Mississippi Today

Hundreds of Mississippians are jailed for mental illness every year. 5 takeaways from our reporting so far

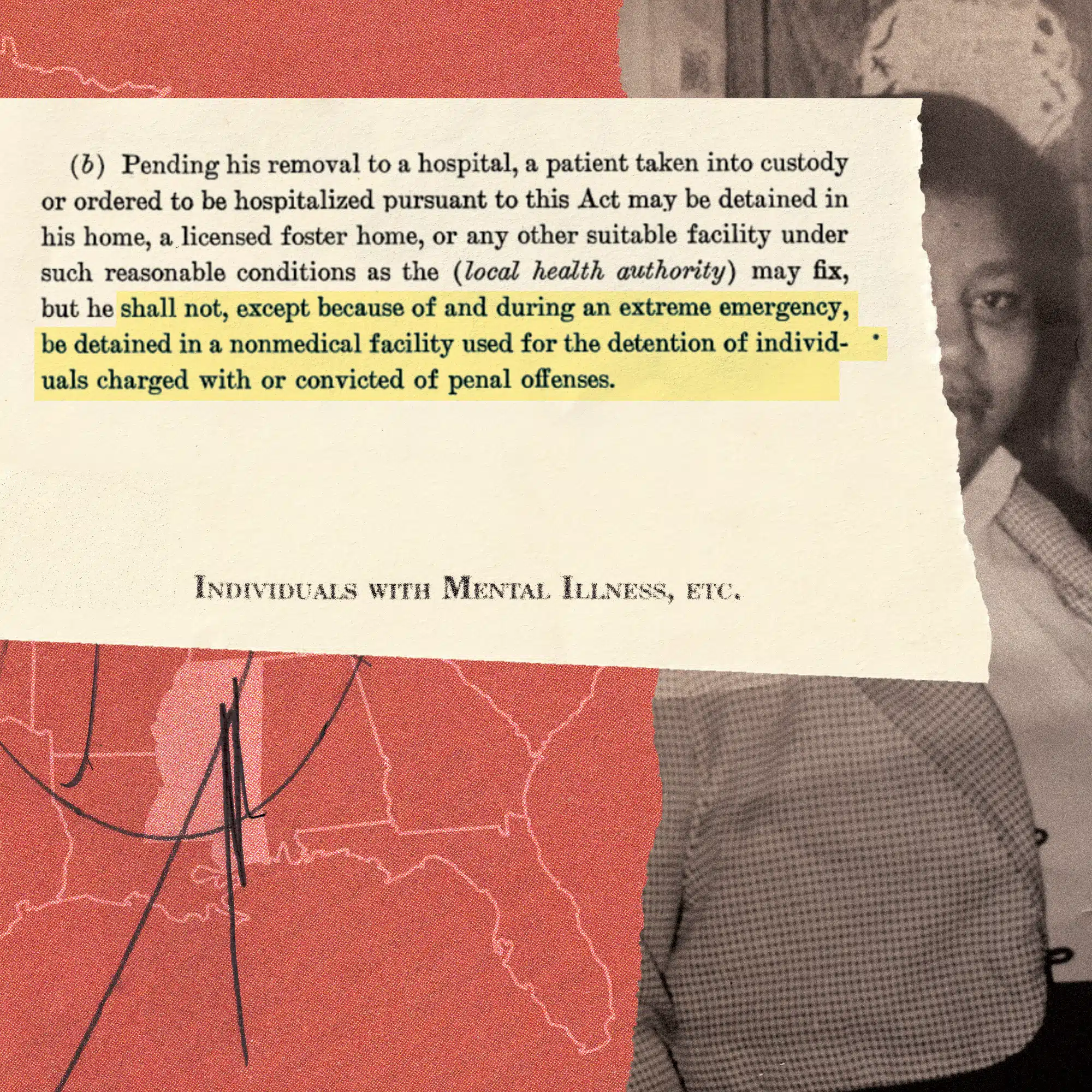

In Mississippi, the path to treatment for a serious mental illness may run through your local jail– even if you have not been charged with any crime.

In 2023, Mississippi Today and ProPublica investigated the practice of jailing people solely on the basis of possible mental illness while they wait for help through the civil commitment process.

