Mississippi Today

The death of rural hospitals could leave Mississippians ‘sick, sick, sick’

The death of rural hospitals could leave Mississippians ‘sick, sick, sick’

GREENWOOD – Only a few dozen cars sit in Greenwood Leflore Hospital’s parking lot.

The hospital’s windows, streaked with purple paint, read, “Stay strong!” Another one says, “We love our patients!” Behind the glass, magazines sit untouched on side tables —the lobby is vacant.

Greenwood Leflore is the community’s only hospital, and it’s months away from closing.

The COVID-19 pandemic drained the hospital, which was already financially vulnerable, dry. Costs went up, while profit did not. Doctors and nurses, burned out from the pandemic, left in droves. Now, the hospital is shutting down floor after floor, cutting costs to maintain operations.

Mississippians know this story.

Dozens of hospitals across the state, many the only in their communities, are struggling to stay open.

A report from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform puts a third of Mississippi’s rural hospitals at risk of closure, and half of those at risk of closure within the next few years. There are only three other states with worse prognoses.

But it’s especially devastating in Mississippi, where life expectancy and health outcomes are consistently the worst in the country.

Hospital administrators are holding their breath, waiting on help from the state, but they could be getting less money this year than they need. And there’s little to no chance that state leaders will expand Medicaid this year as 40 other states have done. Expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act would bring more than $1 billion in federal funding to Mississippi in a year.

Ryan Kelly, executive director of the Mississippi Rural Health Association, said the situation is dire, and there’s not a straightforward answer.

“I wish, for the sake of simplicity, I had one single thing I could point to and say this is the problem,” he said. “We have been saying this for a long time that this will get serious and it is now serious.

“We are in far more of a serious time now than we ever have been before.”

For the hospital CEOs, doctors and residents of rural Mississippi, this isn’t just a statistic. It’s a life-and-death reality.

‘Hospitals can close. Watch and see.’

