Mississippi Today

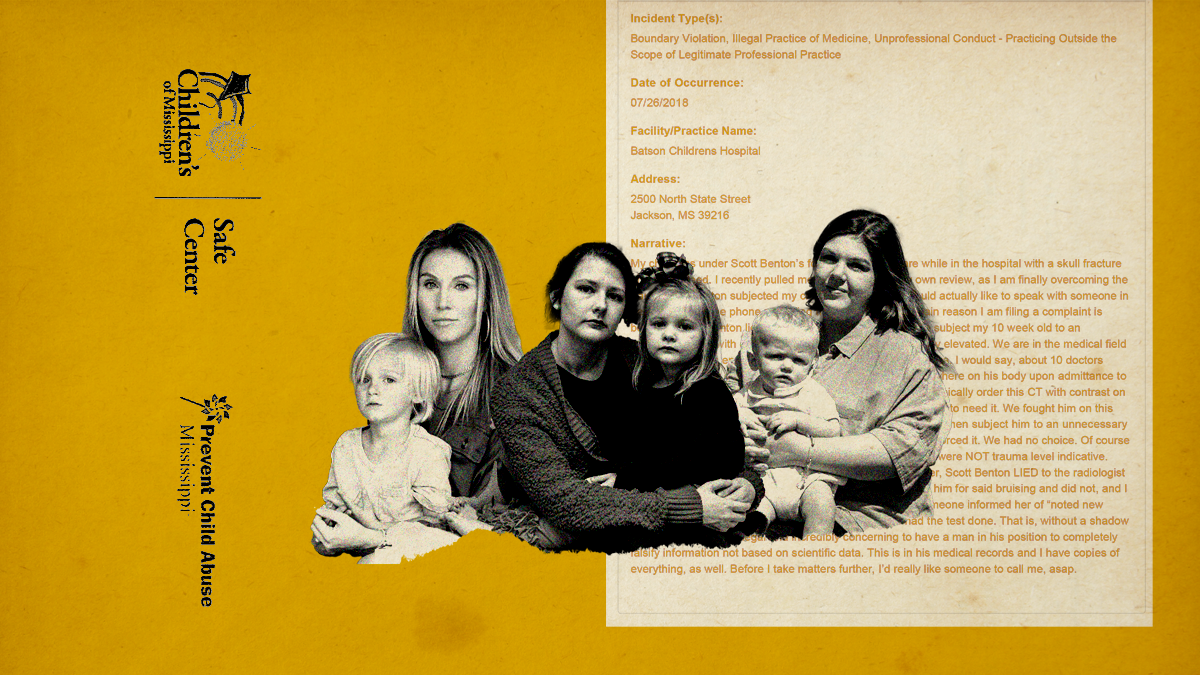

How Dr. Scott Benton’s decisions tore these families apart

How Dr. Scott Benton’s decisions tore these families apart

This story is the third part in Mississippi Today’s “Shaky Science, Fractured Families” investigation about the state’s only child abuse pediatrician crossing the line from medicine into law enforcement and how his decisions can tear families apart.Read the full series here.

Caryn Jordan, Columbia

When Caryn Jordan took her 10-month-old daughter to Forrest General Hospital on March 29, 2020, she never imagined the state would take her child from her.

She said she also never considered that a pediatrician who would accuse her of child abuse wouldn’t do the necessary testing to determine if a genetic disease caused her daughter’s fractures.

The nightmare started when Jordan was putting her daughter Sawyer in her high chair. She noticed one leg was warm and swollen. She tried to get Sawyer to stand up, but the child couldn’t handle pressure being applied to the swollen leg.

At Forrest General Hospital, Jordan said doctors told her an X-ray revealed a fracture on Sawyer’s leg and that the hospital would have to transfer Sawyer to the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) in Jackson because they were not equipped to put a cast on an infant. The hospital had contacted Child Protective Services, she said she later realized.

An official with Forrest General Hospital said when there is suspected abuse or neglect, the hospital social worker is consulted and further screening is done.

“CPS is notified when circumstances warrant,” said Suzanne Wilson, the director of emergency services and transfer center at the hospital.

Wilson said not all suspected abuse cases are transferred out of the facility, but those requiring a specialist’s care are transferred, as well as those in need of pediatric services not provided at the hospital.