We found that people awaiting treatment were jailed without criminal charges at least 2,000 times from 2019 to 2022 in just 19 counties, meaning the statewide figure is almost certainly higher. Most of the jail stays lasted longer than three days, and about 130 were longer than 30 days.

Some people have died after being jailed purportedly for their own safety.

Every state has a civil commitment process in which a court can order someone to be hospitalized for psychiatric treatment, generally if they are deemed dangerous to themselves or others. But it is very uncommon for people going through that process to be held in jail without criminal charges for days or weeks – except in Mississippi.

So far, we have spoken with people who were jailed solely on the basis of mental illness, family members of people who went through the process, sheriffs and jail administrators, county officials, lawmakers, the head of the Department of Mental Health and experts in mental health and disability law. We have filed more than 100 records requests and reviewed lawsuits and Mississippi Bureau of Investigation reports on jail deaths.

We plan to keep reporting. If you’d like to share your experiences or perspective, please email Isabelle Taft at itaft@mississippitoday.org or call her at (601) 691-4756.

Here are five key findings from our reporting so far:

1. People jailed solely on the basis of mental illness are generally treated the same as people accused of crimes

We spoke to more than a dozen Mississippians who were jailed without criminal charges. They wore jail scrubs and were often shackled as they moved through the jail. They were frequently unable to access prescribed psychiatric medications, much less therapy or other treatment. They had no idea how long they would be jailed, because they could get out only when a treatment bed became available. They were often housed alongside people facing criminal charges. One jail doctor told us the people going through the commitment process were vulnerable to physical assault and theft of their snacks and personal items.

“They become a prisoner just like the average person coming in that’s charged with a crime,” said Ed Hargett, a former superintendent of Parchman state penitentiary and corrections consultant who has worked with about 20 Mississippi county jails. “Some of the staff that works in the jail, they don’t really know why they’re there … Then when they start acting out, naturally they deal with them just like they would with a violent offender.”

2. Jails can be deadly for people in crisis

At least 14 people have died after being jailed during the commitment process since 2006, according to our review of lawsuits and records from the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation. Nine died by suicide, and three died following medical care that experts called substandard. Most recently, 37-year-old Lacey Handjis, a Natchez hospice-care consultant and mother of two, died in a padded cell in the Adams County Jail in late August. Her death was not by suicide and is still under investigation.

Mental health providers we spoke with said jail can exacerbate symptoms when someone is in crisis, increasing their risk of suicide. Jail staff with limited medical training may interpret signs of medical distress as manifestations of mental illness and fail to call for additional care.

After three men awaiting treatment died by suicide in the Quitman County jail in 2006, 2007 and 2019, chancery clerk Butch Scipper no longer jails people going through the commitment process. His advice to other county officials: “Do not put them in your jail. Jails are not safe places. We think they are, but they’re definitely not” for people who are mentally ill.

3. Mississippi is a stark national outlier

Mississippi Today and ProPublica surveyed disability rights advocates and state behavioral health agencies in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Nowhere else did respondents say people are routinely jailed for days or weeks without criminal charges while going through the involuntary commitment process. In three states where respondents said people are sometimes jailed to await psychiatric evaluations, it happens to fewer people and for shorter periods. At least a dozen states ban the practice altogether, while Mississippi law allows it when there is “no reasonable alternative.” In Alabama, a judge ruled it unconstitutional in 1984.

National experts and disability rights advocates in other states used words like “horrifying,” “breaks my heart” and “speechless” when they learned how many Mississippians are jailed without criminal charges while they wait for mental health care every year.

4. Despite a 2009 state law, there has been almost no oversight of jails that hold people awaiting treatment

In 2009, the legislature passed a law requiring any county facility that holds people awaiting psychiatric treatment through the commitment process to be certified by the Department of Mental Health. The department developed certification standards requiring suicide prevention training, access to medications and treatment, safe housing and more. But the law contains no funding to help counties comply and no penalties if they don’t. Only a handful of counties got certified, and after 2013 the department’s efforts to enforce the law apparently petered out.

As of late last year, only one jail – out of 71 that had recently held people awaiting court-ordered treatment – was still certified. There is no statewide oversight or inspection of county jails.