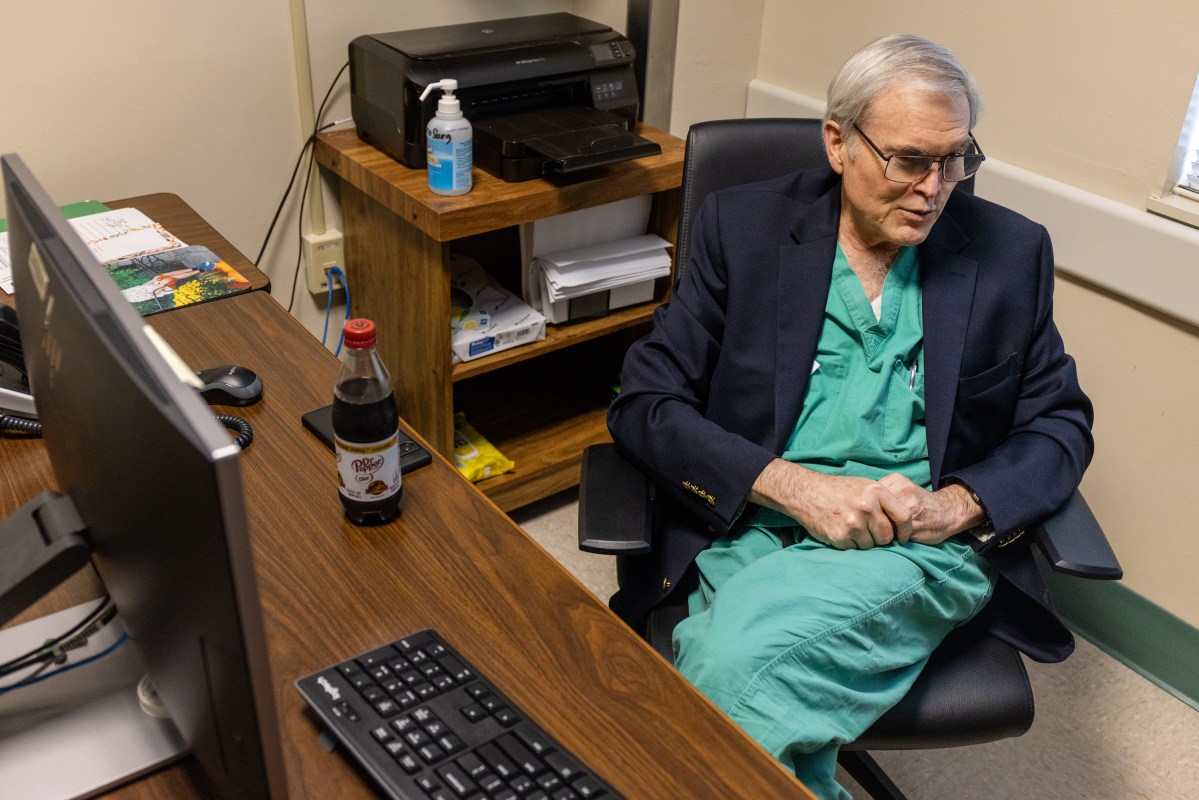

Dr. John Lucas’s office is at the end of a quiet hallway, past empty rooms with empty beds.

Though he’s spent his entire professional life at Greenwood Leflore, Lucas, a longtime Greenwood resident and now chief of staff, remembers starting his career as a surgeon in a much different hospital than the one he sees today.

His late father, Dr. John Lucas Jr., practiced at Greenwood Leflore from 1963 until his retirement in 2011. Back in the hospital’s heyday, Lucas said his father’s patients overflowed into the hallways. At that time, the hospital was licensed for 250 beds, he said.

When Lucas joined his father at the hospital in 1988, he didn’t experience that level of activity, but it was a far cry from the desolate hospital he serves today.

“It wasn’t uncommon to have as close to 200 beds full when I first came here,” he said. “It’s really sad to walk these empty halls and to see that we only have one part of one floor occupied with patients.”

In the past decade, Lucas has watched the hospital close unit after unit, tapering services in an effort to stay open.

First it was the neurosurgery department. Then, it was the urology department and inpatient dialysis. Now, the hospital doesn’t have full coverage of its emergency room for orthopedics or general surgery. Most recently, it shuttered its labor and delivery department and intensive care units.

At a health affairs committee meeting in February, Nelson Weichold, chief financial officer at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, said the worst part about the looming hospital closures is the slow cessation of services.

“It’s not just when the hospital closes,” he said. “It’s the years building up to that when they’re taking financial measures to do everything they can to try and keep the doors open.”

But it’s not financially viable to keep all of those service lines open anymore, according to Greenwood Leflore’s interim CEO Gary Marchand.

About 75% of the hospital’s patients are uninsured or on Medicaid or Medicare, which underpay the hospital for its services, Marchand said.

So most of the time, that means the hospital is losing money caring for its patients. And for the quarter of patients who have commercial insurance, the hospital often has to fight with the company to get the claim paid, he said.

“Our challenge is we have to map the inadequacy of those payments to our cost structure,” Marchand said. “For years, systemically, they (Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurance) have paid below real cost.”

Before 2020, the hospital was losing between $7 to $9 million a year, Marchand said. To satisfy the city and county, which partially own the hospital, Greenwood Leflore leaders came up with a plan to generate $7 million a year to break even.

Then COVID hit, and everything changed.

The hospital went into the pandemic with $20 million in cash reserves. With each wave of the virus, despite government relief, their reserves were depleted. By the end of 2021, half of the cash was gone.

It’s a fallacy that hospitals made money during the pandemic, Marchand said. Because Medicaid and Medicare paid for patients by their diagnosis, not the length of their hospital stay, patients who were in the ICU for weeks ended up costing the hospital.

Greenwood Leflore hasn’t been able to make the money back — it’s not clear why, but fewer people are seeking care, and payments have remained stagnant.

