ESA/Proba-3/ASPIICS/WOW algorithm, CC BY-SA

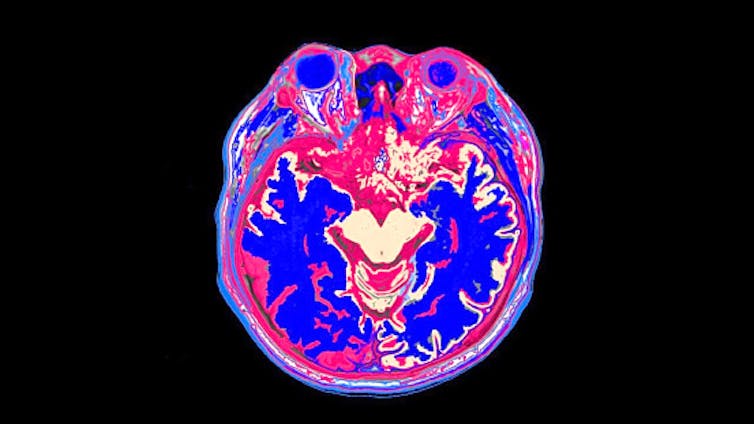

During a solar eclipse, astronomers who study heliophysics are able to study the Sun’s corona – its outer atmosphere – in ways they are unable to do at any other time.

The brightest part of the Sun is so bright that it blocks the faint light from the corona, so it is invisible to most of the instruments astronomers use. The exception is when the Moon blocks the Sun, casting a shadow on the Earth during an eclipse. But as an astronomer, I know eclipses are rare, they last only a few minutes, and they are visible only on narrow paths across the Earth. So, researchers have to work hard to get their equipment to the right place to capture these short, infrequent events.

In their quest to learn more about the Sun, scientists at the European Space Agency have built and launched a new probe designed specifically to create artificial eclipses.

Meet Proba-3

This probe, called Proba-3, works just like a real solar eclipse. One spacecraft, which is roughly circular when viewed from the front, orbits closer to the Sun, and its job is to block the bright parts of the Sun, acting as the Moon would in a real eclipse. It casts a shadow on a second probe that has a camera capable of photographing the resulting artificial eclipse.

ESA-P. Carril, CC BY-NC-ND

Having two separate spacecraft flying independently but in such a way that one casts a shadow on the other is a challenging task. But future missions depend on scientists figuring out how to make this precision choreography technology work, and so Proba-3 is a test.

This technology is helping to pave the way for future missions that could include satellites that dock with and deorbit dead satellites or powerful telescopes with instruments located far from their main mirrors.

The side benefit is that researchers get to practice by taking important scientific photos of the Sun’s corona, allowing them to learn more about the Sun at the same time.

An immense challenge

The two satellites launched in 2024 and entered orbits that approach Earth as close as 372 miles (600 kilometers) – that’s about 50% farther from Earth than the International Space Station – and reach more than 37,282 miles (60,000 km) at their most distant point, about one-sixth of the way to the Moon.

During this orbit, the satellites move at speeds between 5,400 miles per hour (8,690 kilometers per hour) and 79,200 mph (127,460 kph). At their slowest, they’re still moving fast enough to go from New York City to Philadelphia in one minute.

While flying at that speed, they can control themselves automatically, without a human guiding them, and fly 492 feet (150 meters) apart – a separation that is longer than the length of a typical football stadium – while still keeping their locations aligned to about one millimeter.

They needed to maintain that precise flying pattern for hours in order to take a picture of the Sun’s corona, and they did it in June 2025.

The Proba-3 mission is also studying space weather by observing high-energy particles that the Sun ejects out into space, sometimes in the direction of the Earth. Space weather causes the aurora, also known as the northern lights, on Earth.

While the aurora is beautiful, solar storms can also harm Earth-orbiting satellites. The hope is that Proba-3 will help scientists continue learning about the Sun and better predict dangerous space weather events in time to protect sensitive satellites.

Christopher Palma, Teaching Professor of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.