After we asked questions about the law, the Department of Mental Health sought an opinion from the Attorney General’s Office, which opined that it is a “mandatory requirement” that the agency certify the county facilities, including jails, where people wait for treatment. In October, the department sent letters to counties informing them of the ruling and encouraging them to get certified. It is waiting for counties to initiate the certification process, even though it knows exactly which jails have held people after their hearings. Department leadership, including Director Wendy Bailey, have emphasized that they have limited authority over counties and can’t force them to do anything.

5. The practice is not limited to small, entirely rural counties

According to data from the DMH, 71 of the state’s 82 counties held a total of 812 people prior to their admission to a state hospital during the year ending in June. According to state data and our analysis of jail dockets obtained through public records requests, the two counties that jail the most people during the commitment process are DeSoto and Lauderdale – together home to three of the state’s 10 largest cities. DeSoto has one of the highest per capita incomes in the state and Lauderdale’s is above average.

Meanwhile, some smaller, rural counties don’t jail people during the process or do so very rarely. Guy Nowell, who served as chancery clerk of Neshoba County until the end of 2023, said the county arranged each person’s commitment evaluations and hearing to take place on the same day to eliminate waits between appointments. If no publicly funded bed is available after the hearing, the county pays for people to receive treatment at a private psychiatric hospital.

A brief summary of the civil commitment process:

The civil commitment process (also called involuntary commitment) begins when someone – usually a family member, but under state law it can be anyone – files paperwork with the county chancery clerk’s office alleging that another person is so sick that they are a danger to themselves or others. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are common diagnoses, but not everyone who gets committed has a serious mental illness.

Then the person can be taken into custody by county sheriff’s deputies. They may wait at a medical facility for evaluations, a hearing and treatment– or if no publicly funded bed is available, they can sit in a jail cell with no criminal charges, receiving minimal care in the midst of a mental health crisis, until a treatment bed opens up.

The Department of Mental Health says the process from initial evaluation to court hearing should take seven to 10 days, but it can take longer. If the judge orders someone hospitalized, they typically join the waiting list for a state hospital or crisis bed.

Last fiscal year, the average wait time in jail for a state hospital bed after a hearing fell to just under five days from more than eight days the year before as the Department of Mental Health reopened state hospital beds. It’s not clear how much time Mississippians spend jailed without criminal charges before their commitment hearings. Legislation passed last year requires counties to report to the DMH about where people are held both before and after their hearings, so more information should be available soon.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Two Mississippi media companies appeal Supreme Court ruling on sealed court files

A three-judge panel of the Mississippi Supreme Court has ruled that court records in a politically charged business dispute will remain confidential, even though courts are supposed to be open to the public.

The panel, comprised of Justice Josiah Coleman, Justice James Maxwell and Justice Robert Chamberlin, denied a request from Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald that sought to force Chancery Judge Neil Harris to unseal court records in a Jackson County Chancery Court case or conduct a hearing on unsealing the court records.

The Supreme Court panel did not address whether Harris erred by sealing court records and it has not forced the judge to comply with the court’s prior landmark decisions detailing how judges are allowed to seal court records in extraordinary circumstances.

The case in question has drawn a great deal of public interest. The lawsuit seeks to dissolve a company called Securix Mississippi LLC that used traffic cameras to ticket uninsured motorists in numerous cities in the state.

The uninsured motorist venture has since been disbanded and is the subject of two federal lawsuits, neither of which are under seal. In one federal case, an attorney said the chancery court file was sealed to protect the political reputations of the people involved.

READ MORE: Private business ticketed uninsured Mississippi vehicle owners. Then the program blew up.

Quinton Dickerson and Josh Gregory, two of the leaders of QJR, are the owners of Frontier Strategies. Frontier is a consulting firm that has advised numerous elected officials, including four sitting Supreme Court justices. The three justices who considered the media’s motion for relief were not clients of Frontier.

The two news outlets on Thursday filed a motion asking the Supreme Court for a rehearing.

Courts are open to public

In their motion for a rehearing, the media companies are asking that the Supreme Court send the case back to chancery court, where Harris should be required to give notice and hold a hearing to discuss unsealing the remaining court files.