For several months, the University of Mississippi Medical Center was entertaining a plan to lease the hospital, saving it from closure. However, in November, the deal abruptly fell through without explanation from UMMC.

Marchand said the hospital has six months to figure out a plan or it’ll be forced to close.

“The struggle is to get the community and the legislators and others to understand a hospital is a business,” he said. “I think a lot of people think, ‘Oh, you need hospitals. They’re never going to go away.’

“Hospitals can close. Watch and see.”

A quick scroll on the hospital’s Facebook page shows that Greenwood residents know that closure is a real possibility.

Lucas said he hears the same refrain over and over again when he’s out in the community: “How’s the hospital doing?”

“Whenever I go to a social outing, it’s the first thing I get asked,” Lucas said. “Everybody’s concerned.”

Pie Fincher and her family are products of Greenwood Leflore Hospital.

Fincher, who is 89 years old, has only gone to another hospital for treatment one time in her life. Both of Fincher’s children were born at Greenwood Leflore, and the hospital has saved her life several times, she said, including once when she had a major brain bleed.

“It’s just been a lifeline for our family,” Fincher said.

But the neurology department doesn’t exist anymore. Neither does labor and delivery. Those doctors that delivered her kids and saved her life are long gone.

“I vividly remember how proud we were of that hospital to be built (in its current location in 1952),” Fincher said. “It was just state of the art everything. As time has gone on, we’ve been so fortunate to have so many wonderful doctors.

“That’s what’s so heartbreaking about it, is we have all these wonderful doctors that are willing to work in Greenwood — this little small, nondescript, tiny town — and we let them go.”

DeWitt Kimble was born in Greenwood 72 years ago. In the past few years, because of problems with his prostate, he’s increasingly relied on the hospital for emergency care.

Kimble first heard the hospital might shutter about a decade ago. Now that its closure is imminent, he’s worried.

“If you really close this hospital down, we’re going to have to go to Jackson,” he said. “We’re going to have to go to Grenada. We’re going to have to go to Cleveland, and a lot of people don’t have transportation, like me.”

The motor gave out on Kimble’s Suburban about a month ago, and he’s not been able to afford its repair.

If the hospital closes, residents such as Kimble will be forced to travel a half hour or more for care. In the Delta, where much of the population struggles with reliable transportation, the lack of a nearby hospital could be fatal.

Between a quarter and a third of Lucas’ surgeries are canceled, largely because of transportation issues, he said.

Kimble had a surgery scheduled on Monday to remove his catheter. His primary care physician at a private practice said he’d arrange for Kimble’s transportation, but Kimble said he’s called the office repeatedly, and no one has answered.

No one from his doctor’s office could be reached for comment by press time.

Kimble never made it to his procedure.

“I’m just sitting here, so frustrated,” he told Mississippi Today on Monday afternoon.

That means Kimble will still have to rely on his doctor in Greenwood and the hospital for continuing care.

“If the hospital closes, there will be a lot of walking dead,” he said. “Folks will be sick, sick, sick.”

Marchand’s Plan A is getting Greenwood Leflore designated as a critical access hospital. That means the hospital would have to give up almost all of its 200 beds, but it would get more money for services that it provides. Critical access hospitals are typically reimbursed by Medicare at a rate of 101%, theoretically allowing a 1% profit.

State Health Officer Dr. Dan Edney said closing service lines and applying for different hospital designations are solutions he’s seen increasingly across the state, but especially in the Delta. Though they might keep hospitals open, it’s still a loss for the community, he said.

“You take what was a vibrant hospital in the Delta, pre-pandemic, and now it’s a shell of its former self, post-pandemic,” Edney said. “Their only road to survivability is to downgrade.”

But to qualify for the designation, Greenwood Leflore would have to be 35 miles from the nearest hospital.

They’re just short —South Sunflower County Hospital in Indianola is 28 miles away.

