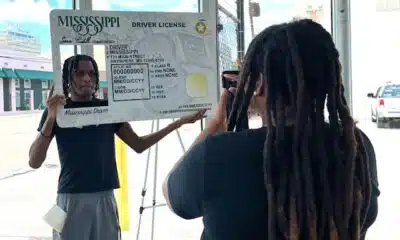

Carlos Moreno/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Undocumented immigration is a key issue in American politics, but it can be hard to nail down the basic facts about who these immigrants are, where they live and how their numbers have changed in the past few decades.

I study the demographics of the U.S. immigrant population and have seen how the data has changed over time. Here are some basics to set the stage as President Donald Trump begins his second term in office vowing to crack down hard on immigrants, including by conducting mass deportations.

Immigration status

My analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey data, in collaboration with the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit immigration research group, finds that as of the middle of 2023, approximately 51 million foreign-born people lived in the United States.

Most immigrants are in the U.S. legally. About 49% have become U.S. citizens by a process known as naturalization. Another 19% hold lawful permanent resident status and are eligible to become U.S. citizens through naturalization. Still another 5% are in the country on temporary visas, like those for international students, diplomats and their families, and seasonal or temporary workers.

The remaining 27% – around 13.7 million people – are outside those categories and therefore generally considered to be undocumented.

My analysis shows that the number of undocumented immigrants held steady at around 11 million between 2007 and 2019. In the next four years, the numbers increased by nearly 3 million. This recent growth is mostly attributable to large increases in border crossings by migrants from Central and South America who were seeking asylum or other forms of humanitarian relief. Starting in June 2024, however, the number of people entering across the U.S.-Mexico border fell back to normal levels when the Biden administration implemented the Secure the Border rule, which suspends asylum applications at the border when crossings reach a seven-day average of 2,500.

These changes were accompanied by changes in the undocumented migration process itself. In the past, undocumented immigrants often entered the country by slipping undetected across the U.S. border with Mexico. But increased border enforcement made the journey more dangerous and expensive.

Instead of paying smugglers or risking their lives in the desert, growing numbers of undocumented immigrants now either directly approach immigration officials at airports or land-border crossings and seek asylum in the U.S. Others are initially admitted to the country legally on a temporary tourist, student or work visa – but then overstay the time period for which they have permission.

Additionally, growing numbers of undocumented immigrants occupy what might be called a “liminal” or “in-between” status. The Migration Policy Institute analysis estimates this encompasses a range of groups as of the middle of 2023, including:

- About 2.1 million people awaiting a decision on their asylum claims.

- 521,000 parolees, allowed into the U.S. for humanitarian or national security reasons, like those paroled recently from Afghanistan and Ukraine.

- 654,000 people who hold temporary protected status because it would be unsafe for them to return home due to armed conflict, natural disasters and other emergencies.

- 562,000 who are protected by the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program because they were brought to the United States as children by their parents.

The report estimates that just over one-quarter of undocumented immigrants currently occupy this type of “in-between” status. These immigrants are protected from deportation. Some even have a legal right to work in the U.S. Yet they do not possess a durable legal immigration status, and their rights could be threatened by policy changes.

While Trump says he wants to deport as many as 11 million immigrants, analyses published by The New York Times and The Washington Post indicate that it may be difficult to remove many of them under existing U.S. law. The one group that is easy to remove – those with a criminal record – is relatively small, numbering about 650,000.

Shifting countries of origin

Since 1980, Mexicans have been the largest single national origin group in the United States. I found that 10.9 million Mexican-born individuals were living in the country in 2023, making up 23% of all immigrants. The second-largest group, immigrants from India, numbered just 2.9 million, or 6% of all immigrants living in the U.S.

However, immigrants’ origins have been shifting away from Mexico.

With the onset of the Great Recession of 2007-2009, work opportunities in U.S. construction and manufacturing evaporated. Many Mexican laborers had been working in construction at the time but went back to Mexico when the U.S. housing market collapsed.

At that same time, Mexico’s economic conditions improved, its population growth slowed, and many would-be migrants opted to stay home. For the first time in decades, from 2007 to 2022 the number of Mexicans who returned home exceeded the number coming to the United States.

This trend was especially pronounced among undocumented immigrants. I found that Mexicans made up about 51% of the undocumented immigrants who arrived in the country 10 or more years ago. Central Americans made up 20%, and the remaining originated from other regions.

However, undocumented migrants now come from across the globe. Among undocumented immigrants who arrived within the past 10 years, 19% came from Mexico. Larger shares came from Central America and South America. While some of these new migrants seek work, others flee crime, economic and ecological disasters, and political persecution in their home countries.

Duration of residence

Most immigrants, whether they are in the U.S. legally or illegally, have lived in the United States for many years. Just under half of foreign-born individuals have lived in the country for two decades or more, and more than two-thirds have lived in the country for at least 10 years. Only 20% arrived within the past five years.

This is a dramatic change from the early 2000s, when less than 10% of immigrants had been in the U.S. for more than two decades, and more than one-third had arrived within the previous five years.

That means many of the people who are likely to be targeted for deportation in the coming months are settled, long-term members of American society.

Place of residence

As of 2023, 6.6 million immigrants reported on the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey that they moved to the United States in the past five years.

However, the effects of these new immigrants on American communities has been uneven. Although most communities are more racially and ethnically diverse now than in the past, the numbers of newly arrived immigrants are relatively low in most places.

Fifteen states host fewer than 20,000 immigrants, and 33 states are home to fewer than 100,000. In contrast, over half of new arrivals live in just five states: California, Florida, Illinois, New York and Texas are the home of over half of new arrivals yet have only 37% of the U.S. population. Other states such as Georgia, Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Washington also are home to large and growing immigrant populations.

The U.S. immigrant population is changing rapidly. In the early years of the 21st century, Mexican immigrants dominated undocumented immigration flows to the United States. Decades later, many of these people continue to live in the country.

In the past four years, however, the flow of undocumented people increased dramatically. These new arrivals tend to come from troubled nations in Central and South America, many of whom are protected from deportation and have a legal right to work in the U.S. Altogether, most undocumented immigrants either have lived in the country for decades or have legal protections.

Neither of these groups fit the profile of undocumented immigrants who are typically targeted for deportation.

Jennifer Van Hook, Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Demography, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.