Mississippi Today

New Evidence Raises Questions in Controversial Mississippi Law Enforcement Killing

When Damien Cameron’s body arrived at the Mississippi State Medical Examiner’s Office in August 2021, it bore all the signs of a police brutality case.

Mr. Cameron’s face was bloody and swollen almost beyond recognition from his struggle with Rankin County sheriff’s deputies the week before.

Signs of internal bleeding on the side of the neck of Mr. Cameron, a 29-year-old Black man, suggested a deputy might have pinned him to the ground with a knee — a dangerous restraint technique condemned by the Justice Department and banned in many cities.

But when the state’s chief medical examiner, Dr. Staci Turner, completed her autopsy, she ruled the cause of Mr. Cameron’s death “undetermined.” A grand jury later declined to indict the deputies involved.

Now, three renowned pathologists, who examined the case at the request of The New York Times and Mississippi Today, say Mr. Cameron’s death should have been ruled a homicide.

After independently reviewing autopsy photos, sheriff’s reports, hospital records and eyewitness statements saying two deputies knelt on Mr. Cameron’s neck for 10 minutes or more, the experts concluded the deputies most likely killed him.

His death was “a homicide, absolutely,” said Dr. Michael Baden, a former New York City chief medical examiner who testified in the O.J. Simpson trial and performed an independent autopsy of George Floyd. “This person died of asphyxia because of neck compression.”

“There’s really nothing to be undetermined about,” said Dr. Zhongxue Hua, chief of the forensic pathology division at Rutgers University.

The opinions of these forensic experts give new ammunition to Mr. Cameron’s family, who have struggled to bring attention to his death for more than two years. Despite local media coverage and two ?articles by the news site Insider, Mr. Cameron’s death never surfaced nationally like the cases of George Floyd or Eric Garner.

Mr. Cameron’s mother, Monica Lee, described her son as an outgoing young man who could quickly turn strangers into friends with his smile. Ms. Lee has always maintained that the deputies killed her son by violently subduing him and ignoring his cries that he could not breathe. She predicted the investigation into his death “was going to be a bunch of lies.”

Ms. Lee sued the department in 2022.

Her lawyer, Malik Shabazz, said the conclusions of the independent pathologists could change the outcome of Ms. Lee’s case. “There’s serious questions about the competency and the accuracy of the autopsy findings,” he said.

Mr. Cameron is one of at least nine men who have died during episodes involving Rankin deputies since 2014, according to department records and Mississippi Bureau of Investigation reports.

Rankin County, a rural, majority-white community outside Jackson, has been rocked by national controversy this year after five sheriff’s deputies and a local police officer broke into the home of two Black men, tortured them for two hours, sexually assaulted them with a sex toy and then shot one of them in the mouth.

On Aug. 3, Deputy Hunter Elward admitted to sticking his gun in 32-year-old Michael Jenkins’s mouth and firing it. He and the other officers, who are all white, concealed their crimes by planting a gun and drugs on their victims, disposing of security camera footage and falsifying sheriff’s reports, according to an investigation by the Justice Department. All of the officers pleaded guilty to federal and state charges in the case.

“Obviously these officers can’t be trusted,” said Sean Tindell, commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Public Safety. “There’s probably going to be a lot of reviews of every case that they’ve ever worked on.”

Mr. Elward was one of the two deputies accused of kneeling on Mr. Cameron the day he died.

A violent arrest

The only witnesses to Mr. Cameron’s arrest on July 26, 2021, were the deputies, Ms. Lee and her parents.

That afternoon, a neighbor called the police to report a burglary he believed Mr. Cameron had committed at his home in a quiet, rural neighborhood near Braxton, Miss., court records show.

When Deputy Elward arrived to investigate, Mr. Cameron, who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, swung at him and ran away, according to the sheriff’s report.

Deputy Elward fired his Taser and tackled Mr. Cameron, he claimed in his sheriff’s report, punching him three times in the face before Deputy Luke Stickman arrived to help subdue and arrest the man.

