Mississippi Today

The Emmett Till lynching has seen more than its share of liars. Is Tim Tyson one of them?

Award-winning historian Tim Tyson swears he heard admissions regarding Emmett Till’s lynching and another racial murder.

Admissions that weren’t recorded. Admissions that no one else heard. Admissions that he began hearing when he was 10.

“The question is not whether Tim Tyson fooled us once,” said Devery Anderson, author of “Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement.” “The question is whether he fooled us twice — and got away with it.”

Tyson has said he heard these admissions. He didn’t respond to requests for comments on the Till matter, but he has previously spoken to me, the FBI and others. All these are noted.

Tyson’s 2017 book, “The Blood of Emmett Till,” lit the bomb that exploded around the world with this claim: The white woman at the center of the Emmett Till case, Carolyn Bryant Donham, had admitted she lied when she testified that he had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities.

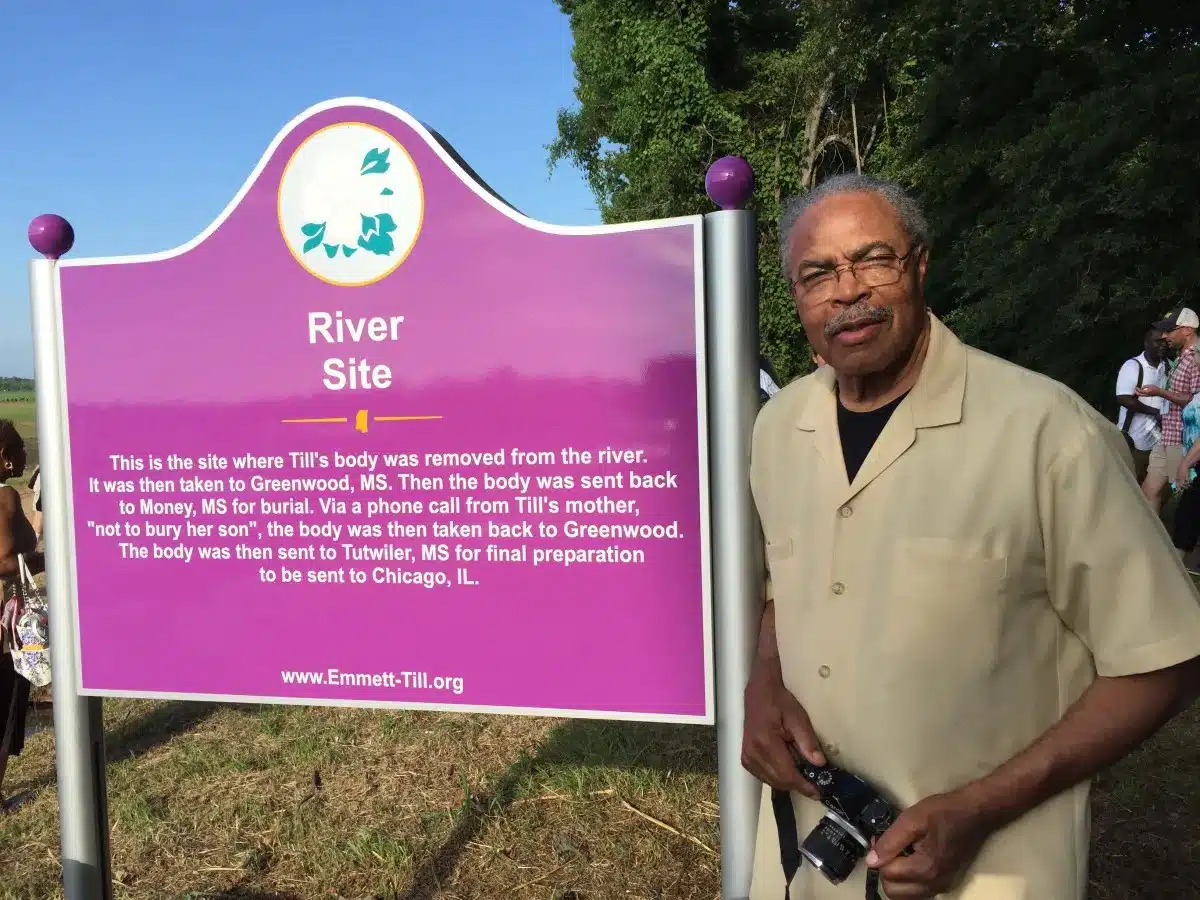

For some in the Till family, such as his cousin, the Rev. Wheeler Parker, the revelation represented the hope of clearing his cousin’s name. “I was elated,” he said.

He had longed to hear Donham say she lied about Till and planned to forgive her when she did, said the longtime pastor. “I was raised to believe deeply in forgiveness. If you don’t forgive, God won’t forgive you.”

For some in the Till family, the revelation raised hopes of a possible prosecution. His cousin, Deborah Watts, said there should be “a revisiting of the evidence in light of this revelation,” and Bennie Thompson, the Democratic congressman for the Mississippi Delta, called for an investigation, saying this represented “an opportunity to bring some justice to an innocent 14-year-old boy.”

For Till’s cousin, Ollie Gordon, the revelation sounded like a ruse. She saw no logic, she said, in Donham sharing such information with someone she hardly knew.

“I thought, ‘Oh, here we go. This man wants to sell his book,’” she said. “He knew if he put that lie out, that was going to help him sell the book.”

The fact that Tyson spoke to Donham but no one in the Till family reflects his mindset, she said. “If you want first-hand information, you go to the family. If you want to write what you want to write, you just bypass the family.”

What Tyson did to the Till family is nothing new, she said. “People have made money off the blood of Emmett Till and the backs of the Till family. They’re all chasing the dollar. They don’t care how they get it.”

