Mississippi Today

‘So medieval’: Man with mental illness jailed for 20 days without charges

In January, the head of Mississippi’s Department of Mental Health told lawmakers that people who aren’t charged with a crime are spending less time in jail than they used to: The average wait time for a state hospital bed was down to three days after a court hearing.

At that moment, a young man was on his 16th day locked in the DeSoto County Jail with no criminal charges. He was waiting for mental health treatment.

His mother, Sarah, was still trying to understand why he was there at all.

David, 29, was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder about a decade ago. Since then, he has cycled through hospital stays and group homes. Sarah can rattle off the low points. There was the time her son was walking in the street and got hit by a car and broke his neck. And the time he called her from a Megabus in Texas, nearly at the border with Mexico.

But this was something new: a three-week detention that began after he called 911 seeking treatment and eventually wound up jailed at the request of his providers.

Her son’s treatment in DeSoto County – where a county website still uses the phrase “lunacy” hearings to refer to the proceedings where judges order people like David to receive psychiatric treatment – reminded Sarah of a different era.

“When they, you know, lock them in the dungeon or whatever and put chains on them and just let them live the rest of their lives there,” she said. “This is so medieval, what they’re doing.”

In the end, David was jailed for a total of three weeks before being transported to North Mississippi State Hospital at the end of January. Mississippi Today is not using his or his family’s real names to protect his privacy.

It is far from unusual in Mississippi and particularly in DeSoto County for people to be jailed solely because they are awaiting treatment through the state’s involuntary commitment process. No other state jails so many people for such lengths of time, solely on the basis of mental illness. Mississippi Today and ProPublica previously reported that hundreds of people are jailed without criminal charges every year while they await evaluations and treatment through the involuntary commitment process.

From 2019 through 2022, DeSoto County jailed people without criminal charges just under 500 times, more than any other county in the news organizations’ analysis.

As lawmakers debate changing Mississippi’s commitment laws to reduce jail detentions, David’s path through the state’s mental health system shows how it can funnel a sick person into jail, and how long it can take for them to get out once locked up.

A publicly funded facility established to treat people in crisis sent David to jail. Though the Department of Mental Health says commitment hearings should take place within 10 days, county officials instead kept him locked up for 14 days before he saw a judge, as winter weather shut down the county court system. The state hospital where the judge ordered him to receive treatment would not admit him for six more days – all of which he spent in jail.

The county is working on opening a crisis center to treat people suffering mental health crises – and keep them out of jail during the commitment process – and supervisors recently voted to hire an architect to draw up renovation plans for the county building that will house the center. The county is currently the largest in the state without one.

County administrator Vanessa Lynchard noted that reforming the commitment process is a priority for the Legislature this year, and that could hopefully bring some relief.

“Nobody likes mental commitments in the jail,” she said.

But officials involved in the process say jail is sometimes the only place they have to detain people during the commitment process, and that jailing people is safer than sending them home. And so every year, the county jails well over 100 people solely because they may be mentally ill – including people like David.

‘He really wants to live a normal life’