After performing a full body X-ray on Sawyer at UMMC, doctors told Jordan her daughter had a broken leg and 11 fractures across her body in various stages of healing.

Jordan was baffled. Sawyer had rarely left their home, aside from frequent doctor visits due to stomach issues and a salmonella infection. Her mind raced for answers.

Then Jordan got a call from Dr. Scott Benton, a pediatrician at UMMC who specializes in child abuse pediatrics. He told her that Sawyer looked like she had been thrown against a wall or in a car accident, she said. Another mother told Mississippi Today that Benton also accused her of throwing her baby against the wall.

“He spoke to me like I was this abusive, disgusting mother,” Jordan said. “I don’t think I’ve ever been that angry.”

Benton, who Jordan said she never saw in person, determined abuse caused her injuries. Jordan said to her knowledge, Benton, who told her on the phone he was out of town at the time, never saw Sawyer in person.

Jordan would not be taking Sawyer home. She was told to leave the hospital, and Sawyer went into the custody of Child Protective Services.

Back home in Columbia, Jordan turned all of her energy into getting Sawyer back, a fight that cost her everything. She was only able to work part time due to frequent court dates and doctor’s visits. She drained her savings and lost her health insurance. Her relationship with her boyfriend imploded. She moved back in with her parents.

“Could the fractures have occurred during birth?” she wondered. At one point, Sawyer got stuck in the birth canal. She had to be pushed back inside and delivered through an emergency cesarean section, Jordan said.

“Might Sawyer have a brittle bone disease called osteogenesis imperfecta?” Jordan thought. The group of inherited genetic disorders affects how the body makes collagen and causes fragile bones. A Facebook group she joined for parents whose children had the disorder encouraged her to request a bone density test.

But when Jordan proposed the idea, Benton replied in text messages that she shared with Mississippi Today: “There is no validated and approved bone density test for infants.”

While bone density tests are not typically performed on infants, there are alternative methods, Jordan said a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital New Orleans told her in June 2020. They include a skin biopsy or genetic testing to look for anomalies in certain genes involved in encoding collagen.

In videos shared with Mississippi Today, the New Orleans doctor tells Jordan that Sawyer’s symptoms and injuries are consistent with what is seen in a child with brittle bone disease, and that often the fractures are painless and left undiscovered for some time.

But Jordan was unaware Benton had performed a genetic osteogenesis imperfecta panel test on Sawyer on March 31, nor was she given the results. That test detected a variant of uncertain significance in her COL1A1 gene, which is involved in collagen production, according to Sawyer’s medical records from UMMC.

Dr. Mahim Jain, director of the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Clinic at Kennedy Krieger Institute and an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said issues with the COL1A1 gene are a major cause of OI.

“A variant of uncertain significance doesn’t really say, ‘Yes, it is disease causing’ or ‘no, it’s not.’ It means that there’s more work to be done to try to sort out if it is causing the condition,” Jain told Mississippi Today.

Benton’s report on Sawyer’s genetic test recommends genetic counseling and targeted testing of her parents to better understand the implications of this variant, but no further testing was done and no explanation was given as to why, according to the medical records.

Jordan said she became aware of the test and its results only after her case was concluded.

Benton declined to answer questions about Jordan and her daughter’s case, even though Jordan submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss her daughter’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

Benton told a group of public defenders in a recorded presentation about sex crimes, however, that before he came to UMMC in 2008, parents and anyone who was suspected of being associated with a child’s injury was “kicked out of the hospital.”

He said he reversed that policy so he could be sure to get a full history from parents and not overlook any possible medical explanations for a child’s injuries.

“That was part of their protocol (at the time). And I said ‘Alright, who am I supposed to get the history from? Who am I supposed to (talk to) to figure out if there’s a medical explanation for some of these bleeding findings?’” he told the group. “So we quickly reversed that.”

For the first three months while Sawyer was with a foster family, Jordan said she wasn’t allowed to see her, despite CPS visitation policy that states contact between the child and his or her parents must be arranged within 72 hours of that child being placed into foster care.

Shannon Warnock, a spokeswoman for CPS, said the agency can’t comment on specific cases, “including any exceptional circumstances that warrant policy adjustments.”

