A high drug failure rate is more than just a pattern recognition problem.

Duxin Sun, University of Michigan and Christian Macedonia, University of Michigan

The potential of using artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development has sparked both excitement and skepticism among scientists, investors and the general public.

“Artificial intelligence is taking over drug development,” claim some companies and researchers. Over the past few years, interest in using AI to design drugs and optimize clinical trials has driven a surge in research and investment. AI-driven platforms like AlphaFold, which won the 2024 Nobel Prize for its ability to predict the structure of proteins and design new ones, showcase AI’s potential to accelerate drug development.

AI in drug discovery is “nonsense,” warn some industry veterans. They urge that “AI’s potential to accelerate drug discovery needs a reality check,” as AI-generated drugs have yet to demonstrate an ability to address the 90% failure rate of new drugs in clinical trials. Unlike the success of AI in image analysis, its effect on drug development remains unclear.

Behind every drug in your pharmacy are many, many more that failed.

We have been following the use of AI in drug development in our work as a pharmaceutical scientist in both academia and the pharmaceutical industry and as a former program manager in the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA. We argue that AI in drug development is not yet a game-changer, nor is it complete nonsense. AI is not a black box that can turn any idea into gold. Rather, we see it as a tool that, when used wisely and competently, could help address the root causes of drug failure and streamline the process.

Most work using AI in drug development intends to reduce the time and money it takes to bring one drug to market – currently 10 to 15 years and US$1 billion to $2 billion. But can AI truly revolutionize drug development and improve success rates?

AI in drug development

Researchers have applied AI and machine learning to every stage of the drug development process. This includes identifying targets in the body, screening potential candidates, designing drug molecules, predicting toxicity and selecting patients who might respond best to the drugs in clinical trials, among others.

Between 2010 and 2022, 20 AI-focused startups discovered 158 drug candidates, 15 of which advanced to clinical trials. Some of these drug candidates were able to complete preclinical testing in the lab and enter human trials in just 30 months, compared with the typical 3 to 6 years. This accomplishment demonstrates AI’s potential to accelerate drug development.

On the other hand, while AI platforms may rapidly identify compounds that work on cells in a Petri dish or in animal models, the success of these candidates in clinical trials – where the majority of drug failures occur – remains highly uncertain.

Unlike other fields that have large, high-quality datasets available to train AI models, such as image analysis and language processing, the AI in drug development is constrained by small, low-quality datasets. It is difficult to generate drug-related datasets on cells, animals or humans for millions to billions of compounds. While AlphaFold is a breakthrough in predicting protein structures, how precise it can be for drug design remains uncertain. Minor changes to a drug’s structure can greatly affect its activity in the body and thus how effective it is in treating disease.

Survivorship bias

Like AI, past innovations in drug development like computer-aided drug design, the Human Genome Project and high-throughput screening have improved individual steps of the process in the past 40 years, yet drug failure rates haven’t improved.

Most AI researchers can tackle specific tasks in the drug development process when provided with high-quality data and particular questions to answer. But they are often unfamiliar with the full scope of drug development, reducing challenges into pattern recognition problems and refinement of individual steps of the process. Meanwhile, many scientists with expertise in drug development lack training in AI and machine learning. These communication barriers can hinder scientists from moving beyond the mechanics of current development processes and identifying the root causes of drug failures.

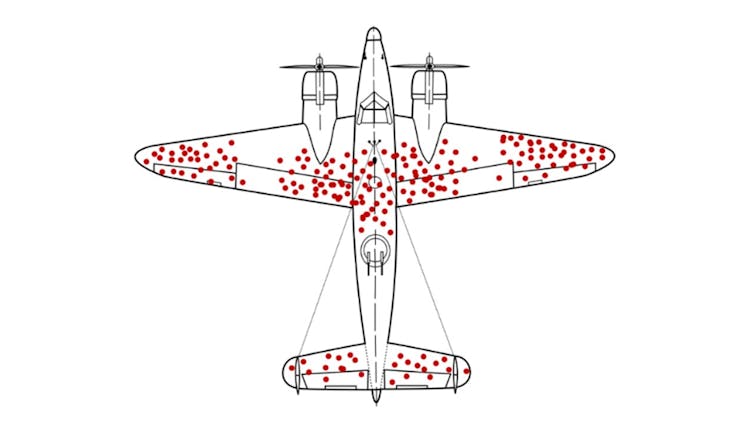

Current approaches to drug development, including those using AI, may have fallen into a survivorship bias trap, overly focusing on less critical aspects of the process while overlooking major problems that contribute most to failure. This is analogous to repairing damage to the wings of aircraft returning from the battle fields in World War II while neglecting the fatal vulnerabilities in engines or cockpits of the planes that never made it back. Researchers often overly focus on how to improve a drug’s individual properties rather than the root causes of failure.

While returning planes might survive hits to the wings, those with damage to the engines or cockpits are less likely to make it back. Martin Grandjean, McGeddon, US Air Force/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The current drug development process operates like an assembly line, relying on a checkbox approach with extensive testing at each step of the process. While AI may be able to reduce the time and cost of the lab-based preclinical stages of this assembly line, it is unlikely to boost success rates in the more costly clinical stages that involve testing in people. The persistent 90% failure rate of drugs in clinical trials, despite 40 years of process improvements, underscores this limitation.

Addressing root causes

Drug failures in clinical trials are not solely due to how these studies are designed; selecting the wrong drug candidates to test in clinical trials is also a major factor. New AI-guided strategies could help address both of these challenges.

Currently, three interdependent factors drive most drug failures: dosage, safety and efficacy. Some drugs fail because they’re too toxic, or unsafe. Other drugs fail because they’re deemed ineffective, often because the dose can’t be increased any further without causing harm.

We and our colleagues propose a machine learning system to help select drug candidates by predicting dosage, safety and efficacy based on five previously overlooked features of drugs. Specifically, researchers could use AI models to determine how specifically and potently the drug binds to known and unknown targets, the level of these targets in the body, how concentrated the drug becomes in healthy and diseased tissues, and the drug’s structural properties.

These features of AI-generated drugs could be tested in what we call phase 0+ trials, using ultra-low doses in patients with severe and mild disease. This could help researchers identify optimal drugs while reducing the costs of the current “test-and-see” approach to clinical trials.

While AI alone might not revolutionize drug development, it can help address the root causes of why drugs fail and streamline the lengthy process to approval.

Duxin Sun, Associate Dean for Research, Charles Walgreen Jr. Professor of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Michigan and Christian Macedonia, Adjunct Professor in Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.