Mississippi Today

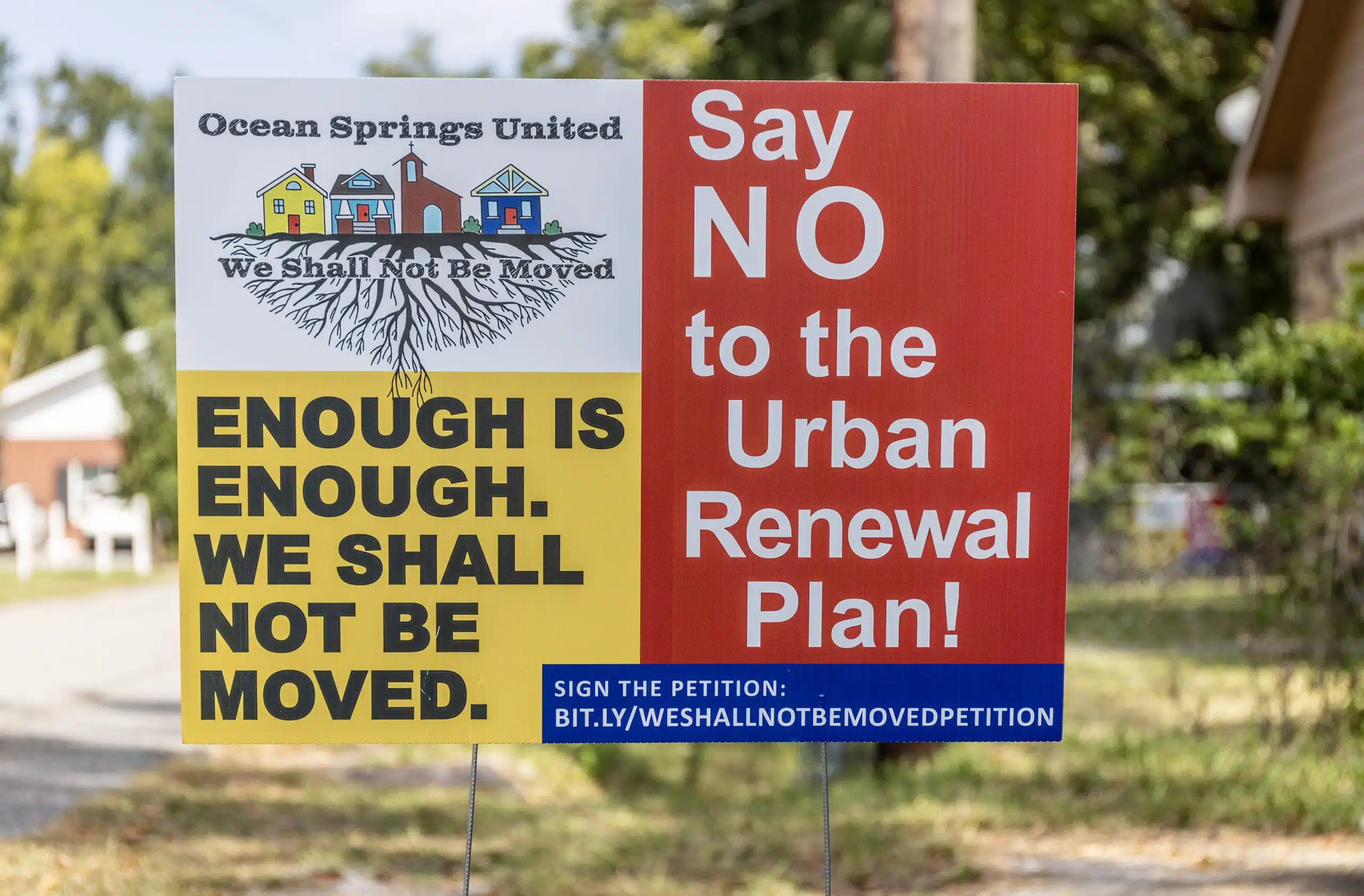

Lawsuit challenges Mississippi’s urban renewal law being used on Ocean Springs homes

A group of Ocean Springs residents, a business owner and a church all filed a lawsuit in federal court against the city on Thursday over an urban renewal plan that labeled certain properties as “slums” or “blighted.”