Courts and court files are supposed to be open and accessible to the public. The Supreme Court has, since 1990, followed a ruling that lays out a procedure judges are supposed to follow before closing any part of a court file. The judge is supposed to give 24 hours notice, then hold a hearing that gives the public, including the media, an opportunity to object.

At the hearing, the judge must consider alternatives to closure and state any reasons for sealing records.

Instead, Harris closed the court record without explanation the same day the case was filed in September 2024. In June, Harris denied a motion from Mississippi Today to unseal the file.

The case, he wrote in his order, is between two private companies. “There are no public entities included as parties,” he wrote, “and there are no public funds at issue. Other than curiosity regarding issues between private parties, there is no public interest involved.”

But that is at least partially incorrect. The case involves Securix Mississippi working with city police departments to ticket uninsured motorists. The Mississippi Department of Public Safety had signed off on the program and was supposed to be receiving a share of the revenue.

Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald then filed for relief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Harris improperly closed the court file without notice and did not conduct a hearing to consider alternatives.

After the media outlets’ appeal to the Supreme Court, Harris ordered some of the records in the case to be unsealed.

But he left an unknown number of exhibits under seal, saying they contain “financial information” and are being held in a folder in the Chancery Clerk’s Office.

File improperly sealed, media argues

The three-judge Supreme Court panel determined the media appeal was no longer relevant because Harris had partially unsealed the court file.

In the news outlets’ appeal for rehearing, they argue that if the Supreme Court does not grant the motion, the state’s highest court would virtually give the press and public no recourse to push back on judges when they question whether court records were improperly sealed.

“The original … sealing of the entire file violated several rights of the public and press … which if not overruled will be capable of repetition yet, evading review,” the motion reads.

The media companies also argue that Harris’ order partially unsealing the chancery court case was not part of the record on appeal and should not have been considered by the Supreme Court. His order to partially unseal the case came 10 days after Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald filed their appeal to the Supreme Court.

READ MORE: Judge holds secret hearing in business fight over uninsured motorist enforcement

Charlie Mitchell, a lawyer and former newspaper editor who has taught media law at the University of Mississippi for years, called Judge Harris’ initial order keeping the case sealed “illogical.” He said the judge’s second order partially unsealing the case appears “much closer” to meeting the court’s standard for keeping records sealed, but the judge could still be more specific and transparent in his orders.

Instead of simply labeling the sealed records as “financial information,” Mitchell said the Supreme Court could promote transparency in the judiciary by ordering Harris to conduct a hearing — something he should have done from the outset — or redact portions of the exhibits.

“Closing a record or court matter as the preference of the parties is never — repeat never — appropriate,” Mitchell said. “It sounds harsh, but if parties don’t want the public to know about their disputes, they should resolve their differences, as most do, without filing anything in a state or federal court.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Two Mississippi media companies appeal Supreme Court ruling on sealed court files appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content focuses on transparency, accountability, and the public’s right to access court records, which aligns with values often emphasized by center-left perspectives. It critiques the sealing of court documents and advocates for media and public oversight of judicial processes, reflecting a concern for government openness and checks on power. However, the article maintains a factual tone without overt political partisanship, situating it slightly left of center due to its emphasis on transparency and media rights.

Mississippi Today

Judge: Felony disenfranchisement a factor in ruling on Mississippi Supreme Court districts

The large number of Mississippians with voting rights stripped for life because they committed a disenfranchising felony was a significant factor in a federal judge determining that current state Supreme Court districts dilute Black voting strength.

U.S. District Judge Sharion Aycock, who was appointed to the federal bench by George W. Bush, last week ruled that Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts violate the federal Voting Rights Act and that the state cannot use the same maps in future elections.

Mississippi law establishes three Supreme Court districts, commonly referred to as the northern, central and southern districts. Voters elect three judges from each to the nine-member court. These districts have not been redrawn since 1987.

READ MORE: Mississippians ask U.S. Supreme court to strike state’s Jim Crow-era felony voting ban

The main district at issue in the case is the central district, which comprises many parts of the majority-Black Delta and the majority-Black Jackson Metro Area.

Several civil rights legal organizations filed a lawsuit on behalf of Black citizens, candidates, and elected officials, arguing that the central district does not provide Black voters with a realistic chance to elect a candidate of their choice.