Marchand is hoping for a waiver from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare regarding the distance requirement. His argument is that because of transportation challenges for the hospital’s population, the hospital should be an exception.

If that doesn’t work, the hospital will go up for sale again.

The survival of Delta’s largest health care system will be ‘touch and go’ after this year

If you ask Iris Stacker, interim CEO of Delta Health System in Greenville, how long the hospital system has before it’s forced to close, perplexingly, she smiles.

“I intend to be here forever,” Stacker says.

But Chief Nursing Officer Amy Walker raises an eyebrow.

“We’ll be here through the end of the year,” Walker deadpans. “It’s really touch and go after that.”

The duo head up the largest health care system in the Mississippi Delta. And together, they’re trying to keep it from closing.

Walker’s cynicism is often balanced out by Stacker’s cheeriness, but they do agree on one thing: The hospital is losing money.

“Even Positive Polly over there can’t deny that,” Walker said.

Despite being licensed for over 300 beds, the hospital’s census hovers around 80 patients. And most of the patients are uninsured or on Medicaid or Medicare.

Last year, Delta Health spent about $26 million on uncompensated care. That amounts to about 15% of its total operating expenses.

“We don’t turn people away,” Stacker said. “Instead of trying to go to a doctor and pay for that visit, they wait until 5 p.m. and come to our emergency room.”

But the decline in hospital patients isn’t because care isn’t needed in the Delta, which has some of the worst health disparities in Mississippi.

“It’s not because the patients aren’t here,” Walker said. “It’s because we don’t have the nurses to take care of them.”

Walker said the hospital has long struggled to recruit nurses to Mississippi, much less the Delta.

“We’ve always had that problem,” Walker said. “And if you look at our salaries, we usually have to pay more than Memphis and Jackson to get nurses here. We were already used to doing that.”

The problem worsened during the pandemic, as nurses were offered more money to travel or work elsewhere. Others got so burned out that they went ahead and retired. Statewide, nurse vacancies and turnover rates are at a 10-year high.

Since the pandemic, the hospital’s nurse workforce has nearly halved.

The exodus’ effects have rippled throughout the hospital: emergency wait time has quadrupled, the largest medical surgery unit is closed, and half of the hospital’s ICU beds are not in use.

“You would think that now three years out, things would have normalized, but they haven’t, and I don’t think we’re ever going to get back to normal,” Walker said. “We’ve lost so much of our volume at this point. I can’t really predict if it will come back.”

During the pandemic, supply and labor costs shot up. While prices aren’t as high as they were then, they haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The way Walker explains it, if the price of eggs goes up, a grocery store can make up for the inflation by passing the cost down to the consumer. But that can’t happen in a hospital setting.

Delta Health has to keep serving its patients, no matter if it’s losing money or not.

“We’re pretty much living on grant money right now,” Stacker said.

Stacker knows that Medicaid expansion is unlikely to pass this legislative session, though it’s what she thinks would help the most.

Without systemic changes, Stacker admits that the hospital’s fate is uncertain.

And if the Delta loses the hospital system, it’s going to affect the entire region.

“We save people’s lives every day here,” Walker said. “Once hospitals start closing, those patients aren’t just going to go away.”

Staying afloat, for now

Winston Medical Center’s CEO Paul Black is a numbers guy.

Black’s hesitant to say it, but he admits that his background has helped keep the hospital afloat.

Before taking the helm of the hospital, Black did consulting work for hospitals around the state and made use of his accounting degree as an auditor for the Medicare program.

“This reimbursement stuff is what I grew up doing,” he said. “So when I got started, I had already been on that side of the fence.”

Something his financial background did not prepare him for, though, was a disaster in his first week of work in April 2014.

Six days into his tenure, Louisville was hit by a devastating EF-4 tornado.

“I don’t remember a whole lot about what took place the first six months,” Black said. “I won’t say that I walked around in a fog, but there was just so much going on. And there’s no manual for it.”

