Mississippi Today

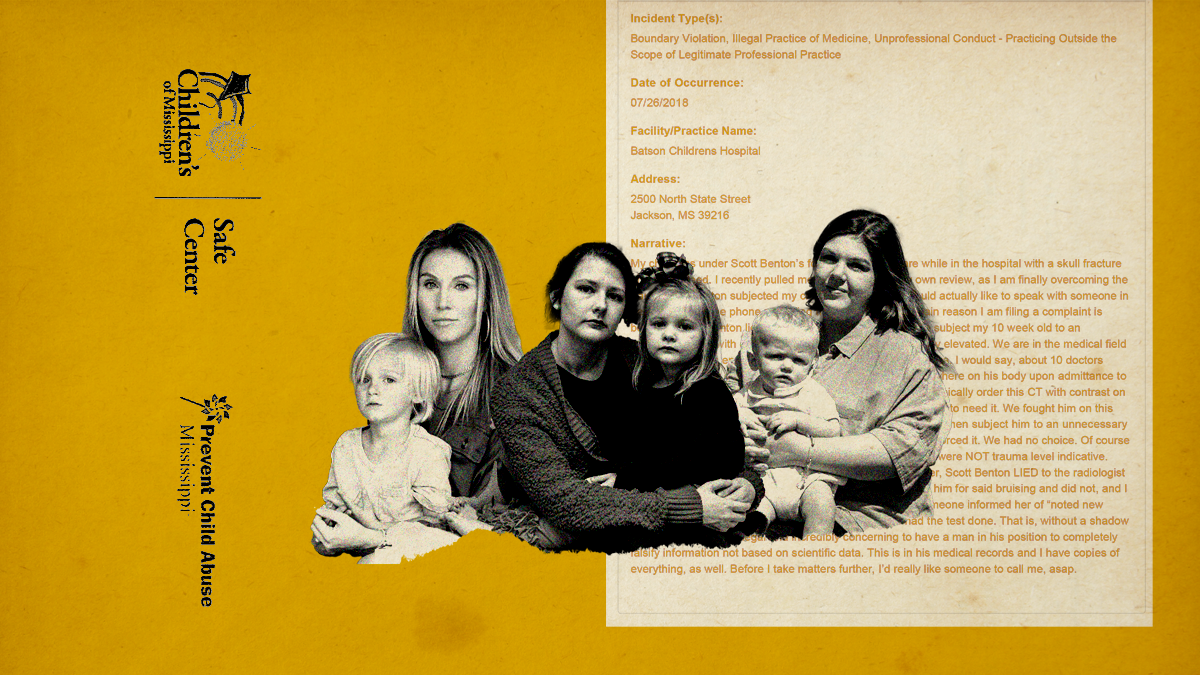

How Dr. Scott Benton’s decisions tore these families apart

How Dr. Scott Benton’s decisions tore these families apart

This story is the third part in Mississippi Today’s “Shaky Science, Fractured Families” investigation about the state’s only child abuse pediatrician crossing the line from medicine into law enforcement and how his decisions can tear families apart.Read the full series here.

Caryn Jordan, Columbia

When Caryn Jordan took her 10-month-old daughter to Forrest General Hospital on March 29, 2020, she never imagined the state would take her child from her.

She said she also never considered that a pediatrician who would accuse her of child abuse wouldn’t do the necessary testing to determine if a genetic disease caused her daughter’s fractures.

The nightmare started when Jordan was putting her daughter Sawyer in her high chair. She noticed one leg was warm and swollen. She tried to get Sawyer to stand up, but the child couldn’t handle pressure being applied to the swollen leg.

At Forrest General Hospital, Jordan said doctors told her an X-ray revealed a fracture on Sawyer’s leg and that the hospital would have to transfer Sawyer to the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) in Jackson because they were not equipped to put a cast on an infant. The hospital had contacted Child Protective Services, she said she later realized.

An official with Forrest General Hospital said when there is suspected abuse or neglect, the hospital social worker is consulted and further screening is done.

“CPS is notified when circumstances warrant,” said Suzanne Wilson, the director of emergency services and transfer center at the hospital.

Wilson said not all suspected abuse cases are transferred out of the facility, but those requiring a specialist’s care are transferred, as well as those in need of pediatric services not provided at the hospital.

After performing a full body X-ray on Sawyer at UMMC, doctors told Jordan her daughter had a broken leg and 11 fractures across her body in various stages of healing.

Jordan was baffled. Sawyer had rarely left their home, aside from frequent doctor visits due to stomach issues and a salmonella infection. Her mind raced for answers.

Then Jordan got a call from Dr. Scott Benton, a pediatrician at UMMC who specializes in child abuse pediatrics. He told her that Sawyer looked like she had been thrown against a wall or in a car accident, she said. Another mother told Mississippi Today that Benton also accused her of throwing her baby against the wall.

“He spoke to me like I was this abusive, disgusting mother,” Jordan said. “I don’t think I’ve ever been that angry.”

Benton, who Jordan said she never saw in person, determined abuse caused her injuries. Jordan said to her knowledge, Benton, who told her on the phone he was out of town at the time, never saw Sawyer in person.

Jordan would not be taking Sawyer home. She was told to leave the hospital, and Sawyer went into the custody of Child Protective Services.

Back home in Columbia, Jordan turned all of her energy into getting Sawyer back, a fight that cost her everything. She was only able to work part time due to frequent court dates and doctor’s visits. She drained her savings and lost her health insurance. Her relationship with her boyfriend imploded. She moved back in with her parents.

“Could the fractures have occurred during birth?” she wondered. At one point, Sawyer got stuck in the birth canal. She had to be pushed back inside and delivered through an emergency cesarean section, Jordan said.

“Might Sawyer have a brittle bone disease called osteogenesis imperfecta?” Jordan thought. The group of inherited genetic disorders affects how the body makes collagen and causes fragile bones. A Facebook group she joined for parents whose children had the disorder encouraged her to request a bone density test.

But when Jordan proposed the idea, Benton replied in text messages that she shared with Mississippi Today: “There is no validated and approved bone density test for infants.”

While bone density tests are not typically performed on infants, there are alternative methods, Jordan said a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital New Orleans told her in June 2020. They include a skin biopsy or genetic testing to look for anomalies in certain genes involved in encoding collagen.

In videos shared with Mississippi Today, the New Orleans doctor tells Jordan that Sawyer’s symptoms and injuries are consistent with what is seen in a child with brittle bone disease, and that often the fractures are painless and left undiscovered for some time.

But Jordan was unaware Benton had performed a genetic osteogenesis imperfecta panel test on Sawyer on March 31, nor was she given the results. That test detected a variant of uncertain significance in her COL1A1 gene, which is involved in collagen production, according to Sawyer’s medical records from UMMC.

Dr. Mahim Jain, director of the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Clinic at Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said issues with the COL1A1 gene are a major cause of OI.

“A variant of uncertain significance doesn’t really say, ‘Yes, it is disease causing’ or ‘no, it’s not.’ It means that there’s more work to be done to try to sort out if it is causing the condition,” Jain told Mississippi Today.

Benton’s report on Sawyer’s genetic test recommends genetic counseling and targeted testing of her parents to better understand the implications of this variant, but no further testing was done and no explanation was given as to why, according to the medical records.

Jordan said she became aware of the test and its results only after her case was concluded.

Benton declined to answer questions about Jordan and her daughter’s case, even though Jordan submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss her daughter’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

Benton told a group of public defenders in a recorded presentation about sex crimes, however, that before he came to UMMC in 2008, parents and anyone who was suspected of being associated with a child’s injury was “kicked out of the hospital.”

He said he reversed that policy so he could be sure to get a full history from parents and not overlook any possible medical explanations for a child’s injuries.

“That was part of their protocol (at the time). And I said ‘Alright, who am I supposed to get the history from? Who am I supposed to (talk to) to figure out if there’s a medical explanation for some of these bleeding findings?’” he told the group. “So we quickly reversed that.”

For the first three months while Sawyer was with a foster family, Jordan said she wasn’t allowed to see her, despite CPS visitation policy that states contact between the child and his or her parents must be arranged within 72 hours of that child being placed into foster care.