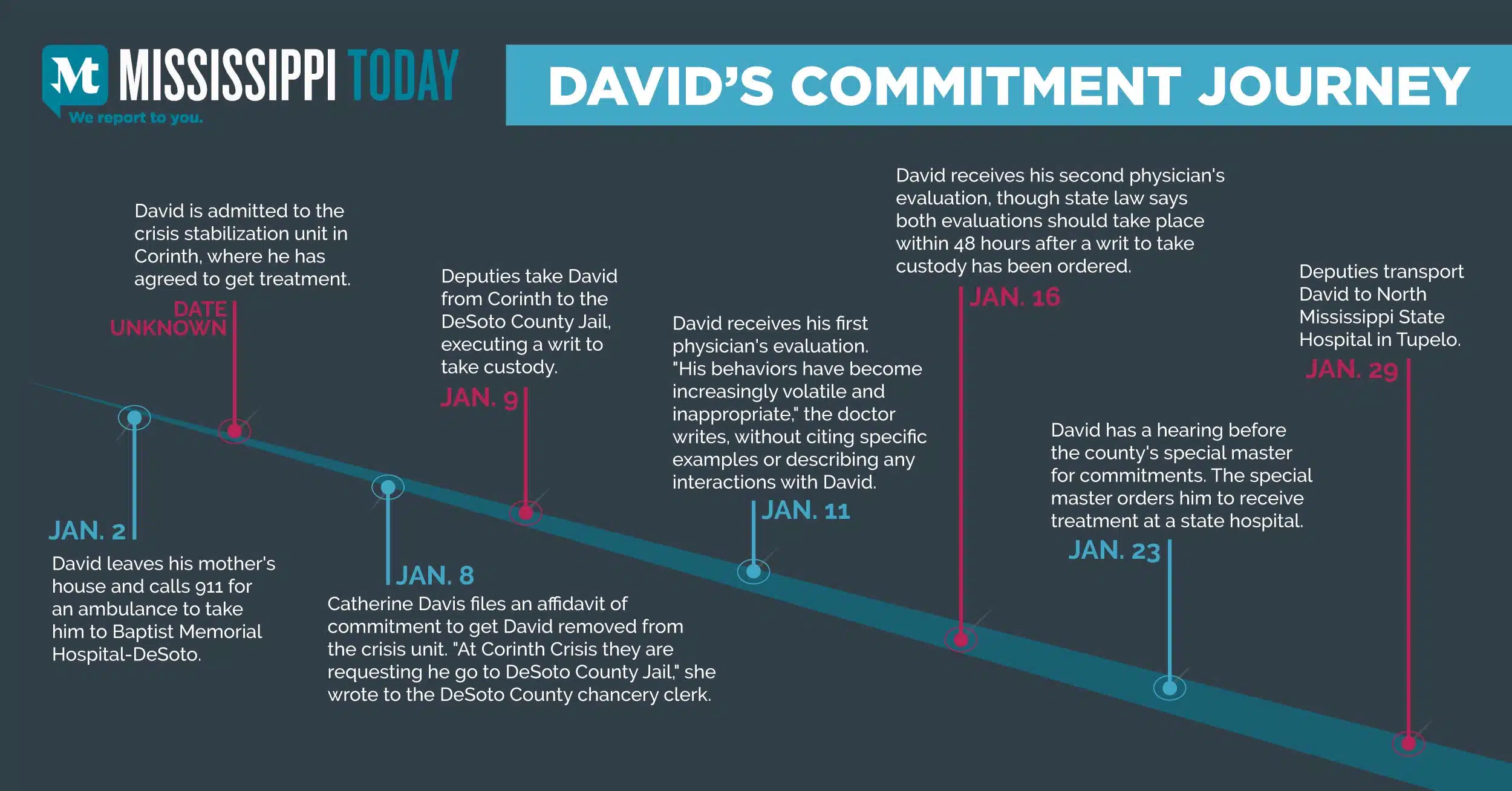

In early January, David walked away from his mother’s home in a tidy subdivision in DeSoto County. He knocked on a neighbor’s door and used the phone to call 911 for an ambulance to take him to the hospital.

When Sarah found out he was at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, she decided to let him stay there and get treatment. That he had been able to get himself there was a sign of progress. When his mental illness became severe about 10 years ago, “he used to just let himself spin out of control,” Sarah said.

When David was a teenager, he developed phobias that his mother found strange. He stopped wanting to go to school, claiming his breath smelled bad. After he ran away from home, he was hospitalized at Lakeside, a psychiatric hospital in Memphis.

He graduated from high school and got a job working at a warehouse, riding his bicycle more than an hour each way to arrive by 5 or 6 o’clock in the morning.

Then, when he was about 19, “stuff went totally to the left with him,” his mother said. He would disappear from home for days at a time. If he wound up at a hospital, staff wouldn’t tell her he was there, citing patient privacy protections. At home, he would refuse to take medications.

A few years ago, Sarah spent $2,500 to go through the legal process to gain conservatorship over her son so that she would always be included in conversations about his treatment.

“When the dust settles and the smoke clears, he always comes back to me,” she said. “If you’ve got him and put him on the wrong medication and overmedicated him, then I’ve got to help him get back on track.”

