Mississippi News

Mississippi mental health services report released

Some mentally ill Mississippians wait in jail for hospital beds, report finds

Last winter, a George County woman spent weeks waiting in jail for a bed at a mental health facility.

Civil commitment – when a local court orders someone to be hospitalized for treatment – is supposed to be used when a person with a serious mental illness is in crisis, not when someone has addiction, an intellectual disability or dementia. The George County woman’s diagnosis was “major neurocognitive disorder,” an umbrella term that includes dementia.

In September 2021, local Community Mental Health Center staff recommended against hospitalizing her.

The court committed her anyway – twice. The first time, in October, she was discharged after about two weeks. The second time, in late November, she waited in the George County jail until at least Jan. 6. Eventually, the state hospital informed county officials she did not qualify for treatment there.

Her story – without a name or other identifying details – was included in the first report by the court-appointed monitor tasked with evaluating Mississippi’s mental health services at the community level. A judge appointed the monitor following the U.S. Department of Justice’s 2016 lawsuit against the state of Mississippi for violating federal law by not providing adults with mental illness with community services.

So far, the monitor found, the picture of how the services are working remains incomplete, with key data unavailable until later this year. That data includes commitment statistics by county, information on the number of people receiving services across counties, and calls to mobile crisis teams and the outcomes of those calls.

But it’s not uncommon for people like the woman in George County to spend days or weeks in jail because treatment is not readily available.

The monitor, Michael Hogan, noted that the state has reduced the number of people hospitalized and the length of stays. It has also provided funding for services at the Community Mental Health Centers, though not all of the programs are up and running – and whether the reduced hospitalizations means people are accessing community services instead is not yet clear.

“Given the early timing of this Report, and despite a number of efforts by the State to expand and improve care, it is not yet possible to make definitive determinations of compliance for many requirements of the Order,” he wrote.

He highlighted problems with the civil commitment process, including the widespread practice of sending people to jail to wait for a bed at a state hospital. He also described cases in which people with disabilities, dementia and addiction challenges, not serious mental illness, were committed.

In 2019, a federal court found that Mississippi had violated the rights of people with mental illnesses through a practice of hospitalizing them instead of providing services closer to home. Last year, U.S. District Court Judge Carlton W. Reeves approved a remedial plan for the state and appointed Hogan to compile compliance reports every six months.

Hogan described his first, filed with the court on Friday, as a “stage setting” report, providing background on the state’s mental health system and preliminary information on the availability of services. Parts of the plan have been paused as Mississippi appeals Reeves’ ruling to the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals.

In an email to Mississippi Today, Department of Mental Health Communications Director Adam Moore said the agency had “appreciated working with Dr. Hogan” during his review and providing the data he requested. Moore noted Hogan found low rates of hospital admissions among the hundreds of people served by the state’s community treatment teams for people with severe mental illness. The agency is also continuing its review of programs listed in the judge’s order.

“DMH is committed to continuing to make improvements in the system,” he wrote.

To prepare his report, Hogan visited three state hospitals and six of the state’s 13 CMHCs, which serve as the hubs for locally-based mental health services.

The Department of Mental Health encourages families to reach out to their local CMHC to get help for a loved one in crisis before considering civil commitment.

If someone believes a loved one or relative poses a danger to themselves or others, or that they need treatment to avoid deteriorating, they can file an affidavit with the local chancery clerk seeking to have the person committed. Then a judge determines whether they should be hospitalized.

If the judge decides the person should be committed, they’re supposed to get treatment at a state hospital or a crisis stabilization unit (CSU), where people can receive mental health care that may eliminate the need for hospitalization. But often, no bed is immediately available.

Hogan reviewed records for 21 people that included information about where they stayed prior to being admitted for treatment. While the majority waited in hospitals or CSUs, nine of them waited in jail. The longest wait recorded was 18 days.

“We do not know if statewide data on this is reviewed by DMH; the pattern needs attention,” he wrote.

Hogan’s report did not say how many people are committed every year statewide.

Hogan reviewed 25 sets of patient records that included a discharge diagnosis. In eight cases—nearly a third—the diagnosis was not serious mental illness but something else, including substance use disorder and intellectual or developmental disability.

Psychiatric hospitals are not generally equipped to provide inpatient treatment for such conditions, Hogan said.

“Their admission to Hospitals is stressful for them, a challenge for staff, and their interactions with people with SMI [serious mental illness] may be problematic,” he wrote, noting his sample size was too small to draw broad conclusions.

Moore said DMH had recently provided training to local judicial officials on mental health services and alternatives to civil commitment.

Planning for a patient’s discharge and continued care in their community is supposed to begin within 24 hours of their hospitalization, according to the court’s order. Hogan found that “progress is evident.” Hospital staff consistently arrange post-discharge appointments and send people home with a supply of medication and a prescription.

