Mississippi Today

Meet Willye B. White: A Mississippian we should all celebrate

In an interview years and years ago, the late Willye B. White told me in her warm, soothing Delta voice, “A dream without a plan is just a wish. As a young girl, I had a plan.”

She most definitely did have a plan. And she executed said plan, as we shall see.

And I know what many readers are thinking: “Who the heck was Willye B. White?” That, or: “Willye B. White, where have I heard that name before?”

Well, you might have driven an eight-mile, flat-as-a-pancake stretch of U.S. 49E, between Sidon and Greenwood, and seen the marker that says: “Willye B. White Memorial Highway.” Or you might have visited the Olympic Room at the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and seen where White was a five-time participant and two-time medalist in the Summer Olympics as a jumper and a sprinter.

If you don’t know who Willye B. White was, you should. Every Mississippian should. So pour yourself a cup of coffee or a glass of iced tea, follow along and prepare to be inspired.

Willye B. White was born on the last day of 1939 in Money, near Greenwood, and was raised by grandparents. As a child, she picked cotton to help feed her family. When she wasn’t picking cotton, she was running, really fast, and jumping, really high and really long distances.

She began competing in high school track and field meets at the age of 10. At age 11, she scored enough points in a high school meet to win the competition all by herself. At age 16, in 1956, she competed in the Summer Olympics at Melbourne, Australia.

Her plan then was simple. The Olympics, on the other side of the world, would take place in November. “I didn’t know much about the Olympics, but I knew that if I made the team and I went to the Olympics, I wouldn’t have to pick cotton that year. I was all for that.”

Just imagine. You are 16 years old, a high school sophomore, a poor Black girl. You are from Money, Mississippi, and you walk into the stadium at the Melbourne Cricket Grounds to compete before a crowd of more than 100,000 strangers nearly 10,000 miles from your home.

She competed in the long jump. She won the silver medal to become the first-ever American to win a medal in that event. And then she came home to segregated Mississippi, to little or no fanfare. This was the year after Emmett Till, a year younger than White, was brutally murdered just a short distance from where she lived.

“I used to sit in those cotton fields and watch the trains go by,” she once told an interviewer. “I knew they were going to some place different, some place into the hills and out of those cotton fields.”

Her grandfather had fought in France in World War I. “He told me about all the places he saw,” White said. “I always wanted to travel and see the places he talked about.”

Travel, she did. In the late 1950s there were two colleges that offered scholarships to young, Black female track and field athletes. One was Tuskegee in Alabama, the other was Tennessee State in Nashville. White chose Tennessee State, she said, “because it was the farthest away from those cotton fields.”

She was getting started on a track and field career that would take her, by her own count, to 150 different countries across the globe. She was the best female long jumper in the U.S. for two decades. She competed in Olympics in Melbourne, Rome, Tokyo, Mexico City and Munich. She would compete on more than 30 U.S. teams in international events. In 1999, Sports Illustrated named her one of the top 100 female athletes of the 20th century.

Chicago became White’s home for most of adulthood. This was long before Olympic athletes were rich, making millions in endorsements and appearance fees. She needed a job, so she became a nurse. Later on, she became an public health administrator as well as a coach. She created the Willye B. White Foundation to help needy children with health and after school care.

In 1982, at age 42, she returned to Mississippi to be inducted into the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and was welcomed back to a reception at the Governor’s Mansion by Gov. William Winter, who introduced her during induction ceremonies. Twenty-six years after she won the silver medal at Melbourne, she called being hosted and celebrated by the governor of her home state “the zenith of her career.”

Willye B. White died of pancreatic cancer in a Chicago hospital in 2007. While working on an obituary/column about her, I talked to the late, great Ralph Boston, the three-time Olympic long jump medalist from Laurel. They were Tennessee State and U.S. Olympic teammates. They shared a healthy respect from one another, and Boston clearly enjoyed talking about White.

At one point, Ralph asked me, “Did you know Willye B. had an even more famous high school classmate.”

No, I said, I did not.

“Ever heard of Morgan Freeman?” Ralph said, laughing.

Of course.

“I was with Morgan one time and I asked him if he ever ran track,” Ralph said, already chuckling about what would come next.

