Mississippi Today

This DeSoto Co. hospital transfers some patients to jail to await mental health treatment

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today and co-published with the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, the Sun Herald and MLK50. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

When Sandy Jones’ 26-year-old daughter started writing on the walls of her home in Hernando, Mississippi, last year and talking angrily to the television, Sandy said, she knew two things: Her daughter Sydney needed help, and Sandy didn’t want her to be held in jail again to get it.

A year and a half earlier, during Sydney Jones’ first psychotic episode, her mother filed paperwork to have her involuntarily committed, a legal process in which a judge can order someone to receive mental health treatment. After DeSoto County sheriff’s deputies showed up at Sydney’s home and explained that they were detaining her for a mental evaluation, Sydney panicked and ran inside. Following a struggle, deputies cuffed and shackled her and drove her to the county jail, where people going through the commitment process are usually held as they await mental health treatment elsewhere.

Over nine days in jail, Sydney Jones said, she believed her tattoos were portals for spiritual forces and felt like she had been abandoned by her family. In an interview, she said that the experience was so traumatic that she became anxious when she drove, afraid she could be arrested at any moment.

The second time Sydney Jones experienced delusions, in 2023, a family member contacted the local community mental health center for help. Police officers with mental health training came and called an ambulance to take Jones to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, part of a large, religiously affiliated nonprofit hospital system. But because the hospital doesn’t have a psychiatric unit, after a few days it sent her to the jail to wait for eventual treatment in a publicly funded facility. Like the first time, she hadn’t been charged with a crime.

Roughly 200 people in DeSoto County were jailed annually during the civil commitment process, most without criminal charges, between 2021 and 2023. About a fifth of them were picked up at local hospitals, according to an estimate based on a review of Sheriff’s Department records by Mississippi Today and ProPublica. The overwhelming majority of those patients, according to our analysis, were at Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, the largest in this prosperous, suburban county near Memphis.

“That would just be unthinkable here,” said Dr. Grayson Norquist, the chief of psychiatry at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, a professor at Emory University and the former chair of psychiatry at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi.

Norquist was one of 17 physicians specializing in emergency medicine or psychiatry, including leaders in their fields, who said they had never heard of a hospital sending patients to jail solely to wait for mental health treatment. Several said it violates doctors’ Hippocratic oath: to do no harm.

The practice appears to be unusual even in Mississippi, where lawmakers recently acted to limit when people can be jailed as they go through the civil commitment process. Sheriff’s departments in about a third of the state’s counties, including those that appear to jail such people most frequently, responded to questions from Mississippi Today and ProPublica about how they handle involuntary commitment. They said they seldom, if ever, take people who need mental health treatment from a hospital to jail. At most, said sheriffs in a few rural counties, they do it once or twice a month.

But in DeSoto County, hospital patients were jailed about 50 times a year from 2021 to 2023, according to the news outlets’ estimate, which was based on a review of Sheriff’s Department dispatch logs, incident reports and jail dockets.

At least two people have died soon after being taken from Baptist-DeSoto to a county jail during the commitment process, according to documents submitted for lawsuits filed over their deaths. One person died by suicide hours after arriving at the DeSoto County jail in 2021; the other died of multisystem organ failure after being jailed for three days in neighboring Marshall County in 2011. James Franks, an attorney who handles commitments for DeSoto County, said officials had no reason to believe that the woman who killed herself was suicidal. DeSoto County made a similar argument in a court filing in an ongoing lawsuit over that death, which didn’t name the hospital as a defendant. In lawsuits over the other death, a judge dismissed Marshall County and the sheriff as defendants, and a jury found that Baptist-DeSoto wasn’t liable.

Baptist-DeSoto officials said the hospital hands some patients over to deputies to take them to jail because those patients need dedicated treatment that the hospital can’t provide and nearby inpatient facilities are full. Most people who need inpatient treatment agree to be transferred to a behavioral health facility, according to Kim Alexander, director of public relations for Baptist Memorial Health Care Corp. But in a relatively small number of cases, she wrote in an email, patients are deemed dangerous to themselves or others and don’t agree to treatment, so they need to be committed. When that happens, she said, it’s the county’s responsibility to decide where to house them.

“We discharge mental health patients with the hope they will be transferred to a mental health facility that can provide the specialized care they need,” Alexander wrote in a statement. Jailing people who need mental health care is “not the ideal option,” she wrote. “Our hearts go out to anyone who cannot access the mental health care they need because behavioral health services are not available in the area.”

