Mississippi Today

In the Mississippi Bible Belt, a family wrestles with raising trans kids in the Mormon church

This article was copublished with The 19th, a nonprofit newsroom covering gender, politics, and policy. Sign up for The 19th’s newsletter here.

Marie and Brian Bauman held hands as they walked into the quiet worship hall of a north Mississippi church and situated themselves in the front row. Five of their seven kids settled on either side of them.

Most of the few dozen, mostly white, congregants of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints were dressed for a typical Sunday. The women wore dresses and skirts; the men, collared shirts and ties. But one member of the Baumans stood out: Jack, who wore pants, a tuxedo shirt dotted with silver lightning bolts and a lilac tie. Black nail polish was chipping off of his fingernails.

Ever since he could talk, Jack stated he was a boy. He invented new names for himself — first to use at home, then at school and church. Now 11 years old, Jack is one of a few thousand transgender or gender-nonconforming children in Mississippi growing up in a time when state lawmakers are increasingly hostile toward them.

That Sunday in February marked 40 days since House Republicans passed House Bill 1125 to ban transgender youth in Mississippi from receiving gender-affirming care, which lawmakers repeatedly likened to child abuse and a violation of God’s will, despite every major medical association supporting the treatment. Gov. Tate Reeves would soon make it law, a decision supported by many, but not all, in the Baumans’ largely conservative congregation.

The impending ban made the Baumans fearful for Jack’s health, safety and well-being. It also stirred up painful memories of the time in 2020 when their eldest daughter, Aria, came out as trans as a young adult, only to be told by church leaders that she’d be removed if she wore a dress to church again.

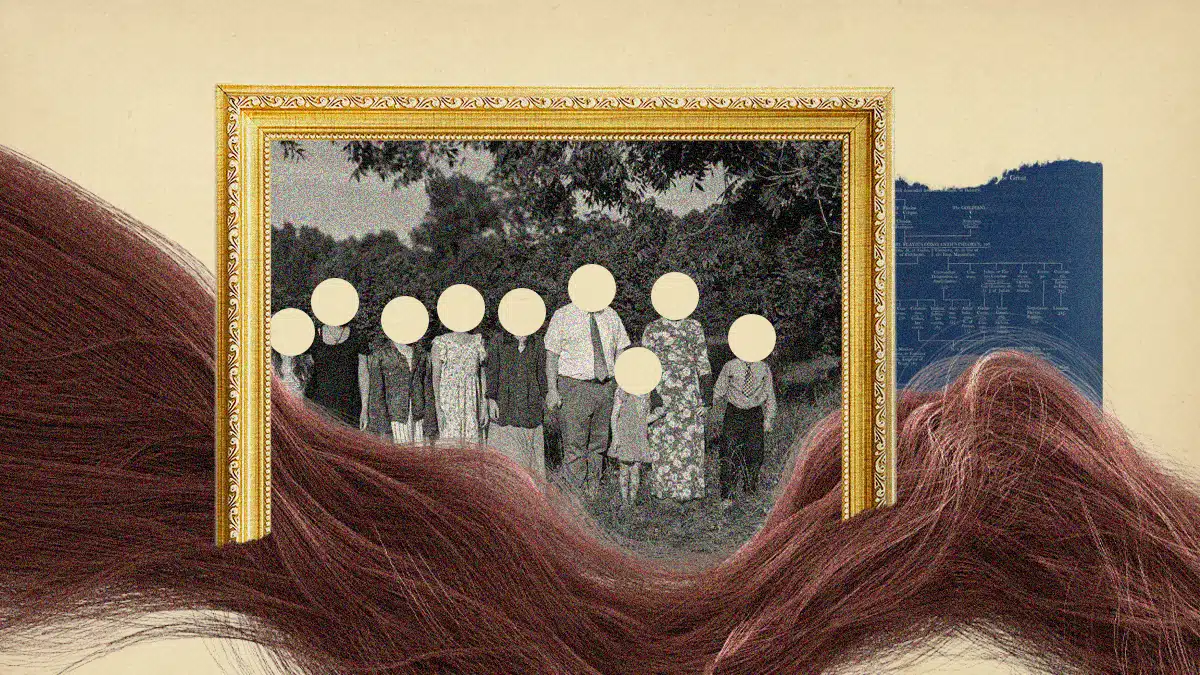

Ever since then, this family, whose names have been changed to protect them from retaliation, has grappled with a contradiction underscored by the surge of anti-trans bills in America: whether it’s possible to raise trans kids in a faith with a strict binary view of gender. Marie and Brian are choosing this path, but many religious families are not.

