Jorge Fernández/LightRocket via Getty Images

Eli Elster, University of California, Davis

Of the 8.7 million species on Earth, why are human beings the only one that paints self-portraits, walks on the Moon and worships gods?

For decades, many scholars have argued that the difference stems from our ability to learn from each other. Through techniques such as teaching and imitation, we can create and transmit complicated information over many generations.

So if a human finds, for instance, a better but more complex way to make a knife, they can pass along the new instructions. One of those learners might stumble upon their own improvement and pass it along in turn.

If this loop continues, you get a ratchet effect, in which small changes can accumulate over time to produce increasingly intricate behaviors and technologies. This process produces our uniquely complex cultures: Scientists call it cumulative cultural evolution.

But extensive data has emerged suggesting that other animals, including bees, chimpanzees and crows, can also generate cultural complexity through social learning. Consequently, the debate over human uniqueness is shifting in a new direction.

As an anthropologist, I study a different feature of human culture that researchers are beginning to think about: the diversity of our traditions. Whereas animal cultures affect just a few crucial behaviors, such as courtship and feeding, human cultures cover a massive and constantly expanding set of activities, from clothing to table manners to storytelling.

This new view suggests that human culture is not uniquely cumulative. It is uniquely open-ended.

What is cumulative culture?

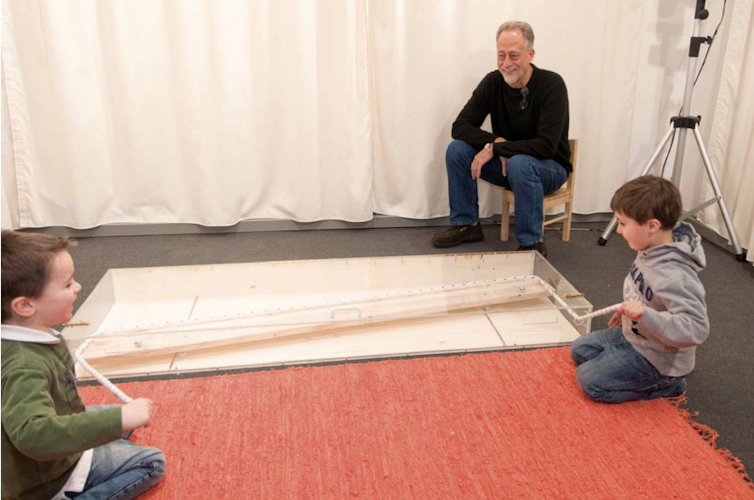

In the early 2000s, a research team led by psychologist Michael Tomasello tested 105 human children, 106 adult chimpanzees and 32 adult orangutans on a battery of cognitive assessments. Their goal was to see whether humans held any innate cognitive advantage over their primate cousins.

Surprisingly, the human children performed better in only one capacity: social learning. Tomasello thus concluded that humans are not “generally smarter.” Rather, “we have a special kind of smarts.” Our advanced social abilities allow us to transmit information by accurately teaching and learning from each other.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Humans’ apparent social learning abilities suggested a clear explanation for our unique cultural traits. Knowledgeable humans – say, someone who discovers a better way to make a spear – can successfully transfer that skill to their peers. But an inventive chimp – one who discovers a better way to smash nuts, for example – can’t successfully share their innovation. Nobody listens to Chimp Einstein. So our inventions persist and build upon each other, while theirs vanish into the jungle floor.

Or so the theory went.

Now, though, scientists have hard evidence showing that, just like us, animals can learn from each other and thus maintain their cultures for long periods of time. Groups of swamp sparrows appear to use the same song syllables for centuries. Meerkat troops settle on different wake-up times and maintain them for a decade or more.

Of course, long-term social learning is not the same as cumulative culture. Yet scientists also now know that humpback whale songs can oscillate in complexity over many generations of learners, that homing pigeons create efficient flight paths by learning from each other and making small improvements, and that hooved mammals cumulatively alter their migration routes to exploit plant growth.

Once again, the animals have shot down our claim to uniqueness, as they have innumerable times throughout scientific history. You might wonder, at this point, if we should just settle the uniqueness question by answering: “We’re not.”