But doctors elsewhere said even if psychiatric facilities are full, Baptist-DeSoto doesn’t have to send patients to jail. They said the hospital could do what hospitals elsewhere in the country do: keep patients until a treatment bed is available.

“This is a principle of emergency medicine: You care for all people, under all circumstances, at any time,” said Dr. Lewis Goldfrank, who spent 50 years working in emergency medicine, including at Bellevue Hospital in New York City. Sending patients to jail because of their illness, he said, “is just unethical and irresponsible.”

Sandy Jones said she was in disbelief when it happened to her daughter. If Sydney has another psychotic episode, Sandy Jones said she won’t try to get help in DeSoto County. “I will tie her up until it’s over.”

Headed to Jail in a Hospital Gown and Handcuffs

Baptist, the largest and oldest hospital in DeSoto County, sits right off the interstate amid big-box stores and chain hotels in Southaven, Mississippi. It’s the first place many residents think of when they need medical help. Since 2017, it has served as the drop-off point for the county’s crisis intervention team, which was established to give law enforcement a way to help people with mental illness without bringing them to jail.

But when people show up in the emergency department needing inpatient psychiatric treatment, they don’t get it at Baptist-DeSoto. Instead, a crisis coordinator sets about finding some other place for them. If patients agree to treatment, they may be able to go to a publicly funded crisis unit, the closest of which is 50 miles away, or to a private psychiatric hospital. If they don’t, the crisis coordinator pursues commitment, which means turning patients over to the Sheriff’s Department. And because the Sheriff’s Department usually won’t transport patients over a long distance multiple times for a court hearing and eventual treatment, those patients usually go to jail.

That was the case with Sydney Jones. After she arrived at the hospital in April 2023, a psychiatrist contracted by the hospital evaluated her and concluded that she needed inpatient treatment. Jones was prescribed antipsychotic medication, admitted to the hospital, placed in her own room and monitored by a security guard.

Meanwhile, a staffer for Region IV, the local nonprofit community mental health center that works with Baptist-DeSoto to place patients who need treatment, was trying to find someplace for Jones other than the hospital. Catherine Davis, the crisis coordinator, concluded that Jones would need to be committed.

The next day, Davis contacted Jones’ cousin, who had tried to get Jones help, and asked the cousin to initiate commitment proceedings. (Region IV’s contract with Baptist-DeSoto requires it to try to get a patient’s family member or friend to file commitment paperwork before doing so itself.) The cousin refused because she knew Jones would be jailed until a bed opened up, according to Sandy Jones. (The cousin declined an interview request.)

So Davis filed the commitment paperwork herself, writing that Sydney Jones “should be taken to DeSoto County jail” while awaiting further evaluations, a court hearing and eventual treatment.

On Sydney Jones’ fourth day at Baptist-DeSoto, two sheriff’s deputies arrived. They received discharge papers from a nurse and wheeled Jones out of the hospital, according to her and an incident report. Jones, who said her delusions at the time were “like if Satan made goggles and put them on you,” was terrified that the deputies would drive her to a field, rape her and kill her.

Sandy Jones said she didn’t understand why she had no say in what was happening to her daughter, although that’s typical during the commitment process. “I felt like she was kidnapped from me,” Sandy Jones said. Her daughter spent nine days in jail before being admitted to a crisis unit, where she was treated for about two weeks.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica interviewed five other people who were discharged from Baptist to jail, including two who had been taken to the hospital because they had attempted suicide. One said that when deputies came to his room, he wondered if he had somehow committed a crime after trying to kill himself by overdosing on prescription medication. Another said he felt humiliated to be wheeled through the hospital wearing just a hospital gown. Three of the five said they were handcuffed before being taken away.

Hospital officials noted that all patients are medically stabilized before being released and that some patients are committed by family members. Dr. H. F. Mason, Baptist-DeSoto’s chief medical officer, said in an interview that he didn’t know how often patients who need behavioral health treatment might be discharged to jail, but he has no concerns about the practice. When hospital staff hand patients over to local authorities, Mason said, “we feel that they’re going to take the appropriate care of that patient.”

The jail, however, offers minimal psychiatric treatment, if any. Region IV staff members visit the jail primarily to evaluate people going through the commitment process or to check on people on suicide watch, Region IV Director Jason Ramey said. Jail officials said medical staff try to make sure inmates have access to their prescription drugs, although some people jailed during commitment proceedings have said they didn’t consistently get their medications.