The family bowed their heads as an elderly member of the church, referred to as a brother, began speaking at the lectern. He is perceived by the family as one of the more accepting members of the congregation, sometimes sending the kids Cow Tales and other candy, but his speech quickly turned into a righteous counsel.

“We see evil crying and carnality covering the earth,” the brother said. “Liars, thieves, adulterers, homosexuals, murderers scarcely seek to hide their abominations from our view. Iniquity abounds, there is no peace on earth. We see evil forces everywhere uniting to destroy the family, to ridicule morality and decency.”

Jack yawned. Curled over a hymn book, he traced a tiny portrait of Jesus in black ink on a program.

“I want you to know that I love each and every one of you,” the brother said, wrapping up. “I’ve had my trials, we’ve all had trials, but together we can face them, we can deal with them and we can work through them.”

Marie hoped that could be the case for her family. She didn’t know at the time that Aria had all but left the church. Her second-oldest child, who like Aria and Jack is also gender-nonconforming, was inching away, too.

At that moment in the sanctuary, Marie hoped that by staying in the church, she might convince other Mormons to become more accepting.

“We’re taught that we’re in families to learn to be more Christ-like,” she said. “One of our core beliefs is that in the afterlife, we can’t take anything with us but we take our relationships. If my relationship with my kids is bad, how can I take anything with me?”

After worship, it was time for Sunday school. In the Baumans’ church, like other Mormon churches, most classes are sorted by gender.

The men gathered alone in the large hall. Kids rushed out into the hallway, heading to their lessons, and the women followed. But Marie did not go with them. She found it difficult to participate in theological discussions with other congregants after what happened with Aria. She was happiest teaching the kids music, but it wasn’t time for that yet, so she waited on a couch in the hallway. A framed portrait of Jesus Christ hung nearby.

As a Mormon trying to raise gender-nonconforming kids, Marie says she sees contradictions in the church’s teachings.

“There were so many places where the choices that were made were terrible — hey,” she said, interrupting herself as the branch president, one of the leaders who had told Aria she should not wear a dress to church again, stopped to say hello. She continued as he walked away: “I find it difficult that you can say we should love everyone and then get up and say just because you’re trans that makes you inherently evil.”

Still, she holds onto the belief that Mormonism, which prohibits women from serving in ecclesiastical roles, could become accepting of her children. But even she recognizes that she might be doing some mental gymnastics.

“We talk about personal revelation, and I could be wanting to believe things so badly that I really believe that,” she said.

“Personal revelation” is a kind of epiphany in Mormon doctrine. It’s divine intervention, a direct message from God. Like many Mormons, it has played a significant role in the life of Marie and her family. It motivated the family to move from Utah to Mississippi in 2017, joining roughly 22,000 other Mormons in the state, according to the church. A new congregation was starting in the state’s northern Hill County, and the Baumans’ wanted to be in a place they felt needed them.

Living in the Bible Belt was an adjustment for everyone, but especially for Aria. Though Mississippi and Utah have a nearly identical breakdown of registered Democrats to Republicans, the Baumans’ new town was tiny, with more Baptist churches than restaurants. It felt more conservative than the Utah college town Aria had left behind.

Growing up, Aria remembers feeling uneasy any time she heard about LGBTQ+ issues in the church, like when LDS leadership campaigned against marriage equality or instituted policies calling on Mormon children to renounce their gay parents. It wasn’t until Aria made queer friends in school, right before the family left Utah, that she understood why these issues bothered her — and started to consider coming out as trans.

But during that 2017 summer in rural Mississippi, more than 1,500 miles away from those friends, there was a discussion between congregants at her new church that triggered Aria. She recalled it was “about how awful everything was because the world was getting more progressive and queer people were becoming more acceptable.”

After the discussion, she ran out into the parking lot hyperventilating. She knew it would probably be safe to tell Marie, who had followed her, why she was so upset — Jack had already come out by then. But she couldn’t bring herself to.

“It was scary,” Aria said. “It affirmed coming out was not safe.”

The family’s move coincided with Donald Trump’s presidency and a nationwide rise in anti-trans bills and policies targeting bathrooms, sports teams, libraries and the classroom. Marie followed these bills closely and joined support groups for trans Mormons and their loved ones. She was looking for ways to advocate for Jack, motivated by family lore of relatives who were suffragettes.

“We are always dragging the church behind the culture,” she said.

By the time the legislative session started this past January, Marie was invested. She joined a Zoom call with other parents of trans kids in Mississippi and learned that lawmakers had already introduced at least 31 bills targeting the LGBTQ+ community. Many of these were inspired by model legislation from right-wing Christian groups like the Alliance Defending Freedom, which has argued that “when culture refuses to acknowledge the fundamental truth that we are created male and female in the image of God, everyone loses.”

