Mississippi Today

What exactly is Gov. Tate Reeves’ involvement in the welfare scandal?

Whether Gov. Tate Reeves was involved in the multimillion dollar welfare scandal has emerged as one of the top issues of the 2023 campaign for governor — and Mississippians across the state are being deluged with advertisements and attacks about it.

Brandon Presley, the Democrat running for governor against Reeves in November, has anchored his candidacy on the scandal, in which at least $77 million in federal funds intended for the state's poorest residents were misspent or directed to wealthy, politically-connected Mississippians between at least 2017 and 2020.

For weeks, Presley has blanketed the state with a TV advertisement alleging: “Under Tate Reeves, millions were steered from education and job programs to help his rich friends.”

Reeves, the first-term Republican, has strongly denied any wrongdoing related to the scandal. After Presley began airing the TV ad, Reeves quickly responded with his own ad that counters Presley's claim.

“Tate Reeves had nothing to do with the scandal,” the Reeves ad narrator says. “… It all happened before he was governor.”

Just last week, Presley held a press conference outside the welfare agency office building to reiterate his attacks against Reeves for his involvement in the scandal. And Reeves, who as governor is leading the state's civil lawsuit and ongoing investigation of the welfare scandal, has not been charged with any crime and maintains he played no role in the misspending.

So who's right? Was Reeves really involved in the scandal? Is Presley overstating Reeves' role?

Mississippi Today, which won a 2023 Pulitzer Prize for its investigation into the welfare scandal, compiled key context about Reeves' involvement.

‘The Lt. Gov's fitness issue'

When Reeves ran for his first term as governor in 2019, well-known Mississippi fitness trainer Paul Lacoste — a close personal friend of Reeves, Lacoste said at the time — endorsed him. Reeves was one of several state officials who had taken fitness boot camp classes led by Lacoste.

Today, Lacoste is one of dozens of people being sued by the state of Mississippi to recoup millions in misspent welfare funds from the time. The state's welfare department, in court documents, alleged that Lacoste improperly received $1.3 million in welfare funds.

How Lacoste received that money has been probed by investigators and in court documents, and this is where Reeves' involvement is being scrutinized.

Mississippi Today reported in its 2022 “The Backchannel” investigation that Lacoste had a 2019 meeting with Reeves, who was then the lieutenant governor, and John Davis, the former director of the Mississippi Department of Human Services who has since pleaded guilty to federal and state charges related to the scandal.

READ MORE: Gov. Tate Reeves inspired welfare payment targeted in civil suit, texts show

By 2019, Lacoste had already secured a $1.4 million contract with a well connected nonprofit to receive MSDH funds for his boot camp program. Lacoste says then-Gov. Phil Bryant directed Davis to execute the agreement. But after a few months, MDHS apparently hadn't provided the nonprofit with the funds to actually pay Lacoste. That's until Davis met with Reeves.

Two days after the 2019 scheduled meeting — which Lacoste described to Davis by saying, “Tate wants us all to himself!” — Davis texted his deputy at the welfare agency and asked him to find a way to send a large sum of federal welfare money to the nonprofit without triggering a red flag in an audit so that the nonprofit could fund Lacoste's boot camp.

Davis, in the text message, referred to the project as “the Lt. Gov's fitness issue.”

The deputy issued the payment to the nonprofit that day, according to an audit that was later used to bring criminal charges against several defendants including Davis.

When Mississippi Today asked Reeves' office about the text messages and Lacoste's receipt of federal welfare funds, a staffer replied: “It's entirely possible that — before the abuse was uncovered — Tate Reeves said nice things in passing about people he is now suing and/or the stated goals of DHS. This was all before the fraud was revealed. How is he supposed to remember inconsequential conversations from years ago?”

Reeves, as governor and statutory head of the welfare agency, is leading the state's ongoing civil lawsuit that is seeking to recoup the misspent millions. The governor's decisions about the lawsuit management has also pulled him into the spotlight.

Reeves fired attorney leading state's welfare scandal lawsuit

In 2021, the welfare agency, which is under the statutory purview of Gov. Tate Reeves' office, hired well-known attorney Brad Pigott to lead the state's effort to claw back as many of the millions in misspent welfare funds as possible.

Pigott, a former federal prosecutor who was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi by former President Bill Clinton, has a successful record with high-profile cases. In the 1980s and 90s, he led cases that took down the Dixie Mafia organized crime syndicate.