“Morgan said he did not run track in high school because he knew if he ran, he’d have to run against Willye B. White, and Morgan said he didn’t want to lose to a girl.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Mississippi Today

‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious

Superintendent Errick Greene wanted to be very clear with the roughly 50 parents who attended Thursday night’s community listening session: Jackson Public Schools already has a policy banning students from using cellphones at school.

But the leadership of Mississippi’s third-largest school district has decided that a new approach is in order, citing a series of incidents in recent years involving students using their cellphones to bully others, organize fights or text their parents inaccurate information about violence happening at or near their school.

“To be clear, it’s not the majority of our scholars, but I can’t look at a class and know who’s gonna be bullying today, who’s gonna be scheduling a meetup to cut up today,” Greene said toward the end of the hour-long meeting held at the JPS board room. “I can’t look at a group of scholars and say, ‘OK, yeah, you’re the one, let me take your phone, the rest of you can keep it.’”

Under the rewritten policy, students who take their phone out of their backpacks during the instructional day will lose it for five days for the first infraction, 10 days for the second and 45 days for the third. Currently, the longest the school will hold a phone is 10 days.

The Jackson school board is expected to consider the new policy at its meeting next week and the district hopes to implement the change when the new school year starts later this month, said Sherwin Johnson, the district’s communications director.

Students also currently have the option to pay up to a $25 fine to get their phone back, but the district wants to rescind that aspect of the policy.

“We’ve discovered that’s not equitable,” said Larrisa Harris, the JPS general counsel. “Not everybody has the resources to come and pay the fine.”

Support for the new policy among the parents who spoke at the listening session varied, but all had questions. How will students access the internet on their laptops if the WiFi is spotty at their school and they need to use their cellphone hotspot? If students are required to keep their phones in their backpacks during lunch, how will teachers prevent stealing? How will JPS enforce the ban on using cellphones on the bus?

One mother said she watches her daughter’s location while she rides the bus to Jim Hill High School so she knows her daughter made it safely.

“If they can’t have it on the bus, who’s gonna enforce that?” she said. “I’m just gonna be real, the bus driver got to drive.”

A common theme among parents was anxiety at the prospect of losing direct contact with their kids in the event of an emergency. A Pew Research survey found that most adults, regardless of political affiliation, support cellphone bans in middle and high school classes. But those who don’t say it’s because their child can use their phone during emergencies.

“If something happened, will we get an automatic alert to notify us? Because a lot of the time we see things on social media first,” said Ashley McIntyre, a mother of three JPS students. She attended the meeting with her eldest daughter, Aaliyah, who recently graduated from Powell Middle School.

Though JPS does have an alert system for parents, McIntyre said she didn’t know if it existed. She cited a bomb threat at Powell last year that she found out about because Aaliyah texted her, not through a school alert.

“We didn’t know what was going on, and she texted me, ‘Mom, I’m scared,’ so I went up there,” McIntyre said. “So that puts us on edge.”

Aaliyah said she uses her phone to text her mom and watch TikTok, but she feels like her classmates use their phones to be popular or to fit in. When a fight happens, she said many students pull out their phones to record instead of trying to get an adult who can stop it. Then the videos end up on Instagram pages dedicated to posting fights in JPS.

“Once the principal found out about the fight pages, they came around looking inside our videos and camera rolls,” she said. “It happened to me last year. They thought I had a fight on my phone.”

Toward the end of the meeting, Laketia Marshall-Thomas, the assistant superintendent for high schools, took the mic to respond to one parent who said she was concerned that older students would not come to school if they knew their phone could be taken.

“What we have seen is, it’s the older students—” Marshall-Thomas began.

“They are the problem,” someone from the audience chimed in.

“We’re not saying they cannot have them,” she continued. “We know that they have after school activities and they need to communicate with their moms … but we have had major, major issues with cellphones and issues that have even resulted in criminal outcomes for our scholars, but most importantly, our students … have experienced a lot of learning loss.”

While the district leadership did not go into detail about the criminal incidents, several pointed to instances where students have texted their parents inaccurate information, such as an unsubstantiated rumor there was a gun during a fight at Callaway High School or that a shooting outside Whitten Middle School occurred on school property.