David belongs to a tight-knit family: He has siblings, a doting grandfather, aunts and uncles. Sarah’s phone is full of pictures of her son. There’s a shot of him getting his face painted at a family party and another of him wearing a Mickey Mouse t-shirt at Disneyland. A video shows him chasing his sister’s kids around his mother’s backyard.

His family tries to help him manage his symptoms. When he lived with his older sister Beth recently, he would go into the backyard to pace and talk to himself.

“I’d go out there like every 15 minutes, like, ‘Hey, you’re too loud, you need to calm down,’ but I don’t interrupt,” she said. “That’s his way of calming himself down.”

David has told his sister that he doesn’t like depending on her and their mom, that he feels bad he doesn’t drive or hold a job – something that has been a goal for years.

“He’ll tell you that he really wants to live a normal life,” Beth said.

From the crisis unit to a jail cell

One day in January, after a few days at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, David was transported to a crisis stabilization unit in Corinth, where he had agreed to get treatment. Operated by the community mental health center Region IV, which serves residents of DeSoto and four other counties, the facility is one of more than a dozen around the state designed to serve people closer to their homes, ideally keeping them out of the state hospitals – and out of jail.

For David, the crisis unit did the opposite.

Sarah sent over her conservatorship paperwork so she could be updated about his treatment. She expected to hear from her son not long after he arrived there, because he always calls her once he feels more like himself. When that didn’t happen, she called the crisis unit.

“He’s in the DeSoto County Jail,” staff told her.

Documents filed with the DeSoto County Chancery Court and reviewed by Mississippi Today show that after refusing medications twice, David had taken them and said he thought it was helping. There were no indications of violence or physical aggression. But not long after he arrived, staff requested a writ – a document allowing the sheriff’s department to take custody of a patient – because of his “agitation and inappropriate sexual conduct.”

Staff reported that he was experiencing “Psychosis including delusions, irritability. He is continually masterbating (sic).” They wrote that he had masturbated in front of other patients and a staff member.

It’s not clear from the documents exactly how long David was at the crisis unit before staff requested the writ, and Sarah said she was not contacted when he arrived there. It may have been as little as a day or two: The court order committing him says he arrived at Corinth “on or about 01/08/24.”

On Jan. 8, Catherine Davis, crisis coordinator at Region IV, which runs the crisis center, wrote: “At Corinth Crisis they are requesting he go to DeSoto County Jail.”

The next afternoon, deputies arrived to take David into custody and drive him 90 minutes back to DeSoto County. He was booked into the county jail with his charge listed as “Writ to take custody.”

Psychiatrists told Mississippi Today that people with David’s condition may exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior like public masturbation, stepping from hypersexuality and impulsivity that can be symptoms of mania.

“All they want to focus on is what he was doing wrong there,” Sarah said. “I understand that. But that’s because he needs psychiatric treatment. He’s mentally unstable. You’re a crisis center. Isn’t that what you do? But instead you ship him off to jail.”

Jason Ramey, executive director of Region IV, the community mental health center that runs the crisis unit, said he can’t discuss a specific client, citing HIPAA.

“At no point in time is it our goal to have somebody sitting in jail, but we also have to think about the wellbeing of the whole CSU, whether it’s the other clients there and things like that,” he said.

Ramey said that in 2023, the crisis unit staff initiated commitment proceedings on only three patients. The facility treated nearly 300 people in the most recent fiscal year.

“We want them to continue to receive treatment,” he said of patients awaiting transfer to a different facility. “If we’re not able to provide that, we want to get them to the state hospital as quickly as possible. It’s not like we file a writ just to have them go sit in jail.”

But in David’s case, that’s exactly what happened.

Dr. Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia and former president of the American Psychiatric Association, reviewed the commitment paperwork and initial evaluation filed with the chancery court in David’s case. He said sending David to jail was wrong.

“The sexually inappropriate behavior is a function of his current acute psychosis, and so the proper response to it is to treat the psychosis, which doesn’t happen overnight,” he said.

Dr. Marvin Swartz, a professor of psychiatry at Duke University, said it may have been appropriate to transfer David to another facility, but that elsewhere in the United States, such a transfer would not involve waiting in jail.