For about a year, he led the state's welfare case and brought civil charges against dozens of people who had received federal funds. But in July 2022, shortly after Pigott subpoenaed the University of Southern Mississippi Athletic Foundation for communications with former Gov. Phil Bryant, Bryant's wife Deborah, and former NFL star Brett Favre over $5 million in welfare dollars spent on a volleyball stadium, Reeves' administration abruptly fired the attorney.

Pigott said plainly that his firing was a politically motivated response to him looking into the roles of former Republican governor Bryant, the USM Athletic Foundation and other powerful and connected people or entities Reeves and others didn't want him looking at.

“All I did, and I believe all that caused me to be terminated from representing the department or having anything to do with the litigation, was to try to get the truth about all of that,” Pigott told Mississippi Today hours after his firing. “People are going to go to jail over this, at least the state should be willing to find out the truth of what happened.”

Reeves' welfare agency leader quickly said that Pigott was fired because he blind-sided them with the USM Foundation subpoena. But Mississippi Today obtained records that showed Pigott gave welfare agency leaders a 10-day heads up before he filed the subpoena in court.

READ MORE: Welfare head says surprise subpoena led to attorney's firing. Emails show it wasn't a surprise.

A few days after the story had become a full-blown scandal for Reeves, he confirmed to reporters that Pigott's firing was political in nature.

“I think the way in which (Pigott) … has acted since they chose not to renew his contract shows exactly why many of us were concerned about the way in which he conducted himself in the year in which he was employed,” Reeves said at the 2022 Neshoba County Fair. “He seemed much more focused on the political side of things. He seemed much more interested in getting his name in print and hopefully bigger and bigger print, not just Mississippi stories. He wants this to go national, wants to talk to the press.”

READ MORE: Gov. Tate Reeves says ousted welfare scandal lawyer had ‘political agenda,' wanted media spotlight

The USM Athletic Foundation is comprised of many business and political leaders, including several large donors to Reeves' campaign coffers.

To date, Reeves is still the elected official atop the state's ongoing civil lawsuit. His welfare agency has since hired attorneys at Jones Walker, a law firm that has donated thousands of dollars to his past campaigns.

Favre lobbied Reeves for USM volleyball funds

One of the largest purchases at the center of the scandal is a state-of-the-art volleyball stadium at University of Southern Mississippi, a project Favre pushed welfare officials to fund.

Asked about the stadium at Neshoba County Fair in the summer of 2022, Reeves suggested he didn't support the idea of using any taxpayer funds to build sports facilities.

At the time, Reeves' staff had opted not to include the volleyball stadium in the MDHS civil suit to claw back misspent funds — and he had just fired Pigott.

“Look, I don't know all the details as to how that came about,” Reeves said. “What I do know is that it doesn't seem like an expense that I would personally support for TANF dollars. I don't even like the state building stadiums with general tax dollars.”

But texts that wouldn't be made public until months later revealed that Reeves did talk with Favre about finding public funding to finish construction on the stadium early in his governorship, right before the February 2020 indictments. Favre had endorsed Reeves for governor in 2019.

Reeves was apparently eager to please Favre. When Favre asked Reeves to appoint a former classmate of his to the Mississippi Board of Chiropractic Examiners, the new governor readily agreed, according to texts Mississippi Today retrieved through a public records request. In the same text on Feb. 5, 2020, Favre said he and his wife Deanna wanted to show Reeves the volleyball facility “and it would only be us. I want you to see what your (sic) trying to help me for.”

“Oh Todd (Gov. Reeves' brother) said y'all may go to the concert Friday if so we may tag along and if time permits we show you facility,” Favre added.

It's unclear how hard Reeves actually pushed to include funding for the facility in a legislative appropriation, but he and his brother certainly gave Favre the impression that he would.

“He (Reeves) said he was gonna get with his team and figure something out,” Favre texted Bryant on Feb. 6, 2020, as the fallout from the arrests was still materializing.

“I think the angle Tate is looking at is a bond bill according to Todd his brother,” Favre texted Bryant on Feb. 7.

Though Mississippi Today requested them, Reeves has not produced any texts he might have exchanged with Favre or other key figures prior to January of 2020 before he became governor.

Lack of legislative oversight of welfare funds

Former Gov. Phil Bryant, who led the state's welfare department during the height of the scandal, suggested in a 2022 interview with Mississippi Today that the state Legislature, where then-Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves had an outsized leadership role, failed to meet its statutory obligation to monitor welfare agency spending.

Bryant, who has not been charged with any crime but has faced accusations of wrongdoing from numerous criminal and civil case defendants, did not name Reeves in the interview but did attempt to put the onus on legislative oversight committees.