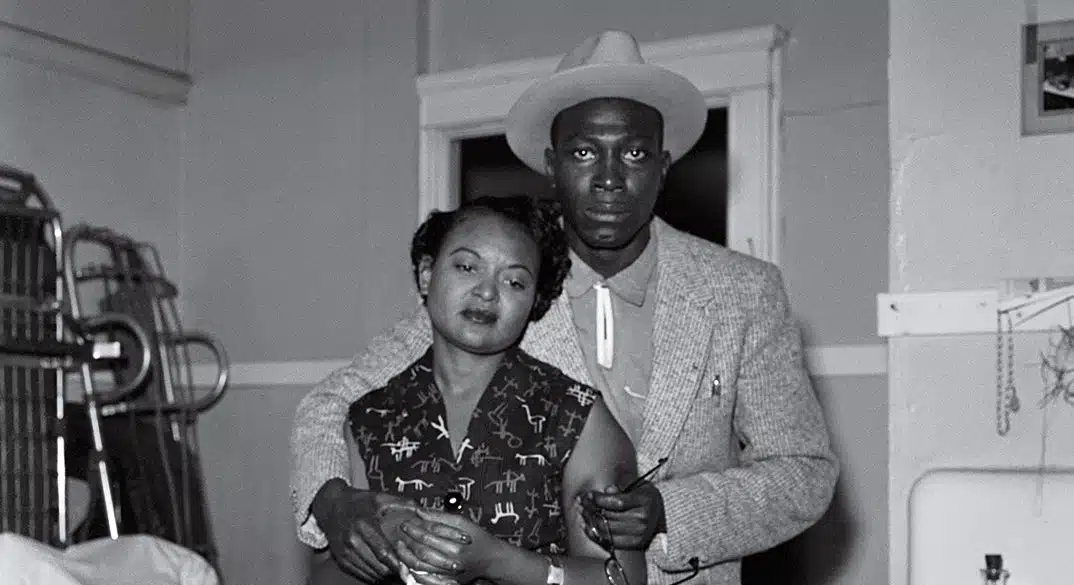

Parker still remembers the night of Aug. 28, 1955, when two men with guns stormed the Mississippi Delta home where he and his cousin, Emmett Till, were staying. He and Till had come from Chicago to visit relatives.

It was past 2 a.m., “as dark as a thousand midnights,” Parker said, when he heard angry voices from the gloom.

A flashlight shone down the hall, and he shut his eyes, ready to hear the shots that would steal his life. He trembled as he prayed, his 16 years flitting across his mind, he said. “I knew I wasn’t right with God.”

He heard the men say they “wanted the fat boy” that had “done the talking” at Bryant’s Grocery.

Before long, their steps receded and then their voices. They were gone, and so was his cousin, Emmett, whom kidnappers hauled to a remote barn and began beating.

After the first light came, Parker fled Mississippi.

For 30 years, he wasn’t asked about what he had seen, but in the decades since, he has spoken out.

While visiting one school, a white student told Parker that Till had “misbehaved” inside the store and got what he deserved.

“What could he have done to deserve that?” Parker said he responded. “I know he didn’t do anything.”

He and another cousin said they never saw Till do or say anything to Donham inside the store. All Till did was whistle at her after she walked outside, they said.

Several nights later, Till’s murderers executed their own judgment, Parker said. “They killed him for what? A whistle?”

Till’s torture lasted much of the night, and witnesses heard him screaming past dawn. By the time the sun began to peek over the horizon, his cries became fainter.

Silence followed.

Till’s killers tried to bury their evil deeds by tying a 75-pound gin fan around his neck and tossing his body into water that fed into the Tallahatchie River.

The next day, when a deputy questioned two of the killers, J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant, they admitted they had kidnapped Till, but insisted they had released him unharmed. Days later, his body bobbed back to the river’s surface.

Sheriff Clarence Strider tried to bury Till’s brutalized body in a local cemetery to conceal the evil deed, but when his mother found out, she demanded his return to Chicago, where she opened his casket. “I wanted the world,” she said, “to see what I had seen.”

The lies continued after his funeral.

After arrests in the case, Bryant’s wife, Donham, told the defense lawyer that Till came into Bryant’s Grocery, grabbed her hand, asked for a date and said “goodbye” as he left.

But weeks later, the lawyer announced to reporters that Till had “mauled” Donham, and she echoed that lie from the witness stand. With the jury out of the courtroom, she claimed that Till had grabbed her around the waist, told her “you needn’t be afraid of me,” and said he had sex with white women before.

The sheriff got in on the lies, too. After Till was found, the sheriff told reporters the body had only been in the river a few days, released the body to a Black mortician and filled out a death certificate for Till.

But by the time the trial began, he had become a witness for the defense. He testified that the body had been in the water for at least 10 days and that he couldn’t tell the color of the skin — only that it was human. His words backed the incredulous defense claim that Till was still alive and that the NAACP had planted a cadaver in the river. (Five decades later, an autopsy and a DNA test proved that Till’s body was the one in his grave.)

The all-white jury acquitted the two men, despite believing they had killed Till, according to interviews the jurors gave Stephen Whitaker, who researched the case for his master’s thesis.

If those lies weren’t enough, journalist William Bradford Huie concealed the identities of other killers with his Look magazine article.

Huie told his editor that four men had taken part in the “torture-and-murder party,” but when the editor insisted on getting legal releases from all four, the murder party shrunk to two. (One trial witness, Willie Reed, identified four white men riding in the cab of the truck while three Black men held Till in the back.)

As for Huie, he had dreams of a Hollywood film and paid Till’s killers $3,150 for their rights.

The idea of Huie making “a deal with the murderers” angered Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, and her attorney sent a cease and desist letter to United Artists, said Till documentary filmmaker Keith Beauchamp.

