Pius Utomi Ekpei/AFP via Getty Images

Amy E. Stambach, University of Wisconsin-Madison

The U.S. government is relaxing federal vaccine requirements and cutting vaccine research and development funding here at home. Elsewhere, it’s going even further.

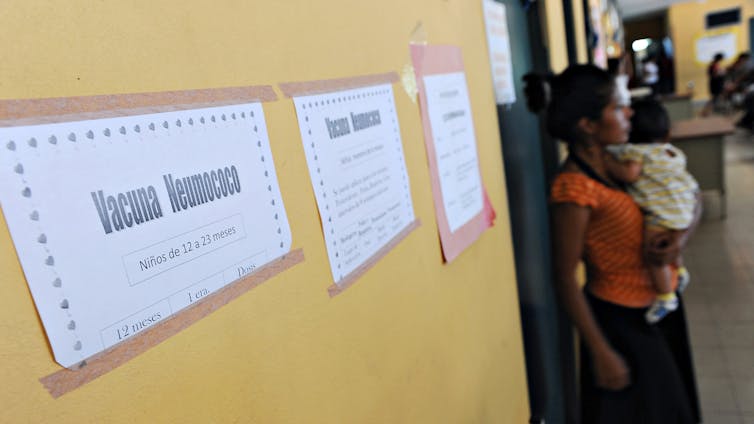

The Trump administration has stopped funding Gavi, a global initiative that helps millions of children in low-income and medium-income countries get vaccinated against measles, cholera and other preventable diseases. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, is an international organization that collects money from government and private donors. It spends around US$1.7 billion annually to buy and deliver vaccines.

Gavi has helped vaccinate over 1.1 billion children in 78 countries since 2000. Those vaccinations, according to the alliance, have prevented more than 18 million deaths from meningitis, diphtheria, tetanus, polio and other deadly diseases – saving more than $250 billion in health and economic costs.

In 2024, the U.S. was its third-biggest funder – after the U.K. and the Gates Foundation. It contributed $3.7 billion between 2000 and early 2025.

The Biden administration had promised to kick in $1.6 billion over five years beginning in 2026, plus another $300 million for the rest of 2025.

But Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced on June 26, 2025, that the Trump administration would not honor those commitments, ripping a gaping hole in Gavi’s budget.

Elmer Martinez/AFP via Getty Images

Becoming more reliant on philanthropy

Kennedy criticized what he alleged was Gavi’s weak track record on vaccine safety.

Many scientists and pediatricians have disputed his rationale for cutting funding, partly because Kennedy referred to a single, contested study in his remarks that was based on 40-year-old data.

So far, Gavi’s other donors – a mix of nations, foundations, drugmakers and other corporations, including Cisco, Mastercard and Shell – haven’t said they’ll step up their support enough to plug the $3 billion hole in Gavi’s five-year plan. But several of the initiative’s biggest donors, particularly the U.K. and the Gates Foundation, have reiterated their commitments of $1.7 and $1.6 billion, respectively, to be disbursed from 2026 to 2030.

In the meantime, Gavi is trying to cut costs and is seeking new funders. Unless other governments decide to make up for the loss of U.S. funding, which so far they have not, Gavi will likely become more dependent on philanthropy than ever before.

In 2024, more than 20% of its funding came from companies and foundations. Now, the vaccine alliance wants to grow that percentage, in part by slowly gaining new donors.

In my research with collaborators on vaccine hesitancy, and through fieldwork in clinics in South Africa and Tanzania, I have seen both the strengths and weaknesses of Gavi’s reliance on the Gates Foundation and corporate donors. These donors either provide funding for vaccines or donate vaccines directly for Gavi to distribute.

While most of the media coverage of the U.S. halting its funding focuses on the fact that U.S. pullout is likely to mean that more children around the world will die, I’m also concerned about another issue.

Pavlo Gonchar/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Encountering some complications

When philanthropy helps fill funding gaps in the public sphere, challenges can arise.

Gavi’s vaccine programs have undoubtedly increased childhood vaccination rates. But they would be even more helpful if they could more consistently help countries build the strong and lasting vaccination systems that low-income and medium-income countries need to make sure vaccines can eventually be delivered without foreign aid.

One problem is that corporate donors and foundations don’t have to answer to voters or taxpayers in the countries they give money to. This can make it harder for countries where Gavi operates to understand philanthropic decisions.

Gavi has received more funding from the Gates Foundation than from any other private contributor. The foundation says it has disbursed or pledged, since Gavi’s launch in 2000, a total of $30.6 billion to “advance vaccines – investing in their discovery, development, and distribution.” And $7.7 billion of that sum has been “directed to Gavi” to vaccinate kids.