Marie observed that outside of a handful of parents and activists, few in Mississippi were advocating for the trans community. At a protest in mid-February, a couple of progressive faith leaders spoke out against the bill.

But they weren’t represented by any lawmaker who has the power to pass legislation inside the Capitol. Republicans, who maintain a supermajority, fell in line to back HB 1125 when it was introduced. Gov. Reeves had signaled it was a priority during his yearly State of the State address. The Democrats’ then-presumptive nominee for governor, Brandon Presley, remained silent about the bill. And when Democratic lawmakers did ask questions about the bill, they repeatedly failed to call out the inaccurate information about gender-affirming care that Republicans gave in response.

“We’re talking about the total and complete removal of parts that God gave you and trying to reverse that,” one of the bill’s handlers, Sen. Joey Fillingane, said during a Senate committee hearing.

In the classroom that Sunday in February, as another mom helped Marie set up folding chairs in preparation for the music lesson, they talked about HB 1125 and how it could affect Jack.

Marie has been thinking about trans issues since Jack was a little kid. She decided years ago that she would be open about her family with anyone who asked, a philosophy that stemmed from a quote she’d read from a motivational speaker: “It’s hard to hate up close.” But she also understands that for many people, especially other members of her congregation, this is new. The common talking points from politicians about parents “coaching” their parents to be trans — comments that infuriate her — can stick with people.

HB 1125 wasn’t a problem for Jack yet, Marie explained to the other mom. Jack’s “social transition” was flexible, meaning that sometimes he went by he/him pronouns and wore masculine clothes, and sometimes he didn’t, a decision Marie let him lead. But if puberty started to harm Jack’s mental health, then the law would become a barrier to the care that Marie would seek.

“Jack currently is not on any hormone blockers, but it’s something we’ve talked about if her mental health is affected,” Marie said.

“I can understand how somebody who has no experience with it might say, ‘No, you shouldn’t let kids have these kinds of hormones,’” the mom replied. “I get that because, I mean, I’m a mom.”

“Right,” Marie said.

“But I’ve watched Jack grow up, so it’s not like I can sit here and say she’s coached into that. Like, I see this. So to deny care, like it’s detrimental for her,” the mom trailed off. “It’s complicated.”

Support like that from congregants was new to Marie. Officially, the LDS church’s stance on trans people is outlined in a document called “the General Handbook.” It advises against transitioning and states that trans Mormons who do would likely face “membership restrictions” that range from no longer being allowed to teach a class to being removed from the congregation entirely.

These guidelines can push queer people away from the church. There are many examples of LGBTQ+ Mormons who have been ostracized by their churches or disavowed by family members who’ve decided the religion is not compatible with acceptance. It’s a particular issue for the rising generation of Mormons: For the increasing number of millennials who’ve left, the church’s stance on LGBTQ+ issues was the third biggest reason.

Yet these rules aren’t fixed, and LDS leadership has changed its stance on social issues in the past, often through personal revelation. Notably, that’s how church leaders decided Black people could hold certain leadership positions in the 1970s. It wasn’t until the 1980s, amid a cultural recoil to the feminist movement and a rise in LGBTQ+ activism, that the church leadership started to insist gender was an immutable characteristic, said Taylor Petrey, a professor at Kalamazoo College who has studied the development of Mormon thought on gender and sexuality.

An important backdrop to the leadership’s positions on social issues, Petrey said, is a desire to dilute the religion’s stereotype, gained from the practice of polygamy, as sexually deviant.

The church often takes “a strong position in favor of a very rigid sexual morality because of that memory of what it meant to be on the outside of American sexual norms,” he said. “They cling very closely to heterosexuality, to patriarchy, to a kind of white, heteronormative family as the new image of sexuality that the church wants to promote.”

Strategy has also played a role in the changing norms. In 2008, the church famously backed California’s Proposition 8, a referendum that banned same-sex marriage. Leadership at the highest levels urged members to vote for it; according to some estimates, members spent more than $20 million in support.

The backlash was fierce. There were protests outside Mormon temples across the country; a popular gay rights blogger called for tourists to boycott skiing in Utah. The church backtracked and, a few years later, supported an anti-discrimination law in Utah, with some religious carve-outs, that protected LGBTQ+ people. Then last year, the church went further, backing a bill in Congress to protect same-sex marriage.

Petrey added that the General Handbook is not compulsory; congregations can deviate from it based on their members’ needs and expectations.