Huie’s 1956 article became gospel in the Till case until a new FBI investigation almost a half century later. Dale Killinger, who conducted that probe, said “the damage from those lies was deeper and broader than just Till’s murder.”

Three months before Till was killed, the Rev. George Lee was assassinated because he helped Black Mississippians register to vote in Belzoni. The sheriff claimed the shotgun pellets found in Lee’s face were loose fillings from his teeth.

Lamar Smith was gunned down in broad daylight on the courthouse lawn in Brookhaven. Despite the killer being covered in blood, the sheriff maintained there were no witnesses.

Killinger said these types of killings — and the lies that made them possible — “perpetuated generational trauma.”

By age 7, Tim Tyson was already spinning yarns.

He and his best friend “would lie there in the dark in the twin beds, and I would tell him stories, making them up as I went,” Tyson wrote in his memoir, “Blood Done Signed My Name.”

With each concocted tale, his friend cheered him on. “His fierce and unfeigned enthusiasm for these rambling odysseys,” Tyson wrote, “was like a drug to me.”

His friend even coined a name for them: “Tim’s Tall Tales.”

By the time Tyson telephoned me in 2008, he was already mesmerizing audiences with his stories of growing up in Oxford, North Carolina, and his memoir was being made into a movie.

Over lunch at Hal & Mal’s in Jackson, Tyson, who serves as a senior research scholar for the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, told me he landed an interview with Donham, the first interview I had ever heard of her giving to a historian. I congratulated him.

We talked about the Till case and much of the lore surrounding it.

Months later, we met in Jackson, he said he had finished talking with her. He told me her story mirrored her testimony, where she claimed Till had mauled her.

“You know she lied, don’t you?” I asked.

The statement surprised him, and afterward, I mailed him a copy of the statement she had made to the defense lawyer, where she mentioned nothing about Till grabbing her or talking about having sex with her.

He used that statement in his book and tried to talk with Donham again. She turned him down.

Much to my surprise, “The Blood of Emmett Till” hit the shelves in 2017 with the claim that Donham had admitted to Tyson that she had lied when she testified that Till had grabbed her around the waist and uttered obscenities.

News of the revelation spread like wildfire, first through top publications and television stations, before hitting Black radio, television, websites and word of mouth. “The Blood of Emmett Till” shot onto The New York Times Bestseller List and won the Robert F. Kennedy Award.

Calls arose for her prosecution, and the Justice Department began to look at the Till case again.

Questions soon surfaced. A source told me that Donham’s family was saying she didn’t recant, and I telephoned her then-daughter-in-law, Marsha Bryant, who said she was present the whole time and never heard the quotation Tyson attributed to Donham. Bryant said she had a copy of the transcript and the quote wasn’t in it.

When I reached out to Tyson in 2018, he confirmed he didn’t have the bombshell quote on tape, saying he was still setting up his recorder.

The book “Till” opens with Donham drinking coffee and serving Tyson a slice of pound cake. “She had never opened her door to a journalist or historian, let alone invited one for cake and coffee,” he wrote.

Bryant said Tyson actually brought the cake himself, and after the interview, he took it back with him.

Tyson told me his recorder wasn’t working when Donham said, “They’re all dead now anyway,” so he snatched up his notebook, began scribbling notes and heard her recantation.

But when the FBI began to investigate the matter, he gave investigators multiple accounts: that his recorder wasn’t working, that his recording was lost, that he didn’t realize he didn’t have her recantation on tape until much later.

Tyson wrote that Donham handed him a trial transcript and the memoir. Bryant disputed that, saying Donham never handed Tyson anything.

Tyson wrote that after Donham handed him the transcript, she said, “That part is not true.”