In December 2020, nine months after Jordan went into CPS custody, Jordan’s parents got a foster care license and got custody of Sawyer.

In doing so, that meant Jordan had to move out. She found a one-bedroom apartment she could afford.

Ultimately, the youth court judge concluded Sawyer was abused but it was unclear who inflicted the injuries, so she was returned to Jordan on April 5, 2021.

In the aftermath, Jordan has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, an anxiety disorder and depression. She mourns the milestones she missed during the 15 months Sawyer was taken from her.

“I missed my daughter’s first birthday,” Jordan said. “I missed her first Easter. I missed her first step. I missed a lot of firsts. And these are things I can never get back.”

The separation also affected Sawyer, now an outspoken 3-year-old who sometimes rolls her eyes at her mother and loves to dance.

Sawyer has to carry KeKe, a fuzzy blanket covered in llamas, with her wherever she goes, Jordan said. The baby blanket was the only one of her belongings she was able to keep while in state custody. She still has separation anxiety, and Jordan often has to reassure her she will not leave her again.

Jordan recently scheduled additional testing for Sawyer in New Orleans to confirm if she has the brittle bone disease. She said she waited because of the cost, and because for a long time, the idea of taking Sawyer to a doctor left her terrified.

The two now live in a two-bedroom house in Columbia with a large backyard. They’re trying to start over and create a new normal.

“Ever since they closed our case, I’ve just tried to be a mom,” Jordan said.

Lindsey Tedford, Tupelo

Lindsey Tedford of Tupelo rushed her 3-week-old son Cohen to the local emergency room at North Mississippi Medical Center on June 13, 2021. While her husband was holding their newborn and bent down to pick up a pacifier from the floor, Cohen had hit his head on the nearby crib, the parents told the nurses in the emergency room.

Cohen had bruising under both eyes and on his nose but was otherwise fine, the doctors told her.

The hospital never performed CT or MRI scans, medical records from the visit show.

But when Cohen was at a pediatric cardiologist appointment about two and a half months after the crib accident, the doctor noticed something concerning. Cohen’s head circumference had increased since his two-month checkup with his pediatrician. He scheduled an ultrasound two weeks later, and the results were “concerning for a brain bleed,” according to the baby’s medical records.

The doctor sent them to the North Mississippi Medical Center for a CT scan. It confirmed the ultrasound results: Blood had collected between the skull and the surface of the brain, and Cohen had a possible skull fracture.

The results triggered a chain of events that led to the Tedfords losing custody of Cohen for nearly five months. The state’s only child abuse pediatrician, Dr. Scott Benton, accused them of child abuse and diagnosed Cohen with “nonaccidental trauma.”

In recent months, doctors at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis have diagnosed Cohen, now over a year old, with a bleeding disorder called idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or ITP. Subdural hematomas and intracranial hemorrhage — both diagnoses Cohen received at UMMC — are rare complications of ITP.

Back in September of 2021, the North Mississippi neurosurgeon recommended operating on the brain bleed as soon as possible. Lindsey asked the doctor to transfer Cohen to Le Bonheur in Memphis and left the hospital to go home to get clothes for the trip. On her way back, she got a frantic call from her husband Blake: they had taken Cohen in a helicopter, and he didn’t know where they were taking him, she said.

“As soon as Blake left to go out of the room to follow the people taking Cohen to the helicopter, (people from Child Protective Services) were waiting on him to question him.”

Eventually a nurse manager told him Cohen was sent to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, she said.

A spokeswoman for North Mississippi Medical Center said the hospital aims to care for potential victims of child abuse “with love and respect.”

“We report child abuse to Child Protective Services in accordance with Mississippi regulations and treat as medically appropriate,” the spokeswoman said when asked how the hospital handles cases of suspected abuse and neglect. “UMMC maintains a Pediatric Sub-Specialty Clinic in Tupelo, which offers non-traumatic medical examinations and treatment for cases of suspected abuse and neglect.”

The Tedfords said they made phone calls to UMMC as they drove to Jackson. They eventually found Cohen in the emergency room.

They didn’t hear from Child Protective Services again until almost two weeks later — the day before Cohen was discharged into CPS custody.