Shannon Warnock, a spokeswoman for CPS, said the agency can’t comment on specific cases, “including any exceptional circumstances that warrant policy adjustments.”

In December 2020, nine months after Jordan went into CPS custody, Jordan’s parents got a foster care license and got custody of Sawyer.

In doing so, that meant Jordan had to move out. She found a one-bedroom apartment she could afford.

Ultimately, the youth court judge concluded Sawyer was abused but it was unclear who inflicted the injuries, so she was returned to Jordan on April 5, 2021.

In the aftermath, Jordan has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, an anxiety disorder and depression. She mourns the milestones she missed during the 15 months Sawyer was taken from her.

“I missed my daughter’s first birthday,” Jordan said. “I missed her first Easter. I missed her first step. I missed a lot of firsts. And these are things I can never get back.”

The separation also affected Sawyer, now an outspoken 3-year-old who sometimes rolls her eyes at her mother and loves to dance.

Sawyer has to carry KeKe, a fuzzy blanket covered in llamas, with her wherever she goes, Jordan said. The baby blanket was the only one of her belongings she was able to keep while in state custody. She still has separation anxiety, and Jordan often has to reassure her she will not leave her again.

Jordan recently scheduled additional testing for Sawyer in New Orleans to confirm if she has the brittle bone disease. She said she waited because of the cost, and because for a long time, the idea of taking Sawyer to a doctor left her terrified.

The two now live in a two-bedroom house in Columbia with a large backyard. They’re trying to start over and create a new normal.

“Ever since they closed our case, I’ve just tried to be a mom,” Jordan said.

Lindsey Tedford, Tupelo

Lindsey Tedford of Tupelo rushed her 3-week-old son Cohen to the local emergency room at North Mississippi Medical Center on June 13, 2021. While her husband was holding their newborn and bent down to pick up a pacifier from the floor, Cohen had hit his head on the nearby crib, the parents told the nurses in the emergency room.

Cohen had bruising under both eyes and on his nose but was otherwise fine, the doctors told her.

The hospital never performed CT or MRI scans, medical records from the visit show.

But when Cohen was at a pediatric cardiologist appointment about two and a half months after the crib accident, the doctor noticed something concerning. Cohen’s head circumference had increased since his two-month checkup with his pediatrician. He scheduled an ultrasound two weeks later, and the results were “concerning for a brain bleed,” according to the baby’s medical records.

The doctor sent them to the North Mississippi Medical Center for a CT scan. It confirmed the ultrasound results: Blood had collected between the skull and the surface of the brain, and Cohen had a possible skull fracture.

The results triggered a chain of events that led to the Tedfords losing custody of Cohen for nearly five months. The state’s only child abuse pediatrician, Dr. Scott Benton, accused them of child abuse and diagnosed Cohen with “nonaccidental trauma.”

In recent months, doctors at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis have diagnosed Cohen, now over a year old, with a bleeding disorder called idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or ITP. Subdural hematomas and intracranial hemorrhage — both diagnoses Cohen received at UMMC — are rare complications of ITP.

Back in September of 2021, the North Mississippi neurosurgeon recommended operating on the brain bleed as soon as possible. Lindsey asked the doctor to transfer Cohen to Le Bonheur in Memphis and left the hospital to go home to get clothes for the trip. On her way back, she got a frantic call from her husband Blake: they had taken Cohen in a helicopter, and he didn’t know where they were taking him, she said.

“As soon as Blake left to go out of the room to follow the people taking Cohen to the helicopter, (people from Child Protective Services) were waiting on him to question him.”

Eventually a nurse manager told him Cohen was sent to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, she said.

A spokeswoman for North Mississippi Medical Center said the hospital aims to care for potential victims of child abuse “with love and respect.”

“We report child abuse to Child Protective Services in accordance with Mississippi regulations and treat as medically appropriate,” the spokeswoman said when asked how the hospital handles cases of suspected abuse and neglect. “UMMC maintains a Pediatric Sub-Specialty Clinic in Tupelo, which offers non-traumatic medical examinations and treatment for cases of suspected abuse and neglect.”

The Tedfords said they made phone calls to UMMC as they drove to Jackson. They eventually found Cohen in the emergency room.

They didn’t hear from Child Protective Services again until almost two weeks later — the day before Cohen was discharged into CPS custody.

CPS policy and state law do not require parents be informed they are being investigated for possible child abuse in any specific time frame.

“The Foster Care Policy manual does say that a parent ‘will be notified prior to, or as soon as safely possible, that his/her child is being placed in custody,’ but there is no specific time period for notifying the parent of the child’s removal,” said Shannon Warnock, a spokesperson for CPS.

She said the agency could not comment on specific cases.

Following more tests, Cohen was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. Neurology, hematology and ophthalmology consulted on his case.

Blood work revealed he was anemic, but medical records note a hematologist “… felt that anemia was most likely secondary to subdural hematoma.”

No other tests or scans were abnormal, according to the records.

About five days into Cohen’s hospital stay, Dr. Scott Benton introduced himself to her and her husband as the “staff forensic pediatrician,” Lindsey said.

“I didn’t know what that meant,” she said. “He said, ‘I’m going to record this session,’ and didn’t tell us a whole lot, just started asking questions.”

The couple relayed how Cohen had hit his head on his crib at 3 weeks old. Benton said the bleeding couldn’t have been caused by that, Lindsey said.

When she showed him pictures of Cohen’s bruised face and the bassinet, he said that didn’t “impress” him, she recalled.

Lindsey also told Benton about Cohen’s “traumatic” birth, but she said he told her the same — it didn’t impress him. During 17 hours of labor, both her and his heart rates dropped on several occasions, and she lost consciousness.

Cohen was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck.

Benton declined to answer questions about Lindsey and her son’s case, even though she submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss her son’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

Lindsey attempted to get the recording of her conversations with Benton from the Children’s Safe Center, the medical center Benton oversees, but was unable to reach an employee, she said. Another mother who attempted to get similar recordings was told she must have an attorney to do so.

At UMMC, a surgeon drilled small openings called burr holes into Cohen’s skull to relieve pressure from the bleeding. He recovered and was discharged from UMMC.

The Tedfords appealed to a CPS case worker to allow Cohen to stay with Blake’s mother, who lived about 20 minutes from their home. CPS tentatively agreed, pending a successful home visit.

On Sept. 22, 2021, officials from Child Protective Services took the baby back to Tupelo. The hospital had diagnosed his injury as “nonaccidental trauma to child.”

For months, the Tedfords’ lives were divided between two houses. CPS had also removed their then-3-year-old daughter Cullen Claire from the home under a safety plan, and she was staying with Lindsey’s parents.

“She kept asking, ‘Why can’t I go home with my mommy and daddy? Is my brother ever going to get better?’ We couldn’t tell her, ‘You can’t come home because these people think we’re abusing you,’” said Lindsey.

Cohen wasn’t sleeping well away from his home, either, and his grandmother was in a state of constant exhaustion.

Over the next several months, CPS visited the Tedfords’ home, and the couple took (and passed) a polygraph test at the end of October, Lindsey said.

At a December safety plan review, Cullen Claire’s court-appointed guardian recommended returning her home because of the detrimental impact on her mental health — contingent on Lindsey receiving a mental evaluation because of the postpartum depression she revealed to Benton at the hospital in their conversation.

Several court dates for Cohen in early January passed with no action from CPS or the prosecution. They finally went back to court at the end of January.

“Our lawyer presented dismissal, saying there was basically not enough evidence to say these people abused their children,” recalled Lindsey. “He said, ‘This has been going on for five months now, nothing’s happened, we haven’t been to trial, and we just now got medical records. How long is this going to go on, and this family is broken?’”

When the judge asked the prosecution if they would be ready for trial in the next month, the attorneys said no.

Cohen’s court-appointed guardian also recommended the child return home. The judge ruled in the Tedfords’ favor, but stated Cohen should remain under a CPS safety plan involving periodic home visits. The plan ended March 2, 2022.

Life for the Tedfords is, on the outside, back to normal. But a lot has changed.

In addition to the health scare with Cohen and frequent trips to Memphis for his doctor appointments for ITP, his sister Cullen Claire, now 4, is struggling.