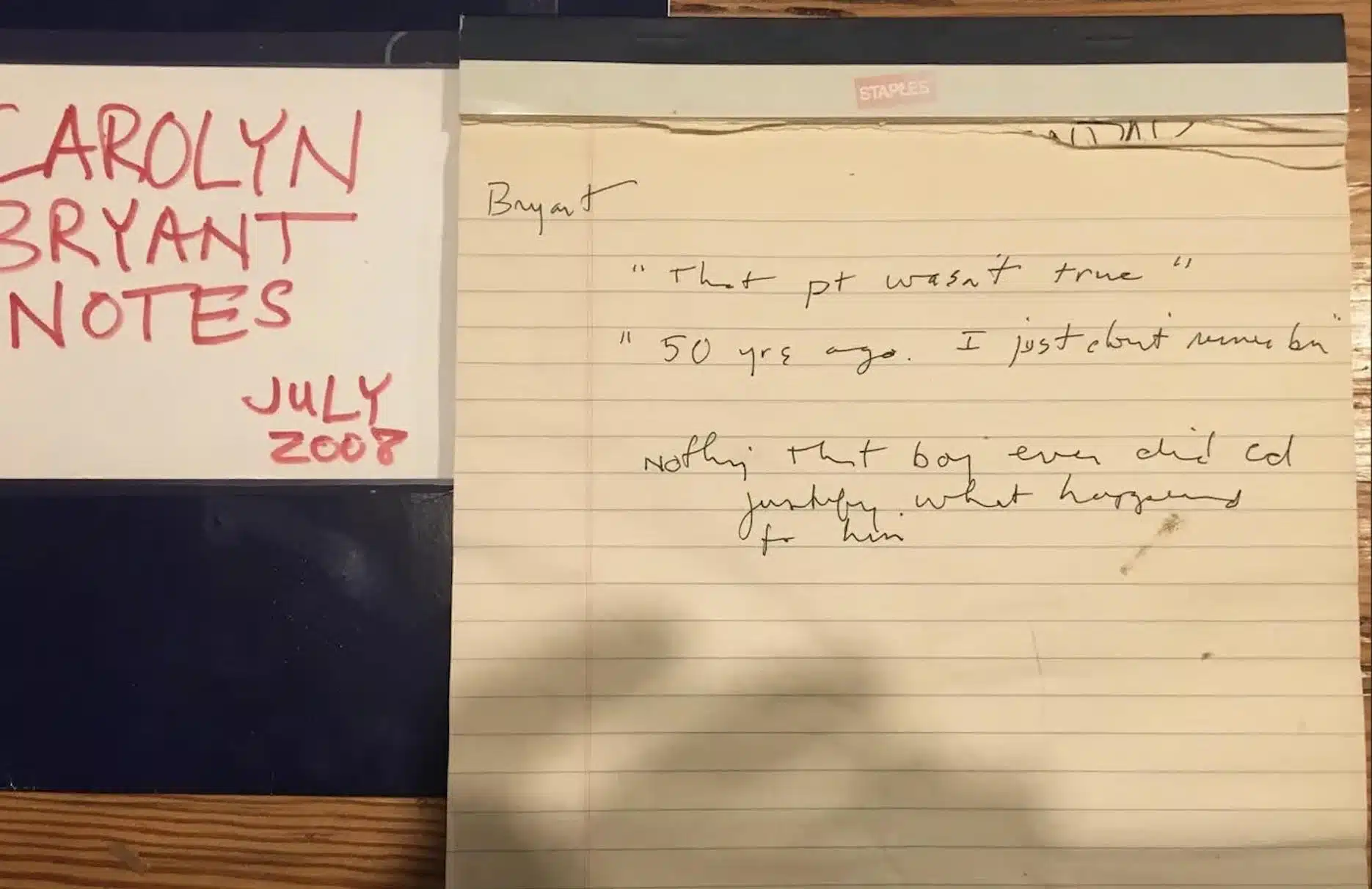

Tyson emailed me a photograph of his undated notes, which he shared with the FBI: “That pt wasn’t true. … 50 yrs ago. I just don’t remember. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

The way the quote appears in the “Till” book (italics show the words missing from the notes): “They’re all dead now anyway. … I want to tell you. Honestly, I just don’t remember. It was 50 years ago. You tell these stories for so long that they seem true, but that part is not true. … Nothing that boy ever did could justify what happened to him.”

Tyson told me Donham’s recantation took place in July 2008.

The problem with that date? He hadn’t met her yet, according to emails he wrote in August 2008 to her family.

Asked by email how he could have interviewed Donham in July 2008 when he had yet to meet her then, Tyson did not reply.

Tyson said Bryant didn’t take exception to “any of the facts” in the book, but was upset about people posting pictures of their house on the Internet.

Bryant told me she did object and shared an email with the FBI that she had sent Tyson, wanting to know why he was saying Donham had admitted she lied.

Bryant wrote Donham’s memoir, “I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle: The Story of Carolyn Bryant Donham,” and shared a copy with Tyson, who said in an August 2008 email that the work would prove “invaluable to history.”

Bryant said Tyson agreed to act as an editor for the book — a claim he told me was “bullsh–.”

But emails and edited versions of Donham’s memoir show Tyson edited the book, suggested revisions and rewrote the preface. The Department of Justice’s report also noted Tyson’s editing.

In a note Tyson put at the top of Donham’s memoir on March 6, 2009, he wrote, “Dear Marsha and Carolyn: I am sorry to take so long getting this back to you. I enjoyed reading it. But editing is hard work …

“Read over my edits and comments. I think they may suggest to you some of the broad outlines for another revision. When you finish another version — there will be several more, which is the nature of the publication process — you may feel free to send it to me. … You’ve done a great job thus far.”

He emailed Bryant and asked her to list him as “editor of the final project, since I am a professional scholar who has a boss (the dean) who wants to know how I spent my time and energy. ‘Editor’ can go on my annual report and suggest to the dean that I don’t just sit around and drink coffee and read the newspaper, regardless of what my wife and children might report to the contrary.”

Bryant believes it was “unethical” for him to serve as her editor and then take passages from her book to use in his own publication, she said. “He denied being my editor. It’s pretty damn obvious he was my editor.”

She said she is even angrier that Tyson recently made public a copy of her book, she said. “It appears to me that he is trying to inject himself into the Emmett Till story again by making sure he’s front and center.”

Tyson denied to the FBI that he ever agreed to assist Bryant in getting the memoir published, but in his first email to the family in August 2008, he wrote, “ think you should try to publish this book, and I will be glad to offer what help I can, including introducing you to my agent.”

At no point in Donham’s memoir, the two interviews she gave Tyson or the interviews she gave the FBI does she say she recanted. In fact, in her memoir, she doubled down on the claim that Till attacked her. She even made the head-scratching claim that when Till’s kidnappers asked her if he was the one who attacked her in the store, she refused to say — only for Till to identify himself to his kidnappers.

One of the biggest questions the FBI had for Tyson was why, after Donham recanted, he never asked her to repeat her statement or quiz her about this contradiction. He told the FBI that he didn’t want to interrupt the “flow” of the conversation, but he interrupted her at other times to clarify points, the Justice Department noted in its report closing the Till case.

Tyson had other opportunities in his editing of the memoir. He wrote many suggestions and questions about the book, but he never asked Donham a single question about what he claimed was her recantation.

The FBI asked Tyson why he failed to share this important evidence with authorities for nearly a decade, and he replied that he thought the case was closed.

When investigators interviewed Tyson, “rather than obtaining other corroborating evidence to support Tyson’s claim that … [Donham] offered a recantation,” the report said, “investigators instead identified numerous inconsistencies in Tyson’s account that raised questions about the credibility of his account of the interviews.”