“Having phones actually creates far more chaos than they help anyone,” Greene said.

While cellphones have been banned to varying degrees in U.S. schools for decades, youth mental health concerns have renewed interest in more widespread bans across the country. Cellphone and social media usage among school-aged kids is linked to negative mental health outcomes and instances of cyberbullying, research shows.

At least 11 states restrict or ban cellphone use in schools. After Mississippi’s youth mental health task force recommended that all school districts implement policies that limited cellphone and social media usage in classrooms, a bill that would’ve required school boards to create cellphone policies died during the legislative session. Still, several Mississippi school districts have passed their own policies, including Marshall County and Madison County.

Another concern about the ban was a belief among a couple of speakers at the meeting that cellphones can help parents hold the district accountable for misdeeds it may want to hide.

“I just saw a video today. It was not in JPS, but it was a child being yelled at by the teacher and had he not recorded it, his momma would have never known that this sweet lady that they go to church with is degrading her child like that,” one mother said.

Statements like these prompted responses from teachers and other parents who urged the skeptical attendees to be more trusting or to make sure the district has updated contact information for them in case school officials need to reach parents during an emergency.

“I think we have to trust the people watching over our children,” said one of the few fathers who spoke. “When I grew up, what the teacher said was gold.”

One teacher asked the audience, “Will you trust us?”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post ‘Will you trust us?’: JPS plan for stricter cellphone policy makes some parents anxious appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a balanced report on Jackson Public Schools’ proposed stricter cellphone policy without taking a clear ideological stance. It fairly conveys the perspectives of school officials emphasizing discipline and safety, alongside parental concerns about communication and emergency access. The tone remains neutral, focusing on factual details such as policy changes, reasons behind them, and community reactions. While it includes some skepticism from parents and responses from district staff, the language does not endorse or oppose either side. Overall, the coverage adheres to neutral, factual reporting by presenting multiple viewpoints without editorializing.

Mississippi Today

Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts

Mississippi hospitals could lose up to $1 billion over the next decade under the sweeping, multitrillion-dollar tax and policy bill President Donald Trump signed into law last week, according to leaders at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

The leaders say the cuts could force some already-struggling rural hospitals to reduce services or close their doors.

The law includes the largest reduction in federal health and social safety net programs in history. It passed 218-214, with all Democrats voting against the measure and all but five Republicans voting for it.

In the short term, these cuts will make health care less accessible to poor Mississippians by making the eligibility requirements for Medicaid insurance stiffer, likely increasing people’s medical debt.

In the long run, the cuts could lead to worsening chronic health conditions such as diabetes and obesity for which Mississippi already leads the nation, and making private insurance more expensive for many people, experts say.

“We’ve got about a billion dollars that are potentially hanging in the balance over the next 10 years,” Mississippi Hospital Association President Richard Roberson said Wednesday during a panel discussion at his organization’s headquarters.

“If folks were being honest, the entire system depends on those rural hospitals,” he said.

Mississippi’s uninsured population could increase by 160,000 people as a combined result of the new law and the expiration of Biden-era enhanced subsidies that made marketplace insurance affordable – and which Trump is not expected to renew – according to KFF, a health policy research group.

That could make things even worse for those who are left on the marketplace plans.

“Younger, healthier people are going to leave the risk pool, and that’s going to mean it’s more expensive to insure the patients that remain,” said Lucy Dagneau, senior director of state and local campaigns at the American Cancer Society.

Among the biggest changes facing Medicaid-eligible patients are stiffer eligibility requirements, including proof of work. The new law requires able-bodied adults ages 19 to 64 to work, do community service or attend an educational program at least 80 hours a month to qualify for, or keep, Medicaid coverage and federal food aid.

Opponents say qualified recipients could be stripped of benefits if they lose a job or fail to complete paperwork attesting to their time commitment.

Georgia became the case study for work requirements with a program called Pathways to Coverage, which was touted as a conservative alternative to Medicaid expansion.

Ironically, the 54-year-old mechanic chosen by Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp to be the face of the program got so fed up with the work requirements he went from praising the program on television to saying “I’m done with it” after his benefits were allegedly cancelled twice due to red tape.