“Family unity, family, love, family harmony are such prioritized values that when the church or society is seen as causing a rift or is potentially a source of pain, many Latter Day Saints are like, ‘Well, I’ve been taught all my life that the family is the most important thing,’” Petrey said. “‘I’m going to choose my family.’”

That thinking is one reason why Aria stayed in the church despite feeling increasingly wary. Aria also knew that if she came out, she would risk severing her ties to her family, possibly forever. In Mormon doctrine, families stay together in the afterlife, as long as they’ve remained in the church in good standing.

By the time she was gearing up in 2020 for her mission, a rite-of-passage for Mormons that involves volunteer service or proselytizing, Aria knew she was trans. But she hadn’t come out yet, even as she was growing away from the church. A conversation with a family member who left the church inspired her to explore other forms of spirituality like paganism; its dramatic nature was attractive to her as a former theater kid. In Mississippi, she got close to a non-denominational pastor. She told him she was trans and, right after, he assaulted her.

“I kind of just went back deep in the closet,” she said.

Her mission loomed. It came with some added pressure: Aria and her parents thought she would be the first Mormon from north Mississippi to go on a mission since the late 1980s and possibly the first ever from the area to complete one. Her understanding was that a woman who went before her died before she could finish.

She had to prepare for it. Missionaries are expected to keep their hair cropped, but Aria’s hair was long and curly, so she burned locks of it in the woods. She tied herself blindfolded to a stake outside the family’s home, a ritual she said was meant to create a division in her life between her mission and “everything else.”

But the night before she was set to get on the plane to the Pacific Northwest, she broke down and told Marie that she was trans. Marie encouraged her to try to do the mission anyway.

“There is nothing you’ve said that makes you unworthy to serve,” Marie said she told Aria.

So Aria went. Away from home, her antidepressants stopped working. Her panic attacks became more frequent. Soon, it all became too much to wear the elder’s uniform of pants, a white button-up and a tie. She could no longer pretend like everything was OK. She made plans for suicide. But before that, Aria talked to a church therapist who helped her get a plane ticket home.

In the weeks that followed, Aria came out to her dad via letters, because that was easier than speaking the words. That October, she told her sister Sabrina, who is now 8 years old, when they were quarantined together after a COVID exposure in the bedroom they shared. She was touched when Sabrina suggested they both wear dresses to church that Sunday.

Sabrina wasn’t called to church that day — during the pandemic, congregants who were not needed stayed home — but Aria was asked to teach a primary class. So she donned a sage green wrap dress patterned with white flowers. She didn’t think it would be an issue because a few nights earlier, she’d worn a feminine vampire costume to a church Halloween party.

At service, only one person said something to her: A kid in her primary class asked why she was wearing a dress. She asked him why he wasn’t.

But a few days later, the branch president invited Aria to his house. Another leader was there. They told her she had been disruptive and warned that if she wore a dress again, she would be “exported out,” meaning removed from the church. She would be welcome back if she wore a pantsuit, the branch president said.

Aria left in tears.

The next week, church was awkward for Marie and Brian. Even though no one said anything to them about Aria, it felt like everyone knew what had happened.

“There was this weird thing, like almost a pity,” Marie said of the aftermath at church. “Like, ‘I’m sorry your child is doing this.’ And I just kept thinking, ‘I don’t feel bad about this. I feel bad that you feel bad about this.’”

On the way home in their golden minivan, the family went over what they had learned that day at church that day in February. The three teenagers had just watched a YouTube video, well-known to many Mormons, about a bespectacled housewife who judges her neighbor’s dirty clothesline. One day, she is astonished — her neighbor’s laundry is clean. Then her husband informs her that actually, she had been looking at the woman’s home through her own dirty kitchen windows. He had washed them.

The video ends with a lesson from the LDS president who notes, “thus the commandment, ‘judge not.’”

At home, Jack and Sabrina pulled on rain boots and ran around the family’s hilly property, the family’s older rescue dog bounding after them. They showed off the chicken coops, their goats with Russian names and a tree that Jack called “Whomping Willow,” but the priority was looking at the hogs. The babies had been castrated the day before, their tails still limp from the alcohol. The parents were plopped in the mud.

“You can tell which one is a girl, because the girl has,” Jack paused. “You’re going to have to explain this, Sabrina. I don’t want to say it out loud.”

“What?” Sabrina asked. “Both of them have nipples.”

“But hers are bigger,” Jack said.

Out of all seven children, Jack and Sabrina had spent the bulk of their childhood in Mississippi. At school, Jack was sometimes called by the name Marie and Brian gave him, sometimes by the one he chose; it depended on the teacher. The routine he has adopted — switching between pronouns — was growing uncomfortable, he said.

