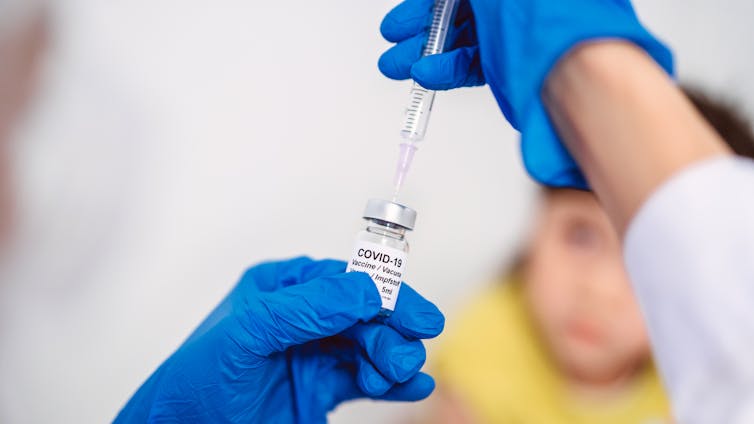

Solskin/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Kelly S. Mix, University of Maryland

Science funding is a hot topic these days and people have questions about how grants work. Who decides whether a researcher will receive funds? What’s the decision-making process? How is the money spent once a grant proposal has been approved?

As a veteran academic researcher, department chairperson and associate dean for research, I have seen this process play out from multiple perspectives – as a grant recipient, grant reviewer and university administrator.

Research organizations and major federal funders, including the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), all rely on careful systems of checks and balances to ensure high standards of scholarship and financial integrity at every stage of a grant’s lifecycle. Here’s how it all works.

The birth of a grant application

To receive research funding, scientists submit grant applications to specific programs. A cancer researcher might apply to the Bioengineering Research Grants program at NIH. Someone investigating sustainable fishing in freshwater habitats could seek funding from the Population and Community Ecology program at the NSF.

Applications must be responsive to the funding program’s specific request for proposals, or RFP. The RFP tells researchers what the agency wants to fund. For example, the NSF’s Education Core Research program currently only funds projects focused on STEM learning.

RFPs might have other application requirements, too, like explaining how a project will contribute to the public good, or supporting training for new scientists.

Grant applications have two main parts. First, the researcher presents an extensive literature review to explain why the new project is needed and what it will add to the existing knowledge base. Next, they write up a detailed description of the proposed research plan. This basic two-part structure ensures that funded research will yield important information that is both new and trustworthy.

Reviewers read the grant applications and compare them to the RFP. Applications that don’t address all the topics and research priorities listed there are unlikely to be funded. I once had a proposal rejected without further review because I left out a paragraph addressing one of the items in the agency’s new RFP. This initial review for RFP compliance is called “triage” and, believe me, nobody wants to see their hard work triaged out of the running.

PeopleImages/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Merit review: How funding decisions are made

Federal funding decisions are made through rigorous merit review.

For each round of funding, agencies assemble a panel of anonymous content experts who will look for strengths and weaknesses in the proposals – anything from innovation in the question posed to logical flaws in the hypotheses or technical problems with the planned data analyses. With a group of experts looking for every possible weakness, having your grant reviewed is a bit like running a gauntlet.

This careful review might help explain why 70% to 80% of grant applications typically go unfunded at agencies like the NIH and the NSF. But this level of scrutiny is necessary to prevent funding poorly designed or low-impact research.

Several safeguards head off bias or unethical influences during merit review.

First, reviewers must disclose any conflicts of interest with the pool of applicants before they can access the applications. Conflicts of interest can include situations like the reviewer having been the student of an applicant, the applicant and reviewer being divorced, or the proposal coming from the reviewer’s current institution.

When conflicts are identified, the reviewer can remain on the panel, but they are completely excluded from decisions related to that application. They cannot even be in the room when it is discussed.