Davis and county officials involved in the commitment process said sending patients to jail as they await treatment is better than allowing them to go home, which they see as the only other option. Jail is “not ideal, but we’ve got to make sure these people are safe so they’re not going to harm themselves or somebody else,” Davis said. “If they’ve had a serious suicide attempt, and they’re just adamant they’re going home, I mean — I can’t ethically let them go home. … We do try to explore all the options before we send them there.”

Once in jail, many patients wait days or weeks to be evaluated further, to go before a judge and to be taken somewhere for treatment, according to a review of jail dockets. One 37-year-old man picked up at Baptist-DeSoto in 2022 was jailed for nearly two months, which according to jail dockets was one of the longest detentions between 2021 and 2023.

The husband of a 64-year-old woman said that during the evaluation process he was encouraged by someone at Baptist-DeSoto — he doesn’t remember who — to pursue commitment proceedings after his wife stopped taking her bipolar disorder medication and overdosed on prescription drugs and alcohol. She was jailed for 28 days.

“I’m a Jehovah’s Witness,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified because she doesn’t want people to know she was jailed for mental illness. “I never known anything like that in my life. Never been arrested. All my rights just stripped from me. To do that to an old woman, because I was having mental troubles!”

She said the experience left her terrified to seek mental health care in DeSoto County. “I’d rather die than go back in there,” she said of the jail.

DeSoto County Struggles with a Problem Other Communities Have Addressed

Although DeSoto County has long relied on its jail to house people awaiting treatment, some communities elsewhere in the state have found other options. They rely on nearby crisis units to provide short-term treatment and in many cases have arrangements with local hospitals to treat patients if a publicly funded bed isn’t available.

On the Gulf Coast, people who come to hospitals in Ocean Springs or Pascagoula can be admitted to an eight-bed psychiatric unit, said Kim Henderson, director of emergency services for Singing River Health System, which operates those facilities.

Henderson said the psychiatric unit loses money because many patients lack insurance and can’t pay. “It would be so much easier to say we’re not going to do this anymore and shut it down,” she said. “But we don’t believe that’s the right thing to do.”

Over the years, DeSoto County officials have expressed frustration with how many people are jailed during the commitment process, but they’ve made little progress in coming up with an alternative.

In 2007, Baptist-DeSoto initiated 152 commitments, according to board meeting minutes and a news story in the DeSoto Times-Tribune; many of those patients went to jail. The hospital sends people “as quickly as they can to the Sheriff’s Department. They want them out of there,” Michael Garriga, then the county administrator, said at the time, according to another Times-Tribune article. (The news stories didn’t include a comment from the hospital; Alexander, Baptist’s spokesperson, said she couldn’t comment on practices from years ago because no one who was part of the leadership team then is still around.)

In 2008, the CEO of Parkwood Behavioral Health System, which operates a psychiatric facility in the county, offered to treat people going through the commitment process for $465 per patient per day — many times more than the $25 a day it cost back then to house someone in jail. No contract was ever signed.

Two years later, again aiming to reduce how often people awaiting mental health treatment were jailed, DeSoto County started working with a different community mental health center, Region IV. The number of people held in jail during commitment proceedings fell sharply, but within several years it had risen.

In 2021, the state Department of Mental Health said it would give Region IV money to create a crisis unit in DeSoto, the largest county in the state without one. But the county must provide the building, and it has taken about two years just to move forward with a location, according to meeting minutes.

County officials considered putting the crisis unit in a building a few miles from the hospital and even got an architect to scope out a renovation, according to meeting minutes. By 2023, those plans had been scuttled amid concerns about the cost of renovations and opposition from neighbors, according to Mark Gardner, a county supervisor, and board meeting minutes.

Former Sheriff Bill Rasco said he was told by an alderman for the city of Southaven that residents didn’t want people with mental illness in their neighborhood. Rasco, who served from 2008 through 2023, said he believes the rapidly growing county has had the means to build a facility, but supervisors prioritize paving roads and keeping taxes low. “We build agricultural arenas, walking trails and ballfields, and we let our mental health suffer,” he said.

The county Board of Supervisors inched forward again in February, voting to hire an architect to draw up plans to renovate a different county building. But construction on the 16-bed facility won’t start until spring 2025 at the earliest.