“I don’t know, I mean, I was born a girl but I want to be a boy,” Jack said.

“Jack is a girl at school and a boy at home,” Sabrina said.

“It’s weird,” Jack said. He announced the tour was over.

As Brian prepped chicken soup for dinner, Marie sat on the family’s velvet green couch and scrolled through her phone, searching for her favorite family photo. It shows the family standing hand-in-hand, eyes squinting in the bright sun, surrounded by dense, green vines. Aria is wearing the same dress she wore to church and fingerless, black-and-gray striped gloves.

Ever since the incident with church leaders, Marie said, Aria had been drifting away from the church. She tried attending service at a congregation in Tennessee, but the hour-long drive was tiring. The branch president came to the family’s house to try to apologize, but Aria had a panic attack. As he talked to Marie, Aria sat on the porch until she was finally calm enough to meet with him.

By fall 2021, she decided to move back to Utah to be closer to her queer friends and to try college again at a state university. In civics class one day, Aria listened to a conversation about how much money church leadership had poured into opposing same-sex marriage in California. It struck her that this wasn’t just the actions of people like her mom or other church congregants; who are, in Aria’s view, “apologetics” who don’t know better. The church’s support of Proposition 8 was an organized campaign to oppose her rights and the rights of people like her, Aria said. Still, it hurt to realize that her parents supported that campaign through tithings.

She had a revelation: “It finally hit me that it couldn’t be true, that it couldn’t be for me, that I was never going to fit within Christianity.”

“I came to the conclusion that either the church was wrong in every way, and I shouldn’t be associated with it, or the church was right and if that’s the case, then God hates me anyway so I might as well leave,” she said.

All this led Aria to tell Marie in mid-February that she was considering having her name purged from church records, a step that would completely sever her relationship with Mormonism. In March, she made it official.

Marie said she knew she could not dissuade Aria. She cites the varying viewpoints of congregants like the brother, or even the branch president. And she understands why Aria thinks it’s hypocritical of her to pay tithings to the church even as she disagrees with its stance on LGBTQ+ issues.

But, she said, she’s not responsible for how the church spends its money.

“I’m not going to be held responsible for that in the afterlife, whoever is mishandling it now — it is on them,” she said.

If Aria can’t be part of the church, Marie said she understands. Mormons are more conservative, and she said that often, the church’s culture is misunderstood as a substitute for doctrine.

“I may have issues with church policy but that doesn’t change my faith in the doctrine,” Marie said. “I don’t want to be doing mental gymnastics, and I hope that’s not what I’m doing. I do make a distinction between the church as an institution and the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

As for Jack, Marie said she and her husband haven’t told him about the bill yet, to avoid causing undue anxiety or make him feel like a path forward is foreclosed as long as they live in Mississippi.

As Marie talked, Jack and his siblings passed around a piece of paper, playing a game in which each person contributes a sentence to a short story. Jack handed the final result — a story about an animal that is ostracized by its family but ultimately finds a way to survive. Was it about them?

Jack grinned. “Maybe.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Brain drain: Mother understands her daughters’ decisions to leave Mississippi

Editor’s note: This Mississippi Today Ideas essay is published as part of our Brain Drain project, which seeks answers to Mississippi’s brain drain problem. To read more about the project, click here.

Back when I was a kid in 1988, my mama and I had an argument about what I wanted to major in at college.

I had dreamed of being a journalist since the age of 8. To me, that meant that I was going to Ole Miss, which had the journalism department.

My mama said I could only go away from home to Ole Miss if I was going to major in law.

So I settled on going to Mississippi State University just down the road and majoring in communication. She told me I should major in engineering since that’s what State was known for.

I said, “That’s even dumber than me going to law school. I hate math.”

“Well, you could at least try,” she said.

I said no. Then she told me I was wasting my education and turned her back on me.

I get it. She knew and I knew that I couldn’t stay in Choctaw County where I was raised and earn a living with that degree. I would have to go somewhere else — probably to the Jackson metro area and work for Gannett or the Associated Press. Or to Memphis. Or Biloxi. Or even New Orleans. She never really forgave me for moving to the Jackson metro, working in my field and raising her grandchildren so far from her.

After a while, I got used to the pace of life around here. I knew I probably wouldn’t ever move anywhere else because I noticed that people who left Mississippi often came back, whether due to family obligations or a realization that “somewhere else” wasn’t quite all it was cracked up to be.