Mr. Cameron continued to resist the deputies as they led him outside and shoved him in a patrol car, Deputy Elward contended in his report.

Shortly after, he found Mr. Cameron unresponsive. Paramedics took him to University of Mississippi Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead.

Mr. Cameron’s family said they witnessed a drastically different encounter.

In interviews with reporters, Ms. Lee said her son never tried to hit the deputy.

Hours after the incident, Mr. Cameron’s grandfather told Mississippi Bureau of Investigation agents that he had witnessed a deputy placing his knee on his grandson’s neck as he lay on the ground. The deputies did not mention kneeling on Mr. Cameron in their reports.

Ms. Lee told reporters that Deputies Elward and Stickman knelt on Mr. Cameron’s neck and back for at least 10 minutes.

“He was telling me he couldn’t breathe, he couldn’t breathe,” she said.

Mr. Cameron’s mother told reporters that he struggled to walk as the deputies took him to the patrol car and that he fell facedown in the mud in front of it.

There is no video footage of the incident.

In a written statement, Sheriff Bryan Bailey said the department had yet to deploy body-worn cameras when Mr. Cameron was arrested. Mississippi does not require law enforcement agencies to use them.

Without footage to prove her claims, Ms. Lee hoped her son’s autopsy would finally reveal the truth about his death.

But after the medical examiner’s report came back “undetermined,” the Rankin County District Attorney’s Office declined to charge the deputies. District Attorney John Bramlett, known as Bubba, did not return calls seeking comment about why he did not pursue charges.

“It was heartbreaking,” Ms. Lee said. “This is what you do every day, and you could not determine his cause of death? Why?”

Medical examiners’ findings serve as the legal foundation for prosecutors to file charges against officers involved in fatal incidents, legal experts said.

“The only person in a homicide case who can testify to the ultimate issue — that the manner of death was homicide — is a medical examiner,” said Aramis Ayala, a former Florida state attorney and a professor at Florida A&M University School of Law.

Prosecutors rarely pursue homicide charges against police officers. Without an official cause of death, experts said the chances of persuading a grand jury to indict an officer ?were slim.

A death unexplained

Dr. Turner declined to discuss the details of Mr. Cameron’s autopsy, but said there was nothing unusual about her decision not to cite a cause of death.

In cases where her office is missing information or can’t definitively cite a cause, “we err on the side of ‘undetermined’ because we don’t want to make a mistake,” she said.

Dr. Turner would not comment on what police documents and witness statements she had access to when she performed the autopsy. But in her report she wrote, “Due to lack of access to information involving the circumstance of this death, the cause and manner of death are best classified as undetermined.”

All three independent forensic pathologists said the medical examiner should have tracked down (gotten) the information she needed to make a determination. The hemorrhaging in Mr. Cameron’s neck made it clear he died of asphyxiation, they said.

“They should not have signed it on as undetermined and let it go,” said Dr. Cyril Wecht, former president of the American College of Legal Medicine and the American Academy of Forensic Science. “That was up to them to get more information from the cops.”

A toxicology report found methamphetamine in Mr. Cameron’s blood, but the pathologists? ? agreed that the drug did not cause his death.

Representatives of the medical examiner’s office said the agency would review the case again if asked by the Mississippi attorney general or the local district attorney’s office.

“It was undetermined,” said Mr. Tindell, the public safety department commissioner. “That doesn’t mean it can’t be determined later.”

In a written response to The Times, Sheriff Bailey said his department cooperated with the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation’s inquiry, noting that the bureau found no wrongdoing.

“If requested, we will fully cooperate with any future investigation into this incident by any investigative agency,” Sheriff Bailey wrote.

Mr. Shabazz said he planned to consult with the pathologists and update Ms. Lee’s lawsuit to include their findings. He hopes the new information will prompt state officials to review the case again.

Ms. Lee said she just wants the world to know the truth.

“This is what they did to my child,” she said. “You can’t tell me it was undetermined.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Indicted Jackson prosecutor’s latest campaign finance report rife with errors

Tangled finances, thousands in personal loans and a political contribution from a supposed investor group made up of undercover FBI informants — this was all contained in a months-late campaign finance report from Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens.