The state defended the districts arguing the map allows a fair chance for Black candidates. Aycock sided with the plaintiffs and is allowing the Legislature to redraw the districts.

The attorney general’s office could appeal the ruling to the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. A spokesperson for the office stated that the office is reviewing Aycock’s decision, but did not confirm whether the office plans to appeal.

In her ruling, Aycock cited the testimony of William Cooper, the plaintiff’s demographic and redistricting expert, who estimated that 56,000 felons were unable to vote statewide based on a review of court records from 1994 to 2017. He estimated 60% of those were determined to be Black Mississippians.

Cooper testified that the high number of people who were disenfranchised contributed to the Black voting age population falling below 50% in the central district.

Attorneys from Attorney General Lynn Fitch’s office defended the state. They disputed Cooper’s calculations, but Aycock rejected their arguments.

The AG’s office also said Aycock should not put much weight on the number of disenfranchised people because the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals previously ruled that Mississippi’s disenfranchisement system doesn’t violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Aycock, however, distinguished between the appellate court’s ruling that the system did not have racial discriminatory intent and the current issue of the practice having a racially discriminatory impact.

“Notably, though, that decision addressed only whether there was discriminatory intent as required to prove an Equal Protection claim,” Aycock wrote. “The Fifth Circuit did not conclude that Mississippi’s felon disenfranchisement laws have no racially disparate impact.”

Mississippi has one of the harshest disenfranchisement systems in the nation and a convoluted method for restoring voting rights to people.

Other than receiving a pardon from the governor, the only way for someone to regain their voting rights is if two-thirds of legislators from both chambers at the Capitol, the highest threshold in the Legislature, agree to restore their suffrage.

Lawmakers only consider about a dozen or so suffrage restoration bills during the session, and they’re typically among the last items lawmakers take up before they adjourn for the year.

Under the Mississippi Constitution, people convicted of a list of 10 types of felonies lose their voting rights for life. Opinions from the Mississippi Attorney General’s Office have since expanded the list of specific disenfranchising felonies to 23.

The practice of stripping voting rights away from people for life is a holdover from the Jim Crow era. The framers of the 1890 Mississippi Constitution believed Black people were most likely to commit certain crimes.

Leaders in the state House have attempted to overhaul the system, but none have gained any significant traction in both chambers at the Capitol.

Last year, House Constitution Chairman Price Wallace, a Republican from Mendenhall, advocated a constitutional amendment that would have removed nonviolent offenses from the list of disenfranchising felonies, but he never brought it up for a vote in the House.

Wallace and House Elections Chairman Noah Sanford, a Republican from Collins, are leading a study committee on Sept. 11 to explore reforms to the felony suffrage system and other voting legislation.

Wallace previously said on an episode of Mississippi Today’s “The Other Side” podcast that he believes the state should tackle the issue because one of his core values, part of his upbringing, is giving people a second chance, especially once they’ve made up for a mistake.

“This issue is not a Republican or Democratic issue,” Wallace said. “It allows a woman or a man, whatever the case may be, the opportunity to have their voice heard in their local elections. Like I said, they’re out there working. They’re paying taxes just like you and me. And yet they can’t have a decision in who represents them in their local government.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Judge: Felony disenfranchisement a factor in ruling on Mississippi Supreme Court districts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a focus on voting rights and racial justice issues, highlighting the impact of felony disenfranchisement on Black voters in Mississippi. It emphasizes civil rights concerns and critiques longstanding policies rooted in the Jim Crow era, which aligns with center-left perspectives advocating for expanded voting access and systemic reform. The coverage is factual and includes viewpoints from multiple sides, but the framing and emphasis on racial disparities and voting rights restoration suggest a center-left leaning.

Mississippi Today

Jackson police chief steps down to take another job, national search to come

Jackson Police Department Chief Joseph Wade told the mayor last week he was choosing to retire after 29 years of service and two years at the helm of the force. Wade said he’d been given another job opportunity, which has yet to be announced.

His last day is Sept. 5.

Mayor John Horhn said he told Wade the officer would be crazy not to take the job — one that comes with less stress and more pay.

