Illustration courtesy of Ettore Mazza, CC BY-ND

William Taylor, University of Colorado Boulder; John Wendt, Oklahoma State University, and Joshua Miller, University of Cincinnati

Moose are on the loose in the southern Rockies.

In July 2025, a young wandering bull was captured roaming a city park in Greeley, Colorado. A spate of similar urban sightings alongside some aggressive moose encounters has elevated moose management and conservation into a matter of public debate, especially across metro Denver and the Colorado Front Range.

In Rocky Mountain National Park, a recent study found that moose and elk might be to blame for far-reaching changes to valley ecosystems, as their browsing reduces important plants like willows, depriving beavers of habitat and materials for their wetland engineering. Park wildlife are generally not managed through hunting, but the park has tried techniques like fencing moose away from wetland zones. Publicly, discussion has swirled around further mitigation measures to slow or eliminate moose populations.

At the heart of this debate is a basic question – do moose belong in the southern Rockies at all?

During much of the last century, moose were apparently rare in Colorado. The animals are absent from some early 20th century official wildlife tallies. Then, in 1978, the Colorado Division of Wildlife – now Colorado Parks and Wildlife – released a group of moose into North Park in north-central Colorado. At the time, biologists understood their efforts to be a reintroduction, but in the years since, wildlife managers have shifted their thinking about the place of moose in local ecosystems.

In the decades that followed, the moose expanded their range and numbers. Today, informal estimates by Colorado Parks and Wildlife put the moose population at around 3,500 animals. Under increased moose browsing pressure and a shifting climate, some mountain wetland environments are changing.

Helen H. Richardson/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Should these changes be thought of as human-made ecological wounds caused by releasing moose? The National Park Service seems to think so.

Statements from 2025 on the park service website, and other public messaging from wildlife officials, assert that Colorado has never supported a breeding population of moose – only the occasional transient visitor. The factual basis for this idea seems to hinge heavily on an unpublished internal report from 2015, which identified only a few archaeological or historical records of moose near the park.

We are a team of archaeologists, paleoecologists and conservation paleobiologists studying the ancient animals of the Rockies.

Understanding moose and their interactions with people centuries ago means carefully analyzing different traces that survive the passage of time. These can range from the bones of animals themselves to indirect clues preserved in everything from lake sediments to historical records.

Are moose actually native to Colorado?

As scientists studying the past, we know that reconstructing the ancient geographic ranges of animals is difficult. Archaeological sites with animal bones can be a great tool to understand the past, especially for tracing the food choices of ancient humans. But such sites can be rare, and even when they are well preserved and well studied, it can take lots of care and scientific research to identify the species of each bone.

Harder still is determining the intimate details of ancient animals’ lives, including how and where they lived, died or reproduced. Such key details can be especially opaque for moose, who are solitary and elusive. Because of this, moose may not end up in human diets, even where both species have established populations. A comprehensive review of archaeological sites from across Alaska and some areas of the Canadian Yukon, where moose are common today and have likely been present since the end of the last Ice Age, found that moose were nearly absent until the past few centuries. In fact, moose often comprised less than 0.1% of the total number of bones in very large collections, if they appeared at all. In some areas, cultural reasons like taboos against moose hunting can also prevent them from ending up in archaeological bone tallies.

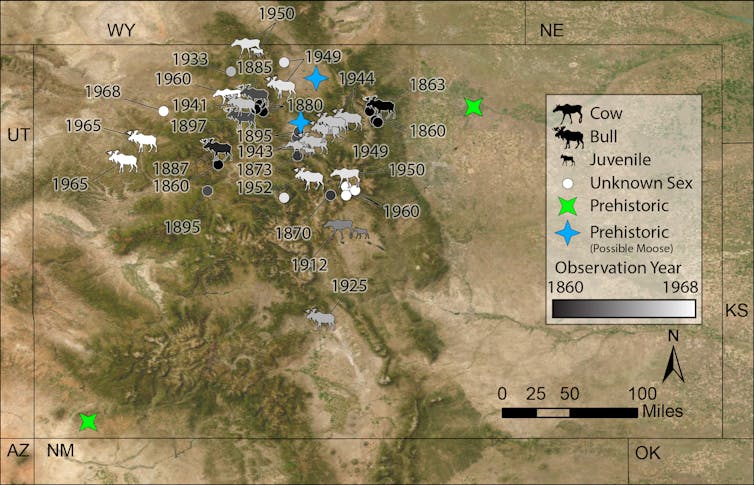

In new research published as a preprint in advance of peer review, we took a closer look at the idea that moose were absent from Colorado before 1978. We combed through newspaper records, photo archives and early travel diaries and identified dozens of references to moose sightings in Colorado spanning the first records in 1860 through the decade of moose reintroduction in the 1970s.