Owens, a second-term Democrat in Mississippi’s capital city region, is fighting federal bribery charges, to which he’s pleaded not guilty. At the same time, his recent campaign finance disclosure reflects a pair of transactions that correspond with key details in the government’s allegation that Owens took money from undercover informants to pay off a local official’s debt.

Regarding payments from Facility Solutions Team — the company name used in the FBI sting — to former Jackson City Councilwoman Angelique Lee, Owens allegedly stated the need to “clean it out,” according to the indictment, which was unsealed in November.

“[L]ike we always do, we’ll put it in a campaign account, or directly wire it,” he said, the indictment claims. “[T]hat’s the only way I want the paper trail to look.”

Agents recorded hundreds of hours of conversations with Owens and other officials, and after his arraignment last year, Owens responded to the charges, saying, “The cherry-picked statements of drunken locker room banter is not a crime.”

Throughout 2024, a non-election year during which federal authorities allege Owens funneled thousands of dollars in bribes to Jackson’s city officials, Owens loaned his campaign more than $20,000, according to his campaign committee’s finance report. He’d won reelection in late 2023.

Owens and his attorneys did not respond to questions about his campaign finance report.

Owens’ report, filed May 30 – months late and riddled with errors – is the latest example of how Mississippi politicians can ignore the state’s campaign finance transparency laws while avoiding meaningful consequences. It’s a lax legal environment that has led to late and illegible reports, untraceable out-of-state money that defied contribution limits, and, according to federal authorities, public corruption with campaign finance accounts serving as piggy banks.

Enforcement duties are divided among many government bodies, including the Mississippi Ethics Commission. The commission’s executive director, Tom Hood, has long complained that the state’s campaign finance laws are confusing and ineffective.

“It’s just a mess,” Hood said.

Owens filed the annual report months past the Jan. 31 deadline, after reporting from The Marshall Project – Jackson revealed he had failed to do so. He paid a $500 fine in April.

He was also late filing in previous years, paying fines in some years and failing to pay the penalties in other years, according to records provided by the Ethics Commission.

The report, which Owens signed, is full of omissions or miscalculations, with no way to tell which is which. The cover sheet of the report provides the total amount of itemized contributions and disbursements for the year — $44,000 in and $36,500 out. But the body of the report lists the line-by-line itemizations for each, and when the Marshall Project – Jackson and Mississippi Today summed the individual itemizations, the totals didn’t match those on the cover sheet.

Based on the itemized spending detailed in the body of the report, Owens’ campaign should have thousands more in cash on hand than reported. In the report’s cover sheet, Owens also reported that he received more in itemized contributions during the year than he received in total contributions, which would be impossible to do.

While the secretary of state receives and maintains campaign finance reports, it has no obligation to review the reports and no authority to investigate their accuracy. Under state law, willfully filing a false campaign finance report is a misdemeanor. Charges, however, are rare.

Owens is the only local official in the federal bribery probe — which is set to go to trial next summer — who remains in office. The government alleged that Owens accepted $125,000 to split between him and two associates in late 2023 from a group of men he believed were vying for a development project in downtown Jackson. Owens accepted several thousand dollars more to funnel to public officials for their support of the project, the indictment alleges. The use of campaign accounts was an important feature of the alleged scheme, according to the indictment.

Owens divvied up $50,000 from Facility Solutions Team, or FST, into checks from various individuals or companies — allegedly meant to conceal the bribe — to former Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba’s reelection campaign, the indictment charged.

Lumumba accepted the checks during a sunset cruise on a yacht in South Florida, the indictment alleged. His campaign finance report, filed earlier this year, reflected five $10,000 contributions near the date of the trip, with no mention of FST.

Lumumba, who lost reelection in April, has pleaded not guilty.

While the indictment accused Owens of saying that public officials use campaign accounts to finance their personal lives, state law prohibits the use of political contributions for personal use.