Gardner, who was first elected in 2011, said he has always believed that people with mental illness shouldn’t be jailed, but the Sheriff’s Department and Region IV didn’t propose an alternative until recently. “We need it today,” he said. “I hate that we haven’t been able to find a suitable place till now to put this.”

A year after Sydney Jones’ second psychotic episode, she’s doing better. She hasn’t experienced another mental health crisis. The sight of a police cruiser no longer triggers a panic attack, though she does get anxious when she sees one in her neighborhood.

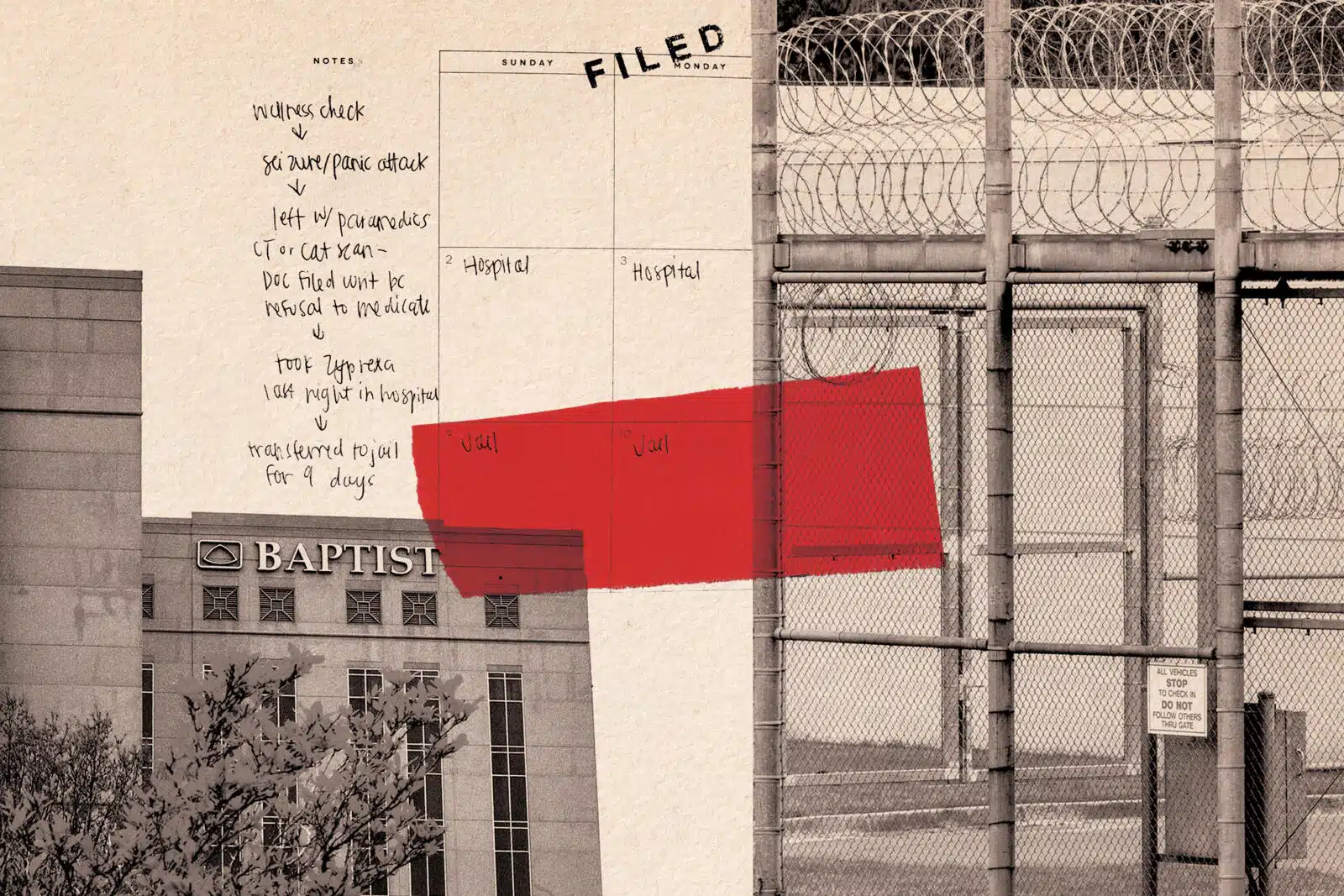

But she wants to remind herself of what she survived to get here, so she keeps mementos. The composition book where she wrote notes during group therapy at the crisis unit. The Bible she read in jail. The planner where she wrote “Hospital” in one square and “Jail” in the next. And two plastic wristbands: The white one identified her as a hospital patient; the yellow one, with her mug shot and booking number, identified her as a prisoner.