In closing the Till case on Dec. 6, 2021, the Justice Department said, “Tyson’s account lacks credibility,” citing his “shifting explanations to FBI investigators …, the questionable nature of his relationship with [Donham], and his financial motives.”

Sixteen months later, Donham died — and with it any hope of a prosecution in the Till case.

After discovering these things about “The Blood of Emmett Till,” I reached out to a historian, who told me, “You know there were problems with Tyson’s previous book.”

That was news to me. Researcher Brandon Arvesen and I dove deeper into “Blood Done Sign My Name.”

The book centers on the May 11, 1970 killing of Henry Marrow, a 23-year-old Black man killed by members of the Teel family. After his slaying, Robert and Larry Teel turned themselves in to authorities, who moved them from a local jail to a prison in Raleigh 40 miles away, according to newspaper accounts.

The book opens with Tyson claiming his 10-year-old friend, Gerald Teel, told him in person on the evening of May 12, 1970, that his father, Robert, and his brother, Roger, shot “a n—–” last night in Oxford, North Carolina.

One problem with this claim? The Teel family may have already left town for safety reasons to Mount Olive, more than 100 miles away, according to newspaper reports.

The Feb. 21, 1971, Durham Herald-Sun newspaper says Teel’s sons “did not return to school in Oxford after May 11. Instead they were enrolled in classes in Mount Olive where they finished out the term.”

Tyson did not reply to calls and emails regarding this question.

This is far from the only issue with the book. “Name” has some faulty footnotes, wrong details, wrong dates for events and wrong quotations.

For instance, Tyson quoted Black businessman James Gregory as saying, “Even some black folks want to believe we’ve made a lot of progress in race relations, but deep down they know things are bad.”

Tyson attributed the quote to the May 29, 1970, issue of the Raleigh News and Observer. The actual quote from Gregory, published a day earlier, said, “Outsiders are responsible for all of this.”

During their murder trial, Robert and Larry Teel claimed self-defense.

Robert Teel’s stepson, Roger Oakley, became the defense’s surprise witness, claiming he was the one who fired the fatal shot, but accidentally, of course. A jury acquitted the Teels, and a Raleigh News and Observer editorial called the verdict a “sham and mockery.”

Thirteen years later, Tyson interviewed the father, Robert Teel, for a master’s thesis.

The Teel family shared what they say is a handwritten contract that Tyson signed and gave them at the time: “In exchange for above cooperation, Mr. Tyson will, upon graduation from law school, represent Mr. [Robert] Teel as his legal counsel in a legal action of Mr. Teel’s choice, without retainer’s fee, on a 50%/50% contractual basis, … immediately upon graduation to perform above legal action in a prompt manner.” (Tyson has a doctorate in history, but his Duke University biography makes no mention of law school.)

After Tyson wrote “Blood Done Sign My Name,” he donated a copy of his master’s thesis to the Thornton Library in Oxford and said in the author’s note that someone had torn out several pages about Marrow’s killing, “presumably to prevent other people from reading them.”

The thesis has since disappeared from the library, but Mississippi Today has obtained a copy of the entire thesis, including the missing pages, which differs from “Name.”

In his thesis, Tyson wrote that Marrow “walked down to Freeman’s store and returned with a six pack of Country Club Malt Liquor,” but in “Name,” Tyson wrote that Marrow went to Teel’s convenience store to get a big Pepsi and something to eat.

Robert Teel ran a car wash, according to newspaper articles at the time. He also operated a barber shop, a coin-operated laundromat and a cycle shop, according to the Feb. 16, 1971, Oxford Public Ledger. The newspaper mentions nothing about a convenience store, and Teel’s son, Larry, said they never had one.

As with his Till book, Tyson didn’t interview the victim’s family.

When Till’s cousin, Parker, found out that Donham, the white woman at the center of the case, denied she had ever recanted and there was no recording, his heart sank, he said. “It was a blow.”

Tyson “did some big lying,” said Parker, whose book with Chris Benson, “A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on the Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till,” was published in January. “He said he had a recorder, but everything is missing.”

Tyson has defended the recantation, telling The New York Times that he took detailed notes: “Carolyn started spilling the beans before I got the recorder going. I documented her words carefully. My reporting is rock solid.”

Till’s cousin, Gordon, said for the author to make things right to the Till family, he would need to apologize for the harm he has caused them. “He would have to admit he fabricated this,” she said.

Tyson did not reply to a request for comment on the Till family’s remarks.

After the release of his Till book in 2017, CBS This Morning interviewed Tyson about the bombshell quote from Donham, whom he suggested had recanted because she was remorseful.

“We’re not punished for our sins; we’re punished by our sins,” he told Gayle King. “Nobody ever gets away with anything.”

Researcher Brandon Arvesen contributed to this report.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing

TYLERTOWN — As an ominous storm approached Buddy Anthony’s one-story brick home, he took shelter in his new Ford F-250 pickup parked under a nearby carport.

Seconds later, a tornado tore apart Anthony’s home and damaged the truck while lifting it partly in the air. Anthony emerged unhurt. But he had to replace his vehicle with a used truck that became his home while waiting for President Donald Trump to issue a major disaster declaration so that federal money would be freed for individuals reeling from loss. That took weeks.

“You wake up in the truck and look out the windshield and see nothing. That’s hard. That’s hard to swallow,” Anthony said.

Disaster survivors are having to wait longer to get aid from the federal government, according to a new Associated Press analysis of decades of data. On average, it took less than two weeks for a governor’s request for a presidential disaster declaration to be granted in the 1990s and early 2000s. That rose to about three weeks during the past decade under presidents from both major parties. It’s taking more than a month, on average, during Trump’s current term, the AP found.

The delays mean individuals must wait to receive federal aid for daily living expenses, temporary lodging and home repairs. Delays in disaster declarations also can hamper recovery efforts by local officials uncertain whether they will receive federal reimbursement for cleaning up debris and rebuilding infrastructure. The AP collaborated with Mississippi Today and Mississippi Free Press on the effects of these delays for this report.