In April, the city gave that designation to over 100 properties around Ocean Springs. By doing so, the city paved the way to invoke a state law that allows the acquisition of such properties — with or without the owners’ permission — in order to remove “economic and social liability.” While many of the properties listed in the urban renewal plan are vacant lots, they also include occupied homes, businesses and the parking lot of a church in a historic Black neighborhood.

But residents say they didn’t find out about the plan until the city shared it on social media before a board meeting in August. The state law, according to Thursday’s lawsuit, allows just 10 days for residents to contest a “blighted” designation, meaning that Ocean Springs property owners missed their chance to do so because they only found out about the plan months later.

The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit law firm from Virginia that specializes in eminent domain cases, is representing the plaintiffs. The lawsuit is not just going after the city of Ocean Springs, but Mississippi’s laws around urban renewal in general.

“Mississippi law says you have to challenge the ‘blight’ designation in 10 days,” said IJ attorney Dana Berliner. “And people were contacting us (about the urban renewal plan) long after that. That is a violation of due process.”

Specifically, the complaint asks for judgments declaring the city violated the property owners’ rights to due process, that the city’s urban renewal plan is invalid, and that the state’s laws around urban renewal are unconstitutional.

After pushback following the August city board meeting, Mayor Kenny Holloway has repeatedly stated that the city won’t forcibly acquire anyone’s property. Holloway, who according to his city bio owns a real estate and development company, said last week at a public comment session that the city could’ve done a better job of communicating the intentions of the urban renewal plan. He added that the idea was to use federal grants to help make improvements around Ocean Springs.

It’s unclear what the city’s next steps are now that it’s facing a federal lawsuit. Holloway told the Sun Herald after last week’s meeting: “We’re not going to stop the plan. We’re going to try to find some common ground and move forward.”

But even if the city doesn’t use the plan to acquire residents’ home, or even if the city scraps the plan altogether, harm has already been done to those property owners, Berliner explained.

“Even if the current administration does nothing like that, (the ‘blight’ label) is going to be there 20 years later,” she said.

According to the state law, she said, the owners have no way of removing the label after the 10-day period, which means a future administration could still acquire the “blighted” properties under a new urban renewal plan.

Ocean Springs residents whose properties have belonged to their families for generations argue that their homes and land don’t meet the criteria for “blighted” areas.

“We’re proud of our neighborhood, and while we may not have a lot of money to put in our homes, we keep them well,” homeowner Cynthia Fisher said. “What the city did, labeling our neighborhood as a slum without telling us, was wrong.”

Fisher is a plaintiff in the case along with homeowners Esther Payton and Edward Williams. Robert Zellner, who owns an auto repair store in the designated “blighted” area, and the Macedonia Missionary Baptist Church, which owns the aforementioned parking lot, are also plaintiffs. A link to the full complaint can be found here.

Mississippi Today is working on ongoing coverage of this story.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=295794

Mississippi Today

DEI, campus culture wars spark early battle between likely GOP rivals for governor in Mississippi

Higher education — central to the public profiles of billionaire businessman Tommy Duff and State Auditor Shad White, two Republicans eyeing Mississippi’s governorship in 2027 — has already become a point of division between them.

Duff, in a recent interview, appeared to take a shot at White, saying politicians should focus on the jobs they currently hold, not future ambitions for higher office. White, in response, said Duff, while on the college board, helped implement diversity, equity and inclusion programs anathema to conservative Republican policy.

In Mississippi, issues such as diversity, equity and inclusion and other culture war battles roiling higher education have become a wedge issue in intraparty political spats, a legal fight unfolding in federal court and an ongoing effort to keep college students from leaving the state in droves.

Duff is considering a run for governor and has made higher education a top focus of his recent public appearances. He cites his budget stewardship during his stint on the state Institutions of Higher Learning Board from May 2015 to May 2024.

White, both through reports issued by his office and his own bully pulpit, has led a high-profile campaign for conservative reform of Mississippi’s higher education system.