Dr. Lauren Stossel, a forensic psychiatrist and former chief of mental health for New York City jails, said that mental health providers have a responsibility to transfer patients to a higher level of care if they can’t provide safe and effective treatment.

Mississippi’s practice of routinely jailing people without criminal charges while they await psychiatric treatment demands systemic change, she said. But in the meantime, crisis center staff shouldn’t avoid commitment at all costs.

“Clinicians need to consider all their patients and staff and make a decision about what they can manage in their facility,” she said. “The fact that jail is a possible alternative is appalling and needs to be factored in, but they also have to be careful about getting in over their heads trying to manage patients they have no way of treating safely or effectively.”

When reviewing the information crisis center staff provided to the chancery court to justify their decision to initiate commitment proceedings, however, Stossel didn’t see a clear explanation of what staff believed the patient needed that they weren’t equipped to provide.

“It’s not clear to me based on this information: what symptoms or behaviors is this patient exhibiting that you can’t manage? What interventions have you already tried? How long did you allow him to respond to treatment before determining a higher level of care was necessary? It’s crucial to require a clear justification to protect the patient from an unnecessarily restrictive outcome.”

Adam Moore, spokesman for the Department of Mental Health, which funds the crisis units, did not answer specific questions about what happened to David. He said in an email statement that a crisis unit may initiate commitment proceedings when their clinical staff feels that someone served there meets commitment criteria or is in need of a higher level of care.

‘I didn’t know I was gonna get sent to jail’

While her son was in jail, Sarah wondered what medications he was taking, concerned that any disruption could worsen his symptoms. She and her daughter, Beth, worried about what he might experience as a young Black man locked up – with no criminal charges – in a Mississippi county jail. They prayed for God to keep him safe.

Sarah called the jail every day to find out how David was doing. During one of those calls, on Jan. 22, a staffer at the jail told her David would have a hearing in court the next day.

It had been 14 days since he was jailed, and 15 since the affidavit requesting his commitment was filed. The Department of Mental Health publishes guidelines saying that the entire process should wrap up within 10 days, but it doesn’t track whether that actually happens.

Special master Adam Emerson, the attorney appointed by a chancellor to preside over commitment hearings, said the county normally holds commitment hearings every Thursday, and sometimes on Tuesdays as well to meet the statutory deadline. Most hearings take place within a week of the writ being served, he said.

He would not comment on David’s case because it is his policy not to discuss specific commitment proceedings, but said that the week of Jan. 15, the entire county court system was shut down due to winter weather, postponing all hearings to the following week.

Emerson said he serves as special master as a way to serve the community where he has lived for nearly his entire life. During a decade as a public defender in the county, he realized many of his clients had mental health or addiction issues that led to criminal charges.

“I continue to believe that early intervention in situations where mental health issues are involved will lead to better outcomes to the individuals and society at large,” he wrote in an email to Mississippi Today.

To make it to the hearing, Sarah had to take the day off of work. At the courthouse in Hernando, she sat in the hallway with three other families of people going through the commitment process.

Eventually, she was called into the courtroom and took a seat in the front row. Deputies escorted her son into the room. He was shackled, with his hands chained to his waist and another chain running down to his feet.

Sarah noticed that almost everyone else in the courtroom was white. She suspected that racism had played a role in her son’s treatment. He is 6-foot-7, and though she knows him as “a gentle giant” who acts like one of her grandchildren, she worries other people are scared of him.

“It’s three strikes against you right there,” she said. “You’re African-American– strike one. African-American male– strike two. Then you’re an African-American male with a mental health disease. You just struck out.”

Emerson said he could not speak to David’s treatment outside of his courtroom, but that race had not played a role in his decision.

“I can only tell you that everyone who comes before my court is treated equally and with dignity and respect,” he said. “A person’s race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual preference, etc. is never a factor in our decisions.”

Mississippi Today reviewed the recording of the hearing after filing a motion to unseal it, with a letter of support from Sarah.

At the beginning of the 10-minute hearing, Catherine Davis, the Region IV crisis coordinator who had filed the affidavit against David, explained why she believed commitment was necessary.

Davis said that David had been masturbating at the crisis center, and that he was “hostile,” without saying what that meant exactly.