The indictment alleges Owens accepted $60,000 — some for the purpose of funneling to local politicians — from the men representing themselves as FST in the backroom of Owens’ cigar bar on Feb. 13, 2024. On his campaign finance report, he listed a $12,500 campaign contribution from FST two days later, the same day the indictment alleges he paid off $10,000 of former Councilwoman Lee’s campaign debt. Lee pleaded guilty to charges related to the alleged bribery scheme in 2024.

Also on Feb. 15, 2024, the campaign finance report Owens filed shows a $10,000 payment to 1Vision, a printing company that used to go by the name A2Z Printing, for the purpose of “debt retirement.” Lee had her city paycheck garnished starting in 2023 to pay off debts to A2Z Printing, according to media reports. No mention of Lee was made in the campaign finance report filed by Owens. The printing company did not respond to requests for comment.

Campaigns are allowed to contribute money to other campaigns or political action committees. If Owens’ committee used campaign funds to pay off debt owed by Lee’s campaign, the transaction should have been structured as a contribution to Lee’s campaign and reported as such by both campaigns, said Sam Begley, a Jackson-based attorney and election law expert who has advised candidates about their financial disclosures.

The alleged debt payoff on behalf of Lee is not the first time Owens has described transactions on his campaign finance filings in ways that may obscure how his campaign is spending money. Confusing or unclear descriptions of spending activity are common on campaign finance reports across the state.

Owens previously reported that in 2023, he paid $1,275 to a staff member in the district attorney’s office who also worked on his campaign. The payment was labeled a reimbursement, which Owens explained in a May email to The Marshall Project – Jackson was for expenditures this person made on behalf of the campaign, “such as meals for volunteers/workers, evening/weekend canvassers, and election day workers.”

State law requires campaigns to itemize all contributions and expenses over $200. Begley said he believes Owens’ committee should have itemized any payments over $200 made by anyone on behalf of the campaign.

Upfront payments, with the expectation of repayment by the campaign, might also be considered a loan, according to a spokesperson for the secretary of state. Campaigns are barred from spending money to repay undocumented loans.

The state Ethics Commission has addressed undocumented loan repayments in several opinions, outlining the required documentation to make repayments legal.

Since 2018, the Ethics Commission has had the power to issue advisory opinions upon request to help candidates and campaigns sort through laws that Hood, the commission’s executive director, said aren’t always clear.

The commission has issued just six opinions in seven years.

“I was surprised in the first few years that there weren’t more,” Hood said. “But now it seems to be clear that for whatever reason, most people don’t think they need advice.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Indicted Jackson prosecutor's latest campaign finance report rife with errors appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article critically examines the conduct of Hinds County District Attorney Jody Owens, a Democrat, and highlights systemic weaknesses in Mississippi’s campaign finance laws. While the reporting is grounded in factual evidence, legal documents, and expert commentary, the tone leans toward exposing flaws in enforcement and transparency—issues typically emphasized by center-left or reform-oriented journalism. The article does not display partisan rhetoric or ideological framing beyond its focus on accountability and legal integrity. Its publication by Mississippi Today and The Marshall Project, both known for investigative work with slight progressive leanings, further supports a Center-Left classification.

Mississippi Today

Whooping cough cases increase in Mississippi

The Mississippi State Department of Health issued an alert Wednesday that cases of pertussis, or whooping cough, are climbing in the state.

The year-to-date number of cases in Mississippi ballooned to 80 as of July 10. That compares to 49 cases in all of 2024.

No whooping cough deaths have been reported. Ten people have been hospitalized related to whooping cough, seven of whom were children under 2 years old.

Cases have largely been clustered in northeast Mississippi. The region accounts for 40% of cases statewide.

The nation has also seen rising rates of whooping cough, though cases have been climbing less steeply than in Mississippi. About 15,000 whooping cough cases have been reported nationwide this year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highly contagious respiratory illness is named for the “whooping” sound people make when gasping for air after a coughing fit. It may begin like a common cold but can last for weeks or months. Babies younger than 1 year are at greatest risk for getting whooping cough, and can have severe complications that often require hospitalization.