How We Reported This Story

To report this story, we obtained DeSoto County Sheriff’s Department logs from 2021 through 2023 that showed when deputies were called to two local hospitals to take people into custody for involuntary commitment proceedings to receive treatment for mental illness or substance abuse. Those logs included nearly 200 calls, mostly to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto.

To determine which calls resulted in jail detentions, we needed to cross-reference the logs with incident reports and county jail dockets. We requested incident reports for about half of calls from 2021 through 2023. Although this sample wasn’t collected at random, we requested records from a range of months to account for possible variations throughout the year. Patients’ names were redacted from incident reports, but by using other identifying information in those reports, we matched 76% of the call logs in our sample to an entry in jail dockets. The remaining calls included not just those for which we couldn’t match an incident report to a jail docket entry, but also those for which there was no incident report or the patient was taken to a crisis unit or a private psychiatric hospital.

Based on that percentage and the volume of calls during the three-year period, we estimated that about 23% of the roughly 650 people jailed during the civil commitment process in DeSoto County had been picked up at a local hospital. Again, the overwhelming majority were taken from Baptist-DeSoto. To ensure that our estimate was conservative and accounted for any variation due to our sample, we characterized this as about one-fifth of civil commitment jail detentions. We shared our preliminary findings with hospital and county officials; no one disputed them.

To determine how the number of people jailed during commitment proceedings in DeSoto County has changed over time, we obtained jail dockets dating back to 2007. We don’t have data for 2009 and 2010 because of a file storage issue at the Sheriff’s Department.

Agnel Philip of ProPublica contributed reporting. Mollie Simon of ProPublica contributed research.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=362139

Mississippi Today

PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership

NEW ALBANY — After five hours in a courtroom where attendees struggled to find standing room, the Mississippi Public Service Commission voted to petition a judge to put the Holly Springs Utility Department into a receivership.

The PSC held the hearing Thursday about a half hour drive west from Holly Springs in New Albany, known as “The Fair and Friendly City.” Throughout the proceedings, members of the PSC, its consultants and Holly Springs officials emphasized there was no precedent for what was going on.

The city of Holly Springs has provided electricity through a contract with the Tennessee Valley Authority since 1935. It serves about 12,000 customers, most of whom live outside the city limits. While current and past city officials say the utility’s issues are a result of financial negligence over many years, the service failures hit a boiling point during a 2023 ice storm where customers saw outages that lasted roughly two weeks as well as power surges that broke their appliances.

Those living in the service area say those issues still occur periodically, in addition to infrequent and inaccurate billing.

“I moved to Marshall County in 2020 as a place for retirement for my husband and I, and it’s been a nightmare for five years,” customer Monica Wright told the PSC at Thursday’s hearing. “We’ve replaced every electronic device we own, every appliance, our well pump and our septic pumps. It has financially broke us.

“We’re living on prayers and promises, and we need your help today.”

Another customer, Roscoe Sitgger of Michigan City, said he recently received a series of monthly bills between $500 and $600.

Following a scathing July report by Silverpoint Consulting that found Holly Springs is “incapable” of running the utility, the three-member PSC voted unanimously on Thursday to determine the city isn’t providing “reasonably adequate service” to its customers. That language comes from a 2024 state bill that gave the commission authority to investigate the utility.

The bill gives a pathway for temporarily removing the utility’s control from the city, allowing the PSC to petition a chancery judge to place the department into the hands of a third party. The PSC voted unanimously to do just that.

Thursday’s hearing gave the commission its first chance to direct official questions at Holly Springs representatives. Newly elected Mayor Charles Terry, utility General Manager Wayne Jones and City Attorney John Keith Perry fielded an array of criticism from the PSC. In his rebuttal, Perry suggested that any solution — whether a receivership or selling the utility — would take time to implement, and requested 24 months for the city to make incremental improvements. Audience members shouted, “No!” as Perry spoke.

“We are in a crisis now,” responded Northern District Public Service Commissioner Chris Brown. “To try to turn the corner in incremental steps is going to be almost impossible.”