“The message that I get in the delay, particularly for the individual assistance, is that the federal government has turned its back on its own people,” said Bob Griffin, dean of the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity at the University at Albany in New York. “It’s a fundamental shift in the position of this country.”

The wait for disaster aid has grown as Trump remakes government

The Federal Emergency Management Agency often consults immediately with communities to coordinate their initial disaster response. But direct payments to individuals, nonprofits and local governments must wait for a major disaster declaration from the president, who first must receive a request from a state, territory or tribe. Major disaster declarations are intended only for the most damaging events that are beyond the resources of states and local governments.

Trump has approved more than two dozen major disaster declarations since taking office in January, with an average wait of almost 34 days after a request. That ranged from a one-day turnaround after July’s deadly flash flooding in Texas to a 67-day wait after a request for aid because of a Michigan ice storm. The average wait is up from a 24-day delay during his first term and is nearly four times as long as the average for former Republican President George H.W. Bush, whose term from 1989-1993 coincided with the implementation of a new federal law setting parameters for disaster determinations.

The delays have grown over time, regardless of the party in power. Former Democratic President Joe Biden, in his last year in office, averaged 26 days to declare major disasters — longer than any year under former Democratic President Barack Obama.

FEMA did not respond to the AP’s questions about what factors are contributing to the trend.

Others familiar with FEMA noted that its process for assessing and documenting natural disasters has become more complex over time. Disasters have also become more frequent and intense because of climate change, which is mostly caused by the burning of fuels such as gas, coal and oil.

The wait for disaster declarations has spiked as Trump’s administration undertakes an ambitious makeover of the federal government that has shed thousands of workers and reexamined the role of FEMA. A recently published letter from current and former FEMA employees warned the cuts could become debilitating if faced with a large-enough disaster. The letter also lamented that the Trump administration has stopped maintaining or removed long-term planning tools focused on extreme weather and disasters.

Shortly after taking office, Trump floated the idea of “getting rid” of FEMA, asserting: “It’s very bureaucratic, and it’s very slow.”

FEMA’s acting chief suggested more recently that states should shoulder more responsibility for disaster recovery, though FEMA thus far has continued to cover three-fourths of the costs of public assistance to local governments, as required under federal law. FEMA pays the full cost of its individual assistance.

Former FEMA Administrator Pete Gaynor, who served during Trump’s first term, said the delay in issuing major disaster declarations likely is related to a renewed focus on making sure the federal government isn’t paying for things state and local governments could handle.

“I think they’re probably giving those requests more scrutiny,” Gaynor said. “And I think it’s probably the right thing to do, because I think the (disaster) declaration process has become the ‘easy button’ for states.”

The Associated Press on Monday received a statement from White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson in response to a question about why it is taking longer to issue major natural disaster declarations:

“President Trump provides a more thorough review of disaster declaration requests than any Administration has before him. Gone are the days of rubber stamping FEMA recommendations – that’s not a bug, that’s a feature. Under prior Administrations, FEMA’s outsized role created a bloated bureaucracy that disincentivized state investment in their own resilience. President Trump is committed to right-sizing the Federal government while empowering state and local governments by enabling them to better understand, plan for, and ultimately address the needs of their citizens. The Trump Administration has expeditiously provided assistance to disasters while ensuring taxpayer dollars are spent wisely to supplement state actions, not replace them.”

In Mississippi, frustration festered during wait for aid

The tornado that struck Anthony’s home in rural Tylertown on March 15 packed winds up to 140 mph. It was part of a powerful system that wrecked homes, businesses and lives across multiple states.

Mississippi’s governor requested a federal disaster declaration on April 1. Trump granted that request 50 days later, on May 21, while approving aid for both individuals and public entities.

On that same day, Trump also approved eight other major disaster declarations for storms, floods or fires in seven other states. In most cases, more than a month had passed since the request and about two months since the date of those disasters.

If a presidential declaration and federal money had come sooner, Anthony said he wouldn’t have needed to spend weeks sleeping in a truck before he could afford to rent the trailer where he is now living. His house was uninsured, Anthony said, and FEMA eventually gave him $30,000.

In nearby Jayess in Lawrence County, Dana Grimes had insurance but not enough to cover the full value of her damaged home. After the eventual federal declaration, Grimes said FEMA provided about $750 for emergency expenses, but she is now waiting for the agency to determine whether she can receive more.

“We couldn’t figure out why the president took so long to help people in this country,” Grimes said. “I just want to tie up strings and move on. But FEMA — I’m still fooling with FEMA.”

Jonathan Young said he gave up on applying for FEMA aid after the Tylertown tornado killed his 7-year-old son and destroyed their home. The process seemed too difficult, and federal officials wanted paperwork he didn’t have, Young said. He made ends meet by working for those cleaning up from the storm.

“It’s a therapy for me,” Young said, “to pick up the debris that took my son away from me.”

Historically, presidential disaster declarations containing individual assistance have been approved more quickly than those providing assistance only to public entities, according to the AP’s analysis. That remains the case under Trump, though declarations for both types are taking longer.

About half the major disaster declarations approved by Trump this year have included individual assistance.

Some people whose homes are damaged turn to shelters hosted by churches or local nonprofit organizations in the initial chaotic days after a disaster. Others stay with friends or family or go to a hotel, if they can afford it.

But some insist on staying in damaged homes, even if they are unsafe, said Chris Smith, who administered FEMA’s individual assistance division under three presidents from 2015-2022. If homes aren’t repaired properly, mold can grow, compounding the recovery challenges.