During that time, funding was coming from various sources — disaster relief, cash reserves, community loans —which is why, years later, Black said the hospital’s finances don’t look as dire as many other hospitals in the state.

Winston lost money caring for patients during the pandemic, and Black said expenses have gone up while payments have not increased. The nursing home’s population has also been depleted because so many elderly Winston County residents died during the pandemic.

However, Black fought back with changes of his own.

The hospital raised nurse salaries, which convinced many to stay. Additionally, he’s made sure the hospital offers a diverse array of services —from a nursing home to mental health needs — to protect them from financial collapse.

“That keeps a lot of people coming here,” he said. “We’ve been very efficient with what we’re doing.”

But he warned that Winston Medical Center, while not in the red, isn’t in the green either.

Black’s predecessor, Lee McCall, now heads up Neshoba County General Hospital in Philadelphia, less than an hour from Louisville.

Neshoba County was similarly impacted by COVID —McCall said hospitalizations are down by about half, in part because many of the hospital’s chronically ill and elderly patients who regularly sought care or were in the nursing home died during the pandemic.

When McCall took the CEO job in 2014, the hospital averaged 1,500 annual admissions. Last year, they had 750.

Because of the drop in census, the hospital closed one of its acute floor wings in October to cut costs.

Additionally, more people are visiting the emergency room, where they know the hospital will provide care, whether or not they’re insured.

“Our ER visits have definitely gone up,” said Dr. Jon Boyles, the hospital’s emergency department director. “We’re seeing it seems more and more people who basically use the ER as a clinic.”

The hospital also lost staff during the pandemic — staff they can’t afford to hire back. McCall said he’s trying to do everything he can to prevent layoffs.

“To be honest, there’s just not anywhere to really lay off unless we just shut down a service line completely, which we’re trying to avoid at all costs,” he said.

McCall has kept a close eye on the Capitol the past few months. Like Stacker in Greenville, McCall knows Medicaid expansion isn’t going to happen this session, but he’ll keep advocating for it.

He doesn’t deny that hospitals need the grant money making its way through the Legislature, but said hospitals need a sustainable solution — not a temporary one.

“That’s one-time money,” McCall said. “That doesn’t fix the ongoing problem. So we’re going to be right back where we are now next year.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling.

A Jackson County Chancery Court judge is denying the public access to a case that involves several politically connected Mississippians and their failed venture to ticket uninsured motorists using cameras and artificial intelligence.

Media companies Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald have filed for relief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Chancery Judge Neil Harris improperly closed the court file without notice and a hearing to consider alternatives. The media outlets say the court file should be opened.

Mississippi Today in June filed its motion asking that Harris unseal the case, which he denied six days later.

Gulfport attorney Henry Laird writes in the media companies’ petition for state Supreme Court review, “The Chancery Court sealing the entire court file both before and after Mississippi Today’s motion to unseal the file violates the public and press’ cherished right of openness and access to its public court system and records.”

Mississippi judges have long followed a 1990 state Supreme Court decision that says, “A hearing must be held in which the press is allowed to intervene on behalf of the public and present argument, if any, against closure.”

Instead, Harris said he found no hearing necessary after reviewing the pleadings to open the file. The case, he said, is between two private companies.

“There are no public entities included as parties,” he wrote, “and there are no public funds at issue. Other than curiosity regarding issues between private parties, there is no public interest involved.”

The case involves what is usually a public function: Issuing tickets to the owners of uninsured vehicles. And, according to one party to the case, the Mississippi Department of Public Safety is owed $345,000 from the uninsured motorist program.

READ MORE: Private business ticketed uninsured Mississippi vehicle owners. Then the program blew up.

Since the entire court file is closed, the public is unable to see why the judge sealed the case. The Mississippians said in the Chancery Court case that they have “substantial” business interests to protect and “a lot of political importance,” an attorney opposing them said in a related federal case that is not sealed.