Duff has hinted at the broad outlines of what could become a gubernatorial campaign agenda, but he has largely done so without offering specific policy proposals, citing the nearly 27 months remaining until Election Day in 2027. The gubernatorial race, Duff added in an interview with Mississippi Today, should not distract current state leaders interested in running from attending to the demands of their offices.

“I kind of wish all these people that want to be running that maybe have government jobs and responsibilities ought to tend to the ones they have,” Duff said. He didn’t name White, but the comment appeared to be a shot at him.

In response to Duff’s statement, White criticized Duff’s track record on the IHL Board.

“When Tommy Duff was on the board running our universities, he supported the creation of the DEI office at Ole Miss, on his watch the University Medical Center started an ‘LGBTQ Clinic’ which gave puberty blockers to transgender minors, and he voted to require the COVID shot for university employees before they were allowed to come back to work, so I sort of wish he would have done a better job when he was in his government position,” White said. “I’d have less to clean up.”

In a statement, Jordan Russell, a spokesperson for Duff, called White’s statement “blatantly false” but declined to comment further.

John Sewell, director of communications for the IHL, said the University of Mississippi’s Division of Diversity and Community Engagement was requested by the university and approved by the Board in April 2017

The University of Mississippi Medical Center’s now dissolved “LGBTQ clinic” was created in 2019, and an IHL Board vote was not required for its creation, Sewell said.

On the COVID-19 vaccine mandate, Sewell said the board voted against a systemwide mandate in August of 2021, but was then prompted to change course in response to federal regulations.

“The next month, President Biden issued an order demanding that federal contractors and subcontractors be vaccinated. To avoid losing federal research dollars, the Board voted in October 2021 that individuals considered federal contractors and subcontractors should comply with the executive order,” Sewell said.

Neither Duff nor White has formally entered the race for governor, but they have both said they are considering a run. Their experience, along with Mississippi’s specific economic challenges, suggests higher education could play a major role in shaping state politics for years to come.

Duff focuses on fiscal policies

In what Duff’s advisers characterized as the first political speech of his life earlier this month, he reminded the crowd of his tenure on the IHL Board.

Duff anchored his comments about his experience on the IHL Board in cost savings – a message that aligns with the Trump administration’s elevation of “government efficiency” as a leading political priority.

Duff said that he oversaw the hiring of a firm to coordinate health insurance policies across the nine institutions in the IHL system, and that resulted in millions in savings. He also said he helped revamp the interest payments universities were paying on bond projects, resulting in about $100 million in savings.

He appeared at a Mississippi Today event with business leaders about “brain drain” and highlighted the need to keep more Mississippi-educated college students in the state by attracting more private-sector jobs. And in an earlier interview with Mississippi Today, he noted that he and his brother are also major supporters of higher education, having donated about $50 million to Mississippi universities.

Duff also said he supports adding “civic responsibilities” to curricula at Mississippi universities. That reflects ideological currents sweeping the country, with several Republican-led states enacting laws requiring students to take civics-focused courses — often with an emphasis on Western civilization — while scaling back identity-focused content such as race or gender studies.

“I don’t think that’s taught as much anymore. What it means to be an American, a Mississippian. What does it mean to be a future member of society, a citizen? The importance of voting,” Duff said. “Those type of things need to be added into college curricula. Learning our constitution, that type of stuff that makes you more well-rounded and makes you a better student and adult.”

White has called for Mississippi to change how it funds higher education by stripping public money from degree programs that don’t align with the state’s labor force needs. White pitched that policy as his own solution to brain drain. The idea is that outmigration could be blunted by increasing funding for degree programs with higher earning potential right after graduating, such as in engineering or business management, according to a 2023 report issued by White’s office.

White was the earliest and most vocal state leader to come out in favor of banning diversity, equity and inclusion programs in schools.

In a statement, Jacob Walters, a spokesperson for White, said the auditor wants to ensure DEI departments are not recreated again under a different name. White also wants to use the money that previously went to DEI offices to increase campus security.

Walters also provided other higher education proposals White supports, many of which align with the Trump administration’s push to shape teaching around cultural issues and eliminate “useless woke programs.”

“Taxpayer money should not be used to fund Gender Studies programs that feature ‘queer studies’ coursework,” Walters wrote. “This can be found right now at our universities. Instead, taxpayer money should fund degree programs that prepare students for real jobs and don’t saddle them with debt they cannot repay.”