It’s unclear how much it would cost to fix the department’s long list of ailments. In 2023, TVPPA — a nonprofit that represents TVA’s local partners — estimated Holly Springs needs over $10 million just to restore its rights-of-way, and as much as $15 million to fix its substations. The department owes another $10 million in debt to TVA as well as its contractors, Brown said.

“The city is holding back the growth of the county,” said Republican Sen. Neil Whaley of Potts Camp, who passionately criticized the Holly Springs officials sitting a few feet away. “You’ve got to do better, you’ve got to realize you’re holding these people hostage, and it’s not right and it’s not fair… They are being represented by people who do not care about them as long as the bill is paid.”

In determining next steps, Silverpoint Principal Stephanie Vavro told the PSC it may be hard to find someone willing to serve as receiver for the utility department, make significant investments and then hand the keys back to the city. The 2024 bill, Vavro said, doesn’t limit options to a receivership, and alternatives could include condemning the utility or finding a nearby utility to buy the service area.

Answering questions from Central District Public Service Commissioner De’Keither Stamps, Vavro said it’s unclear how much the department is worth, adding an engineer’s study would be needed to come up with a number.

Terry, who reminded the PSC he’s only been Holly Springs’ mayor for just over 60 days, said there’s no way the city can afford the repair costs on its own. The city’s median income is about $47,000, roughly $8,000 less than the state’s as a whole.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a factual and balanced account of the situation involving the Holly Springs Utility Department and the Mississippi Public Service Commission. It includes perspectives from various stakeholders, such as city officials, residents, and state commissioners, without showing clear favoritism or ideological slant. The focus is on the practical challenges and financial issues faced by the utility, reflecting a neutral stance aimed at informing readers rather than advocating a particular political viewpoint.

Mississippi Today

Brandon residents want answers, guarantees about data center

Residents of Brandon have raised concerns about the environmental impact and safety of a data center planned for their city.

AVAIO Digital, a Connecticut-based company, announced Aug. 19 that it plans to build a data center in Rankin County. While some celebrated the $6-billion investment and the over $20 million in annual tax revenue it would bring, other residents worry about the data center’s water and power consumption and possible pollution. The 600,000-square-foot facility is expected to be completed by 2027.

‘People genuinely just want answers’

When Nathan Rester first saw the news about the data center, he was immediately concerned. Rester grew up in Brandon and now lives there with his wife and toddler just a few miles from where the data center will be built.

READ MORE: Mississippi Marketplace: Another data center on the way

Rester had followed reports about the air pollution that people in and around Memphis have reported, a result of XAI constructing gas turbines without pollution controls normally used for such turbines. He didn’t want to see what was happening in Memphis happen in Brandon.

His wife, Larkyn Collier, made calls but found the answers unsatisfying.

“ No one could really give a straight answer on how it was being built, what sort of precautions were being taken, whether or not there had been any sort of consideration for utility costs or pollutants or anything like that,” Rester said

In response, Collier and Rester started a petition on change.org that now has over 430 signatures. The petition asks Rankin County leaders to guarantee the data center will not cause such problems. So far they have not received any communication from Rankin or Brandon government officials.

Rester is not completely opposed to the data center being built but he wants the government to guarantee it won’t bring utility bill hikes or pollution.

“ People genuinely just want answers and transparency here. And they want safeguards in place,” Rester said.

The AI boom comes to Mississippi

At their most basic level, data centers store computing equipment. They have been around since the 1940s and power things such as cloud storage. But with the boom in artificial intelligence investment, companies are rapidly constructing data centers across the globe.

The investment bank UBS estimates $375 billion will be spent globally on artificial intelligence in 2025. While this investment has fueled economic and technological growth, data centers have faced skepticism in the communities where they’re built, largely due to the amounts of energy and water they consume and possible pollution they emit.

Mississippi has two large-scale data center projects underway – Compass Datacenters in Meridian and Amazon in Madison County. Including the AVAIO data center, the three will add up to over $26 billion in new capital investment, an unprecedented amount for the state.

Cities and states are embracing data centers because of the potential economic growth, new taxes and innovation they bring.

“This investment is poised to create a lasting, positive impact on the city and the wider region,” Brandon Mayor Butch Lee said in a statement to Mississippi Today. “The project represents a major step forward for Brandon, bringing high-tech jobs and economic growth that will resonate throughout Rankin County and beyond.”

When the property is on the tax rolls and fully up and running, the ad valorem tax will bring in an estimated $23 million in new revenue according to Rankin First, the county’s economic development group. Most of it will go to the local school district.