“We’re looking into child therapy for her. She tells us all the time that she doesn’t think we love her, that no one likes her. She’s struggled at school,” Lindsey said, starting to cry. “It’s definitely caused a lot of trauma.”

Lindsey has also been to therapy to work through what happened.

She said any time there’s a minor accident — bumps, falls and scrapes — she gets worried.

“What would it take for my kids to go back into CPS custody?” she wonders.

Lauren Ayers, Madison

After an afternoon at the playground on July 24, 2018, Lauren Ayers of Madison came home with her 10-week-old twins and almost 2-year-old son.

Ayers’ husband was in Oklahoma for work, so she was left alone with the three boys. She made spaghetti for her older son and herself. After they ate, she started the bedtime routine for the twins, Eli and Conner. She changed Conner’s diaper, swaddled him and laid him in his bassinet in her bedroom.

She put the other twin, Eli, on the plastic diaper changing pad on top of the dresser where she changes the boys’ diapers in their nursery. She had Eli’s onesie undone, so the lower half of his body was pressed directly against the uncovered pad.

The three children’s screams and cries created a cacophony in her home. Eli was kicking and thrashing on the changing pad.

Over the sound of the cries, she heard a clicking noise behind her and turned around, with Eli still on the changing table. Her older son sometimes liked to stand on the glider and rock back and forth, and she’d often have to intercept him before he fell. This time, though, he was playing with a retractable tape measure.

Turning back around, she was horrified to see Eli had scooted himself backwards and had fallen, landing on the crown of his head on the hard floor.

She remembers the resounding thud. When she ran over to pick him up, he was crying, but then became limp and lost consciousness.

“I thought he had broken his neck … I couldn’t find my phone, I was running outside and screaming for anybody to help me,” Ayers recalled. “I finally remembered where my phone was and ran in and called 911. He was unconscious, but he was breathing.”

Ayers’ neighborhood in Flora was new at the time, and she said she was either so upset she wasn’t being clear about where she lived or the emergency response officials weren’t sure where she was. She offered to meet them at Mannsdale Upper Elementary School, about a mile from her house.

“I loaded everybody up, got there … three different fire departments came,” she said. “I kept asking this off-duty firefighter … ‘What do we need to do?’ And he said, ‘Look, if anything’s wrong with him, you want him in the care of an ambulance.’”

With Ayers’ husband out of town and her family in Destin, her best friend came to the school along with her husband.

When no ambulance had arrived 30 minutes later, “the off-duty firefighter was like, ‘You’ve got to get him to a hospital,’” she said. “So my best friend’s husband drove us (to the University of Mississippi Medical Center).”

Ayers’ friend stayed with her and Eli, who had regained consciousness, when he arrived in the emergency room.Two of Ayers’ other friends were also in the emergency room with them, along with her in-laws.

“Thank God people could come back in the ER (because) they were witnesses of everything that happened … They tried to get an IV in him … They stuck him probably over 12 times,” Ayers described. “They couldn’t get blood from him.”

The nurses started a procedure called “milking,” said Ayers, where they would put both hands on Eli’s legs and arms and squeeze the skin in opposite directions in an attempt to get blood to flow.

They checked his stats, ran tests and admitted him to the pediatric intensive care unit for the night. A neurosurgeon reassured Ayers and her family that while the injury was bad, Eli would recover.

A scan the next morning showed Eli’s brain bleed had not gotten any larger, so he was moved to a regular room. That day, Ayers said the nurse told her the forensic pediatrician wanted to go over what happened. Ayers had no idea what a forensic pediatrician was.

Ayers attempted to get a recording of her conversation with Benton to share with Mississippi Today, but was told by the Children’s Safe Center, the medical center Benton oversees, that she would have to get an attorney to obtain it.

But she well remembers how the conversation began.

“He goes on to explain his (Eli’s) injuries and then asked if I remembered (the actress) Natasha Richardson. And I was like ‘Yea, yea, from the ‘Parent Trap’,’” she said. “And he goes, you know, ‘she had the skiing accident … This is the same injury your child has.’”

Richardson suffered a head injury and died two days later in 2009.

Ayers was shocked. She thought maybe Benton was about to tell her something was very wrong.

Benton abruptly closed his notebook and looked at her, she said.

“He said, ‘You’re under a lot of pressure right now. You have three kids, you were home alone — postpartum (depression) is a real thing,’” she remembered. “‘Tell me what really happened.”

Benton’s notes from Eli’s medical records show his certainty that the baby was not injured the way Ayers said.

“The fractures are discontinuous (do not connect) and appear to represent separate impact sites,” his notes show. “… Bilateral fractures are not reported in single fall incidents except where the skull fractures are continuous across sutures or in cases of bilateral out bending from a posterior impact causing symmetrical fractures.”

He goes on to note his concerns are whether Eli was developmentally able to kick or slide himself backwards and whether his skull fractures are “consistent” with Ayers’ account of what happened.

An occupational therapist who later evaluated Eli noted he was “quite active for age and may be slightly ahead with developmental milestones.” Ayers also took a video of Eli scooting himself backwards off a diaper changing pad, which she provided to Mississippi Today. In the video, he is wearing the same onesie outfit he was wearing in photos from the hospital.

She said Benton then told her he believes she threw the baby against a wall.

Yet the “most traumatizing part” of the first meeting with Benton, she said, was when he “strips that baby naked, and he’s looking, I guess, for signs of abuse.”

He started taking pictures of the bruises and needle marks from when Eli was admitted in the ER. Ayers asked what he was doing, and he said he believed she had inflicted the bruises.

He argued with her that the bruises were not from attempts to draw blood, and that “milking” was against hospital policy.

“I kept saying, ‘Don’t you see the needle marks?’ I was screaming at the nurses, ‘These are needle marks, you see them and you gave them to him!’” said Ayers.

Her friend had written down the names of the nurses who treated Eli in the emergency room, and Ayers begged Benton to talk to them. Ayers found a nurse who showed Benton records that when Eli first came to the hospital, no bruising or marks were noted.

A pediatric general surgeon who reviewed Eli two days later noted “bruising to left hand with visible venous access attempt noted” and “IV to right foot.”

Benton backed off, she said. But Ayers’ anxiety had only increased.

“At that point I was like, ‘They’re going to take this baby from me,’” she said.

Benton declined to answer questions about Ayers and her son’s case, even though Ayers submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss Eli’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

At the next meeting with Benton, Ayers had family members with her, including her father-in-law, a pharmacist. One of Eli’s tests had come back showing he had slightly elevated liver enzymes, which Benton believed indicated trauma to the abdomen.

Ayers’ father-in-law asked to review the test results.

“He (my father-in-law) literally looked at him and said, ‘Dr. Benton, with all due respect, these are stress-related elevated enzymes,’” she recalled. “‘These are not trauma-level numbers.’”

Benton said Eli would need to do a CT with contrast that requires fasting and radiation. Radiation exposure is particularly concerning in children because they are more sensitive to radiation. And because they have a longer life expectancy than adults, that results in a larger window of opportunity for them to experience radiation damage.

Ayers and her father-in-law objected to the CT, noting Ayers’ husband, Drew, had a kidney condition that made dehydration particularly dangerous, and there was a chance Eli might have the same issue.

But Benton insisted, and they relented.

In the paperwork under “clinical history” for the CT scan, it states: “Reported new bruising on the abdomen. Concern for blunt trauma to abdomen.” There had never been any mention of abdominal bruising in the medical records or to Ayers up until that point, and the CT was performed two days after Eli came to the hospital.

The scan came back normal.

“No evidence of blunt trauma to the abdomen. No acute fractures or dislocations,” the report stated.

Eli was discharged but subjected to another full body X-ray several weeks after he left, according to records. A case worker from Child Protective Services visited Ayers’ home and cleared Eli to return. Several weeks later, a Madison County sheriff’s investigator also interviewed Ayers.

The case was closed that day, the incident report stated.

What haunts Ayers even four years later is wondering what happens to mothers without the resources she had: the ability to hire an attorney, a family member in the medical field to sit in on meetings with Benton and the support of friends and family who were in the emergency room and hospital with her.