I also noticed that a lot of people played up how they were from Mississippi while making a very good living being someplace else. I decided I wanted to prove you could be from Mississippi, live in Mississippi, work in Mississippi and make something of yourself without leaving Mississippi.

But I noticed something else over the years, too. Most of the kids in Brandon dreamed of going off from home to cities like Atlanta, Nashville, Dallas, DC, New York or Orlando. They didn’t seem to have reasons — just a desire to get away from the state as fast as they could.

Then my three daughters and I started having conversations about what they wanted to major in when they went to college. My oldest wanted to be a chef. My middle one was undecided between chemical engineering and landscape architecture. And my youngest was fascinated with roads and bridges.

I was all too aware of what had happened in the job markets in Mississippi since I had come up. Companies closed operations in a globalized economy and fled to cheaper labor markets. The advent of the internet meant employers could hire from all over the world. Longtime business leaders retired and sold out to big corporations that reduced investments in local communities that had supported those businesses for decades and then complained that those towns didn’t offer enough amenities for their employees to want to relocate there.

But the reality really set in when my chef daughter chose her first internship — in historic Williamsburg, Virginia.

I would never have dreamed of driving that far from home to try out a place to work when I was her age. Then after her senior year, she interned at Walt Disney World and got hired full-time before the internship was over. She was off to live in Orlando where now with her husband and young son she’s creating community and loves going to work every day with a pretty enviable benefits package, too, a thing unheard of in the culinary world in Mississippi.

My middle one finally settled on chemical engineering and was picked for a co-op job in her first semester at age 18 at a company in Georgia. When she graduated four years later, we packed her off to Indiana for a research and development job, and she now lives in New Hampshire with her husband, making six figures a year at 26 years old and looking forward to partaking in the cultural offerings in New York City when she can.

The youngest is currently in college for civil engineering, and I’m bracing myself for the inevitable. She doesn’t want to work for state government, so she’s likely going out of state as well. Her comment about coming back to Jackson metro was the most damning of all. “There’s nothing to do here,” she says.

A lot of people ask me questions: How often do you see your daughters? How can you stand being so far from your grandson? Don’t they at least come home for Christmas?

The answer to all of those questions is that we do the best we can. We text, we message on Facebook, we talk on the phone at least once a week, every Sunday. We arrange visits; sometimes it’s us driving to them while other times they drive to us.

I can’t imagine making my children as miserable as my mom made me over my life choices. We are flexible, understanding, and very, very proud of our daughters, who are grappling with enough in their lives without us loading them down with guilt over when they are coming home.

The calculus may change in the future. We may have declines in health and need to move closer to one of our children if we need assistance. Or we may need to be in assisted living care here in Mississippi where such care may be marginally cheaper than wherever our girls land.

But I don’t wish our girls had settled for life in Mississippi.

What I wish is that Mississippi could find a way to live up to its potential — to be a place more worthy of my daughters’ loyalty, affections and investment in themselves.

Maybe it will be someday. I hope so, for all of our sakes.

Julie Liddell Whitehead lives and writes from Mississippi. An award-winning freelance writer, Julie covered disasters from 9/11 to Hurricane Katrina throughout her career. Her first book is “Hurricane Baby: Stories,” published by Madville Publishing. She writes on mental health, mental health education and mental health advocacy. She has a bachelor’s degree in communication, with a journalism emphasis, and a master’s degree in English, both from Mississippi State University. In 2021, she completed her MFA from Mississippi University for Women.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Brain drain: Mother understands her daughters' decisions to leave Mississippi appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This essay reflects a Center-Left perspective by focusing on social and economic challenges faced by Mississippi, such as brain drain, job market changes, and community decline. The tone is empathetic and advocates for investment in local opportunities and amenities to retain talent, aligning with progressive concerns about economic inequality and regional development. However, it remains largely personal and reflective rather than explicitly ideological or partisan. The article critiques systemic economic shifts without advancing a polarized political agenda, emphasizing hope for future improvement and a more supportive environment for young professionals.

Mississippi Today

After 30 years in prison, Mississippi woman dies from cancer she says was preventable

Behind Bars, Beyond Care:

A Mississippi Today investigation into suffering, secrecy and the business of prison health care

Susie Balfour, diagnosed with terminal breast cancer two weeks before her release from prison, has died from the disease she alleged past and present prison health care providers failed to catch until it was too late.

The 64-year-old left the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in December 2021 after more than 30 years of incarceration. She died on Friday, a representative for her family confirmed.

Balfour is survived by family members and friends. News of her passing has led to an outpouring of condolences of support shared online from community members, including some she met in prison.

Instead of getting the chance to rebuild her life, Balfour was released with a death sentence, said Pauline Rogers, executive director of the RECH Foundation.