CPS policy and state law do not require parents be informed they are being investigated for possible child abuse in any specific time frame.

“The Foster Care Policy manual does say that a parent ‘will be notified prior to, or as soon as safely possible, that his/her child is being placed in custody,’ but there is no specific time period for notifying the parent of the child’s removal,” said Shannon Warnock, a spokesperson for CPS.

She said the agency could not comment on specific cases.

Following more tests, Cohen was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. Neurology, hematology and ophthalmology consulted on his case.

Blood work revealed he was anemic, but medical records note a hematologist “… felt that anemia was most likely secondary to subdural hematoma.”

No other tests or scans were abnormal, according to the records.

About five days into Cohen’s hospital stay, Dr. Scott Benton introduced himself to her and her husband as the “staff forensic pediatrician,” Lindsey said.

“I didn’t know what that meant,” she said. “He said, ‘I’m going to record this session,’ and didn’t tell us a whole lot, just started asking questions.”

The couple relayed how Cohen had hit his head on his crib at 3 weeks old. Benton said the bleeding couldn’t have been caused by that, Lindsey said.

When she showed him pictures of Cohen’s bruised face and the bassinet, he said that didn’t “impress” him, she recalled.

Lindsey also told Benton about Cohen’s “traumatic” birth, but she said he told her the same — it didn’t impress him. During 17 hours of labor, both her and his heart rates dropped on several occasions, and she lost consciousness.

Cohen was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck.

Benton declined to answer questions about Lindsey and her son’s case, even though she submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss her son’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

Lindsey attempted to get the recording of her conversations with Benton from the Children’s Safe Center, the medical center Benton oversees, but was unable to reach an employee, she said. Another mother who attempted to get similar recordings was told she must have an attorney to do so.

At UMMC, a surgeon drilled small openings called burr holes into Cohen’s skull to relieve pressure from the bleeding. He recovered and was discharged from UMMC.

The Tedfords appealed to a CPS case worker to allow Cohen to stay with Blake’s mother, who lived about 20 minutes from their home. CPS tentatively agreed, pending a successful home visit.

On Sept. 22, 2021, officials from Child Protective Services took the baby back to Tupelo. The hospital had diagnosed his injury as “nonaccidental trauma to child.”

For months, the Tedfords’ lives were divided between two houses. CPS had also removed their then-3-year-old daughter Cullen Claire from the home under a safety plan, and she was staying with Lindsey’s parents.

“She kept asking, ‘Why can’t I go home with my mommy and daddy? Is my brother ever going to get better?’ We couldn’t tell her, ‘You can’t come home because these people think we’re abusing you,’” said Lindsey.

Cohen wasn’t sleeping well away from his home, either, and his grandmother was in a state of constant exhaustion.

Over the next several months, CPS visited the Tedfords’ home, and the couple took (and passed) a polygraph test at the end of October, Lindsey said.

At a December safety plan review, Cullen Claire’s court-appointed guardian recommended returning her home because of the detrimental impact on her mental health — contingent on Lindsey receiving a mental evaluation because of the postpartum depression she revealed to Benton at the hospital in their conversation.

Several court dates for Cohen in early January passed with no action from CPS or the prosecution. They finally went back to court at the end of January.

“Our lawyer presented dismissal, saying there was basically not enough evidence to say these people abused their children,” recalled Lindsey. “He said, ‘This has been going on for five months now, nothing’s happened, we haven’t been to trial, and we just now got medical records. How long is this going to go on, and this family is broken?’”

When the judge asked the prosecution if they would be ready for trial in the next month, the attorneys said no.

Cohen’s court-appointed guardian also recommended the child return home. The judge ruled in the Tedfords’ favor, but stated Cohen should remain under a CPS safety plan involving periodic home visits. The plan ended March 2, 2022.

Life for the Tedfords is, on the outside, back to normal. But a lot has changed.

In addition to the health scare with Cohen and frequent trips to Memphis for his doctor appointments for ITP, his sister Cullen Claire, now 4, is struggling.

“We’re looking into child therapy for her. She tells us all the time that she doesn’t think we love her, that no one likes her. She’s struggled at school,” Lindsey said, starting to cry. “It’s definitely caused a lot of trauma.”