Whooping cough cases fell in Mississippi after the COVID-19 pandemic began, but have since rebounded. This is likely due to people now taking fewer mitigation measures, like masking and remote learning, State Epidemiologist Renia Dotson said at the state Board of Health meeting July 9.

The majority of cases – 76% – have occurred in children. Of the 73 cases reported in people who were old enough to be vaccinated, 28 were unvaccinated. Of those 28 people, 23 were children.

“Vaccines are the best defense against vaccine preventable diseases,” State Health Officer Dr. Dan Edney said after the State Board of Health meeting.

Mississippi has long had the highest child vaccination rates in the country. But the state’s kindergarten vaccination rates have dropped since a federal judge ruled in 2023 that parents can opt out of vaccinating their children for school on account of religious beliefs.

The pertussis vaccination is administered in a five-dose series for children under 7 and booster doses for older children and adults. The health department recommends that pregnant women, grandparents and family or friends that may come in close contact with an infant should get booster shots to ensure they do not pass the illness to children, particularly those too young to be vaccinated.

Immunity from pertussis vaccination wanes over time, and there is not a routine recommendation for boosters.

State health officials also encourage vaccination against other childhood illnesses, like measles. While Mississippi has not reported any measles cases, Texas has had recent outbreaks.

The Mississippi Health Department offers vaccinations to children and uninsured adults at county health departments.

Correction 7/16/25: This story has been updated to reflect that the age of the seven hospitalized children is under 2 years old.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Whooping cough cases increase in Mississippi appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a straightforward, fact-based account of rising whooping cough cases in Mississippi without ideological framing. It cites official sources such as the Mississippi State Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, offering context, statistics, and public health recommendations. While it mentions a 2023 federal court ruling that allowed religious exemptions to vaccinations—a potentially contentious topic—it does so factually without editorializing or assigning blame. The overall tone remains neutral and informative, aligning with public health reporting rather than political advocacy.

Mississippi Today

Driver’s license office moves to downtown Jackson

The driver’s license office in Jackson has moved downtown as the Mississippi Department of Public Safety prepares to shift its headquarters from the capital city to suburban Rankin County.

The department last month announced it was closing the license office that had operated for decades next to its headquarters just off Interstate 55 at Woodrow Wilson Avenue, near the VA Medical Center.

The new office is at 430 State St., near Jackson’s main post office and a few blocks from the Capitol.

“This location provides easier access for those who live and work in the area and ensures we can continue offering vital driver services in a more convenient and accessible space within the city of Jackson,” said Bailey Martin, spokesperson for the Department of Public Safety.

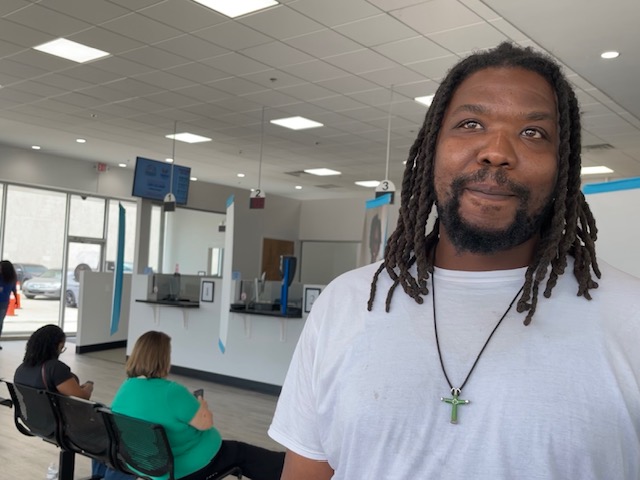

Mississippi has 35 driver’s licenses offices. The new Jackson office is in a former car dealership – an all-white building with floor-to-ceiling windows that fill the space with sunlight. On Wednesday, customers sat on black benches, chatting or scrolling on their phones while waiting to be called up to get or renew a license.

Carlos Lakes, 34, from Yazoo City, said he first went to the Richland office that issues commercial driver’s licenses but couldn’t get what he needed there. He said he then went to the old office on Woodrow Wilson and saw a note on the door showing the office had moved.