“I didn't have the capacity to do that,” Bryant said in 2022 when asked why the misspending was not discovered earlier. “I didn't have the personnel to go and do that. That's why we depend on oversight committees from the Legislature. So, every year there was a budget that went to Human Services. Wouldn't the oversight committee of the Legislature say, ‘Okay, we want to see how your spending is going. Show us where you're spending your money. Show us all the grants that you have.' Don't they do that?”

As lieutenant governor between 2012-2020, Reeves served a pivotal leadership role in the Legislature — including during the years of 2017-2020, when the brunt of the known welfare misspending occurred.

Though Reeves was never a member of the legislative committee created by state law to provide oversight of the Department of Human Services, he has often boasted his direct control of the state budget during his time at the Capitol. Reeves served as chair or vice chair of the powerful Legislative Budget Committee that does provide oversight of agency budgets.

Bryant, in the same interview with Mississippi Today in 2022, said that legislative oversight was not fulfilled when the welfare misspending occurred. He recalled the oversight that he said used to occur during his time in the Legislature as a member of the House and later as lieutenant governor.

“But even the appropriations process,” Bryant said. “When I used to sit on the (House) Ways and Means Committee, and the joint legislative budget process, they would come in with stacks, not just Human Services, but every agency, ‘Here's my expenditures. Here's where it's going. Here's the cars that we bought.' And you could review them.

“So, no one caught that during the appropriations process, during the audit process, the attorney general, but I was supposed to catch it? None of them caught it, but I'm, being governor, and I'm supposed to catch it?”

READ MORE: Phil Bryant discusses his nephew, favored welfare vendors, failures and successes

In response to several written questions from Mississippi Today, Elliott Husbands, campaign manager for Reeves, again reiterated that Reeves played no role in the scandal and attacked Mississippi Today as being “a Democrat dark money group.” Husbands did not respond directly to what Bryant said in April 2022.

“Tate Reeves has obviously not been questioned by law enforcement because the scandal in question occurred entirely during the administration of a different governor, and the Reeves administration has worked to recoup the funds, supporting the prosecution and suing the guilty individuals,” Husbands said. “Mississippians deserve honesty, and not the lying fairy tales you publish.”

Reeves' political connections to other high-profile defendants

In a February 2020 press conference, Reeves acknowledged receiving campaign contributions from people associated with the welfare scandal and ongoing investigation, including Nancy New and her son Zach, both of whom have pleaded guilty to state and federal criminal charges. The News ran the nonprofit that funded Lacoste's contract and funneled $5 million to construct the volleyball stadium.

“I can tell you right now, anything they gave to the campaign is going to be moved to a separate bank account,” Reeves said in 2020. “… Anything they gave the campaign will be there waiting to be returned to the taxpayers and help the people it was intended for. If that doesn't happen, the money will go to a deserving charity.”

Mississippi Today and other outlets reported earlier this year, however, that there is no indication that the funds have been transferred to a separate bank account. In response to questions, the Reeves campaign gave no indication that a separate bank account had been established.

“The political donations from anyone who is connected to the TANF scandal will be donated to a worthy cause at the ultimate conclusion of the legal proceedings. Those cases are ongoing,” said Husbands, Reeves' campaign manager, referring to the continuing investigation of the misspending of $77 million in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families welfare funds.

In Reeves' 2019 gubernatorial campaign, he also filmed public education commercials touting his public school teacher pay plan at the News' now shuttered private New Summit School in Jackson. Private school students and teachers were used for the commercial.

Video from the 2019 New Summit advertisement has been used again this campaign cycle by Reeves in two commercials.

In addition to other charges and guilty pleas, federal prosecutors have alleged that Nancy New bilked the state out of $4 million in public education dollars, of which at least $76,889 that were supposed to pay for teachers at New Summit School she used to purchase a house.

READ MORE: Reeves campaign uses video from shuttered private school linked to welfare scandal

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

2024 Mississippi legislative session not good for private school voucher supporters

Despite a recent Mississippi Supreme Court ruling allowing $10 million in public money to be spent on private schools, 2024 has not been a good year for those supporting school vouchers.

School-choice supporters were hopeful during the 2024 legislative session, with new House Speaker Jason White at times indicating support for vouchers.

But the Legislature, which recently completed its session, did not pass any new voucher bills. In fact, it placed tighter restrictions on some of the limited laws the state has in place allowing public money to be spent on private schools.