“This man should have some more oversight … if you’re going to subject a 10-week-old to all these tests, two MRIs, a CT, X-rays, you should have your evidence in order,” said Ayers, who said she struggled “with some pretty dark days” after the accusations from Benton and the experience in the hospital.

Ayers filed a complaint with the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure in March of last year. In her complaint, she highlighted the unexplained “new bruising to abdomen” on the notes for his CT – bruising that was never mentioned anywhere else in his medical records.

“I would say, about 10 doctors signed off that my child (the patient) had ZERO bruising anywhere on his body upon admittance to the hospital … Scott Benton couldn’t ethically order this CT with contrast on my child bc (because) his liver enzymes weren’t actually elevated enough to need it,” she wrote. “ … Before I take matters further, I’d really like someone to call me, asap.”

She never heard anything back.

Editor’s note: Kate Royals, Mississippi Today’s community health editor since January 2022, worked as a writer/editor for UMMC’s Office of Communications from November 2018 through August 2020, writing press releases and features about the medical center’s schools of dentistry and nursing.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=210275

Mississippi Today

‘You’re not going to be able to do that anymore’: Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws

Diners turned watchful eyes to the stage as Jackson Police Chief Joseph Wade took to the podium. He visited Stewpot Community Services during its daily free lunch hour Thursday to discuss new state laws, which took effect two days earlier, targeting Mississippians experiencing homelessness.

“I understand that you are going through some hard times right now. That’s why I’m here,” Wade said to the crowd. “I felt it was important to come out here and speak with you directly.”

Wade laid out the three bills that passed earlier this year: House Bill 1197, the “Safe Solicitation Act,” HB 1200, the “Real Property Owners Protection Act” and HB 1203, a bill that prohibits camping on public property.

“Sleeping and laying in public places, you’re not going to be able to do that anymore,” he said. “There’s a law that has been passed that you can’t just set up encampments on public or private properties where it’s a public nuisance, it’s a problem.”

The “Real Property Owners Protection Act,” authored by Rep. Brent Powell, R-Brandon, is a bill that expedites the process of removing squatters. The “Safe Solicitation Act,” authored by Rep. Shanda Yates, I-Jackson, requires a permit for panhandling and allows people to be charged with a misdemeanor if they violate this law. The offense is punishable by a fine not to exceed $300 and an offender could face up to six months in jail. Wade said he’s currently working with his legal department to determine the best strategy for creating and issuing permits.

“We’re going to navigate these legal challenges, get some interpretations, not only from our legal department, but the Attorney General’s office to ensure that we are doing it legally and lawfully, because I understand that these are citizens,” he said. “I understand that they deserve to be treated with respect, and I understand that we are going to do this without violating their constitutional rights.”

Wade said the Jackson Police Department is steadily fielding reports of squatters in abandoned properties and the law change gives officers new power to remove them more quickly. The added challenge? Figuring out what to do with a person’s belongings.

“These people are carrying around what they own, but we are not a repository for all of their stuff,” he said. “So, when we make that arrest, we’ve got to have a strategic plan as to what we do with their stuff.”

Wade said there needs to be a deeper conversation around the issues that lead someone to becoming homeless.

“A lot of people that we’re running across that are homeless are also suffering from medical conditions, mental health issues, and they’re also suffering from drug addiction and substance abuse. We’ve got to have a strategic approach, but we also can’t log jam our jail down in Raymond,” Wade said.

He estimates that more than 800 people are currently incarcerated at the Raymond Detention Center, and any increase could strain the system as the laws continue to be enforced.

“I think there’s layers that we have to work through, there’s hurdles that we are going to overcome, but we’ve got to make sure that we do it and make sure that my team and JPD is consistent in how we enforce these laws,” Wade said.

Diners applauded Wade after he spoke, in between bites of fried chicken, salad, corn and 4th of July-themed packaged cakes. Wade offered to answer questions, but no one asked any.

Rev. Jill Buckley, executive director of Stewpot, said that the legislation is a good tool to address issues around homelessness and community needs. She doesn’t want to see people who are homeless be criminalized, but she also wants communities to be safe.

“I support people’s right to self determine, and we can’t impose our choices on other people, but there are some cases in which that impinges on community safety, and so to the extent that anyone who is camping or panhandling or squatting and is a danger to themselves and others, of course, I fully support that kind of law. I don’t support homelessness being criminalized as such,” Buckley said.

Many of the people Wade addressed while they ate Thursday said they have housing, don’t panhandle, and shouldn’t be directly impacted by the legislation. But Marcus Willis, 42, said it would make more sense if elected officials wanted to combat the negative impacts of homelessness that they help more people secure employment.

“There ain’t enough jobs,” said Willis, who was having lunch with his girlfriend Amber Ivy.

The two live in an apartment together nearby on Capitol Street, where Ivy landed after her mother, whom Ivy had been living with, suffered a stroke and lost the property. Similarly, Willis started coming to eat at Stewpot after his grandmother, whose house he used to visit for lunch, passed away.

Willis holds odd jobs – cutting grass, home and auto repair – so the income is inconsistent, and every opportunity for stable employment he said he’s found is outside of Jackson in the suburbs. The couple doesn’t have a car.

Making rent every month usually depends on their ability to find someone to help chip in, said Ivy, who is in recovery from substance abuse. She said she’s watched problems surrounding homelessness grow over the years in Jackson. Ivy grew up near Stewpot and has lived in various neighborhoods across the city – except for the times she moved out of state when things got too rough.

“There was just moments where I just had to leave,” Ivy said. “Sometimes if you hit a slump here, there’s almost no way for you to get out of it.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'You're not going to be able to do that anymore': Jackson police chief visits food kitchen to discuss new public sleeping, panhandling laws appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

This article primarily reports on new laws in Jackson, Mississippi, targeting public sleeping, panhandling, and squatting, focusing on statements by Police Chief Joseph Wade and community perspectives. The coverage presents the legislative measures—authored by Republican and independent lawmakers—with a tone that emphasizes law enforcement challenges and community safety, reflecting a conservative approach to homelessness as a public order issue. While it includes voices concerned about criminalization and the need for social support, the overall framing centers on law enforcement and property protection. The article maintains factual reporting without overt editorializing but leans slightly toward a center-right perspective by highlighting legal enforcement as a solution.

Mississippi Today

Medicaid cuts could be devastating for the Delta and the rest of rural America

Note: This story first published in Stateline, which is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.

LAKE PROVIDENCE, La. — East Carroll Parish sits in the northeastern corner of Louisiana, along the winding Mississippi River. Its seat, Lake Providence, was a thriving agricultural center of the Delta. Now, the town is a shell of its former self. Charred and dilapidated buildings dot the small city center. There are a few gas stations, a handful of restaurants — and little to no industry.

Mayor Bobby Amacker, 79, says at one point “you couldn’t even walk down the street” in Lake Providence’s main business district because “there were so many people.”

“It’s gone down tremendously in the last 50 years,” said Amacker, a Democrat. “The town, it looks like it’s drying up. And it’s almost unstoppable, as far as I can tell.”

Now, East Carroll residents stand to lose even more. Like many people in Louisiana, they received a lifeline when the state expanded Medicaid to more low-income adults in 2016. Expansion drove Louisiana’s uninsured rate to the lowest in the Deep South, at 8% in 2023 for working-age adults, according to state data, despite it having the highest poverty rate in the U.S. that year.

This week, both chambers of Congress approved President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful” tax and spending bill. It includes more than $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid, the joint state-federal health insurance program for poor families and individuals, to help pay for tax cuts that mostly benefit the rich. The legislation would cause 11.8 million more Americans to become uninsured by 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The bill includes new work rules for Medicaid recipients and would require them to verify their eligibility more frequently. It also would limit a financing strategy that states have used to boost Medicaid payments to hospitals.

Republicans say enrollees are taking advantage of the Medicaid program and getting benefits when they shouldn’t be. They say the program costs too much and states are not paying their fair share.

The Delta region, which includes communities in both Louisiana and Mississippi, would suffer under such large cuts. But in Louisiana — where almost half of the state depended on Medicaid in 2023, the Louisiana Department of Health reported — the cuts could be ruinous. Louisiana could lose up to $35 billion in federal Medicaid support over the next decade, according to KFF, a health policy research group. Mississippi, which never expanded Medicaid, could still lose up to $5 billion.