But Hogan also found shortcomings. Local mental health staff are supposed to meet with each person prior to being discharged from the hospital. He found little evidence that that was happening.

Many people are committed more than once: In Harrison County, 136 of the 338 people committed in 2020 had been through the process before – one of them 16 times. For people who have been committed within the past year, the court-ordered remedial plan requires discharge planning to include a review of previous plans and treatment so the new plan can be improved to reduce the likelihood of repeated institutionalization.

While that occurred at South Mississippi State Hospital, Hogan didn’t see that happening at the two other hospitals he reviewed.

In two cases where people were readmitted within a two-month period, Hogan wrote, both had legal problems “and there was pressure to ‘do something with them.’”

Moore said DMH plans to continue improving the discharge process, “including by partnering with the Community Mental Health Centers to complete intakes prior to discharge.”

Hogan’s review and the state’s expansion of community-based mental health services both took place against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has created a staffing shortfall at hospitals operated by the Department of Mental Health. A surge in COVID-19 cases also forced the cancellation of some of Hogan’s planned visits to CMHCs and state hospitals.

He praised the “valiant efforts” of state and local staff to provide care amid the challenges of health risks, staff shortages, and funding issues.

“This report comes at a time when we all hoped to be past the pandemic — but it continues,” he wrote in an acknowledgement at the beginning of the report. “The monitoring team acknowledges these challenges, and the burden placed on people who depend on and provide care. We applaud the courage of those who struggle on, and we mourn those who have been lost.”

Hogan’s next report will be published in September.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi News

Suspect in Charlie Kirk assassination believed to have acted alone, says Utah governor

SUMMARY: Tyler Robinson, 22, was arrested for the targeted assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk in Orem, Utah. Authorities said Robinson had expressed opposition to Kirk’s views and indicated responsibility after the shooting. The attack occurred during a Turning Point USA event at Utah Valley University, where Kirk was shot once from a rooftop and later died in hospital. Engravings on bullets and chat messages helped link Robinson to the crime, which was captured on grim video. The killing sparked bipartisan condemnation amid rising political violence. President Trump announced Robinson’s arrest and plans to award Kirk the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The post Suspect in Charlie Kirk assassination believed to have acted alone, says Utah governor appeared first on www.wjtv.com

Mississippi News

Americans mark the 24th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks with emotional ceremonies

SUMMARY: On the 24th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, solemn ceremonies were held in New York, at the Pentagon, and in Shanksville to honor nearly 3,000 victims. Families shared personal remembrances, emphasizing ongoing grief and the importance of remembrance. Vice President JD Vance postponed his attendance to visit a recently assassinated activist’s family, adding tension to the day. President Trump spoke at the Pentagon, pledging never to forget and awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously. The attacks’ global impact reshaped U.S. policy, leading to wars and extensive health care costs for victims. Efforts continue to finalize legal proceedings against the alleged plot mastermind.

The post Americans mark the 24th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks with emotional ceremonies appeared first on www.wcbi.com

Mississippi News

Hunt for Charlie Kirk assassin continues, high-powered rifle recovered

SUMMARY: Charlie Kirk, conservative influencer and Turning Point USA founder, was fatally shot by a sniper during a speech at Utah Valley University on September 10, 2025. The shooter, believed to be a college-aged individual who fired from a rooftop, escaped after the attack. Authorities recovered a high-powered rifle and are reviewing video footage but have not identified the suspect. The shooting highlighted growing political violence in the U.S. and sparked bipartisan condemnation. Kirk, a Trump ally, was praised by political leaders, including Trump, who called him a “martyr for truth.” The university was closed and security heightened following the incident.

The post Hunt for Charlie Kirk assassin continues, high-powered rifle recovered appeared first on www.wjtv.com

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

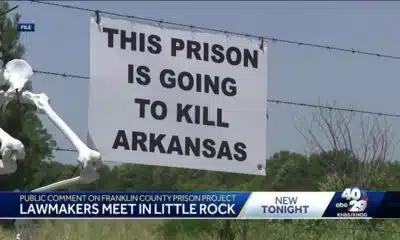

Group in lawsuit say Franklin county prison land was bought before it was inspected

-

The Center Square6 days ago

California mother says daughter killed herself after being transitioned by school | California

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Carly Gregg convicted of all charges

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

2025 Mississippi Book Festival announces sponsorship

-

Local News Video6 days ago

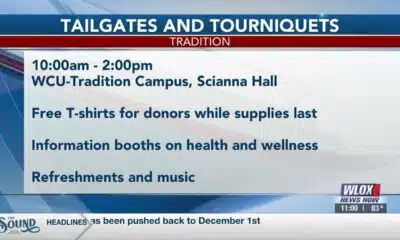

William Carey University holds 'tailgates and tourniquets' blood drive

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Local, statewide officials react to Charlie Kirk death after shooting in Utah

-

Local News6 days ago

US stocks inch to more records as inflation slows and Oracle soars