That’s why it’s critical for FEMA’s individual assistance to get approved quickly — ideally, within two weeks of a disaster, said Smith, who’s now a disaster consultant for governments and companies.

“You want to keep the people where they are living. You want to ensure those communities are going to continue to be viable and recover,” Smith said. “And the earlier that individual assistance can be delivered … the earlier recovery can start.”

In the periods waiting for declarations, the pressure falls on local officials and volunteers to care for victims and distribute supplies.

In Walthall County, where Tylertown is, insurance agent Les Lampton remembered watching the weather news as the first tornado missed his house by just an eighth of a mile. Lampton, who moonlights as a volunteer firefighter, navigated the collapsed trees in his yard and jumped into action. About 45 minutes later, the second tornado hit just a mile away.

“It was just chaos from there on out,” Lampton said.

Walthall County, with a population of about 14,000, hasn’t had a working tornado siren in about 30 years, Lampton said. He added there isn’t a public safe room in the area, although a lot of residents have ones in their home.

Rural areas with limited resources are hit hard by delays in receiving funds through FEMA’s public assistance program, which, unlike individual assistance, only reimburses local entities after their bills are paid. Long waits can stoke uncertainty and lead cost-conscious local officials to pause or scale-back their recovery efforts.

In Walthall County, officials initially spent about $700,000 cleaning up debris, then suspended the cleanup for more than a month because they couldn’t afford to spend more without assurance they would receive federal reimbursement, said county emergency manager Royce McKee. Meanwhile, rubble from splintered trees and shattered homes remained piled along the roadside, creating unsafe obstacles for motorists and habitat for snakes and rodents.

When it received the federal declaration, Walthall County took out a multimillion-dollar loan to pay contractors to resume the cleanup.

“We’re going to pay interest and pay that money back until FEMA pays us,” said Byran Martin, an elected county supervisor. “We’re hopeful that we’ll get some money by the first of the year, but people are telling us that it could be [longer].”

Lampton, who took after his father when he joined the volunteer firefighters 40 years ago, lauded the support of outside groups such as Cajun Navy, Eight Days of Hope, Samaritan’s Purse and others. That’s not to mention the neighbors who brought their own skid steers and power saws to help clear trees and other debris, he added.

“That’s the only thing that got us through this storm, neighbors helping neighbors,” Lampton said. “If we waited on the government, we were going to be in bad shape.”

Lieb reported from Jefferson City, Missouri, and Wildeman from Hartford, Connecticut.

Update 98/25: This story has been updated to include a White House statement released after publication.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical view of the Trump administration’s handling of disaster declarations, highlighting delays and their negative impacts on affected individuals and communities. It emphasizes concerns about government downsizing and reduced federal support, themes often associated with center-left perspectives that favor robust government intervention and social safety nets. However, it also includes statements from Trump administration officials defending their approach, providing some balance. Overall, the tone and framing lean slightly left of center without being overtly partisan.

Mississippi Today

Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina

The 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina slamming the Mississippi Gulf Coast has come and gone, rightfully garnering considerable media attention.

But still undercovered in the 20th anniversary saga of the storm that made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, and caused unprecedented destruction is the role that a worm farmer from northeast Mississippi played in helping to revitalize the Coast.

House Speaker Billy McCoy, who died in 2019, was a worm farmer from the Prentiss, not Alcorn County, side of Rienzi — about as far away from the Gulf Coast as one could be in Mississippi.

McCoy grew other crops, but a staple of his operations was worm farming.

Early after the storm, the House speaker made a point of touring the Coast and visiting as many of the House members who lived on the Coast as he could to check on them.

But it was his action in the forum he loved the most — the Mississippi House — that is credited with being key to the Coast’s recovery.

Gov. Haley Barbour had called a special session about a month after the storm to take up multiple issues related to Katrina and the Gulf Coast’s survival and revitalization. The issue that received the most attention was Barbour’s proposal to remove the requirement that the casinos on the Coast be floating in the Mississippi Sound.

Katrina wreaked havoc on the floating casinos, and many operators said they would not rebuild if their casinos had to be in the Gulf waters. That was a crucial issue since the casinos were a major economic engine on the Coast, employing an estimated 30,000 in direct and indirect jobs.

It is difficult to fathom now the controversy surrounding Barbour’s proposal to allow the casinos to locate on land next to the water. Mississippi’s casino industry that was birthed with the early 1990s legislation was still new and controversial.

Various religious groups and others had continued to fight and oppose the casino industry and had made opposition to the expansion of gambling a priority.

Opposition to casinos and expansion of casinos was believed to be especially strong in rural areas, like those found in McCoy’s beloved northeast Mississippi. It was many of those rural areas that were the homes to rural white Democrats — now all but extinct in the Legislature but at the time still a force in the House.

So, voting in favor of casino expansion had the potential of being costly for what was McCoy’s base of power: the rural white Democrats.

Couple that with the fact that the Democratic-controlled House had been at odds with the Republican Barbour on multiple issues ranging from education funding to health care since Barbour was inaugurated in January 2004.

Barbour set records for the number of special sessions called by the governor. Those special sessions often were called to try to force the Democratic-controlled House to pass legislation it killed during the regular session.

The September 2005 special session was Barbour’s fifth of the year. For context, current Gov. Tate Reeves has called four in his nearly six years as governor.

There was little reason to expect McCoy to do Barbour’s bidding and lead the effort in the Legislature to pass his most controversial proposal: expanding casino gambling.

But when Barbour ally Lt. Gov. Amy Tuck, who presided over the Senate, refused to take up the controversial bill, Barbour was forced to turn to McCoy.

The former governor wrote about the circumstances in an essay he penned on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina for Mississippi Today Ideas.