Georgia-based Securix LLC signed up its first Mississippi client in 2021, the city of Ocean Springs, an agreement with the city showed. Securix developed a program that uses traffic cameras, artificial intelligence and bulk data on insured motorists to identify the owners of vehicles without insurance.

To sign on other Mississippi cities, Securix enlisted three well-known consultants, Quinton Dickerson, Josh Gregory and Robert Wilkinson. Dickerson and Gregory are Republican political operatives in Jackson who have run numerous state and local campaigns and advise many of the state’s top elected officials. Wilkinson, a Coast attorney, has represented local governments and government agencies, including the city of Ocean Springs.

MS business partnership sours

In 2023, the Mississippians formed QJR LLC. Their company entered a 50-50 partnership with Securix called Securix Mississippi.

Securix Mississippi sold the cities of Biloxi, Pearl and Senatobia on the uninsured driver program.

Fees collected from uninsured drivers were apportioned to the company, the cities and the Department of Public Safety, the operating agreement with Biloxi showed.

The citations offered three options, according to copies included in a federal lawsuit filed by three Mississippi residents who received them:

- Call a toll-free number and provide proof of insurance.

- Enter a diversion program that charges a $300 fee and includes a short online course and requires agreement that the vehicle will not be driven uninsured on public roadways.

- Contest the ticket in court and risk $510 in fines and fees, plus the potential of a one-year driver’s license suspension.

The Securix Mississippi partnership soon soured.

Securix Chairman Jonathan Miller of Georgia said in a sworn court declaration submitted in the federal case that he was subjected around March 2024 to a “freeze out” by members and/or employees of QJR. They stopped giving him information, Miller said.

The Department of Public Safety in August pulled the plug on the controversial ticketing program, shutting off the company’s access to the insured driver database.

In September, QJR filed its Chancery Court lawsuit against Securix LLC.

What is known about the case comes from documents in the federal court file. QJR claims the company and its members have been defamed by Miller and Securix and wants their 50-50 business partnership dissolved.

The Chancery Court case does not even show up when the parties are searched for by name.

With a case number gleaned from the federal court file, a search of chancery records shows only that the case is under seal.

Normally, when a case is under seal, the docket would still be available. A docket lists all records and proceedings in a case. While sealed records are listed and described, they can’t be viewed.

“There is no court file,” attorney Laird said in asking the Supreme Court to review Judge Harris’ decision to leave the file sealed. “There is no docket sheet. There is absolutely no access on the part of the public or press to their public court file in this case.”

Judge closes file without public notice

All Mississippi court files are presumed open unless they are closed with notice and a hearing under guidelines established in the 1990 case Gannett River States Publishing Co. vs. Hand.

“It appears that the judge ignored what has been settled law in Mississippi since 1990,” said retired Jackson attorney Leonard Van Slyke, who represented Gannett in the case and still advises the media.

He added, “Since that time, there have not been many efforts to close a courtroom or a court file because the rules are pretty clear as to when that can be done. It is obvious from the rules that this would be a rare occurrence.”

A court file can be closed only if a party in the case requesting closure can show an “overriding interest” that would be prejudiced by publicity.

The Supreme Court said in 1990 that the public is entitled to at least 24 hours’ notice — on the court docket — before a judge considers closure. As a representative of the public, the media has a right to a hearing before a court file or proceeding is closed.

At the hearing, the judge must consider the least restrictive closure possible and reasonable alternatives. The judge also must make findings that explain why alternatives to closure were rejected.

The court wrote in Gannett vs. Hand:

“A transcript of the closure hearing should be made public and if a petition for extraordinary relief concerning a closure order is filed in this Court, it should be accompanied by the transcript, the court’s findings of fact and conclusions of law, and the evidence adduced at the hearing upon which the judge bases the findings and conclusions.”

Because Judge Harris held no hearing, the high court will have a scant record on which to base its review. Without a court record, Laird pointed out in his filing, the public can have no confidence the judge made a sound decision.