“Susie didn’t just survive prison, she came out fighting,” Rogers said in a statement. “She spent her final years demanding justice, not just for herself, but for the women still inside. She knew her time was limited, but her courage was limitless.”

Last year, Balfour filed a federal lawsuit against three private medical contractors for the prison system, alleging medical neglect. The lawsuit highlighted how she and other incarcerated women came into contact with raw industrial chemicals during cleaning duty. Some of the chemicals have been linked to an increased risk of cancer in some studies.

The companies contracted to provide health care to prisoners at the facility over the course of Balfour’s sentence — Wexford Health Sources, Centurion Health and VitalCore, the current medical provider — delayed or failed to schedule follow-up cancer screenings for Balfour even though they had been recommended by prison physicians, the lawsuit says.

“I just want everybody to be held accountable,” Balfour said of her lawsuit. “ … and I just want justice for myself and other ladies and men in there who are dealing with the same situation I am dealing with.”

Rep. Becky Currie, who chairs the House Corrections Committee, spoke to Balfour last week, just days before her death. Until the very end, Balfour was focused on ensuring her story would outlive her, that it would drive reforms protecting others from suffering the same fate, Currie said.

“She wanted to talk to me on her deathbed. She could hardly speak, but she wanted to make sure nobody goes through what she went through,” Currie said. “I told her she would be in a better place soon, and I told her I would do my best to make sure nobody else goes through this.”

During Mississippi’s 2025 legislative session, Balfour’s story inspired Rep. Justis Gibbs, a Democrat from Jackson, to introduce legislation requiring state prisons to provide inmates on work assignments with protective gear.

Gibbs said over 10 other Mississippi inmates have come down with cancer or become seriously ill after they were exposed to chemicals while on work assignments. In a statement on Monday, Gibbs said the bill was a critical step toward showing that Mississippi does not tolerate human rights abuses.

“It is sad to hear of multiple incarcerated individuals passing away this summer due to continued exposure of harsh chemicals,” Gibbs said. “We worked very hard last session to get this bill past the finish line. I am appreciative of Speaker Jason White and the House Corrections Committee for understanding how vital this bill is and passing it out of committee. Every one of my house colleagues voted yes. We cannot allow politics between chambers on unrelated matters to stop the passage of good common-sense legislation.”

The bill passed the House in a bipartisan vote before dying in the Senate. Currie told Mississippi Today on Monday that she plans on marshalling the bill through the House again next session.

Currie, a Republican from Brookhaven, said Balfour’s case shows that prison medical contractors don’t have strong enough incentives to offer preventive care or treat illnesses like cancer.

In response to an ongoing Mississippi Today investigation into prison health care and in comments on the House floor, Currie has said prisoners are sometimes denied life saving treatments. A high-ranking former corrections official also came forward and told the news outlet that Mississippi’s prison system is rife with medical neglect and mismanagement.

Mississippi Today also obtained text messages between current and former corrections department officials showing that the same year the state agreed to pay VitalCore $100 million in taxpayer funds to provide healthcare to people incarcerated in Mississippi prisons, a top official at the Department remarked that the company “sucks.”

Balfour was first convicted of murdering a police officer during a robbery in north Mississippi, and she was sentenced to death. The Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the conviction in 1992, finding that her constitutional rights were violated in trial. She reached a plea agreement for a lesser charge, her attorney said.

As of Monday, the lawsuit remains active, according to court records. Late last year Balfour’s attorneys asked for her to be able to give a deposition with the intent of preserving her testimony. She was scheduled to give one in Southaven in March.

Rogers said Balfour’s death is a tragic reminder of systemic failures in the prison system where routine medical care is denied, their labor is exploited and too many who are released die from conditions that went untreated while they were in state custody.

Her legacy is one RECH Foundation will honor by continuing to fight for justice, dignity and systemic reform, said Rogers, who was formerly incarcerated herself.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post After 30 years in prison, Mississippi woman dies from cancer she says was preventable appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical view of the Mississippi prison health care system, highlighting systemic failures and medical neglect that led to the death of a formerly incarcerated woman. The tone and framing focus on social justice issues, prisoner rights, and the need for government accountability and reform, which align with Center-Left values emphasizing government responsibility for vulnerable populations. While the article is largely investigative and fact-based, its emphasis on advocacy for reform, criticism of privatized prison health contractors, and highlighting bipartisan legislative efforts suggest a Center-Left leaning perspective rather than neutral reporting.