“When he was redirected he was becoming hostile,” Davis said. “He was pacing, responding to internal stimuli. So they felt at that point he wasn’t safe with the staff and the other clients. So they asked us to do a court commitment.”

When it was his turn to speak, David offered a different account of how he reacted to instructions from staff.

“After they told me the first time, I stopped,” he said, forming his sentences slowly and softly. “I really didn’t know it was a problem. I didn’t know I was gonna get sent to jail. I was just trying to get to the hospital.”

He told the judge he didn’t need more treatment.

Emerson called on Sarah to speak as well. She described the frustration and stress of sending her conservatorship paperwork to the crisis center only to learn days later her son had been taken to jail with no one informing her.

“I have been left out of this the entire time, and I don’t understand why,” she said.

On the recommendation of Davis and two physicians, Emerson ordered David into treatment at a state hospital.

“I’m doing that for your own good, to try to get you stabilized and get you back out,” he said to David.

To Sarah, he added: “Certainly based on where he’s sent, if I were you I’d try to get those records down to them so maybe they can keep you in the loop, OK?”

Before she could talk to or hug her son, Sarah was ushered out of the courtroom. David went back to jail for six more days.

‘How does being incarcerated support one’s mental health?’

On Jan. 29, 20 days after he was first jailed, David was transported to North Mississippi State Hospital.

Moore, the Department of Mental Health spokesman, said that the wait time information the agency had shared with lawmakers was an average and that it does not include any time a person is jailed before their hearing.

“Any individual’s wait time may be more or less than the average wait time for all admissions from a given period of time,” he wrote.

By early April, David was still at the state hospital in Tupelo. When Sarah visited him, she was disturbed that he had little energy, which she attributes to his long list of medications prescribed by the hospital staff. He told her he’s ready to come home, and he talked about trying to get a job.

His mother filed a complaint with the Mississippi Department of Health and with the Attorney General’s Public Integrity Division, which is responsible for prosecuting cases involving the exploitation of vulnerable adults.

She also emailed Wendy Bailey, head of the Department of Mental Health.

“As I deal with DeSoto County, which happens to be one of the fastest growing counties in the state, I am appalled at their antiquated systems of mental health support,” she wrote.

“How does being incarcerated support one’s mental health? What immediate changes can be made to improve upon this system?”

Bailey connected Sarah with Falisha Stewart, director of the Office of Consumer Supports. Stewart said there had been a communication “breakdown” when the Corinth crisis stabilization unit failed to contact Sarah about her son’s transfer to jail. She said the agency had enacted a plan to prevent communication lapses from happening in the future.

“It is unfortunate individuals who deal with mental health issues have to wait in jails for an available bed while being committed,” Stewart wrote. “These laws can only change through the process of speaking with your state representatives.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

Mississippi hospitals could lose up to $1 billion over the next decade under the sweeping, multitrillion-dollar tax and policy bill President Donald Trump signed into law last week, according to leaders at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

The leaders say the cuts could force some already-struggling rural hospitals to reduce services or close their doors.

The law includes the largest reduction in federal health and social safety net programs in history. It passed 218-214, with all Democrats voting against the measure and all but five Republicans voting for it.

In the short term, these cuts will make health care less accessible to poor Mississippians by making the eligibility requirements for Medicaid insurance stiffer, likely increasing people’s medical debt.

In the long run, the cuts could lead to worsening chronic health conditions such as diabetes and obesity for which Mississippi already leads the nation, and making private insurance more expensive for many people, experts say.

“We’ve got about a billion dollars that are potentially hanging in the balance over the next 10 years,” Mississippi Hospital Association President Richard Roberson said Wednesday during a panel discussion at his organization’s headquarters.

“If folks were being honest, the entire system depends on those rural hospitals,” he said.

Mississippi’s uninsured population could increase by 160,000 people as a combined result of the new law and the expiration of Biden-era enhanced subsidies that made marketplace insurance affordable – and which Trump is not expected to renew – according to KFF, a health policy research group.

That could make things even worse for those who are left on the marketplace plans.

“Younger, healthier people are going to leave the risk pool, and that’s going to mean it’s more expensive to insure the patients that remain,” said Lucy Dagneau, senior director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society.