Notably, the Legislature passed a bill that provides significantly more oversight of a program that provides a limited number of scholarships or vouchers for special-needs children to attend private schools.

Going forward, thanks to the new law, to receive the vouchers a parent must certify that their child will be attending a private school that offers the special needs educational services that will help the child. And the school must report information on the academic progress of the child receiving the funds.

Also, efforts to expand another state program that provides tax credits for the benefit of private schools was defeated. Legislation that would have expanded the tax credits offered by the Children's Promise Act from $8 million a year to $24 million to benefit private schools was defeated. Private schools are supposed to educate low income students and students with special needs to receive the benefit of the tax credits. The legislation expanding the Children's Promise Act was defeated after it was reported that no state agency knew how many students who fit into the categories of poverty and other specific needs were being educated in the schools receiving funds through the tax credits.

Interestingly, the Legislature did not expand the Children's Promise Act but also did not place more oversight on the private schools receiving the tax credit funds.

The bright spot for those supporting vouchers was the early May state Supreme Court ruling. But, in reality, the Supreme Court ruling was not as good for supporters of vouchers as it might appear on the surface.

The Supreme Court did not say in the ruling whether school vouchers are constitutional. Instead, the state's highest court ruled that the group that brought the lawsuit – Parents for Public Schools – did not have standing to pursue the legal action.

The Supreme Court justices did not give any indication that they were ready to say they were going to ignore the Mississippi Constitution's plain language that prohibits public funds from being provided “to any school that at the time of receiving such appropriation is not conducted as a free school.”

In addition to finding Parents for Public Schools did not have standing to bring the lawsuit, the court said another key reason for its ruling was the fact that the funds the private schools were receiving were federal, not state funds. The public funds at the center of the lawsuit were federal COVID-19 relief dollars.

Right or wrong, The court appeared to make a distinction between federal money and state general funds. And in reality, the circumstances are unique in that seldom does the state receive federal money with so few strings attached that it can be awarded to private schools.

The majority opinion written by Northern District Supreme Justice Robert Chamberlin and joined by six justices states, “These specific federal funds were never earmarked by either the federal government or the state for educational purposes, have not been commingled with state education funds, are not for educational purposes and therefore cannot be said to have harmed PPS (Parents for Public Schools) by taking finite government educational funding away from public schools.”

And Southern District Supreme Court Justice Dawn Beam, who joined the majority opinion, wrote separately “ to reiterate that we are not ruling on state funds but American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds … The ARPA funds were given to the state to be used in four possible ways, three of which were directly related to the COVID -19 health emergency and one of which was to make necessary investments in water, sewer or broadband infrastructure.”

Granted, many public school advocates lamented the decision, pointing out that federal funds are indeed public or taxpayer money and those federal funds could have been used to help struggling public schools.

Two justices – James Kitchens and Leslie King, both of the Central District, agreed with that argument.

But, importantly, a decidedly conservative-leaning Mississippi Supreme Court stopped far short – at least for the time being – of circumventing state constitutional language that plainly states that public funds are not to go to private schools.

And a decidedly conservative Mississippi Legislature chose not to expand voucher programs during the 2024 session.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

On this day in 1925

MAY 19, 1925

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska. When he was 14, a teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up and he answered that he wanted to be a lawyer. The teacher chided him, urging him to be realistic. “Why don't you plan on carpentry?”

In prison, he became a follower of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. In his speeches, Malcolm X warned Black Americans against self-loathing: “Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair? Who taught you to hate the color of your skin? Who taught you to hate the shape of your nose and the shape of your lips? Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet? Who taught you to hate your own kind?”

Prior to a 1964 pilgrimage to Mecca, he split with Elijah Muhammad. As a result of that trip, Malcolm X began to accept followers of all races. In 1965, he was assassinated. Denzel Washington was nominated for an Oscar for his portrayal of the civil rights leader in Spike Lee's 1992 award-winning film.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=359877