Second, reviewers usually attend a meeting, supervised by program staff from the funding agency, where everyone debates the proposal’s merits before they score it. Sometimes panel members disagree in their initial critiques and use the meeting to hash out their differences. Other times, a reviewer might raise an important concern that others missed.

Group discussion helps ensure a transparent and thorough review. It also stops any single reviewer from dictating the fate of a proposal because everyone hears the discussion and then scores the proposal individually. Whether a reviewer thinks an application is outstanding or fatally flawed, they must convince the rest of the experts in the room for the group’s overall scores to be greatly affected.

Third, these discussions, along with the applications themselves and any written critiques, are strictly confidential. Reviewers sign written confidentiality agreements under penalty of perjury. This practice stops panelists from scoring political points by telling an applicant they defended their proposal, or divulging trade secrets and proprietary information.

Following the meeting, final decisions are made by program staff using the reviewers’ evaluations. Some agencies adhere closely to the reviewers’ numeric scores – like a grade – when making these decisions. Others ask reviewers to sort applications into “fundable” or “non-fundable” piles; program staff then have some discretion on the final decision. But all decisions are rooted in the peer critiques.

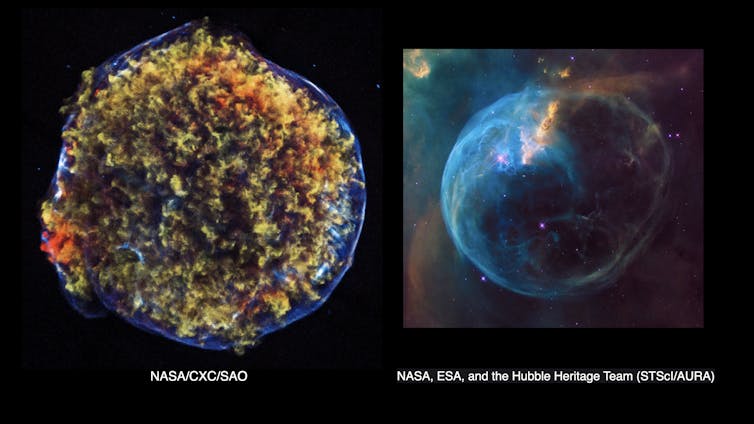

krisanapong detraphiphat/Moment

Spending the funds

Headlines about universities receiving large grants may leave the impression that such funds are simply added to the institution’s general coffers. But research funds are granted to support specific research projects, and agencies have strict rules about spending the money.

For example, if a researcher wants to present their findings at a conference, they can charge the grant for their travel costs, but they may not charge above a certain amount for their lodging or purchase business class airplane tickets. Similarly, if a researcher wants to have more time to devote to a funded project, they can use part of the money to pay their own salary in the summer, but there are precise limits on the amount of funding that can be used for this purpose.

It’s not up to the researcher alone to follow these rules. The organization that employs the researcher, usually a university, enforces the agency rules because it’s the employing organization that controls the grant accounts.

Returning to the conference travel example, a university researcher who wants to attend a conference must request permission and provide a budget for the trip before purchasing tickets. If the travel request is approved by their department chair, dean and the university travel office, they may go ahead with their reservations. However, if they don’t produce receipts when they return, they will not be allowed to charge the grant. The same process applies to buying new computers for the lab, ordering standardized tests for a study or purchasing gift cards for study participants.

Research organizations are highly motivated to enforce spending rules properly, because everyone in the organization is at risk of losing access to federal funds in the future if they let things slide. Funding agencies also require periodic reports and sometimes conduct audits to ensure compliance. These practices help guard against any misuse of funds.

The way agencies issue grants to researchers isn’t perfect. But processes like issuing detailed RFPs, conducting merit reviews and monitoring financial compliance go a long way toward protecting the integrity of the research funding process.

Kelly S. Mix, Associate Dean for Research, Innovation, and Partnerships in the College of Education, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.