“The Senate leadership, all Republicans, did not want to go first in passing the onshore casino law,” Barbour wrote. “So, I had to ask Speaker McCoy to allow it to come to the House floor and pass. He realized he should put the Coast and the state’s interests first. He did so, and the bill passed 61-53, with McCoy voting no.

“I will always admire Speaker McCoy, often my nemesis, for his integrity in putting the state first.”

Incidentally, former Rep. Bill Miles of Fulton, also in northeast Mississippi, was tasked by McCoy with counting, not whipping votes, to see if there was enough support in the House to pass the proposal. Not soon before the key vote, Miles said years later, he went to McCoy and told him there were more than enough votes to pass the legislation so he was voting no and broached the idea of the speaker also voting no.

It is likely that McCoy would have voted for the bill if his vote was needed.

Despite his no vote, the Biloxi Sun Herald newspaper ran a large photo of McCoy and hailed the Rienzi worm farmer as a hero for the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a factual and balanced account of the political dynamics surrounding Hurricane Katrina recovery efforts in Mississippi, focusing on bipartisan cooperation between Democratic and Republican leaders. It highlights the complexities of legislative decisions without overtly favoring one party or ideology, reflecting a neutral and informative tone typical of centrist reporting.

Mississippi Today

PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership

NEW ALBANY — After five hours in a courtroom where attendees struggled to find standing room, the Mississippi Public Service Commission voted to petition a judge to put the Holly Springs Utility Department into a receivership.

The PSC held the hearing Thursday about a half hour drive west from Holly Springs in New Albany, known as “The Fair and Friendly City.” Throughout the proceedings, members of the PSC, its consultants and Holly Springs officials emphasized there was no precedent for what was going on.

The city of Holly Springs has provided electricity through a contract with the Tennessee Valley Authority since 1935. It serves about 12,000 customers, most of whom live outside the city limits. While current and past city officials say the utility’s issues are a result of financial negligence over many years, the service failures hit a boiling point during a 2023 ice storm where customers saw outages that lasted roughly two weeks as well as power surges that broke their appliances.

Those living in the service area say those issues still occur periodically, in addition to infrequent and inaccurate billing.

“I moved to Marshall County in 2020 as a place for retirement for my husband and I, and it’s been a nightmare for five years,” customer Monica Wright told the PSC at Thursday’s hearing. “We’ve replaced every electronic device we own, every appliance, our well pump and our septic pumps. It has financially broke us.

“We’re living on prayers and promises, and we need your help today.”

Another customer, Roscoe Sitgger of Michigan City, said he recently received a series of monthly bills between $500 and $600.

Following a scathing July report by Silverpoint Consulting that found Holly Springs is “incapable” of running the utility, the three-member PSC voted unanimously on Thursday to determine the city isn’t providing “reasonably adequate service” to its customers. That language comes from a 2024 state bill that gave the commission authority to investigate the utility.

The bill gives a pathway for temporarily removing the utility’s control from the city, allowing the PSC to petition a chancery judge to place the department into the hands of a third party. The PSC voted unanimously to do just that.

Thursday’s hearing gave the commission its first chance to direct official questions at Holly Springs representatives. Newly elected Mayor Charles Terry, utility General Manager Wayne Jones and City Attorney John Keith Perry fielded an array of criticism from the PSC. In his rebuttal, Perry suggested that any solution — whether a receivership or selling the utility — would take time to implement, and requested 24 months for the city to make incremental improvements. Audience members shouted, “No!” as Perry spoke.

“We are in a crisis now,” responded Northern District Public Service Commissioner Chris Brown. “To try to turn the corner in incremental steps is going to be almost impossible.”

It’s unclear how much it would cost to fix the department’s long list of ailments. In 2023, TVPPA — a nonprofit that represents TVA’s local partners — estimated Holly Springs needs over $10 million just to restore its rights-of-way, and as much as $15 million to fix its substations. The department owes another $10 million in debt to TVA as well as its contractors, Brown said.

“The city is holding back the growth of the county,” said Republican Sen. Neil Whaley of Potts Camp, who passionately criticized the Holly Springs officials sitting a few feet away. “You’ve got to do better, you’ve got to realize you’re holding these people hostage, and it’s not right and it’s not fair… They are being represented by people who do not care about them as long as the bill is paid.”

In determining next steps, Silverpoint Principal Stephanie Vavro told the PSC it may be hard to find someone willing to serve as receiver for the utility department, make significant investments and then hand the keys back to the city. The 2024 bill, Vavro said, doesn’t limit options to a receivership, and alternatives could include condemning the utility or finding a nearby utility to buy the service area.

Answering questions from Central District Public Service Commissioner De’Keither Stamps, Vavro said it’s unclear how much the department is worth, adding an engineer’s study would be needed to come up with a number.

Terry, who reminded the PSC he’s only been Holly Springs’ mayor for just over 60 days, said there’s no way the city can afford the repair costs on its own. The city’s median income is about $47,000, roughly $8,000 less than the state’s as a whole.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a factual and balanced account of the situation involving the Holly Springs Utility Department and the Mississippi Public Service Commission. It includes perspectives from various stakeholders, such as city officials, residents, and state commissioners, without showing clear favoritism or ideological slant. The focus is on the practical challenges and financial issues faced by the utility, reflecting a neutral stance aimed at informing readers rather than advocating a particular political viewpoint.

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

Portion of Gentilly Ridge Apartments residents return home, others remain displaced

-

Local News Video7 days ago

9/4 – Sam Lucey's “A Little More Humid” Thursday Night Forecast

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

Cruisin’ the Coast: Where Memory Meets the Open Road

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

3 states push to put the Ten Commandments back in school – banking on new guidance at the Supreme Court

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

Amid opposition to Blount County medical waste facility, a mysterious Facebook page weighs in

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

Reagan era credit pumps billions into North Carolina housing | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

Sickle Cell Disease Awareness Month