Mississippi Today

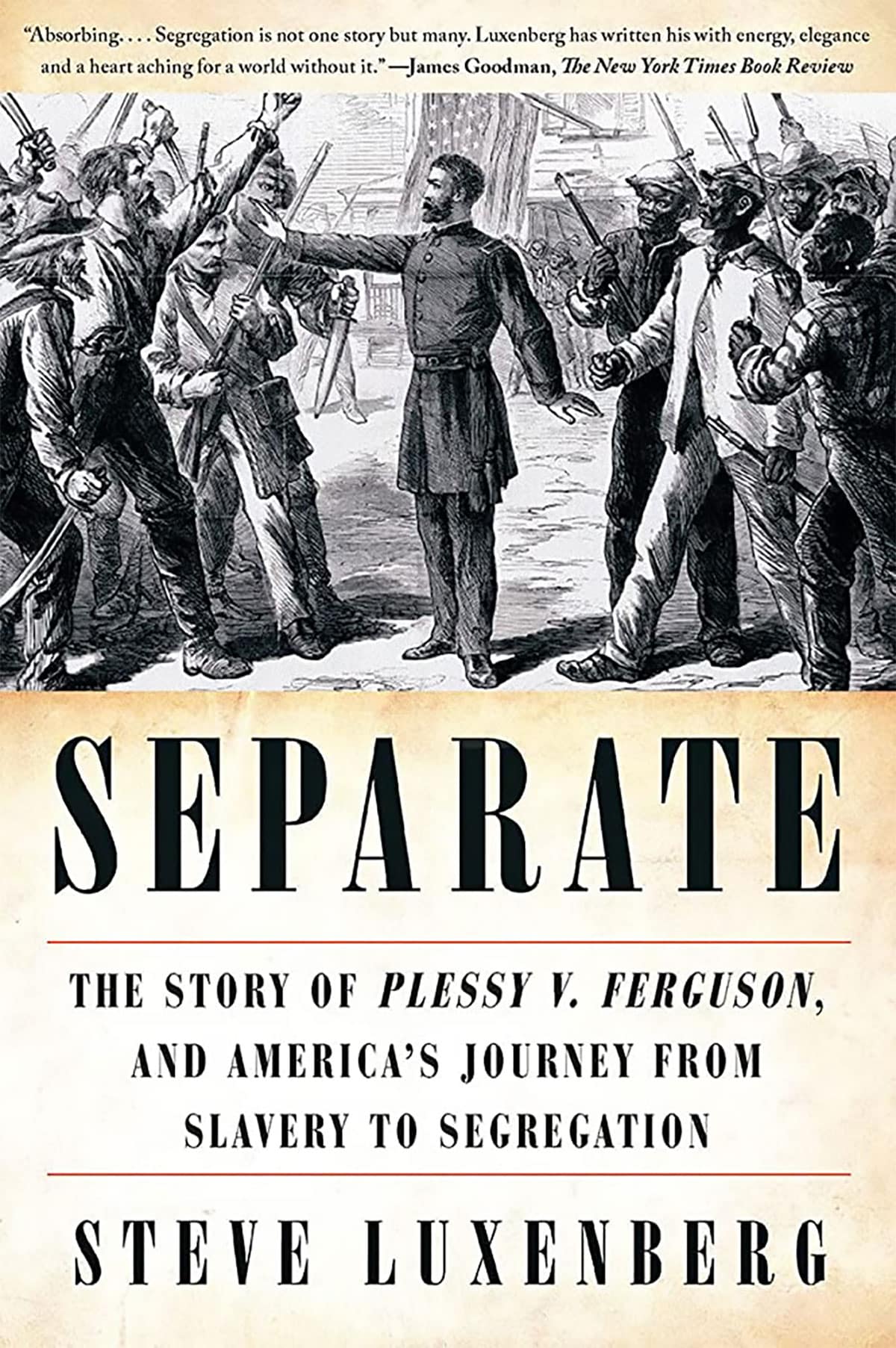

On this day in 1896

MAY 18, 1896

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-1 in Plessy v. Ferguson that racial segregation on railroads or similar public places was constitutional, forging the “separate but equal” doctrine that remained in place until 1954.

In his dissent that would foreshadow the ruling six decades later in Brown v. Board of Education, Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote that “separate but equal” rail cars were aimed at discriminating against Black Americans.

“In the view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens,” he wrote. “Our Constitution in color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful. The law … takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=359301

-

SuperTalk FM7 days ago

Martin Lawrence making 3 stops in Mississippi on comedy tour

-

Our Mississippi Home6 days ago

Beat the Heat with Mississippi’s Best Waterparks

-

SuperTalk FM3 days ago

State auditor cracking down on Mississippians receiving unemployment benefits

-

Our Mississippi Home6 days ago

Charlie’s U-Pik: Opening Soon for the Summer Season

-

Mississippi News Video5 days ago

Jackson has a gang problem

-

Kaiser Health News6 days ago

Medicaid ‘Unwinding’ Decried as Biased Against Disabled People

-

Local News2 days ago

Family files lawsuit after teen’s suicide in Harrison County Jail

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

On this day in 1950