Residents are watching with apprehension, fear and, sometimes, anger, wondering how Congress could be so blind to how much they are struggling.

“If they take that away from us and everyone that really needs it, that’s going to be bad,” said Sherila Ervin, who lives 20 minutes up the road from Lake Providence in Oak Grove and has Medicaid coverage.

Medicaid work requirements and other health care provisions in the bill ignore the reality of living in poorer rural communities, where people struggle to find the jobs, transportation and internet access required to meet the rules, according to interviews with people and providers in the Delta region.

Even though Louisiana and Mississippi have taken very different approaches to Medicaid — one expanded eligibility under the 2010 Affordable Care Act and the other didn’t — both rely heavily on the program to sustain access to medical care for all their residents.

On a hot summer day in June, Ervin walks into the bare-bones 99-cent store in downtown Lake Providence. As she looks over some clothing, she says she’s heard about the potential Medicaid cuts. But she hadn’t heard about the work requirements, and is shocked they’re even on the table.

“I don’t like that. I don’t think they should put a stipulation on that,” Ervin says, exasperated that she would have to report her work hours. It’s hard enough as it is, she says, to thrive in this community.

READ MORE: In the Deep South, health care fights echo civil rights battles

Ervin, 58, has been working at Oak Grove High School in the cafeteria, serving hot plates to children for two decades. She says it’s one of the good, steady jobs available in this area, but her income is only around $1,500 per month.

Ervin’s job offers health benefits, but she can’t afford the premiums on her salary. She relies on Medicaid for care, including medications for her high blood pressure.

In East Carroll Parish, around 46.5% of people live below the poverty level, meaning the area is overwhelmingly poor, at over four times the national poverty rate, with a median income of $28,321. For Black households, the figure is a mere $16,690.

Expansion was a lifeline for people such as Ervin. Louisiana offers Medicaid to people who earn below 138% of the federal poverty line — currently about $22,000 a year for an individual.

“Sometimes you can work, but then when you work, you still can’t pay to get help,” Ervin said.

It’s a similar economic situation an hour away across the river. Poverty is about three times the national rate in Washington County, Mississippi, where residents in the city of Greenville lament the consequences of not being able to avoid destructive medical debt, which can keep them stuck in a cycle of gig work and of living paycheck to paycheck.

Greenville, the county seat, is among the fastest-shrinking cities in the U.S. It’s still one of the larger rural cities in Mississippi, with coffee shops, restaurants, hotels, a regional hospital and several big-box stores. But the downtown has just a few small businesses and a bank, and residents say jobs are hard to find.

Greenville resident April McNair, 45, remembers giving birth 17 years ago, long before Mississippi extended postpartum Medicaid to a full year. She had Medicaid coverage during pregnancy, but was kicked off shortly after giving birth, despite having post-delivery complications.

The result was a trip to the emergency room and a $2,500 bill she couldn’t cover. Right after giving birth, McNair looked for work. She said potential employers often told her that she was overqualified because she had a master’s degree.

“I had to kind of figure out how to make my ends meet,” McNair said. “I ended up with a significant bill, all because I did not have Medicaid.”

McNair feels like Mississippi leaders are making a mistake by continuing to reject full Medicaid expansion.

“That’s a selfish move. To me, they’re selfish,” McNair said, adding that now she’s worried for neighbors in Louisiana who may lose the lifeline she wishes she had.

“God forbid, hypothetically speaking, what if one of them meets their demise because of this bill that [Congress] passed?”

Hard to thrive

Mississippi experienced its first taste of equalized access to medicine in the late 1960s.

Delta Health Center, the first federally funded health center in the nation, opened during the peak of the Civil Rights Movement in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou, about an hour north of Greenville. The center vowed to care for anyone regardless of race or ability to pay in a region plagued with poverty, poor health and discrimination — and continues to do so to this day.

It was a significant opportunity for generations of African Americans who had gone without health care, in a place where people had no access to clean drinking water, running sewage systems or even food, said Robin Boyles, chief program planning and development officer at Delta Health Center.

But it wasn’t easy for the clinic to mobilize support, even though it was clearly needed. Before its opening, it faced pushback from politicians and even doctors. In a 1966 clipping from a local newspaper, the white-owned Bolivar Commercial, the editorial board railed against the new clinic, saying it would “lead further to socialized medicine.”

The situation is certainly better in Mississippi and Louisiana than it was in the 1960s, but critics say the Medicaid cuts could reverse hard-fought progress.

People who live in the Delta are fiercely proud of their communities, but conditions there make it hard to thrive.

Black residents, who are the overwhelming majority, have had a particularly hard time. After the Civil War, many were relegated to sharecropping of cotton and corn for subsistence. Meanwhile, an elite white class of plantation owners and investors amassed enormous amounts of wealth.

A 2001 report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights described the area as one with “limited economic resources; inadequate employment opportunities; insufficient decent, affordable housing; and poor quality public schools.”

“We have a lot of patients that are one health issue away from either being out of a job or being bankrupt because of a trip to the emergency room,” said Dr. Brent Smith, a physician at a primary care clinic at Delta Health System in Greenville.

Even some of the most vulnerable people, such as new moms in Mississippi, still struggle to get basic care, in part because the state has left billions of dollars in federal funding for Medicaid expansion on the table, said Dr. Lakeisha Richardson, an OB-GYN at Delta Health System.

“There are a lot of maternal [care] deserts in Mississippi where women have to travel 60 miles or more just to get prenatal care and just to get to the closest hospital for delivery,” Richardson said. “And I don’t see that getting any better in Mississippi and in rural areas.”

Richardson says nearly all her patients are working moms, many of whom would really benefit from having Medicaid expansion.

“America doesn’t realize that there are people out here struggling for no reason of their own,” she said.

That’s why Medicaid expansion in Louisiana in 2016, much like the community health center movement in Mississippi, was a bright spot in the rural South, said Smith.

“Louisiana expanded Medicaid, a surprising move in the South to see any state expand,” Smith said. “They saw it for what it was, which was a very real opportunity to assist this specific group of patients.”

In Mississippi, 20 rural hospitals are at immediate risk of closure, according to a recent report, more than double the number at risk in Louisiana. In many cases, Medicaid is the largest and most reliable payer for rural hospitals. While Louisiana’s overall uninsured rate plummeted to 8.3% by 2023, in Mississippi it was 10.5%.

“Unlike a lot of our Southern peers, we have not had the same level of closures of facilities,” said Courtney Foster, senior policy adviser for Medicaid, with the nonprofit Invest in Louisiana.

“Medicaid was like a real lifeline for people in transition. Oftentimes it was people who had lost their jobs and were just looking to get back on their feet.”

Now, the new work and reporting requirements could put that progress at risk.

In East Carroll Parish, finding a job — let alone a good-paying one with health benefits — is difficult, says Rosie Brown, executive director at the East Carroll Community Action Agency, a nonprofit that helps low-income people with their rent and utility bills. Many of the jobs available in town pay minimum wage, just $7.25 an hour.

Brown loves living in Lake Providence; this is where her family is. She doesn’t want to move but wishes the government would invest more in her community — not take away benefits that help people who are hanging on by a thread.

“We have one bank. We have one supermarket,” she said. “Transportation isn’t easy either.”

Local infrastructure is so limited, she’s even heard of some people charging residents $20 for a ride to Walmart. Some people have to hitch a ride an hour away to go to work, she said.

“There’s nowhere to go,” Brown said.

Dominique Jones works at the local library, where she helps roughly 75 to 85 people per month apply for programs such as Medicaid and food assistance. Many of the residents she helps don’t have access to the internet or even a computer, a real barrier for people who’d be required to report their working hours to state Medicaid officials.

“This town right here is made up of a lot of old people that need Medicaid and Medicare. And without it, they wouldn’t have any kind of health care at all,” Mayor Amacker said.

Even a job in local government in Lake Providence doesn’t offer affordable health insurance.

Nevada Qualls, 25, sits across from Amacker’s office. She earns just $12 an hour as a cashier at city hall. The low pay means she qualifies for Medicaid expansion coverage, which is good because she can’t afford the premiums for private insurance.