If not cumulative culture, what makes us unique?

But it remains the case that humans and their cultures are quite different from animals and their equivalents. Most scholars agree about that, even if they disagree about the reasons why. Since cumulative complexity appears not to be the most important difference, several researchers are sketching out a new perspective: Human culture is uniquely open-ended.

Currently, anthropologists are discussing open-endedness in two related ways. To get a sense of the first, try counting the number of things you’re engaged with, right now, that came to you through culture. For example, I picked my clothes today based on fashion trends I did not develop; I am writing in a language I did not invent; I tied my shoes using a method my father taught me; there are paintings and postcards and photographs on my walls.

Give me 10 minutes, and I could probably add 100 more items to that list. In fact, other than biological acts such as breathing, it is difficult for me to think of any aspect of what I’m doing right now that is not partially or completely cultural. This breadth is incredibly strange. Why should any organism spend time pursuing such a wide range of goals, particularly if most of them have nothing to do with survival?

Other animals are much more judicious. Their cultural variation and complexity pertains almost entirely to matters of subsistence and reproduction, such as acquiring food and mating. Humans, on the other hand, lip-synch, build space stations and, less grandiosely, have been known to do things such as spend six years trying to park in all 211 spots of a grocery store lot. Our cultural diversity is unparalleled.

Open-endedness, as a unique human quality, is not just about variety; it reflects the quantum leaps by which our cultures can evolve. To illustrate this peculiarity, consider a hypothetical example regarding the rocks that chimpanzees use to smash nuts.

Anup Shah/Stone via Getty Images

Let’s say these chimps would benefit from using rocks that they can swing as hard and accurately as possible, but that they don’t immediately know what kind of rocks those would be. By trying different options and observing each other, they might accumulate knowledge of the best qualities in a nut-smashing rock. Eventually, though, they’d hit a limit in the power and precision available by swinging a rock with your fist.

How could they get past this upper limit? Well, they could tie a stick to their favorite rock; the extra leverage would help them smash the nuts even harder. As far as we know, though, chimpanzees aren’t capable of realizing the benefits of harnessing this additional quality. But we are – people invented hammers.

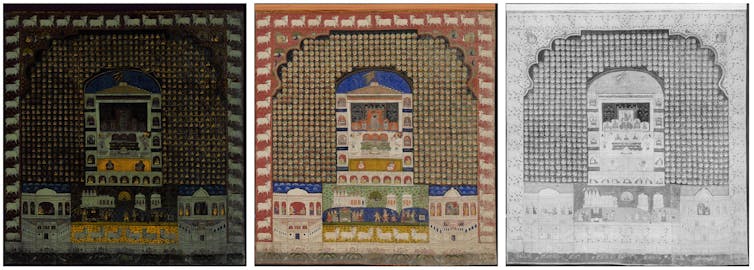

Crucially, discovering the power of leverage allows for more than just better nut-smashing. It opens up innovations in other domains. If adding handles to wielded objects allows for better nut-smashing, then why not better throwing, or cutting, or painting? The space of cultural possibilities, suddenly, has expanded.

Through open-ended cultural evolution, human beings produce open-endedness in culture. In this respect, our species is unparalleled.

What’s next?

Researchers have not yet answered most of the major questions about open-endedness: how to quantify it, how we create it, whether it has any true limitations.

But this new framework must shift the tides of a related debate: whether there is something obviously different about the way human minds work, other than social learning capacities. After all, every cultural trait emerges through interactions between minds – so how do our minds interact to produce such a degree of cultural breadth?

No one knows yet. Interestingly, this shifting debate over how cognition influences culture coincides with a spate of research bridging psychology and anthropology, which explores why certain behaviors – such as singing lullabies, curative bloodletting and storytelling – recur across human cultures.

Human minds produce unparalleled diversity in their cultures; yet it is also true that those cultures tend to express variations on a strict set of themes, such as music and marriage and religion. Ironically, the source of our open-endedness may illuminate not only what makes us so diverse, but also what makes us so often the same.

Eli Elster, Doctoral Candidate in Evolutionary Anthropology, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.