“ These are not here today. And if we didn’t win this project, we would never see those,” said Garrett Wright, executive director of Rankin First, about tax revenue from the data center.

Rankin First, similar to many economic development groups, is not part of county government and is hired to attract new investment and cultivate existing businesses. It owns the land that the data center will be built on, which has been vacant for around 20 years.

AVAIO is eligible for the state’s data center tax incentive and fee in lieu of property tax. Companies pay a negotiated fee for a set period of time instead of the full property tax. The incentive is designed to encourage economic development. It requires sign off from the county board of supervisors, municipal authorities and Mississippi Development Authority, the state’s economic development agency.

It’s estimated AVAIO will create 60 direct jobs and the Amazon data center 300-400 direct jobs. While data centers create relatively few permanent, direct jobs they create additional jobs in the community. A McKinsey and Company report found that for every direct data center job, approximately 3.5 more jobs are created in the community.

Some residents on social media have wondered whether the data center will negatively impact traffic. Traffic and grade separation of the rail lines have been key conversations as Rankin County has grown. Rankin First acknowledged that AVAIO’s presence will increase traffic but they see it as an opportunity to push for long needed infrastructure improvements.

Rankin First and Brandon have been working with AVAIO for two years and says the company is coming to Brandon, in part, because of the thriving community.

“ The company wants to be a community partner. We see that they’re going to get involved with the local community,” said Regina Todd, assistant director of Rankin First.

Brandon residents want answers

Bailey Henry has lived in Brandon for over a decade. She said that when she read about the new data center on social media, she became concerned.

“ I’ve lived in Mississippi the majority of my life and I was raised to leave things better than you found it,” Henry said. “ And I just don’t think that Mississippi is going to be better off from this.”

Henry is worried about the pressure the data centers will put on the city’s infrastructure, pollution and power demands.

She describes the announcement as “ brief and nonchalant as all the explanations have been. From politicians to people who work for Entergy. It has just been, ‘This is what it is. It’s going to be great. Don’t ask any questions.’”

Henry has made calls to and left voicemails with multiple government offices and has not heard back from any of them.

She’s skeptical, but she hopes she’s wrong.

Brandon concerns echo nationwide conversation

The biggest concerns from residents nationwide over data centers has been potential pollution and increases in utility bills. Across the country, there are stories about data centers driving up energy rates, worsening water shortages, polluting the air and creating a constant noise.

AI data centers demand massive amounts of electricity and run constantly. The average AI data center uses as much electricity as 100,000 households, according to a report from the International Energy Agency.

Another concern is water usage. Data centers need to stay at a specific temperature, and water is one of the most efficient ways to cool the servers. The IEA report found that the average AI data center needs about 528,000 gallons of water every day. For communities that already have water concerns, data centers can exacerbate the problems.

Some communities have blamed the increased demand from data centers for rising electricity bills. While part of these costs may be due to general inflation or paying for infrastructure upgrades, some states are trying to monitor or regulate how households are affected.

A data center’s impact can vary based on the design of the center. But by their very nature they consume a lot of power.

“ AI chips are very power hungry. We’re building a lot of computing capacity, so we need to power all of this,” said Ahmed Saeed, a computer science assistant professor at Georgia Tech.

AVAIO promised “sustainable design,” including rainwater collection and solar panels that would “minimize power demands.” But it’s still unclear what, if any, impact the new data center will have on Rankin County residents.

“ Having clarity on the impact of data centers within the community where they’re building is important,” Saeed said. Saeed believes data centers are here to stay and are key for innovation. But he also thinks there’s a need for more government regulation.

“ They’re not necessarily a negative thing, but on the flip side, in order to make sure that they’re net positive it’s hard to ensure that without some regulation,” Saeed said.

Rankin County’s administrator declined to comment for this story. AVAIO and Brandon Water did not respond to requests for comment.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Brandon residents want answers, guarantees about data center appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a balanced view but leans slightly center-left by emphasizing environmental concerns, community impact, and the need for government transparency and regulation regarding the data center project. It highlights residents’ worries about pollution, utility costs, and infrastructure strain, while also acknowledging economic benefits and job creation. The focus on environmental and social accountability alongside economic development aligns with a center-left perspective that values both growth and sustainability.

Mississippi Today

Democratic DA Scott Colom announces U.S. Senate run against Hyde-Smith

Scott Colom, a Democratic district attorney in north Mississippi, announced today that he will run for the U.S. Senate next year against incumbent Republican Cindy Hyde-Smith.

