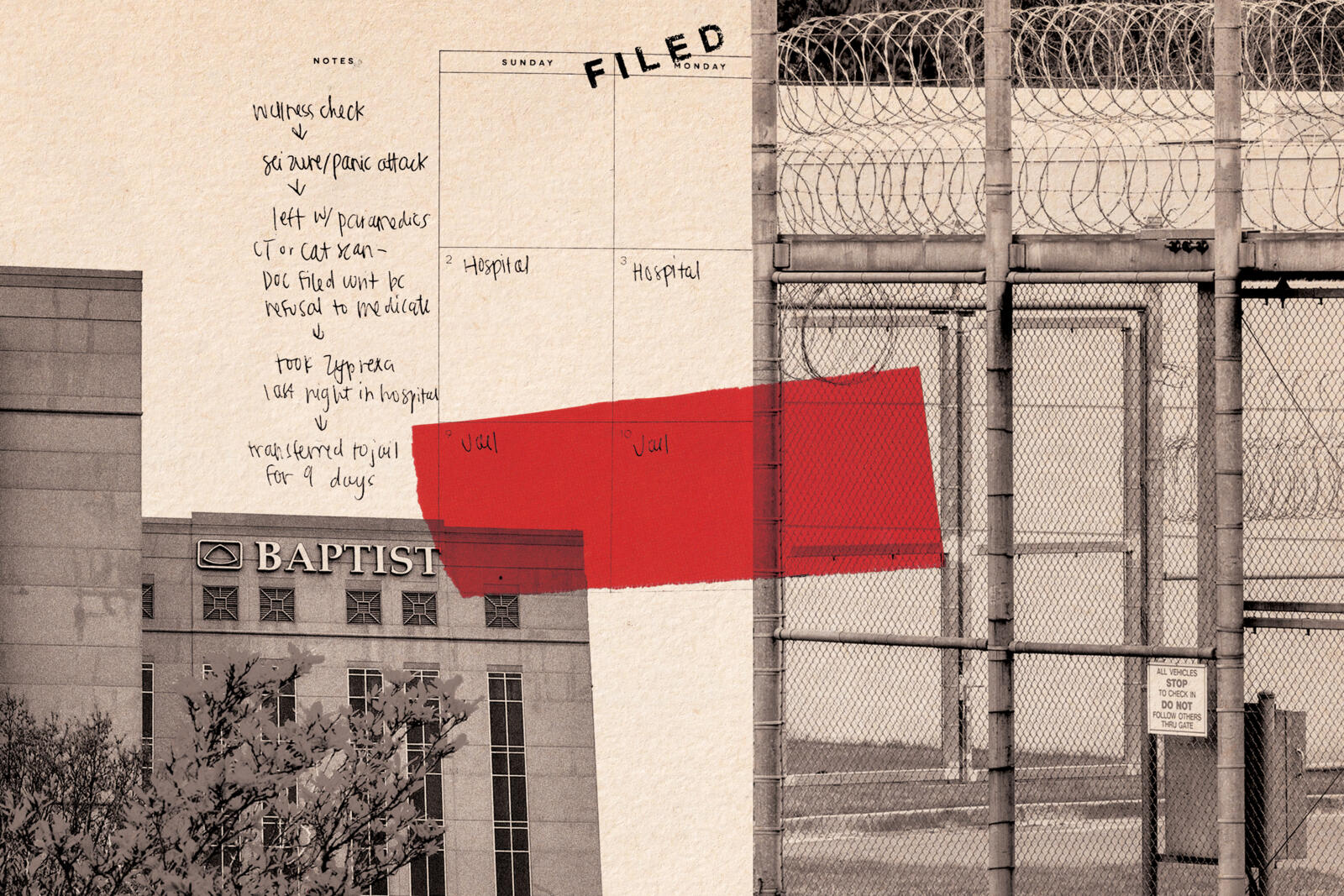

But she wants to remind herself of what she survived to get here, so she keeps mementos. The composition book where she wrote notes during group therapy at the crisis unit. The Bible she read in jail. The planner where she wrote “Hospital” in one square and “Jail” in the next. And two plastic wristbands: The white one identified her as a hospital patient; the yellow one, with her mug shot and booking number, identified her as a prisoner.

How We Reported This Story

To report this story, we obtained DeSoto County Sheriff's Department logs from 2021 through 2023 that showed when deputies were called to two local hospitals to take people into custody for involuntary commitment proceedings to receive treatment for mental illness or substance abuse. Those logs included nearly 200 calls, mostly to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto.

To determine which calls resulted in jail detentions, we needed to cross-reference the logs with incident reports and county jail dockets. We requested incident reports for about half of calls from 2021 through 2023. Although this sample wasn't collected at random, we requested records from a range of months to account for possible variations throughout the year. Patients' names were redacted from incident reports, but by using other identifying information in those reports, we matched 76% of the call logs in our sample to an entry in jail dockets. The remaining calls included not just those for which we couldn't match an incident report to a jail docket entry, but also those for which there was no incident report or the patient was taken to a crisis unit or a private psychiatric hospital.

Based on that percentage and the volume of calls during the three-year period, we estimated that about 23% of the roughly 650 people jailed during the civil commitment process in DeSoto County had been picked up at a local hospital. Again, the overwhelming majority were taken from Baptist-DeSoto. To ensure that our estimate was conservative and accounted for any variation due to our sample, we characterized this as about one-fifth of civil commitment jail detentions. We shared our preliminary findings with hospital and county officials; no one disputed them.

To determine how the number of people jailed during commitment proceedings in DeSoto County has changed over time, we obtained jail dockets dating back to 2007. We don't have data for 2009 and 2010 because of a file storage issue at the Sheriff's Department.

Agnel Philip of ProPublica contributed reporting. Mollie Simon of ProPublica contributed research.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=362139

-

SuperTalk FM3 days ago

Mississippi businessman accused of working with mafia boss in fraud scheme pleads guilty

-

Mississippi News4 days ago

Mississippi trooper hit by vehicle while conducting checkpoint

-

Kaiser Health News7 days ago

California Pays Meth Users To Get Sober

-

SuperTalk FM7 days ago

Authorities investigating two separate inmate deaths in Mississippi

-

Mississippi News7 days ago

Chancery Court Judge Joseph Kilgore leaving public office

-

Local News Video2 days ago

Mental Health Awareness Month: Addiction and your mental health

-

Mississippi News3 days ago

Gym for children with special needs opens in Tupelo

-

Mississippi News5 days ago

Second body found this year