Moose sightings appear in the very earliest written records of the area that would become Rocky Mountain National Park. In his 1863 diary, Milton Estes described happening upon a large moose alongside a band of elk while on a hunting trip.

“Since elk were common I picked out Mr. Moose for my game,” he wrote.

Milton thought he had bagged “the first and only moose that had ever been killed so far south.” He was wrong.

Our archival research turned up even earlier sightings of moose in the area, along with many more across the region in the decades that followed. Diaries, newspapers and photo records from the past two centuries show the presence of not only young bulls, which at times can range widely, but also cows and calves, a sign that local breeding was taking place in Colorado before reintroduction.

These sightings recorded in diaries and newspapers don’t have to stand on their own. Moose appear in older placenames around the state, like the area once known as Moose Park along the road from Lyons to Estes Park. Written accounts from the late 19th and early 20th centuries among Ute, Shoshone and Arapaho peoples describe moose stories, hunts and songs. And though historical records don’t go too much further back than the mid-19th century in Colorado, archaeological records do.

Our survey of Colorado sites turned up ancient moose at Jurgens, near Greeley, dated to more than 9,000 years ago, and even moose bone tools among the ruins of Mesa Verde, only a few centuries ago.

This question of whether moose are native to the southern Rockies is not just a philosophical one – its answer will shape management decisions by the National Park Service and others.

Official narrative minimizes moose presence

The contemporary idea of moose as non-native animals reflects a different understanding than was common only a few decades ago. In the 1940s, some biologists described moose as a native species that had been “extirpated except for stragglers.” As recently as the early 1970s, Rocky Mountain National Park officials understood their moose work as a reintroduction of “wild animals once native to the park.” Our findings suggest that the valid knowledge of earlier scientists has since faded or been replaced, repositioning moose as ecological outsiders.

As moose-human conflicts and shifting wetland ecologies prompt hard conversations over how to manage moose, a range of options have been discussed in public discourse. These include courses of action such as the reintroduction of carnivores like wolves, or targeted hunting access for tribes or the public.

If moose are ‘invasive,’ they can be removed

For federal agencies, labels like “invasive” or “non-native” carry legal connotations and can be used to enable other measures, like eradication.

In Olympic National Park, where mountain goats were deemed invasive and ecologically impactful, biologists undertook an extermination campaign that involved shooting the animals from helicopters, despite warnings from archaeologists as long ago as the late 1990s that the data behind their argument was flawed.

As the animal and plant communities of our Rockies change rapidly in a warming world, this kind of policy would not only be unsupported by scientific evidence, but also likely to impede the ability of our animal communities to survive, adapt and thrive.

The historical evidence indicates that moose are not foreign intruders. Archival, archaeological and anthropological data shows that moose have been in the southern Rockies for centuries, if not millennia. Rather than treat moose as a threat, we urge Rocky Mountain National Park and other agencies to work in partnership with tribes, paleoecologists and the public to carefully develop historically grounded management plans for this Colorado native.

William Taylor, Assistant Professor and Curator of Archaeology, University of Colorado Boulder; John Wendt, Postdoctorial Fellow in Natural Resources Ecology and Management, Oklahoma State University, and Joshua Miller, Associate Professor of Geosciences, University of Cincinnati

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Helen H. Richardson/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Should these changes be thought of as human-made ecological wounds caused by releasing moose? The National Park Service seems to think so.

Statements from 2025 on the park service website, and other public messaging from wildlife officials, assert that Colorado has never supported a breeding population of moose – only the occasional transient visitor. The factual basis for this idea seems to hinge heavily on an unpublished internal report from 2015, which identified only a few archaeological or historical records of moose near the park.

We are a team of archaeologists, paleoecologists and conservation paleobiologists studying the ancient animals of the Rockies.

Understanding moose and their interactions with people centuries ago means carefully analyzing different traces that survive the passage of time. These can range from the bones of animals themselves to indirect clues preserved in everything from lake sediments to historical records.