Colom’s entrance into the race is likely to spark a long and expensive battle for the seat, with both national parties expected to spend millions on the race in the Magnolia State.

Chuck Schumer, the Senate’s Democratic leader from New York, told the New York Times he wants to help elect a Democrat in Mississippi. But the Republican Party is almost certain to defend its ironclad grip on Mississippi, a state where both U.S. Senate seats have been held by the GOP since 1989.

In an interview with Mississippi Today ahead of his announcement, Colom said he intends to cast Hyde-Smith’s voting record as prioritizing “D.C. politics” instead of hard-working Mississippians, including her vote for the “One Big Beautiful Bill” that slashed social safety net programs and provided tax cuts for the wealthy.

“Mississippi needs a senator who’s going to put Mississippi first,” Colom said.

But Colom faces an uphill battle. He’s a Democrat running in Mississippi, with one of the most reliably conservative electorates in the nation.

Mississippi last elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 1982, when it reelected John Stennis. A majority of Mississippians have voted for the Republican nominee for president since 1980.

Still, Colom said he can crack the GOP’s stronghold in the state because he has experience with pitching moderate and progressive solutions to a more conservative electorate, as he did when he defeated long-serving incumbent Forrest Allgood, an independent, for district attorney in 2015.

“At the time, people didn’t think I could win the DA’s race,” Colom said.

A native of Columbus, Colom is the elected district attorney of the 16th Circuit Court District, which includes Lowndes, Oktibbeha, Clay and Noxubee counties. He is the first Black DA for the district.

He first won that election by casting his opponent as an incredibly harsh prosecutor who was more concerned with obtaining stiff sentences for convicted criminals than true rehabilitation. After Colom took office, he said he focused his office’s efforts on tackling violent crime and promoting alternative sentencing for nonviolent offenders.

“I have faith that the truth always sees through if you get the message out, speak with conviction and lead with your values,” Colom said. “That’s my plan. I want to speak with my values.”

For example, Colom said he would push for legislation that raises the nation’s minimum wage and exempts law enforcement officers and public school teachers from paying federal income taxes.

This may be the first time the two have competed head-to-head, but it will not be the first time Colom and Hyde-Smith have butted heads. Former President Joe Biden in 2023 nominated Colom to a vacant federal judicial seat in northern Mississippi, but Hyde-Smith thwarted the nomination.

Despite support for Colom from Roger Wicker, Mississippi’s senior U.S. senator, Hyde-Smith was able to block his nomination because of a longstanding tradition in the U.S. Senate that requires senators from a nominee’s home state to submit “blue slips” if they approve of the candidate.

Hyde-Smith never returned one of these slips for Colom. If both senators don’t submit a blue slip, the nominee typically does not advance to a confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Hyde-Smith, at her reelection launch last week, mentioned her opposition to Colom’s elevation to the federal bench.

“He thought he was going to be a federal judge, and I blocked him,” Hyde-Smith said to applause.

Colom is the first Democrat to announce his candidacy for the Senate seat. Ty Pinkins, an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate in 2024, has declared he’s also running for the Senate again in 2026 as an independent.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Democratic DA Scott Colom announces U.S. Senate run against Hyde-Smith appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article presents a factual overview of Democratic candidate Scott Colom’s Senate run against Republican Cindy Hyde-Smith, highlighting Colom’s progressive policy positions such as raising the minimum wage and critiquing Hyde-Smith’s voting record on social safety net cuts. While it includes perspectives from both sides and contextualizes Mississippi’s conservative political landscape, the emphasis on Colom’s values and policy proposals, along with critical framing of Hyde-Smith’s record, suggests a slight lean toward a center-left viewpoint. The tone remains largely informative without overt partisan language.

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

DEI, campus culture wars spark early battle between likely GOP rivals for governor in Mississippi

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

‘They broke us down’: New Orleans teachers, fired after Katrina, reflect on lives upended

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Alabama state grocery tax to fall 1% on Monday

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

Missouri joins dozens of states in eliminating ‘luxury’ tax on diapers, period products

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed4 days ago

Tennessee ranks near the top for ICE arrests

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Trump proposed getting rid of FEMA, but his review council seems focused on reforming the agency

-

Local News6 days ago

Today in History: September 1, Titanic wreckage found

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed7 days ago

Warm and Mainly Dry Labor Day