Lindsey has also been to therapy to work through what happened.

She said any time there’s a minor accident — bumps, falls and scrapes — she gets worried.

“What would it take for my kids to go back into CPS custody?” she wonders.

Lauren Ayers, Madison

After an afternoon at the playground on July 24, 2018, Lauren Ayers of Madison came home with her 10-week-old twins and almost 2-year-old son.

Ayers’ husband was in Oklahoma for work, so she was left alone with the three boys. She made spaghetti for her older son and herself. After they ate, she started the bedtime routine for the twins, Eli and Conner. She changed Conner’s diaper, swaddled him and laid him in his bassinet in her bedroom.

She put the other twin, Eli, on the plastic diaper changing pad on top of the dresser where she changes the boys’ diapers in their nursery. She had Eli’s onesie undone, so the lower half of his body was pressed directly against the uncovered pad.

The three children’s screams and cries created a cacophony in her home. Eli was kicking and thrashing on the changing pad.

Over the sound of the cries, she heard a clicking noise behind her and turned around, with Eli still on the changing table. Her older son sometimes liked to stand on the glider and rock back and forth, and she’d often have to intercept him before he fell. This time, though, he was playing with a retractable tape measure.

Turning back around, she was horrified to see Eli had scooted himself backwards and had fallen, landing on the crown of his head on the hard floor.

She remembers the resounding thud. When she ran over to pick him up, he was crying, but then became limp and lost consciousness.

“I thought he had broken his neck … I couldn’t find my phone, I was running outside and screaming for anybody to help me,” Ayers recalled. “I finally remembered where my phone was and ran in and called 911. He was unconscious, but he was breathing.”

Ayers’ neighborhood in Flora was new at the time, and she said she was either so upset she wasn’t being clear about where she lived or the emergency response officials weren’t sure where she was. She offered to meet them at Mannsdale Upper Elementary School, about a mile from her house.

“I loaded everybody up, got there … three different fire departments came,” she said. “I kept asking this off-duty firefighter … ‘What do we need to do?’ And he said, ‘Look, if anything’s wrong with him, you want him in the care of an ambulance.’”

With Ayers’ husband out of town and her family in Destin, her best friend came to the school along with her husband.

When no ambulance had arrived 30 minutes later, “the off-duty firefighter was like, ‘You’ve got to get him to a hospital,’” she said. “So my best friend’s husband drove us (to the University of Mississippi Medical Center).”

Ayers’ friend stayed with her and Eli, who had regained consciousness, when he arrived in the emergency room.Two of Ayers’ other friends were also in the emergency room with them, along with her in-laws.

“Thank God people could come back in the ER (because) they were witnesses of everything that happened … They tried to get an IV in him … They stuck him probably over 12 times,” Ayers described. “They couldn’t get blood from him.”

The nurses started a procedure called “milking,” said Ayers, where they would put both hands on Eli’s legs and arms and squeeze the skin in opposite directions in an attempt to get blood to flow.

They checked his stats, ran tests and admitted him to the pediatric intensive care unit for the night. A neurosurgeon reassured Ayers and her family that while the injury was bad, Eli would recover.

A scan the next morning showed Eli’s brain bleed had not gotten any larger, so he was moved to a regular room. That day, Ayers said the nurse told her the forensic pediatrician wanted to go over what happened. Ayers had no idea what a forensic pediatrician was.

Ayers attempted to get a recording of her conversation with Benton to share with Mississippi Today, but was told by the Children’s Safe Center, the medical center Benton oversees, that she would have to get an attorney to obtain it.

But she well remembers how the conversation began.

“He goes on to explain his (Eli’s) injuries and then asked if I remembered (the actress) Natasha Richardson. And I was like ‘Yea, yea, from the ‘Parent Trap’,’” she said. “And he goes, you know, ‘she had the skiing accident … This is the same injury your child has.’”

Richardson suffered a head injury and died two days later in 2009.

Ayers was shocked. She thought maybe Benton was about to tell her something was very wrong.

Benton abruptly closed his notebook and looked at her, she said.

“He said, ‘You’re under a lot of pressure right now. You have three kids, you were home alone — postpartum (depression) is a real thing,’” she remembered. “‘Tell me what really happened.”