Among the biggest changes facing Medicaid-eligible patients are stiffer eligibility requirements, including proof of work. The new law requires able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to work, do community service or attend an educational program at least 80 hours a month to qualify for, or keep, Medicaid coverage and federal food aid.

Opponents say qualified recipients could be stripped of benefits if they lose a job or fail to complete paperwork attesting to their time commitment.

Georgia became the case study for work requirements with a program called Pathways to Coverage, which was touted as a conservative alternative to Medicaid expansion.

Ironically, the 54-year-old mechanic chosen by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to be the face of the program got so fed up with the work requirements he went from praising the program on television to saying “I’m done with it” after his benefits were allegedly cancelled twice due to red tape.

Roberson sent several letters to Mississippi’s congressional members in weeks leading up to the final vote on the sweeping federal legislation, sounding the alarm on what it would mean for hospitals and patients.

Among Roberson’s chief concerns is a change in the mechanism called state directed payments, which allows states to beef up Medicaid reimbursement rates – typically the lowest among insurance payors. The new law will reduce those enhanced rates to nearly as low as the Medicare rate, costing the state at least $500 million and putting rural hospitals in a bind, Roberson told Mississippi Today.

That change will happen over 10 years starting in 2028. That, in conjunction with the new law’s one-time payment program called the Rural Health Care Fund, means if the next few years look normal, it doesn’t mean Mississippi is safe, stakeholders warn.

“We’re going to have a sort of deceiving situation in Mississippi where we look a little flush with cash with the rural fund and the state directed payments in 2027 and 2028, and then all of a sudden our state directed payments start going down and that fund ends and then we’re going to start dipping,” said Leah Rupp Smith, vice president for policy and advocacy at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

Even with that buffer time, immediate changes are on the horizon for health care in Mississippi because of fear and uncertainty around ever-changing rules.

“Hospitals can’t budget when we have these one-off programs that start and stop and the rules change – and there’s a cost to administering a program like this,” Smith said.

Since hospitals are major employers – and they also provide a sense of safety for incoming businesses – their closure, especially in rural areas, affects not just patients but local economies and communities.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson is the only Democrat in Mississippi’s congressional delegation. He voted against the bill, while the state’s two Republican senators and three Republican House members voted for it. Thompson said in a statement that the new law does not bode well for the Delta, one of the poorest regions in the U.S.

“For my district, this means closed hospitals, nursing homes, families struggling to afford groceries, and educational opportunities deferred,” Thompson said. “Republicans’ priorities are very simple: tax cuts for (the) wealthy and nothing for the people who make this country work.”

While still colloquially referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name was changed by Democrats invoking a maneuver that has been used by lawmakers in both chambers to oppose a bill on principle.

“Democrats are forcing Republicans to delete their farcical bill name,” Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer of New York said in a statement. “Nothing about this bill is beautiful — it’s a betrayal to American families and it’s undeserving of such a stupid name.”

The law is expected to add at least $3.3 trillion to the nation’s debt over the next 10 years, according to the most recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article reports on the negative impacts of a major federal tax and policy bill on Medicaid funding and rural hospitals in Mississippi. While it presents factual details and statements from stakeholders, the tone and framing emphasize the harmful consequences for vulnerable populations and health care access, aligning with concerns typically raised by center-left perspectives. The article highlights opposition by Democrats and critiques the bill’s priorities, particularly its effect on poor and rural communities, suggesting sympathy toward social safety net preservation. However, it maintains mostly factual reporting without overt partisan language, resulting in a moderate center-left bias.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

Woman arrested in Morgantown McDonald’s parking lot

-

The Center Square7 days ago

Alcohol limits at odds in upcoming dietary guidelines | National

-

The Center Square5 days ago

Here are the violent criminals Judge Murphy tried to block from deportation | Massachusetts

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Hill Country flooding: Here’s how to give and receive help

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Raleigh caps Independence Day with fireworks show outside Lenovo Center

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

The Other Passionflower | Our Mississippi Home

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Shannon County Sheriff alleges ‘orchestrated campaign of harassment and smear tactics,’ threats to life