Mississippi Today

FBI concocted a bribery scheme that wasn’t, ex-interim Hinds sheriff says in appeal

Former interim Hinds County sheriff Marshand Crisler is appealing bribery and ammunition charges stemming from his 2021 campaign, arguing that the federal government played on his relationship with a former supporter to entrap him.

Crisler had asked Tonarri Moore, who donated to past campaigns, for a financial contribution for the sheriff’s race. Moore said he would donate if Crisler helped with several requests. Without the previous relationship, Crisler would not have acted, his attorney argues, and Crisler had no reason to believe he was being bribed.

“The government, having concocted a bribery scheme to entrap Crisler, then had to contrive a corresponding quid pro quo to support the scenario with which to entrap him,” attorney John Holliman wrote in a Saturday appellant brief.

Crisler is asking the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals to reverse his conviction and render its own rulings on both counts.

He was convicted in federal court in November after a three-day trial and sentenced earlier this year to 2 ½ years in prison. Crisler is serving time in FCI Beckley in West Virginia.

The day before Crisler reached out to Moore to ask for support for his campaign for sheriff, Drug and Enforcement Administration agents raided Moore’s home and found guns and drugs. An FBI agent called to the scene looked through Moore’s phone and saw Crisler had called.

According to the appellant brief, the agent asked Moore what Crisler would do if offered money, and if Moore was bribing him. Moore said he wasn’t bribing Crisler, and the agent asked if Moore would do it.

At that time, there weren’t reasonable grounds to start a bribery investigation into Crisler, his attorney argues, nor was there reason to believe he was seeking a bribe.

Moore agreed to become an informant for the FBI, in exchange for the government not prosecuting him for the guns and drugs.

The FBI fitted him with a wire to record Crisler during meetings, which began that day. The meetings included one inside Moore’s night club and a cigarette lounge in Jackson. Agents provided Moore with the $9,500 he gave to Crisler between September and November 2021.

Crisler’s 2023 indictment came as he campaigned again for sheriff and months before the primary election. He remained in the race and lost to the incumbent who he faced in 2021.

At trial, the government argued the exchange of money were attempts to bribe because Moore made several requests of Crisler: to move his cousin to a different part of the Hinds County Detention Center, to get him a job in the sheriff’s office and for Crisler to let Moore know if law enforcement was looking into his activities.

In closing arguments, Assistant U.S. Attorney Charles Kirkham pointed to examples of quid pro quo in recordings, including one where Moore said to Crisler, “You scratch my back, I scratch yours” and Crisler replied “Hello!” in a tone that the government saw as agreement.

The appellant’s brief argues that without Moore’s requests, the government lacked a way to show quid pro quo, a requirement of bribery charge: that Crisler committed or agreed to commit an official act in exchange for funds.

Moore also asked Crisler to give him bullets despite being a convicted felon, which is prohibited under federal law. The brief notes how the government directed Moore to come up with a story for needing the bullets and to ask Crisler to give them to him.

In response, Crisler told Moore he could buy bullets at several sporting goods stores. Moore said they ran out, and eventually Crisler gave him bullets.

Crisler also argues that the government prosecuted routine political behavior. Specifically, accepting campaign donations is not illegal, and can not constitute bribery unless there is an explicit promise to perform or not perform an official act in exchange for money.

“Our political system relies on interactions between citizens and politicians with requests being made for this or that which is within the power of the elected official to do,” the brief states. “This does not constitute a bribery scheme. It is the normal working of our political system.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post FBI concocted a bribery scheme that wasn’t, ex-interim Hinds sheriff says in appeal appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

The article presents the legal appeal of former interim Hinds County sheriff Marshand Crisler with a focus on his argument that the FBI orchestrated an entrapment scheme. The language is largely factual and centers on the defense’s claims and legal standards for bribery, emphasizing normal political behavior versus illegal conduct. While the article reports on the government’s position, it gives significant space to Crisler’s defense and critiques of federal prosecution tactics. This framing, highlighting skepticism toward federal law enforcement and emphasizing the defense perspective, suggests a slight center-right leaning, reflecting a cautious stance on government overreach without overt ideological language.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Rural Texas uses THC for health and economy

-

Mississippi Today3 days ago

After 30 years in prison, Mississippi woman dies from cancer she says was preventable

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Decision to unfreeze migrant education money comes too late for some kids

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed4 days ago

Woman charged after boy in state’s custody dies in hot car

-

Mississippi Today7 days ago

They own the house. Why won’t they cut the grass?

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

Trump’s big proposed cuts to health and education spending rebuffed by US Senate panel

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

Delta jet makes emergency landing | FOX 5 News

-

Mississippi News Video7 days ago

Jones County investigators work to solve 2011 cold case