Benton’s notes from Eli’s medical records show his certainty that the baby was not injured the way Ayers said.

“The fractures are discontinuous (do not connect) and appear to represent separate impact sites,” his notes show. “… Bilateral fractures are not reported in single fall incidents except where the skull fractures are continuous across sutures or in cases of bilateral out bending from a posterior impact causing symmetrical fractures.”

He goes on to note his concerns are whether Eli was developmentally able to kick or slide himself backwards and whether his skull fractures are “consistent” with Ayers’ account of what happened.

An occupational therapist who later evaluated Eli noted he was “quite active for age and may be slightly ahead with developmental milestones.” Ayers also took a video of Eli scooting himself backwards off a diaper changing pad, which she provided to Mississippi Today. In the video, he is wearing the same onesie outfit he was wearing in photos from the hospital.

She said Benton then told her he believes she threw the baby against a wall.

Yet the “most traumatizing part” of the first meeting with Benton, she said, was when he “strips that baby naked, and he’s looking, I guess, for signs of abuse.”

He started taking pictures of the bruises and needle marks from when Eli was admitted in the ER. Ayers asked what he was doing, and he said he believed she had inflicted the bruises.

He argued with her that the bruises were not from attempts to draw blood, and that “milking” was against hospital policy.

“I kept saying, ‘Don’t you see the needle marks?’ I was screaming at the nurses, ‘These are needle marks, you see them and you gave them to him!’” said Ayers.

Her friend had written down the names of the nurses who treated Eli in the emergency room, and Ayers begged Benton to talk to them. Ayers found a nurse who showed Benton records that when Eli first came to the hospital, no bruising or marks were noted.

A pediatric general surgeon who reviewed Eli two days later noted “bruising to left hand with visible venous access attempt noted” and “IV to right foot.”

Benton backed off, she said. But Ayers’ anxiety had only increased.

“At that point I was like, ‘They’re going to take this baby from me,’” she said.

Benton declined to answer questions about Ayers and her son’s case, even though Ayers submitted a form to UMMC authorizing hospital employees to discuss Eli’s medical records with Mississippi Today.

At the next meeting with Benton, Ayers had family members with her, including her father-in-law, a pharmacist. One of Eli’s tests had come back showing he had slightly elevated liver enzymes, which Benton believed indicated trauma to the abdomen.

Ayers’ father-in-law asked to review the test results.

“He (my father-in-law) literally looked at him and said, ‘Dr. Benton, with all due respect, these are stress-related elevated enzymes,’” she recalled. “‘These are not trauma-level numbers.’”

Benton said Eli would need to do a CT with contrast that requires fasting and radiation. Radiation exposure is particularly concerning in children because they are more sensitive to radiation. And because they have a longer life expectancy than adults, that results in a larger window of opportunity for them to experience radiation damage.

Ayers and her father-in-law objected to the CT, noting Ayers’ husband, Drew, had a kidney condition that made dehydration particularly dangerous, and there was a chance Eli might have the same issue.

But Benton insisted, and they relented.

In the paperwork under “clinical history” for the CT scan, it states: “Reported new bruising on the abdomen. Concern for blunt trauma to abdomen.” There had never been any mention of abdominal bruising in the medical records or to Ayers up until that point, and the CT was performed two days after Eli came to the hospital.

The scan came back normal.

“No evidence of blunt trauma to the abdomen. No acute fractures or dislocations,” the report stated.

Eli was discharged but subjected to another full body X-ray several weeks after he left, according to records. A case worker from Child Protective Services visited Ayers’ home and cleared Eli to return. Several weeks later, a Madison County sheriff’s investigator also interviewed Ayers.

The case was closed that day, the incident report stated.

What haunts Ayers even four years later is wondering what happens to mothers without the resources she had: the ability to hire an attorney, a family member in the medical field to sit in on meetings with Benton and the support of friends and family who were in the emergency room and hospital with her.

“This man should have some more oversight … if you’re going to subject a 10-week-old to all these tests, two MRIs, a CT, X-rays, you should have your evidence in order,” said Ayers, who said she struggled “with some pretty dark days” after the accusations from Benton and the experience in the hospital.