“I feel like there should be a higher threshold for people that can get Medicaid, because they’re still struggling,” she said.

At the 99-cent store, school district worker Ervin wonders whether state and federal leaders understand what it’s like to live in her community, urging them to visit and see for themselves.

“They want to do stuff for the rich people that’s already rich,” she said. “What are they doing? It’s almost like there’s no common sense with them.”

‘The tremble factors’

While leaders in the U.S. Senate were working into the night this past weekend debating Trump’s tax and spending bill, Greenville resident Jennifer Morris was praying for the pain to stay away.

Morris, 44, has hemicrania continua, a headache disorder that causes constant pain on one side of her head. There’s no underlying trigger and no cure. Her doctors help her keep the pain to a minimum with regular treatments that include dozens of injections into her head.

“It doesn’t take the pain away,” she said during a late-night gathering in Greenville’s Greater Mount Olivet Missionary Baptist Church in June. “It does reduce the pain so that I’m able to function. But it’s rough.”

Morris is worried about the looming Medicaid cuts. She qualifies for Mississippi Medicaid because her condition counts as a disability, and she depends on the coverage to afford her medications.

Morris’ Medicaid may be safer than that of her Delta neighbors in Lake Providence, as some of the most dramatic Medicaid changes being considered — such as work requirements — target Medicaid expansion states only.

But Mississippi could be hurt by a provision in the Senate bill that would target a strategy states have used to boost the Medicaid dollars they get from the federal government.

Mississippi could see a major hit to its Medicaid funds, which “would be a tremendous decrease in revenue for the state,” harming “services and access to care,” says Mitchell Adcock, executive director at the Center for Mississippi Health Policy.

“It would be just the opposite of expansion. It would be a contraction for the Medicaid program in the state,” he said.

Leonard Favorite, a pastor who was attending the same event at Mount Olivet Church, as Morris, says he grew up on a plantation in Louisiana and worked his way out of poverty by joining the Air Force. This type of journey is hard, he said, when you’re already starting from so far behind. He thinks the “big, beautiful bill” will create more roadblocks for poor people.

READ MORE: Glaucoma-related vision loss is often preventable, but many can’t afford treatment

“You have people who are already living below the poverty line and they will certainly be submerged into poverty at unspeakable levels,” said Favorite, 70.“ That seems to be the trend of this administration from the point of view of looking from the outside.

“Poor people are beginning to feel the tremble factors of an administration that caters toward the rich.”

National researchers estimate that up to 132,000 Louisianans who gained health insurance under expansion could lose it under work rules.

But national reports that rely on census data likely underestimate the potential Medicaid losses. For example, while 2023 census data show 47% of East Carroll Parish was on Medicaid, state health data reviewed by Stateline and Public Health Watch suggests the number is more like 64%. Similarly statewide, census data showed about a third of Louisianans were on Medicaid. State data shows that percentage is closer to 46.5%.

Experts such as Joan Alker at the Georgetown Center for Children and Families say the undercounts nationally are a well-known issue among researchers, but it’s difficult to correct because the quality of state reporting can be so uneven.

State Medicaid funding is also at risk. For years, both Mississippi and Louisiana have relied on revenue generated through a financing tool — known as a provider tax — to draw down more federal dollars and boost Medicaid reimbursements to providers. But congressional Republicans hope to limit states’ ability to collect those taxes.

Depending on how Congress restricts provider taxes, Mississippi could lose hundreds of millions in federal Medicaid funding, crucial in a state with such a high uninsured rate, said Richard Roberson, president and CEO of the Mississippi Hospital Association.

“It’s unavoidable that when you’re taking that much money out of the system, that there’s not going to be some repercussions felt even in non-Medicaid expansion states like Mississippi,” Roberson said.

Last week, the Louisiana Hospital Association signed a statement calling the package of Medicaid cuts before Congress “historic in their devastation.”

From her small, sunny office in East Carroll Parish, nurse Jennifer Newton can’t understand the attacks on Medicaid.

Newton, who grew up one parish over in West Carroll, is executive director of the Family Medical Clinic, a community health center in Lake Providence and one of the few health providers in town. She says 50% of the clinic’s patients have Medicaid insurance.

Newton has worked in health care in the area for decades and watched as Medicaid expansion made it possible for more patients to access and afford health care they desperately needed, including preventive services. “It’s absolutely helped,” she said. “Absolutely.”

In 2015, the year before Louisiana expanded Medicaid, the uninsured rate among working-age adults in East Carroll Parish was nearly 35%. By 2021, that number was 12.7%.

“Why are we going back?” Newton asked. “We’ve made so much progress.”

Republican supporters of work requirements, including Louisiana representative and U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson, argue they will encourage people to find jobs and ensure Medicaid goes to people who need it most. But according to KFF, a majority of Louisiana adults with Medicaid — 69% — already work.

Brian Blase, president of the Paragon Health Institute, a conservative policy group that is working with Republicans to formulate Medicaid cuts, is not concerned about eligible people losing coverage, as has happened under previous work requirement efforts. He says the bill has built in exceptions for certain people and requirements “can be met by not just work,” so “concerns seem pretty overstated.”

Medicaid recipients also can meet the requirement by volunteering or attending school for 80 hours per month.

“It’s hard for me to understand that there are areas in the country where there’s not jobs. There’s always work to be done,” Blase told Stateline. Blase said he believes Medicaid is “the government conditioning welfare for able-bodied working-age adults.”

But advocates and experts predict East Carroll, where internet access is notoriously bad, would experience results similar to when Arkansas instituted Medicaid work requirements in 2018: People disenrolled because of lack of awareness and confusion over the policy, as well as paperwork errors — not because they weren’t working enough.

“Unless the beneficiary can navigate that red tape, they’re going to lose coverage and become uninsured,” said Benjamin Sommers, a health economist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Data shows Arkansas’ experiment did not increase employment, Sommers said, and instead led to more people reporting medical debt and delaying care because of cost.

‘Take a step back’

People in the Delta — where the legacy of government neglect and discrimination are all around — want politicians to visit their towns and see the barriers people face trying to improve their lives and stay healthy.

“People spent their lives uninsured,” said Amy Hale, a nurse practitioner at East Carroll Medical clinic. “Medicaid expansion allowed them to get in here and be treated.”

Lake Providence residents are scared they may find themselves in a similar situation as McNair and other people across the river in Greenville: working, uninsured, and too poor to access health care.

Recent estimates show up to 317,000 Louisianans could lose Medicaid health insurance under Trump’s tax bill. Nearly 33,000 in Mississippi.

“People are actually trying,” McNair said. “I really wish [lawmakers] would look at it from a different lens. What if it was their kid? Or they didn’t have the salaries they have now and your baby is ill. … Like really take a step back and think about what it is that you’re doing.”

This story is part of “Uninsured in America,” a project led by Public Health Watch that focuses on life in America’s health coverage gap and the 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

Stateline reporter Shalina Chatlani can be reached at schatlani@stateline.org. Public Health Watch reporter Kim Krisberg can be reached at kkrisberg@publichealthwatch.org.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Medicaid cuts could be devastating for the Delta and the rest of rural America appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article presents a clear perspective sympathetic to low-income and rural communities affected by Medicaid cuts. It highlights the hardships faced by residents in Louisiana’s and Mississippi’s Delta regions, emphasizing poverty, limited job opportunities, and the critical role Medicaid plays in health access. While it reports Republicans’ arguments for work requirements and cost control, the language and framing focus more on the negative consequences of cuts and the struggles of vulnerable populations. This tone and focus suggest a center-left bias, favoring expanded social safety nets and critical of policies perceived to harm the poor.

Mississippi Today

Mother calls for man exonerated of raping and murdering her child to go free

Prosecutors fighting the release of death row inmate Jimmie Duncan after a judge found him “factually innocent” of raping and murdering 23-month-old Haley Oliveaux are “not speaking for Haley’s family,” her mother says.

Speaking publicly for the first time, Allison Layton Statham called for Duncan to go free in a July 22 bail hearing. “This innocent man is on death row,” she told Mississippi Today. “Justice needs to be done.”

In April, a judge threw out Duncan’s conviction, questioning their conclusions and citing the failures of his court-appointed counsel.