“His wife has been on his back, his blood pressure has been up,” Horhn said during Tuesday’s City Council meeting. “He has done a commendable job.”

Wade became chief during a period in which Jackson was called the murder capital of America. Under his tenure, Wade said crime has fallen markedly, including a roughly 45% reduction in homicides so far this year compared to the same period in 2024, the Clarion Ledger reported. He said he’s also increased JPD’s force by 37, for a total of 258 officers.

Wade said his biggest accomplishment is reestablishing trust. “We are no longer the laughing stock of the law enforcement community,” he said.

The chief’s departure comes less than two months after Horhn took office, replacing former Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba who originally appointed Wade, and on the heels of a spate of shootings that Wade said were driven by gangs of young men.

“I have received so many calls from the community: ‘Chief, please don’t leave us,'” Wade told the crowd in council chambers.

But Wade said he “would rather leave prematurely than overstay my welcome,” adding that the average tenure of a police chief is 2.5 years.

Wade said that last year he stood next to Jackson Councilman Kenny Stokes and told the media he was going to cut crime in half, “And what did I do? Cut it in half,” he said.

“What I’ve seen in our community in some situations is people want police, but they don’t want to be policed,” Wade said.

Hinds County Sheriff Tyree Jones will serve as interim police chief until the administration finds a replacement. Jones said he has not finalized a contract with the city, responding to a question about whether he will draw a salary from both agencies.

“I could think of no one better than the sheriff of Hinds County,” Horhn said, adding that the appointment is temporary.

Jones said during the meeting that his responsibility as sheriff will continue uninterrupted and that his goal within JPD is to ensure continued professionalism in the department.

“I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my dear friend and retired police chief Joe Wade,” Jones said. “Again, let me be clear, I have no aspirations to permanently hold the position.”

Horhn said there is precedence for the dual role that “Chief Sheriff Jones is about to embark upon,” citing former mayor Frank Melton’s hiring of Sheriff Malcolm McMillin.

The city has enlisted help from former U.S. Marshal George White and the former chief of the Mississippi Highway Patrol, Col. Charles Haynes, to lead the Law Enforcement Task Force that will conduct a nationwide search to fill the position. The administration expects that to take between 30 and 60 days, according to a city press release.

The release said the task force will also examine safety challenges in Jackson more broadly, such as youth crime, drug crimes, departmental needs and interagency coordination.

“I am grateful that Marshal White and Col. Haynes have agreed to lead this important effort. Their breadth of experience, commitment to public safety and deep understanding of law enforcement challenges will ensure the task force conducts a rigorous search for our next chief,” said Horhn. “I am confident they will help shape solutions that address the evolving needs of Jackson.”

The city said it would soon release details about the opportunity for the public to offer input on the process.

“Hinds County is all in for whatever we have to do to make Jackson and Hinds County the safest it can be,” Hinds County Supervisors President Robert Graham said during the meeting.

Wade, who hails from nearby Terry, graduated from JPD’s 23rd recruit class in 1995, rising from a police recruit and hitting every rung of the ladder on his way to chief. “I was homegrown,” he said.

Wade said he received “an amazing offer in a private sector at an amazing organization. Don’t ask me where. That will be released at the appropriate time.”

This story may be updated.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Jackson police chief steps down to take another job, national search to come appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a straightforward news report on the resignation of a police chief, focusing on facts, quotes from officials, and crime statistics without evident ideological framing. It covers perspectives from multiple local government figures and avoids partisan language, reflecting a neutral, balanced tone typical of centrist reporting.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

DEA agents uncover 'torture chamber,' buried drugs and bones at Kentucky home

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed3 days ago

Racism Wrapped in Rural Warmth

-

The Center Square7 days ago

Georgia ICE arrests up 367 percent from 2021, making for ‘safer streets, open jobs | Georgia

-

Local News7 days ago

Florida must stop expanding ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ immigration center, judge says

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

The Dixon: Writing a New Story for Main Street in Natchez

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

Tom Cole’s Powerful Spot on the Appropriations Committee Is Motivating Him to Stay in Congress

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Quintissa Peake, ‘sickle cell warrior’ and champion for blood donation, dies at 44

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Abrego Garcia released from prison, headed to family