Kevin Goldberg, an attorney who serves as vice president and First Amendment expert at the nonpartisan, nonprofit Freedom Forum, said the First Amendment guarantees the public access to courts.

In the Securix case, he said, a private business was doing work normally performed by a police department or other public agency, and residents could be snared into legal proceedings when they received tickets and public funds were involved.

“These are not private people in a small town, going about their business,” Goldberg said. “These people’s business is the public’s business . . . I think that means they need to accept that they’re going to be scrutinized all the time, including when they voluntarily make a decision to go to court.”

This article was produced in partnership between the Sun Herald and Mississippi Today.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling. appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article maintains a largely factual and investigative tone, focusing on government transparency, judicial procedure, and public access to court records. It critiques the secrecy upheld by a judge in a politically sensitive case involving private companies executing public functions, highlighting concerns about accountability and public interest. The framing leans slightly toward advocating for open government and media rights, values often associated with center-left perspectives. However, it stops short of overt ideological framing or partisan language, striving to report the facts and legal context while underscoring the public’s right to scrutiny.

Mississippi Today

Why Andy Gipson is running for governor

Republican Andy Gipson, the first candidate to publicly announce a run for Mississippi governor in 2027, outlines his five-plank platform. No. 1 is fighting crime, which Gipson says is rising in what were once quiet rural areas, because “If people don’t feel safe, nothing else matters.” He also offers a brief sampling of his baritone crooning from his just-released two studio albums.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Why Andy Gipson is running for governor appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Mississippi Today

‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious

Superintendent Errick Greene wanted to be very clear with the roughly 50 parents who attended Thursday night’s community listening session: Jackson Public Schools already has a policy banning students from using cellphones at school.

But the leadership of Mississippi’s third-largest school district has decided that a new approach is in order, citing a series of incidents in recent years involving students using their cellphones to bully others, organize fights or text their parents inaccurate information about violence happening at or near their school.

“To be clear, it’s not the majority of our scholars, but I can’t look at a class and know who’s gonna be bullying today, who’s gonna be scheduling a meetup to cut up today,” Greene said toward the end of the hour-long meeting held at the JPS board room. “I can’t look at a group of scholars and say, ‘OK, yeah, you’re the one, let me take your phone, the rest of you can keep it.’”

Under the rewritten policy, students who take their phone out of their backpacks during the instructional day will lose it for five days for the first infraction, 10 days for the second and 45 days for the third. Currently, the longest the school will hold a phone is 10 days.

The Jackson school board is expected to consider the new policy at its meeting next week and the district hopes to implement the change when the new school year starts later this month, said Sherwin Johnson, the district’s communications director.

Students also currently have the option to pay up to a $25 fine to get their phone back, but the district wants to rescind that aspect of the policy.

“We’ve discovered that’s not equitable,” said Larrisa Harris, the JPS general counsel. “Not everybody has the resources to come and pay the fine.”

Support for the new policy among the parents who spoke at the listening session varied, but all had questions. How will students access the internet on their laptops if the WiFi is spotty at their school and they need to use their cellphone hotspot? If students are required to keep their phones in their backpacks during lunch, how will teachers prevent stealing? How will JPS enforce the ban on using cellphones on the bus?

One mother said she watches her daughter’s location while she rides the bus to Jim Hill High School so she knows her daughter made it safely.

“If they can’t have it on the bus, who’s gonna enforce that?” she said. “I’m just gonna be real, the bus driver got to drive.”

A common theme among parents was anxiety at the prospect of losing direct contact with their kids in the event of an emergency. A Pew Research survey found that most adults, regardless of political affiliation, support cellphone bans in middle and high school classes. But those who don’t say it’s because their child can use their phone during emergencies.

“If something happened, will we get an automatic alert to notify us? Because a lot of the time we see things on social media first,” said Ashley McIntyre, a mother of three JPS students. She attended the meeting with her eldest daughter, Aaliyah, who recently graduated from Powell Middle School.