Prosecutors have appealed the judge’s decision and are fighting his release on bail, saying Duncan poses both a flight risk and “a safety risk to not only the victim’s family, but also the general public.”

Statham disagreed and said she wants all of the evidence, including a sealed video of a bite-mark expert examining her child’s body, made available so that everyone can know the truth. “Authorities are still wanting to bury the truth,” she said. “What they did was railroad him.”

READ MORE: A March 2025 Verite News and ProPublica investigation into the Jimmie Duncan conviction

For a long time, Haley’s paternal aunt, Jennifer Berry, awaited word of Duncan’s execution, she said. “We’ve mourned quite a few people in our family, and we have never mourned like we mourned when that child died.”

Since talking with a documentary filmmaker in February and digging into the case, she believes he should go free. “I’ve been in turmoil since realizing this,” she said. “He’s a young man who was falsely accused of a crime he didn’t commit.”

She has petitioned prosecutors, the attorney general and the governor for a meeting but has yet to receive a reply.

The judge’s dismissal marks at least 10 wrongful convictions involving pathologist Dr. Steven Hayne, who has since died, or bite-mark expert Michael West, who once claimed he matched a suspect’s teeth to a half-eaten bologna sandwich. Eight of these wrongful convictions happened in Mississippi.

In 1994, the American Board of Forensic Odontology suspended West for a year for overstating credentials and misidentifying bite marks, and a dozen years later, he was forced to resign from the American Board of Forensic Pathology.

In 2008, the state of Mississippi barred Hayne from doing autopsies. He once wrote in his autopsy report about removing and examining a victim’s ovaries. The problem? The victim was male.

That same year, Levon Brooks and Kennedy Brewer were exonerated after spending a combined 30 years in prison. West’s bite-mark testimony helped convict Brooks of the rape-murder of a 3-year-old girl in Noxubee County. When another 3-year-old girl was raped and killed, West gave bite-mark testimony that helped lead to a death sentence for Brewer.

DNA discovered the truth: a serial killer had raped and murdered both girls. He confessed to his crimes, and Brooks and Brewer were freed.

It remains unknown how many other wrongful convictions these experts may have played a role in. Hayne once said he conducted up to 30,000 autopsies in Mississippi. West has said he analyzed more than 300 bite marks and investigated more than 5,000 deaths. He no longer believes bite marks should be used in court and did not respond to requests for comment on the dismissal of Duncan’s conviction.

Berry felt compelled to come forward now and call for a review of each case in Louisiana and Mississippi involving these discredited experts, she said. “Every case they put their fingers on needs to be reopened and examined.”

‘I wasn’t going to lie for them’

On the morning of Dec. 18, 1993, Statham said as she left for work Oliveaux was bouncing on her bed, tossing her “moo cow” in the air. She said she left her daughter in the care of the 25-year-old Duncan, whom she loved and had been living with for several months.

Duncan, who has maintained his innocence for more than three decades, told police he made Oliveaux oatmeal for breakfast and put her in the bathtub, where the water measured less than 3.5 inches. While doing dishes, he said he heard a noise and found her face down in the water. He said he grabbed her out of the tub and ran next door. The neighbors, paramedics and doctors were unable to save the life of Oliveaux, who had suffered recent seizures.

When Statham said she arrived at the emergency room, Duncan was distraught, apologizing over and over. Police charged Duncan with negligent homicide.

At the hospital, when West Monroe Police Detective Chris Sasser examined the body and saw the girl’s anus dilated and “laying open,” he concluded she “had been sodomized,” according to the police report. “It was a horrible sight.”

Rather than use a nearby pathologist, then-District Attorney Jerry Jones had the girl’s body transported two hours away to Mississippi for Hayne to do the autopsy. After the pathologist examined Oliveaux, he called in West to examine suspected bite marks.

Video captures West’s initial examination, starting at 9:35 p.m. He mentions a bruise on her left elbow, possible abrasions and contusions, and visible diaper rash. No mark can be seen on her cheek, and West makes no mention of one.

Twenty minutes later, Hayne telephoned Detective Sasser and said at about the time of the child’s death, she suffered lacerations and penetration to the anus, which the pathologist attributed to sexual assault, as well as multiple contusions to multiple surfaces on the body and lacerations and contusions to the scalp, according to the police report.

Hayne also said there were adult bite marks on the child made at or about the time of death and asked for the suspect’s dental molds.

After receiving this information, Sasser contacted a prosecutor, and the charge was upgraded to first-degree murder, which can carry a death penalty in Louisiana.

After the molds arrived the next day, the video resumed. West can be seen jamming a mold of Duncan’s teeth into the child’s cheek. West identified these as bite marks belonging to the suspect.

Hayne did the autopsy. He concluded that Haley’s death was a homicide, that her injuries suggested she had been sexually assaulted at or about the time of her death and that she had been forcibly drowned.

Other pathologists questioned Hayne’s conclusions. A rape kit came back negative. The Louisiana State Crime Lab tested Duncan’s clothing, the child’s clothing and her bath toys for any seminal fluid. There was none.

In the days following her daughter’s death, Statham said prosecutors called her into their office. She said they asked her if her daughter ever said or implied that Duncan wanted her to suck his penis like a baby bottle.

She told Mississippi Today that her toddler daughter could hardly speak. “She could say, ‘I want burgers,’ or ‘I want M&Ms,’” she said.

After she told them no, she said they replied, “If you don’t tell the truth, you could be implicated.”

She was 21 at the time. “My baby died, and the man I loved had been hauled off,” she said. “It was very intimidating. I was scared. But I wasn’t going to lie for them.”

Months later, police got a statement from jail inmate Michael Cruse. He quoted Duncan as saying the baby pointed at his penis and he said “something about a bottle or bobble.” Cruse later testified that Duncan said he blacked out and when he came to, he was trying to have sex with the baby and killed her because he “couldn’t get the baby to be quiet.”

To demonstrate his innocence, Duncan took a polygraph test. He reportedly showed no deception when he said he didn’t kill the child or hold her head underwater. Jurors never heard this, because polygraphs are inadmissible as evidence.

By the time the trial began in 1998, much of the important physical evidence was gone. The rape kit had been lost. So had Hayne’s autopsy slides. Samples of her blood that no one had tested for toxicology — a standard practice for autopsies — had been destroyed. So had Hayne’s detailed reports on his slides.

All that experts had available to examine were Hayne’s autopsy report and a few photos of the child’s body and injuries.

In his opening remarks at the 1998 murder trial, the district attorney said Duncan “rode that baby like a bull” and “in a sexual frenzy … bit her behind the ear … bit her elbow … She screamed, and she died in a bathtub full of water so bloody you couldn’t see the bottom.”

With West’s credentials now under question, prosecutors relied on another expert, who looked at West’s photos and identified Duncan as the one who made bite marks on the child. That expert didn’t see West’s video. Neither did the defense experts. Neither did the jury.

Hayne backed up the prosecution theory that Duncan drowned the child to cover up his sexual assault. He told jurors the bruise on her head was “consistent with a digit, such as a thumb or finger, pressing down on the back of the head.”

Asked if the child could have suffered a seizure, Hayne said no because “the brain showed no sign of seizure activity.”

Hayne testified that the child wouldn’t have survived her anal injuries, and another doctor told jurors there would have been so much blood, it would be like someone having their head cut off.

But police never found a drop of blood anywhere in the house, never found any evidence of cleaning. The detective later said if there had been any blood or semen at the scene, they would have discovered it.

Hayne testified that fragmented tomato, pickle and onion were in the child’s stomach, but no oatmeal — a detail prosecutors seized on as proof that Duncan concocted this cover story to conceal his horrific crime.

When police arrived, they found oatmeal in the kitchen, in the bathtub and on Duncan’s clothing. The neighbor saw uncooked oatmeal when he cleared Oliveaux’s throat before performing CPR.

The prosecutors told jurors the uncooked oatmeal was proof he planted it.

The jury convicted Duncan and sentenced him to death.

‘Bad medicine, bad science and bad lawyering’

Tucker Carrington, who wrote a book on Hayne and West with journalist Radley Balko, “The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist,” said the Louisiana case bears similarities to the case of Jeffrey Havard, convicted of capital murder for allegedly raping and killing an infant in Natchez in 2002, thanks to Hayne’s testimony.