White wants to require that all universities teach “the scientific reality that there are only two sexes,” Walters wrote.

He also supports putting a surcharge on out-of-state students who attend Mississippi universities. The revenue would be used to fund a scholarship for any graduate with good grades in a high-need field who agrees to work in Mississippi for the first four years after graduation.

Duff and White are seen as likely candidates for governor in 2027, but Agriculture Commissioner Andy Gipson is the only notable candidate who has officially announced he’s running.

Gipson also supports eliminating the ability of Mississippi universities to set goals around “diversity outcomes,” a push that became easier after Trump’s reelection, he told Mississippi Today.

“Like most Mississippians, I’ve always supported hiring and recruitment based on individual merit and qualifications, so I was glad to see IHL move this direction beginning in November 2024,” Gipson said.

Going forward, Gipson said Mississippi universities must adapt to a declining student population, which some call an “enrollment cliff.” Mississippi can do that by highlighting its “quality of life and college experience and culture that other parts of the country can’t offer,” he added.

Preparing students with skills in data and artificial intelligence – industries already disrupting the American economy – would also be at the top of the two-term agriculture commissioner’s higher education agenda as governor, he said.

There are just under 80,000 students enrolled at Mississippi’s eight public universities and the University of Mississippi Medical Center, many of whom returned to classes this month. They did so as a legal battle heats up that could fundamentally reshape the composition of student bodies and the dictate which subjects they are taught.

Legal questions loom over DEI

After President Trump made banning DEI programs de rigueur for Republican state legislatures, Mississippi lawmakers introduced legislation for two consecutive legislative sessions. They questioned university officials on their implementation of diversity initiatives and finally succeeded in passing a statewide ban in 2025.

Last week, a federal judge blocked a Mississippi law that bans diversity, equity and inclusion programs in Mississippi public schools from going into effect.

As Mississippi geared up to shutter DEI from its schools, the Trump administration unleashed a torrent of executive actions aimed at universities. The federal government launched civil rights investigations into elite universities and froze billions in federal research money

The Mississippi ruling prevents officials from enforcing the law. Attorneys for the plaintiffs and the state defendants will now move to discovery, where they collect evidence before a bench trial.

The litigation could drag on past the 2026 legislative session, forcing Republican lawmakers to keep pushing to enact a policy they had already spent over a year drafting and debating.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post DEI, campus culture wars spark early battle between likely GOP rivals for governor in Mississippi appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

The content primarily presents a discussion of conservative Republican figures and policies in Mississippi, focusing on debates around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, higher education reform, and cultural issues. It highlights viewpoints aligned with conservative and Republican priorities, such as fiscal responsibility, opposition to DEI initiatives, and emphasis on workforce-aligned education. While the article maintains a factual tone and includes multiple perspectives, the framing and topics covered reflect a center-right political leaning consistent with mainstream conservative discourse.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi Gulf Coast commemorates two decades since Hurricane Katrina

GULFPORT — A Hurricane Hunter flyby Friday opened the 20th anniversary ceremony of Hurricane Katrina at the Barksdale Pavilion in Gulfport, filled with hundreds of people who each has a story of where they were on Aug. 29, 2005, and how Katrina changed their lives.

It ended about 90 minutes later with the young choir from St. James Catholic Church in Gulfport joining songwriter Steve Azar in an energetic rendition of “One Mississippi,” the state song.

It was as if the ceremony and the many photographs and memories brought out and examined this week ripped off the bandage to the pain of Katrina and the loss of 238 people.

Here are the five most memorable quotes of the day from Gulfport:

“We’re so blessed. We’re so fortunate,” said Gulfport Mayor Hugh Keating, whose home was flooded with 8 feet of water during Katrina. “We survived, and we thrived,” he said of south Mississippi.

He and all the speakers saluted the volunteers who came from across the country and even the world to help with the recovery — “960,000. I had no idea there was that many,” Keating said.

The speaker’s platform, set up where the storm surge rushed in to devastate Gulfport, is close to the Mississippi Aquarium and Island View Casino, which opened since the storm. The State Port of Gulfport was rebuilt and the downtown is revitalized, with a lively restaurant scene and offices.