Though JPS does have an alert system for parents, McIntyre said she didn’t know if it existed. She cited a bomb threat at Powell last year that she found out about because Aaliyah texted her, not through a school alert.

“We didn’t know what was going on, and she texted me, ‘Mom, I’m scared,’ so I went up there,” McIntyre said. “So that puts us on edge.”

Aaliyah said she uses her phone to text her mom and watch TikTok, but she feels like her classmates use their phones to be popular or to fit in. When a fight happens, she said many students pull out their phones to record instead of trying to get an adult who can stop it. Then the videos end up on Instagram pages dedicated to posting fights in JPS.

“Once the principal found out about the fight pages, they came around looking inside our videos and camera rolls,” she said. “It happened to me last year. They thought I had a fight on my phone.”

Toward the end of the meeting, Laketia Marshall-Thomas, the assistant superintendent for high schools, took the mic to respond to one parent who said she was concerned that older students would not come to school if they knew their phone could be taken.

“What we have seen is, it’s the older students—” Marshall-Thomas began.

“They are the problem,” someone from the audience chimed in.

“We’re not saying they cannot have them,” she continued. “We know that they have after school activities and they need to communicate with their moms … but we have had major, major issues with cellphones and issues that have even resulted in criminal outcomes for our scholars, but most importantly, our students … have experienced a lot of learning loss.”

While the district leadership did not go into detail about the criminal incidents, several pointed to instances where students have texted their parents inaccurate information, such as an unsubstantiated rumor there was a gun during a fight at Callaway High School or that a shooting outside Whitten Middle School occurred on school property.

“Having phones actually creates far more chaos than they help anyone,” Greene said.

While cellphones have been banned to varying degrees in U.S. schools for decades, youth mental health concerns have renewed interest in more widespread bans across the country. Cellphone and social media usage among school-aged kids is linked to negative mental health outcomes and instances of cyberbullying, research shows.

At least 11 states restrict or ban cellphone use in schools. After Mississippi’s youth mental health task force recommended that all school districts implement policies that limited cellphone and social media usage in classrooms, a bill that would’ve required school boards to create cellphone policies died during the legislative session. Still, several Mississippi school districts have passed their own policies, including Marshall County and Madison County.

Another concern about the ban was a belief among a couple of speakers at the meeting that cellphones can help parents hold the district accountable for misdeeds it may want to hide.

“I just saw a video today. It was not in JPS, but it was a child being yelled at by the teacher and had he not recorded it, his momma would have never known that this sweet lady that they go to church with is degrading her child like that,” one mother said.

Statements like these prompted responses from teachers and other parents who urged the skeptical attendees to be more trusting or to make sure the district has updated contact information for them in case school officials need to reach parents during an emergency.

“I think we have to trust the people watching over our children,” said one of the few fathers who spoke. “When I grew up, what the teacher said was gold.”

One teacher asked the audience, “Will you trust us?”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post ‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a balanced report on Jackson Public Schools’ proposed stricter cellphone policy without taking a clear ideological stance. It fairly conveys the perspectives of school officials emphasizing discipline and safety, alongside parental concerns about communication and emergency access. The tone remains neutral, focusing on factual details such as policy changes, reasons behind them, and community reactions. While it includes some skepticism from parents and responses from district staff, the language does not endorse or oppose either side. Overall, the coverage adheres to neutral, factual reporting by presenting multiple viewpoints without editorializing.

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Learning loss after Helene in Western NC school districts

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed1 day ago

Bread sold at Walmart, Kroger stores in TN, KY recalled over undeclared tree nut

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Turns out, Medicaid was for us

-

Local News7 days ago

“Gulfport Rising” vision introduced to Gulfport School District which includes plan for on-site Football Field!

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed6 days ago

The Bayeux Tapestry will be displayed in the UK for the first time in nearly 1,000 years

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Arkansas Department of Education creates searchable child care provider database

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

With brand new members, Louisiana board votes to oust local lead public defenders

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts