Mississippi Today

Mississippi University for Women is betting its future on a new name. Will it work?

COLUMBUS — Nora Miller, the president of Mississippi University for Women, opened a letter from her deans in 2022 that warned the country’s first state-supported women’s college had reached a critical crossroads.

Without bold change, the deans wrote, the pool of prospective students was “likely to grow dangerously thin,” affecting tuition. Their recommendation: Change the name to one that includes all students, not just women. After all, the university had been co-ed since 1982.

One consulting firm, three listening sessions, 4,300 survey responses, one failed proposal, and one apology later, MUW will ask lawmakers to approve a new name next month. But as the institution seeks to reposition itself to meet an uncertain moment for higher education in Mississippi, it has faced criticism from some alumni, passionate about the past, who have questioned if a new name is needed at all.

Lost in the hullabaloo is the fact MUW faces much bigger issues than its name, according to more than a dozen interviews Mississippi Today conducted with students, faculty, administrators and alumni.

Enrollment has continued to fall since the dean’s letter. All told, the campus has shrunk to just 2,227 students from its peak of more than 3,100 in the late 1990s. The tuition-dependent university has been operating at a deficit, losing $18 million in fiscal year 2022. And it likely can’t turn to the state for help: Mississippi’s state funding for higher education has barely recovered from the Great Recession of 2008. The liberal arts education that MUW offers is increasingly pooh-poohed by lawmakers and other state officials who view workforce development as “the message of the day.”

To be sure, all of Mississippi’s regional colleges are struggling, so MUW’s plight isn’t totally unique. But within thirty miles of its doorstep, MUW is facing a hydra — a behemoth SEC school, a booming industrial park and a flourishing community college — all while dealing with a name that excludes roughly half of the students it wants to admit.

“It’s kind of like false advertising, isn’t it?” said Dee Anne Larson, a marketing professor on the university’s naming committee.

The university has acknowledged it needs to do a better job of selling what it offers: Comparatively affordable tuition, small class sizes and a familial campus. It has revamped its recruitment strategies, brought back athletics and pumped money into professional programs like culinary arts, speech language pathology and nursing.

“While we would prefer not running at a deficit,” Miller said, “sometimes you have to invest in things.”

Signs of that investment, though, are hard to spot. North on Highway 25, a brick sign for Starkville brags of being the “home of Mississippi State University.” Over the Lowndes County line, at the Golden Triangle Global Industrial Aerospace Park, is East Mississippi Community College’s glassy “communiversity” and its LED marquee.

The sign for Columbus, called the “friendly city,” makes no mention of MUW. The university employs hundreds of people in the region, a fact belied by its quiet presence.

Miller acknowledged workforce development programs entice high school graduates. But, she said, when younger workers from Steel Dynamics get tired, they’ll start looking for a pathway to office jobs.

“And I think some of those steelworkers aren’t gonna take advantage of that” at MUW, Miller said, “because ‘Mississippi University for Women’ will be on their degree.”

Cutting ties with the long blue line?

When MUW sent Miller an offer letter in 1979, she thought it was for a “finishing school” and threw it in the trash. Her mom convinced Miller, a National Merit Scholarship semifinalist, to take a second look.

Three years later, when the Institutions of Higher Learning Board of Trustees ordered MUW to admit men following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the university’s admissions policy, Miller’s first thought was “at least we get to keep the name.”

Then state-supported women’s colleges across the country started taking “women” out of their names. MUW didn’t in large part because the university’s leadership failed to get alumni on board. Even though the university has changed its name four times throughout its history — it was originally the Industrial Institute and College for the Education of White Girls — the alumni just couldn’t let go of “The W.”

Many still can’t.

Earlier this month, the university’s first proposal, Mississippi Brightwell University, flopped. The feedback was resoundingly negative.

That’s when an unofficial group of alumni started discussing an alternate proposal: “The W: A Mississippi University.” It seemed to capture the campus’s Ivy League aspirations, said Laura Tubb Prestwick, who graduated in 2008, works in brand-name strategy and was part of the unofficial group.

There’s an emotional stake in changing the name for “W girls” like Prestwick, whose grandmother also attended. Prestwick grew up going to modeling, photography and musical theater camps at MUW, and reading old copies of the “Meh Lady” yearbooks.

“When Tropicana changed their packaging, they saw a 20% drop in sales,” Prestwick said. “That’s an emotional tie to orange juice. Can you fathom it being somewhere you took out student loans for?”

Facing the demographic cliff

But MUW can’t sustain itself solely off the pockets of legacy students like Prestwick.

In Mississippi, as in nearly every state in the country, the number of high school graduates is poised to decline, an ominous trend deemed the “enrollment cliff.” This will force increased competition among Mississippi’s eight public universities, all of which are already more dependent on tuition than state funding, and 15 community colleges.

The future winners of that fight are laying the groundwork today. And MUW is already on the backfoot.

More than 200 freshmen used to enroll in MUW each year, according to the university. But since 2009, when EMCC’s Golden Triangle campus started a tuition-guarantee program, MUW is lucky if the freshman class broaches 200 at all. In the last decade, MUW has lost 600 undergrads — while down the road, Mississippi State University has seen undergraduate enrollment nearly triple that same amount. Meanwhile, last fall EMCC saw its largest enrollment increase in more than a decade.

The bleeding shows no signs of stopping. But MUW has been retooling its approach. In fall 2022, Miller promoted the longtime head of student success, David Brooking, to executive director of enrollment management.

One of the first things Brooking noticed was that MUW needed to do more outreach. The university was buying mailing lists to send letters like the kind Miller got in high school, but not nearly enough names — just 10,000 students when it needed more like 50,000. Brooking fixed that and has expanded MUW’s digital advertising, which he says is the way to reach the introverted, studious high schoolers who’d thrive at MUW.

Showing up at college fairs in parts of Mississippi with a growing population has been a challenge. The recruiting position assigned to the Coast, nearly five hours from Columbus, had been open since September, but only one person applied. Brooking plans to repost it as a remote job.

Even when MUW is present, the name impedes the elevator pitch.

“You only get two or three minutes to talk to a student at a college fair, if they’re even showing interest,” Brooking said. “We have to tell them what we’re not before we can tell them what we are.”

Brooking’s new approach isn’t expected to bear fruit until this fall, Miller said. In the meantime, students can tell the campus is emptier. Laila Wrenn, a member of the student government and a resident assistant, has noticed there are fewer freshmen in the dorms.

A junior on the pre-med track, Wrenn came to MUW for its close-knit campus, but she gets why others don’t.

“It’s just not fitting what they wanted college to be, kind of how they portray college on TV,” she said. “When you’re at the W, it doesn’t fit that picture. It’s not a party school. People commute here. It’s really quiet and it’s down to earth, and I feel like a lot of people aren’t attracted to that.”

MUW does have one powerful tool on its side — cost. At $7,766, it has the second lowest tuition for a public university in Mississippi. (In contrast, a year of tuition at Mississippi State runs $9,400.)

“If you’re gonna quote me on anything about that college,” said Ryan Ahrens, who graduated from MUW in 2021 with a business degree, “it is for sure and without a doubt the bargain of the century.”

Competing for men — literally

Ahrens, a Lowndes County native and transfer from East Mississippi Community College, was the exact kind of student MUW has been desperate to attract. And yet, he ended up there by accident.

“I missed the admissions window for State, and then I said at least the W is still open,” he said.

The university’s name is one reason it has struggled more than other former women-only colleges to attract men, according to a 2009 study commissioned when a past president, Claudia Limbert, sought to change the name. Since 1990, MUW has barely moved the needle on the number of men it admits, from 442 to 532 in 2020.

For his part, Ahrens thought the two-year renaming process moved too quickly. But alumni don’t control the school, he said.

“It’s not our job to have a hand in the pot, it’s our job to make the pot full,” he said. “In order for you to be proud of the university that you graduated from, it still has to be there decades after you leave it.”

But the name is far from the only area of improvement Ahrens sees. He listed several things that, as a conservative, white member of a fraternity, he saw could be improved: The dorms, the outreach and a vibe he described as “a stern ‘what are you doing here’ kind of look.”

“If you’re a man going through the W, you gotta go in with a strong mind and a thick skin cause people are gonna talk crap, like ‘you’re just another W girl,’’ Ahrens said. “Like no man, I’m a man.”

And then there are sports. Changing the name, Ahrens said, is the hardest thing an MUW president has attempted to do since getting into the NCAA last year. Bringing back sports, which the university disbanded in 2003, is part of an effort to attract more students.

It’s unclear if it’s working yet. Josh Dukes, a sophomore shooting guard from Booneville whose high school basketball team won the state championship, was enticed by the opportunity to help build MUW’s program from the ground up.

But his family of five brothers (and one sister) jokes that Dukes is playing “women’s basketball.” The team has a losing record. The university’s name makes it easier for other players, Dukes said, to “get inside your head.”

Losing its home turf

There is an elephant-sized bulldog in the room.

When Miller attended MUW in the 1980s, it had a complementary relationship to Mississippi State. Male students would come to Columbus to drink and eat out, because Lowndes County was wet and Oktibbeha County was dry. Female students would go to Starkville for the games.

It’s more competitive now.

Today, MSU is roaring, enjoying record enrollments, major success in fundraising and a slew of new construction projects. It is also raking in an increasing share of the number of college students who hail from Lowndes County, making MUW the only regional college in Mississippi at risk of losing its home turf.

In 2022, 450 students went to MUW compared to 432 to MSU, according to IHL data.

MUW is like a tiny planet that may be fated to fall into MSU’s orbit.

“They’ve got more gravitational pull than we do being so close to them,” Brooking said.

IHL classifies MUW as a “regional college,” yet MUW’s leaders know that in many ways, they are outmatched by MSU and EMCC. MUW must own its backyard, Miller said, but it also needs a name that can attract students from across the state and the South, one that gets at the one thing the small campus has: A private-college feel on a state-dollar dime that is accessible to all.

“At Mississippi State or Ole Miss, you might be intimidated … by the people with connections,” Miller said. “Others might say, ‘I couldn’t compete against that.’ But here, we nurture people taking on responsibility and getting to be a leader.”

But is that message connecting with Mississippians?

In downtown Columbus, where the number of local businesses rival Oxford’s Square, Naiya Bell, a 21-year-old community college student who was looking for jobs with her friends, said she had considered MUW’s nursing program.

But Brenda Heard, a landlord dropping off dry-cleaning who lives in Alabama, leases to MUW students but didn’t know if the university admitted men. Roderick Dillard, a firefighter, said his daughters went to MSU for the experience.

“Kids like to get out,” Dillard said.

Naomi Simpson and Angel Viveros students from the academically rigorous Mississippi School for Math and Science, were walking into a local bookstore as they recalled their high school’s recent college fair, which was held in MUW’s gym. Simpson listed off the tables she recalled Mississippi State having: Agriculture, the honors college, education and more.

Then Simpson paused. For a moment, neither student could remember if MUW was there, too. It was, Viveros remembered.

Simpson shrugged. “Maybe I just didn’t go up to them.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=327817

Mississippi Today

Trump nominates Baxter Kruger, Scott Leary for Mississippi U.S. attorney posts

President Donald Trump on Tuesday nominated Baxter Kruger to become Mississippi’s new U.S. attorney in the Southern District and Scott Leary to become U.S. attorney for the Northern District.

The two nominations will head to the U.S. Senate for consideration. If confirmed, the two will oversee federal criminal prosecutions and investigations in the state.

Kruger graduated from the Mississippi College School of Law in 2015 and was previously an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District. He is currently the director of the Mississippi Office of Homeland Security.

Sean Tindell, the Mississippi Department of Public Safety commissioner, oversees the state’s Homeland Security Office. He congratulated Kruger on social media and praised his leadership at the agency.

“Thank you for your outstanding leadership at the Mississippi Office of Homeland Security and for your dedicated service to our state,” Tindell wrote. “Your hard work and commitment have not gone unnoticed and this nomination is a testament to that!”

Leary graduated from the University of Mississippi School of Law, and he has been a federal prosecutor for most of his career.

He worked for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Tennessee in Memphis from 2002 to 2008. Afterward, he worked at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Mississippi in Oxford, where he is currently employed.

Leary told Mississippi Today that he is honored to be nominated for the position, and he looks forward to the Senate confirmation process.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Trump nominates Baxter Kruger, Scott Leary for Mississippi U.S. attorney posts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a straightforward news report on President Donald Trump’s nominations of Baxter Kruger and Scott Leary for U.S. attorney positions in Mississippi. It focuses on factual details about their backgrounds, qualifications, and official responses without employing loaded language or framing that favors a particular ideological perspective. The tone is neutral, with quotes and descriptions that serve to inform rather than persuade. While it reports on a political appointment by a Republican president, the coverage remains balanced and refrains from editorializing, thus adhering to neutral, factual reporting.

Mississippi Today

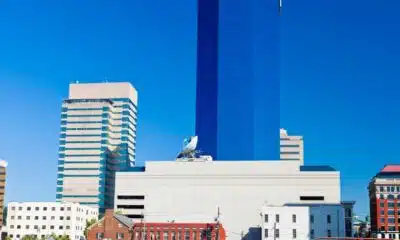

Jackson’s performing arts venue Thalia Mara Hall is now open

After more than 10 months closed due to mold, asbestos and issues with the air conditioning system, Thalia Mara Hall has officially reopened.

Outgoing Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba announced the reopening of Thalia Mara Hall during his final press conference held Monday on the arts venue’s steps.

“Today marks what we view as a full circle moment, rejoicing in the iconic space where community has come together for decades in the city of Jackson,” Lumumba said. “Thalia Mara has always been more than a venue. It has been a gathering place for people in the city of Jackson. From its first class ballet performances to gospel concerts, Thalia Mara Hall has been the backdrop for our city’s rich cultural history.”

Thalia Mara Hall closed last August after mold was found in parts of the building. The issues compounded from there, with malfunctioning HVAC systems and asbestos remediation. On June 6, the Mississippi State Fire Marshal’s Office announced that Thalia Mara Hall had finally passed inspection.

“We’re not only excited to have overcome many of the challenges that led to it being shuttered for a period of time,” Lumumba said. “We are hopeful for the future of this auditorium, that it may be able to provide a more up-to-date experience for residents, inviting shows that people are able to see across the world, bringing them here to Jackson. So this is an investment in the future.”

In total, Emad Al-Turk, a city contracted engineer and owner of Al-Turk Planning, estimates that $5 million in city and state funds went into bringing Thalia Mara Hall up to code.

The venue still has work to be completed, including reinstalling the fire curtain. The beam in which the fire curtain will be anchored has asbestos in it, so it will have to be remediated. In addition, a second air-conditioning chiller needs to be installed to properly cool the building. Until it’s installed, which could take months, Thalia Mara Hall will be operating at a lower seating capacity of about 800.

“Primarily because of the heat,” Al-Turk said. “The air conditioning would not be sufficient to actually accommodate the 2,000 people at full capacity, but starting in the fall, that should not be a problem.”

Al-Turk said the calendar is open for the city to begin booking events, though none have been scheduled for July.

“We’re very proud,” he said. “This took a little bit longer than what we anticipated, but we had probably seven or eight different contractors we had to coordinate with and all of them did a superb job to get us where we are today.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Jackson’s performing arts venue Thalia Mara Hall is now open appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a straightforward report on the reopening of Thalia Mara Hall in Jackson, focusing on facts and statements from city officials without promoting any ideological viewpoint. The tone is neutral and positive, emphasizing the community and cultural significance of the venue while detailing the challenges overcome during renovations. The coverage centers on public investment and future prospects, without partisan framing or editorializing. While quotes from Mayor Lumumba and a city engineer highlight optimism and civic pride, the article maintains balanced, factual reporting rather than advancing a political agenda.

Mississippi Today

‘Hurdles waiting in the shadows’: Lumumba reflects on challenges and triumphs on final day as Jackson mayor

On his last day as mayor of Jackson, Chokwe Antar Lumumba recounted accomplishments, praised his executive team and said he has no plans to seek office again.

He spoke during a press conference outside of the city’s Thalia Mara Hall, which was recently cleared for reopening after nearly a year of remediation. The briefing, meant to give media members a peek inside the downtown theater, marked one of Lumumba’s final forays as mayor.

Longtime state Sen. John Horhn — who defeated Lumumba in the Democratic primary runoff — will be inaugurated as mayor Tuesday, but Lumumba won’t be present. Not for any contentious reason, the 42-year-old mayor noted, but because he returns to his private law practice Tuesday.

“I’ve got to work now, y’all,” Lumumba said. “I’ve got a job.”

Thalia Mara Hall’s presumptive comeback was a fitting end for Lumumba, who pledged to make Jackson the most radical city in America but instead spent much of his eight years in office parrying one emergency after another. The auditorium was built in 1968 and closed nearly 11 months ago after workers found mold caused by a faulty HVAC system – on top of broken elevators, fire safety concerns and vandalism.

“This job is a fast-pitched sport,” Lumumba said. “There’s an abundance of challenges that have to be addressed, and it seems like the moment that you’ve gotten over one hurdle, there’s another one that is waiting in the shadows.”

Outside the theater Monday, Lumumba reflected on the high points of his leadership instead of the many crises — some seemingly self-inflicted — he faced as mayor.

He presided over the city during the coronavirus pandemic and the rise in crime it brought, but also the one-two punch of the 2021 and 2022 water crises, exacerbated by the city’s mismanagement of its water plants, and the 18-day pause in trash pickup spurred by Lumumba’s contentious negotiations with the city council in 2023.

Then in 2024, Lumumba was indicted alongside other city and county officials in a sweeping federal corruption probe targeting the proposed development of a hotel across from the city’s convention center, a project that has remained stalled in a 20-year saga of failed bids and political consternation.

Slated for trial next year, Lumumba has repeatedly maintained his innocence.

The city’s youngest mayor also brought some victories to Jackson, particularly in his first year in office. In 2017, he ended a furlough of city employees and worked with then-Gov. Phil Bryant to avoid a state takeover of Jackson Public Schools. In 2019, the city successfully sued German engineering firm Siemens and its local contractors for $89 million over botched work installing the city’s water-sewer billing infrastructure.

“I think that that was a pivotal moment to say that this city is going to hold people responsible for the work that they do,” Lumumba said.

Lumumba had more time than any other mayor to usher in the 1% sales tax, which residents approved in 2014 to fund infrastructure improvements.

“We paved 144 streets,” he said. “There are residents that still are waiting on their roads to be repaved. And you don’t really feel it until it’s your street that gets repaved, but that is a significant undertaking.”

And under his administration, crime has fallen dramatically recently, with homicides cut by a third and shootings cut in half in the last year.

Lumumba was first elected in 2017 after defeating Tony Yarber, a business-friendly mayor who faced his own scandals as mayor. A criminal justice attorney, Lumumba said he never planned to seek office until the stunning death of his father, Chokwe Lumumba Sr., eight months into his first term as mayor in 2014.

“I can say without reservation, and unequivocally, we remember where we started. We are in a much better position than we started,” Lumumba said.

Lumumba said he has sat down with Horhn in recent months, answered questions “as extensively as I could,” and promised to remain reachable to the new mayor.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'Hurdles waiting in the shadows': Lumumba reflects on challenges and triumphs on final day as Jackson mayor appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article reports on outgoing Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba’s reflections without overt editorializing but subtly frames his tenure within progressive contexts, emphasizing his self-described goal to make Jackson “the most radical city in America.” The piece highlights his accomplishments alongside challenges, including public crises and a federal indictment, maintaining a factual tone yet noting contentious moments like labor disputes and governance issues. While it avoids partisan rhetoric, the focus on social justice efforts, infrastructure investment, and crime reduction, as well as positive framing of Lumumba’s achievements, aligns with a center-left perspective that values progressive governance and accountability.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Defendant in auditor’s ‘second largest’ embezzlement case in history goes free

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

Are you addicted to ‘fridge cigarettes’? Here’s what the Gen Z term means

-

The Conversation6 days ago

Toxic algae blooms are lasting longer than before in Lake Erie − why that’s a worry for people and pets

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed6 days ago

5 teen boys caught on video using two stolen cars during crash-and-grab at Memphis gas station

-

Local News6 days ago

St. Martin trio becomes the first females in Mississippi to sign Flag Football Scholarships

-

Local News6 days ago

Mississippi Power shares resources and tips for lowering energy bill in the summer

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Error that caused Medicaid denials has been corrected, says cabinet in response to auditor letter

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

GOP mega-bill stuck in US Senate as disputes grow over hospitals and more