“We coined a new word after Katrina — ‘slabbed,’” said Haley Barbour, who was governor at the time Katrina struck. From Waveland, where after the devastating storm surge “every structure was destroyed,” he said, to Pascagoula, 80 miles away from the center and still with so many homes lost, “It looked like the hand of God had wiped away the Coast — utter destruction,” he said.

The audience gave Barbour and his wife, Marsha, standing ovations. She was at Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg the day before Katrina and “came down with the troops,” her husband said. She was on the Coast, making sure needs were met, for months.

“We are always better together,” said Tulsi Gabbard, U.S. director of national intelligence, who greeted the crowd with an “Aloha.” Listening to the stories from Katrina on the 20th anniversary reminded her of the fires that destroyed Lahaina on Maui in her native state of Hawaii, she said, when 102 people died and the area was left with total devastation.

We will always remember those lost, she said, “But my hope is that we remain inspired, as we stand here 20 years later, by what came after, and remember the unity that we felt, remember the strength that came from all of us coming together as neighbors, as friends, as colleagues, as Americans, that allowed us to get through these historic disasters.”

“Together, we proved you should never bet against Mississippi,” said Gov. Tate Reeves. At the time, Katrina was five times the size of any natural disaster to hit the United States, he said.

People returned home to find nothing but “steps to nowhere,” every other trace of their home gone. Their churches, schools and offices also were damaged and destroyed.

Sen. Trent Lott and Sen. Thad Cochran fought for federal funds, working with state officials and Gov. Barbour to bring south Mississippi back, he said. “Everyone knew who was in charge, and that was Gov. Barbour,” he said. “He never once wavered. He never once quit.”

If Mississippi only built the Coast back to what it was, the state would have failed, was Barbour’s mantra after Katrina and the vision for south Mississippi today. The priorities initially were homes, jobs and schools, and in the 20 years since, south Mississippi has seen great business growth.

“Hurricane roulette,” is how Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann terms it. “Sooner or later it will be our time,” he said, but Mississippi is better prepared than it was for Katrina. Homes and offices were built back stronger and, “We have money set aside in the state,” he said. Mississippi has $1 billion in the windpool between cash and reinsurance for another major storm that one day will come.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Mississippi Gulf Coast commemorates two decades since Hurricane Katrina appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article presents a respectful and largely positive reflection on the recovery efforts following Hurricane Katrina, highlighting leadership from Republican figures such as former Governor Haley Barbour and current Governor Tate Reeves. The tone emphasizes resilience, unity, and effective governance, with no overt criticism of political actors or policies. The inclusion of Tulsi Gabbard, a figure with a complex political background, is framed in a unifying and nonpartisan manner. Overall, the content leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by focusing on conservative leadership and state-led recovery success without engaging in partisan debate.

Mississippi Today

Two Mississippi media companies appeal Supreme Court ruling on sealed court files

A three-judge panel of the Mississippi Supreme Court has ruled that court records in a politically charged business dispute will remain confidential, even though courts are supposed to be open to the public.

The panel, comprised of Justice Josiah Coleman, Justice James Maxwell and Justice Robert Chamberlin, denied a request from Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald that sought to force Chancery Judge Neil Harris to unseal court records in a Jackson County Chancery Court case or conduct a hearing on unsealing the court records.

The Supreme Court panel did not address whether Harris erred by sealing court records and it has not forced the judge to comply with the court’s prior landmark decisions detailing how judges are allowed to seal court records in extraordinary circumstances.

The case in question has drawn a great deal of public interest. The lawsuit seeks to dissolve a company called Securix Mississippi LLC that used traffic cameras to ticket uninsured motorists in numerous cities in the state.

The uninsured motorist venture has since been disbanded and is the subject of two federal lawsuits, neither of which are under seal. In one federal case, an attorney said the chancery court file was sealed to protect the political reputations of the people involved.

READ MORE: Private business ticketed uninsured Mississippi vehicle owners. Then the program blew up.

Quinton Dickerson and Josh Gregory, two of the leaders of QJR, are the owners of Frontier Strategies. Frontier is a consulting firm that has advised numerous elected officials, including four sitting Supreme Court justices. The three justices who considered the media’s motion for relief were not clients of Frontier.