Havard has said he was bathing his girlfriend’s 6-month-old baby, Chloe Britt, when she slipped from his hands and hit her head on the toilet.

But as in Duncan’s case, law enforcement officers thought the baby had been sexually assaulted. At trial, a parade of doctors and nurses testified about anal rips and tears they saw, describing the worst anal trauma they had seen, and prosecutors called Havard a monster.

The autopsy report, however, showed no such damage, only anal dilation and a small contusion. The rape kit came back negative.

Despite that, Hayne’s testimony backed the prosecution’s theory of sexual assault, and Havard was sentenced to Mississippi’s death row.

After examining the case, renowned pathologist Dr. Michael Baden concluded that Britt’s injuries were consistent with her being accidentally dropped and that she wasn’t sexually assaulted. “Dilation of the anus occurs normally in children when they die as muscles relax and when seen by a casual observer can be misinterpreted as evidence of perimortem penetration,” he said.

Other pathologists agreed with Baden that the anal dilation had been misread as abuse, and in 2014, Hayne told a reporter he didn’t believe a rape took place. He said the anal contusion could have resulted from a bowel movement.

He originally testified that the baby had died from shaken baby syndrome. Now he said he didn’t believe that was true because science had since determined such conclusions were flawed.

At least 37 people have been exonerated in shaken baby cases after being wrongly imprisoned, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

After a three-day hearing where the defense called Hayne to testify, the trial judge reduced Havard’s sentence from death to life. His appeal for freedom is now pending in U.S. District Court.

Havard’s lawyer, Graham Carner of Jackson, said the case is filled with “bad medicine, bad science and, frankly, bad lawyering.”

After a three-day hearing where the defense called Hayne to testify, the trial judge reduced Havard’s sentence from death to life. His appeal for freedom is now pending in U.S. District Court.

“Innocence is different than not guilty, and innocence is different than you didn’t get a fair trial,” Carner said, “but I believed as soon as I dug into Jeffrey’s case that he was an innocent man and I believe that to this day.”

‘Science, like law, evolves over time’

The damage that Hayne and West have done to Mississippi is immense, said former state Supreme Court Justice Oliver Diaz Jr., and he is stunned the state has never reviewed their cases for possible wrongful convictions.

“They operated in Mississippi for years unchecked,” he said. “Mississippi used Hayne as the state medical examiner, even though he did not meet the statutory qualifications.”

Hayne’s testimony helped convict Tyler Edmonds, who was just 13 when he falsely confessed that he and his half-sister had both killed her husband. He said she had told him she would “fry,” but he would go unpunished.

At trial, Hayne testified that the fatal wound was consistent with two people pulling the trigger, saying, “I can’t exclude one [shooter], but I think that would be less likely.”

The Mississippi Court of Appeals concluded such testimony was scientifically unfounded: “You cannot look at a bullet wound and tell whether it was made by a bullet fired by one person pulling the trigger or by two persons pulling the trigger simultaneously.”

Diaz said Hayne’s testimony prompted him to dig deeper. “Two hands on a trigger? You don’t have to do any research to know that’s ridiculous,” he said. “That’s what led me to look at Hayne closer.”

What he found was disturbing. He didn’t realize Hayne was essentially acting as state medical examiner, but he wasn’t a board-certified pathologist.

Diaz wound up writing a scathing dissent centered on the pathologist that prompted other justices to change their minds, he said. “As science, like the law, evolves over time, one generation’s expert is another’s quack.”

He now regrets the first vote he cast on the high court, a death penalty case that relied on the words of Hayne and West, he said. “Based upon their testimony, my first Supreme Court vote was to execute an innocent man, Kennedy Brewer.”

He and other justices later supported the dismissal of Brewer’s conviction, and his last opinion called for the end of the death penalty. “It’s not a workable system when errors like this can take place,” he said. “No matter how careful we are, we’re going to vote to execute innocent people.”

What the jury never heard

In November 1993, Statham brought her daughter twice to the hospital for seizures after she stopped breathing. One doctor suggested she could be suffering from Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, a potentially life-threatening reaction, often to medication, that can cause lesions in the mouth and the genital area. The disease can also cause seizures.

Nearly three weeks before her death, a chest of drawers fell on Haley, who suffered three skull fractures and a subdural hematoma that caused her to spend six days in the hospital. Duncan and Statham told child social services that she had been climbing to reach her piggy bank.

But the jury never heard about this serious injury because of a deal that Duncan’s original lawyers made with prosecutors.

Pathologists say it’s critical to know everything possible about a person’s medical history before drawing conclusions about a death. Testimony shows police knew Oliveaux’s medical history, but it remains unclear if Hayne knew that history before concluding she had been raped and killed.

In a six-day hearing last September, two pathologists called Hayne’s conclusions unfounded, said they saw no evidence of a rape or homicide, and believed Haley drowned accidentally, perhaps after suffering a seizure.

In one sworn statement, former jail inmate Michael Lucas said he heard Duncan tell Cruse that he didn’t kill the toddler. An investigator testified that Cruse now admits he lied at the 1998 trial because he wanted leniency for the felony he was facing.

Duncan’s lawyers told those at the hearing that they planned to show West’s video involving Haley, warning that it was graphic and disturbing. An excerpt of that video had first surfaced in 2009 when the Reason website published it. The video appalled many in the legal and forensic science communities.

The video showed West jamming, dragging and scraping Duncan’s dental mold across the child’s body dozens of times. Some of those in the courtroom gasped, some covered their eyes, and others, including Duncan, wiped away tears.

After seeing the video, Lowell Levine, past president of the American Board of Forensic Odontology, called what West did “fraud.”

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences concluded there was no basis in science for forensic odontologists to conclude a person is “the biter” to the exclusion of all other suspects.

Adam Freeman, past president of the American Board of Forensic Odontology, testified that the bite marks identified on Haley weren’t bite marks at all. He called these determinations “junk science” that can’t be defended scientifically.

In 2015, he helped conduct a study on the reliability of bite marks. In all but a few cases, board-certified dentists couldn’t even agree if they were looking at a bite mark. As a result, he resigned from leadership in protest and stopped doing any bite-mark analysis.

Nationwide, at least 34 wrongful convictions have occurred since 1989 because of bite marks, six of them in Mississippi that all involve West, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

Dr. Robert Bux, who served as chief medical examiner for the El Paso County Coroner’s Office in Colorado Springs, questioned how Hayne could say the child’s injuries matched shoving her face underwater.

If that were so, “I’d expect to see injuries on the front part of her body, particularly on her forehead or nose, cheeks, anterior parts of shoulders, anterior parts of the knees,” said Bux, who helped investigate Pat Tillman’s death in Afghanistan.

The autopsy showed lacerations to the anus. Bux said these could have been caused by an infection, a diaper rash, a hard stool or vigorous washing. “There’s no way to know. You have to look at it microscopically, and it wasn’t looked at,” he said.

Up until 2007 or so, people believed anal dilation proved sexual abuse, he said. “A dilated anus means nothing. We saw it all the time in adults and children.”

The lack of blood at the scene suggests something other than a violent assault, he said. “It’s absolutely bloodless. I mean where is the blood in the sink? Where’s the blood on the victim?”

He rejected the claim by Hayne that the child stopped bleeding because she was dead. Blood gives way to gravity, he said. “It’ll come out drip, drip, drip, so, you’re going to see it, and you’re going to see it for hours, and you’re going to see it for days. I don’t think you can just wash that off because it’s going to continue to ooze after she’s dead.”

Her death appears to be “a tragic accident of drowning,” he said. “I don’t see any evidence to me that would support that it was forced.”

She drowned, possibly because she suffered another seizure, he said, “but I can’t prove that because Hayne didn’t do any investigation that would help us on that.”

Hayne’s lack of research and examination prompted Duncan’s lawyers to twice ask for the exhumation of Oliveaux’s body before the 1998 trial. The judge denied the requests.

Her mother said if her daughter’s body needs to be exhumed to answer any questions, she supports that. “It might give us some answers to what happened then,” Statham said.