Are moose actually native to Colorado?

As scientists studying the past, we know that reconstructing the ancient geographic ranges of animals is difficult. Archaeological sites with animal bones can be a great tool to understand the past, especially for tracing the food choices of ancient humans. But such sites can be rare, and even when they are well preserved and well studied, it can take lots of care and scientific research to identify the species of each bone.

Harder still is determining the intimate details of ancient animals’ lives, including how and where they lived, died or reproduced. Such key details can be especially opaque for moose, who are solitary and elusive. Because of this, moose may not end up in human diets, even where both species have established populations. A comprehensive review of archaeological sites from across Alaska and some areas of the Canadian Yukon, where moose are common today and have likely been present since the end of the last Ice Age, found that moose were nearly absent until the past few centuries. In fact, moose often comprised less than 0.1% of the total number of bones in very large collections, if they appeared at all. In some areas, cultural reasons like taboos against moose hunting can also prevent them from ending up in archaeological bone tallies.

In new research published as a preprint in advance of peer review, we took a closer look at the idea that moose were absent from Colorado before 1978. We combed through newspaper records, photo archives and early travel diaries and identified dozens of references to moose sightings in Colorado spanning the first records in 1860 through the decade of moose reintroduction in the 1970s.

Moose sightings appear in the very earliest written records of the area that would become Rocky Mountain National Park. In his 1863 diary, Milton Estes described happening upon a large moose alongside a band of elk while on a hunting trip.

“Since elk were common I picked out Mr. Moose for my game,” he wrote.

Milton thought he had bagged “the first and only moose that had ever been killed so far south.” He was wrong.

Our archival research turned up even earlier sightings of moose in the area, along with many more across the region in the decades that followed. Diaries, newspapers and photo records from the past two centuries show the presence of not only young bulls, which at times can range widely, but also cows and calves, a sign that local breeding was taking place in Colorado before reintroduction.

These sightings recorded in diaries and newspapers don’t have to stand on their own. Moose appear in older placenames around the state, like the area once known as Moose Park along the road from Lyons to Estes Park. Written accounts from the late 19th and early 20th centuries among Ute, Shoshone and Arapaho peoples describe moose stories, hunts and songs. And though historical records don’t go too much further back than the mid-19th century in Colorado, archaeological records do.

Our survey of Colorado sites turned up ancient moose at Jurgens, near Greeley, dated to more than 9,000 years ago, and even moose bone tools among the ruins of Mesa Verde, only a few centuries ago.

This question of whether moose are native to the southern Rockies is not just a philosophical one – its answer will shape management decisions by the National Park Service and others.

Official narrative minimizes moose presence

The contemporary idea of moose as non-native animals reflects a different understanding than was common only a few decades ago. In the 1940s, some biologists described moose as a native species that had been “extirpated except for stragglers.” As recently as the early 1970s, Rocky Mountain National Park officials understood their moose work as a reintroduction of “wild animals once native to the park.” Our findings suggest that the valid knowledge of earlier scientists has since faded or been replaced, repositioning moose as ecological outsiders.

Isaac Hart/Taylor et al. in review

As moose-human conflicts and shifting wetland ecologies prompt hard conversations over how to manage moose, a range of options have been discussed in public discourse. These include courses of action such as the reintroduction of carnivores like wolves, or targeted hunting access for tribes or the public.

If moose are ‘invasive,’ they can be removed

For federal agencies, labels like “invasive” or “non-native” carry legal connotations and can be used to enable other measures, like eradication.

In Olympic National Park, where mountain goats were deemed invasive and ecologically impactful, biologists undertook an extermination campaign that involved shooting the animals from helicopters, despite warnings from archaeologists as long ago as the late 1990s that the data behind their argument was flawed.

As the animal and plant communities of our Rockies change rapidly in a warming world, this kind of policy would not only be unsupported by scientific evidence, but also likely to impede the ability of our animal communities to survive, adapt and thrive.

The historical evidence indicates that moose are not foreign intruders. Archival, archaeological and anthropological data shows that moose have been in the southern Rockies for centuries, if not millennia. Rather than treat moose as a threat, we urge Rocky Mountain National Park and other agencies to work in partnership with tribes, paleoecologists and the public to carefully develop historically grounded management plans for this Colorado native.