The two news outlets on Thursday filed a motion asking the Supreme Court for a rehearing.

Courts are open to public

In their motion for a rehearing, the media companies are asking that the Supreme Court send the case back to chancery court, where Harris should be required to give notice and hold a hearing to discuss unsealing the remaining court files.

Courts and court files are supposed to be open and accessible to the public. The Supreme Court has, since 1990, followed a ruling that lays out a procedure judges are supposed to follow before closing any part of a court file. The judge is supposed to give 24 hours notice, then hold a hearing that gives the public, including the media, an opportunity to object.

At the hearing, the judge must consider alternatives to closure and state any reasons for sealing records.

Instead, Harris closed the court record without explanation the same day the case was filed in September 2024. In June, Harris denied a motion from Mississippi Today to unseal the file.

The case, he wrote in his order, is between two private companies. “There are no public entities included as parties,” he wrote, “and there are no public funds at issue. Other than curiosity regarding issues between private parties, there is no public interest involved.”

But that is at least partially incorrect. The case involves Securix Mississippi working with city police departments to ticket uninsured motorists. The Mississippi Department of Public Safety had signed off on the program and was supposed to be receiving a share of the revenue.

Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald then filed for relief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Harris improperly closed the court file without notice and did not conduct a hearing to consider alternatives.

After the media outlets’ appeal to the Supreme Court, Harris ordered some of the records in the case to be unsealed.

But he left an unknown number of exhibits under seal, saying they contain “financial information” and are being held in a folder in the Chancery Clerk’s Office.

File improperly sealed, media argues

The three-judge Supreme Court panel determined the media appeal was no longer relevant because Harris had partially unsealed the court file.

In the news outlets’ appeal for rehearing, they argue that if the Supreme Court does not grant the motion, the state’s highest court would virtually give the press and public no recourse to push back on judges when they question whether court records were improperly sealed.

“The original … sealing of the entire file violated several rights of the public and press … which if not overruled will be capable of repetition yet, evading review,” the motion reads.

The media companies also argue that Harris’ order partially unsealing the chancery court case was not part of the record on appeal and should not have been considered by the Supreme Court. His order to partially unseal the case came 10 days after Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald filed their appeal to the Supreme Court.

READ MORE: Judge holds secret hearing in business fight over uninsured motorist enforcement

Charlie Mitchell, a lawyer and former newspaper editor who has taught media law at the University of Mississippi for years, called Judge Harris’ initial order keeping the case sealed “illogical.” He said the judge’s second order partially unsealing the case appears “much closer” to meeting the court’s standard for keeping records sealed, but the judge could still be more specific and transparent in his orders.

Instead of simply labeling the sealed records as “financial information,” Mitchell said the Supreme Court could promote transparency in the judiciary by ordering Harris to conduct a hearing — something he should have done from the outset — or redact portions of the exhibits.

“Closing a record or court matter as the preference of the parties is never — repeat never — appropriate,” Mitchell said. “It sounds harsh, but if parties don’t want the public to know about their disputes, they should resolve their differences, as most do, without filing anything in a state or federal court.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Two Mississippi media companies appeal Supreme Court ruling on sealed court files appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content focuses on transparency, accountability, and the public’s right to access court records, which aligns with values often emphasized by center-left perspectives. It critiques the sealing of court documents and advocates for media and public oversight of judicial processes, reflecting a concern for government openness and checks on power. However, the article maintains a factual tone without overt political partisanship, situating it slightly left of center due to its emphasis on transparency and media rights.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Racism Wrapped in Rural Warmth

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Child in north Alabama has measles, says Alabama Department of Public Health

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

After the Winds: Kindness in Katrina’s Wake

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Southwest Airlines is changing its seating policy for larger customers

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

‘This is what we all work for’: Longest term foster child in Arkansas adopted

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Fever Five: Top highlights from Friday night’s high school football games (Week 1: Jamboree Edition)

-

Mississippi Today1 day ago

DEI, campus culture wars spark early battle between likely GOP rivals for governor in Mississippi

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

Environmental advocates file petition for rehearing in Glynn County wetlands case