“So, it’s been about two hours of running around,” said Lakes, a truck driver.

He said the customer service at the new office was good, aside from the long wait time.

Medical student Seth Holton, 22, had a similar experience. He drove in from Flora, in Madison County, and went to the Woodrow Wilson location before finding the new office. He said it was his first time getting his license renewed.

“I think it looks nice,” Holton said of the new location. “I think it’s organized. There’s good seating. It’s pretty quick, for the most part.”

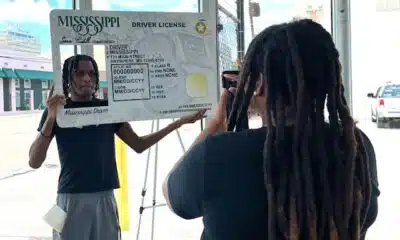

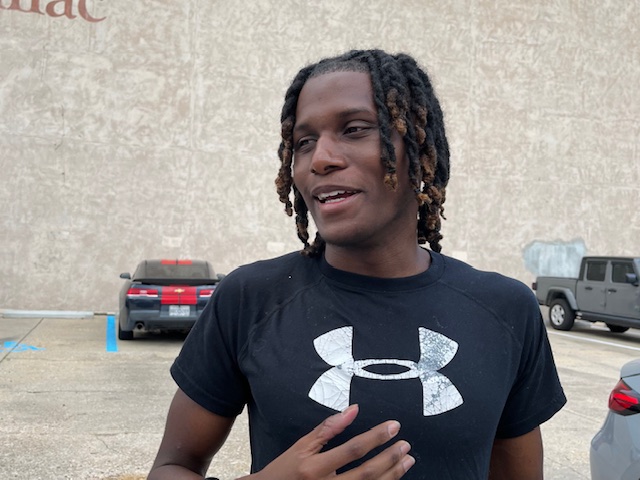

Student Marquerion Brown, 19, posed for photos with a large cardboard frame of a driver’s license in the corner of the new office. He’d just passed his driver’s test for the first time.

“I’m just lucky and thankful to get this one this time,” Brown said. He hadn’t decided where he wanted to drive first. “I got a lot of places in mind.”

The Department of Public Safety headquarters will open in Pearl within the next year, near the state’s crime lab, fire academy and emergency management agency.

Martin said the new headquarters will allow the department to have its divisions in one place – the highway patrol, bureau of investigation, bureau of narcotics, homeland security office and commercial transportation enforcement.

“As such, this move will enhance operational efficiency with other public safety partners, improve interagency collaboration, and position the department for future growth,” Martin said.

The headquarters move has been in the making for over five years. Public safety officials said the old building on Woodrow Wilson fell into disrepair after years of neglect.

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, was part of a group of lawmakers who proposed moving the headquarters to a different location inside Jackson.

“I personally think that the state government should be based in the state capital,” he said.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Driver's license office moves to downtown Jackson appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article from *Mississippi Today* offers a factual and neutral report on the relocation of the Jackson driver’s license office and the broader headquarters move by the Mississippi Department of Public Safety. It includes quotes from officials and everyday citizens without editorializing or promoting a specific viewpoint. The inclusion of Sen. David Blount’s comment presents a mild political contrast, but it is balanced and not framed in a confrontational or ideological way. The tone remains focused on public service logistics and community impact rather than political narrative.

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed5 days ago

Bread sold at Walmart, Kroger stores in TN, KY recalled over undeclared tree nut

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

Man shot and killed in Benton County, near Rogers

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed1 day ago

Aiken County family fleeing to Mexico due to Trump immigration policies

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Girls Hold Lemonade Stand for St. Jude Hospital | July 12, 2025 | News 19 at 10 p.m. – Weekend

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

Anti-ICE demonstrators march to Beaufort County Sheriff's Office

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

Police say couple had 50+ animals living in home

-

Mississippi Today1 day ago

Driver’s license office moves to downtown Jackson

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Coast judge upholds secrecy in politically charged case. Media appeals ruling.