In so doing, the Gates Foundation, which announced on Aug. 4, 2024, that it intended to devote $2.5 billion toward improving women’s health care around the world by 2030, has helped Gavi vaccinate more children against preventable diseases than government money alone could have accomplished.

But when one donor wields that much influence, I’ve observed, tensions can follow.

I heard about such tensions at African vaccine clinics where I conducted research between 2021 and 2023.

Thierry Monasse/Getty Images

Concerns about influence

At clinics across South Africa, Tanzania and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, I spoke with doctors, nurses and public health officials working directly with Gavi-supported programs. Many of the people I interviewed acknowledged the vital role the Gates Foundation has played in expanding access to vaccines.

I am not naming the people who I interviewed to protect their confidentiality, in keeping with social science research norms.

But many expressed concern about the outsized influence that can follow when one donor gives so much money. For example, several people I interviewed said they believed they had no control over which brand of vaccines to use or which age group to vaccinate first.

“That’s all decided by donor offices – not by our own (health) ministry,” said a doctor in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. She pointed to the walls of her clinic, plastered with promotional posters for the Gates Foundation and Gavi.

Gavi, however, says on its website that its board chooses the vaccines it invests in after extensive research.

And many of the people I interviewed said they believed that some donors push for vaccines made by companies they have invested in through their endowments and other assets.

Health workers also told me that Gates Foundation-funded reporting requirements added pressure and extra work without improving care. A district health official in rural Tanzania said his clinic had to meet strict targets set by a Gates Foundation–backed program. This meant quickly submitting forms with detailed information about numbers vaccinated and each patient’s health history – sometimes taking a toll on the quality of care.

“We’re spending more time filling out reports for the donor than talking to patients,” he said. Because the clinic had no computers and lacked a stable flow of electricity, keeping up with the paperwork was tedious.

Across interviews and locations, a common pattern emerged. I frequently heard that the Gates Foundation had helped clinics operate and pay staff with its grant money, but its programs followed a business model focused on meeting targets and showing results.

“It’s all about hitting numbers, not building systems,” one official in Cape Town, South Africa, told me. Many health care workers said this model shifted public health priorities toward the Gates Foundation’s goals at the expense of developing sustainability.

AP Photo/ Christopher Furlong

The limits of philanthropy

Funding from foreign governments can also shift local priorities, though possibly to a lesser degree than philanthropy. That’s because governments often work through bilateral agreements and are subject to diplomatic protocols and political accountability, which can temper their influence. In contrast, large foundations like the Gates Foundation may operate with more autonomy – allowing them to shape programs more directly around their goals.

Ultimately, without democratic oversight or deep roots where they donate, foreign philanthropy can be seen as overriding local priorities. Donations from foundations and corporations can be perceived as exerting influence over public health goals, stirring resentment.

The Gates Foundation agrees that philanthropy cannot replace U.S. government assistance.

“There is no foundation – or group of foundations – that can provide the funding, workforce capacity, expertise, or leadership that the United States has historically provided to combat deadly diseases and address hunger and poverty,” Rob Nabors, director of the North America Program at the Gates Foundation, wrote in response to a query from me.

Nabors’ statement underscores why the end of U.S. government funding for, and involvement in, Gavi matters.

The U.S. government has historically engaged in diplomacy and forged long-term partnerships with health ministries in other countries. It has also traditionally spent billions of dollars on infrastructure, like research labs and refrigerated systems to store and transport vaccines.

Foundations typically don’t operate on the scale of government aid operations.

The Gates Foundation provided some information upon request that pointed to efforts it has made in this regard. For example, it had spent $1 billion by 2018 to support vaccine manufacturers located in developing countries and “related grantees,” working with 19 of those manufacturers in “11 countries to bring 17 vaccines to market.” It also pointed to the $15 million it announced in 2022 for a “South African specialty pharmaceutical company to support its capabilities to manufacture lifesaving routine and outbreak vaccines for Africa.”

Regardless of where its funding comes from, Gavi is essential for everyone, including Americans, because diseases like measles don’t respect borders. Because global air travel shuffles millions of people around the world daily, an outbreak of a very contagious disease anywhere can become a threat everywhere. That makes U.S. funding for Gavi not just an act of generosity toward people in other countries, but one of protecting the U.S. as well.

The Gates Foundation has provided funding for The Conversation U.S. and provides funding for The Conversation internationally.

Amy E. Stambach, Professor of Cultural Anthropology and International Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.