Roberson sent several letters to Mississippi’s congressional members in weeks leading up to the final vote on the sweeping federal legislation, sounding the alarm on what it would mean for hospitals and patients.

Among Roberson’s chief concerns is a change in the mechanism called state directed payments, which allows states to beef up Medicaid reimbursement rates – typically the lowest among insurance payors. The new law will reduce those enhanced rates to nearly as low as the Medicare rate, costing the state at least $500 million and putting rural hospitals in a bind, Roberson told Mississippi Today.

That change will happen over 10 years starting in 2028. That, in conjunction with the new law’s one-time payment program called the Rural Health Care Fund, means if the next few years look normal, it doesn’t mean Mississippi is safe, stakeholders warn.

“We’re going to have a sort of deceiving situation in Mississippi where we look a little flush with cash with the rural fund and the state directed payments in 2027 and 2028, and then all of a sudden our state directed payments start going down and that fund ends and then we’re going to start dipping,” said Leah Rupp Smith, vice president for policy and advocacy at the Mississippi Hospital Association.

Even with that buffer time, immediate changes are on the horizon for health care in Mississippi because of fear and uncertainty around ever-changing rules.

“Hospitals can’t budget when we have these one-off programs that start and stop and the rules change – and there’s a cost to administering a program like this,” Smith said.

Since hospitals are major employers – and they also provide a sense of safety for incoming businesses – their closure, especially in rural areas, affects not just patients but local economies and communities.

U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson is the only Democrat in Mississippi’s congressional delegation. He voted against the bill, while the state’s two Republican senators and three Republican House members voted for it. Thompson said in a statement that the new law does not bode well for the Delta, one of the poorest regions in the U.S.

“For my district, this means closed hospitals, nursing homes, families struggling to afford groceries, and educational opportunities deferred,” Thompson said. “Republicans’ priorities are very simple: tax cuts for (the) wealthy and nothing for the people who make this country work.”

While still colloquially referred to as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name was changed by Democrats invoking a maneuver that has been used by lawmakers in both chambers to oppose a bill on principle.

“Democrats are forcing Republicans to delete their farcical bill name,” Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer of New York said in a statement. “Nothing about this bill is beautiful — it’s a betrayal to American families and it’s undeserving of such a stupid name.”

The law is expected to add at least $3.3 trillion to the nation’s debt over the next 10 years, according to the most recent estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Hospitals see danger in Medicaid spending cuts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article reports on the negative impacts of a major federal tax and policy bill on Medicaid funding and rural hospitals in Mississippi. While it presents factual details and statements from stakeholders, the tone and framing emphasize the harmful consequences for vulnerable populations and health care access, aligning with concerns typically raised by center-left perspectives. The article highlights opposition by Democrats and critiques the bill’s priorities, particularly its effect on poor and rural communities, suggesting sympathy toward social safety net preservation. However, it maintains mostly factual reporting without overt partisan language, resulting in a moderate center-left bias.

Crooked Letter Sports Podcast

Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of ’25

The MSHOF will induct eight new members on Aug 2. Rick Cleveland has covered them all and he and son Tyler talk about what makes them all special.

Stream all episodes here.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Podcast: The Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame Class of '25 appeared first on mississippitoday.org

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

'Big Beautiful Bill' already felt at Georgia state parks | FOX 5 News

-

The Center Square5 days ago

Here are the violent criminals Judge Murphy tried to block from deportation | Massachusetts

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

Woman arrested in Morgantown McDonald’s parking lot

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

Hill Country flooding: Here’s how to give and receive help

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed7 days ago

Raleigh caps Independence Day with fireworks show outside Lenovo Center

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Shannon County Sheriff alleges ‘orchestrated campaign of harassment and smear tactics,’ threats to life

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

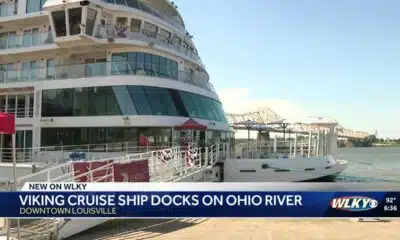

Cruising into Louisville: Viking cruise ship docks downtown on Ohio River

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

The Other Passionflower | Our Mississippi Home