Ayers filed a complaint with the Mississippi State Board of Medical Licensure in March of last year. In her complaint, she highlighted the unexplained “new bruising to abdomen” on the notes for his CT – bruising that was never mentioned anywhere else in his medical records.

“I would say, about 10 doctors signed off that my child (the patient) had ZERO bruising anywhere on his body upon admittance to the hospital … Scott Benton couldn’t ethically order this CT with contrast on my child bc (because) his liver enzymes weren’t actually elevated enough to need it,” she wrote. “ … Before I take matters further, I’d really like someone to call me, asap.”

She never heard anything back.

Editor’s note: Kate Royals, Mississippi Today’s community health editor since January 2022, worked as a writer/editor for UMMC’s Office of Communications from November 2018 through August 2020, writing press releases and features about the medical center’s schools of dentistry and nursing.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=210275

Mississippi Today

Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing

TYLERTOWN — As an ominous storm approached Buddy Anthony’s one-story brick home, he took shelter in his new Ford F-250 pickup parked under a nearby carport.

Seconds later, a tornado tore apart Anthony’s home and damaged the truck while lifting it partly in the air. Anthony emerged unhurt. But he had to replace his vehicle with a used truck that became his home while waiting for President Donald Trump to issue a major disaster declaration so that federal money would be freed for individuals reeling from loss. That took weeks.

“You wake up in the truck and look out the windshield and see nothing. That’s hard. That’s hard to swallow,” Anthony said.

Disaster survivors are having to wait longer to get aid from the federal government, according to a new Associated Press analysis of decades of data. On average, it took less than two weeks for a governor’s request for a presidential disaster declaration to be granted in the 1990s and early 2000s. That rose to about three weeks during the past decade under presidents from both major parties. It’s taking more than a month, on average, during Trump’s current term, the AP found.

The delays mean individuals must wait to receive federal aid for daily living expenses, temporary lodging and home repairs. Delays in disaster declarations also can hamper recovery efforts by local officials uncertain whether they will receive federal reimbursement for cleaning up debris and rebuilding infrastructure. The AP collaborated with Mississippi Today and Mississippi Free Press on the effects of these delays for this report.

“The message that I get in the delay, particularly for the individual assistance, is that the federal government has turned its back on its own people,” said Bob Griffin, dean of the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity at the University at Albany in New York. “It’s a fundamental shift in the position of this country.”

The wait for disaster aid has grown as Trump remakes government

The Federal Emergency Management Agency often consults immediately with communities to coordinate their initial disaster response. But direct payments to individuals, nonprofits and local governments must wait for a major disaster declaration from the president, who first must receive a request from a state, territory or tribe. Major disaster declarations are intended only for the most damaging events that are beyond the resources of states and local governments.

Trump has approved more than two dozen major disaster declarations since taking office in January, with an average wait of almost 34 days after a request. That ranged from a one-day turnaround after July’s deadly flash flooding in Texas to a 67-day wait after a request for aid because of a Michigan ice storm. The average wait is up from a 24-day delay during his first term and is nearly four times as long as the average for former Republican President George H.W. Bush, whose term from 1989-1993 coincided with the implementation of a new federal law setting parameters for disaster determinations.

The delays have grown over time, regardless of the party in power. Former Democratic President Joe Biden, in his last year in office, averaged 26 days to declare major disasters — longer than any year under former Democratic President Barack Obama.

FEMA did not respond to the AP’s questions about what factors are contributing to the trend.

Others familiar with FEMA noted that its process for assessing and documenting natural disasters has become more complex over time. Disasters have also become more frequent and intense because of climate change, which is mostly caused by the burning of fuels such as gas, coal and oil.

The wait for disaster declarations has spiked as Trump’s administration undertakes an ambitious makeover of the federal government that has shed thousands of workers and reexamined the role of FEMA. A recently published letter from current and former FEMA employees warned the cuts could become debilitating if faced with a large-enough disaster. The letter also lamented that the Trump administration has stopped maintaining or removed long-term planning tools focused on extreme weather and disasters.

Shortly after taking office, Trump floated the idea of “getting rid” of FEMA, asserting: “It’s very bureaucratic, and it’s very slow.”

FEMA’s acting chief suggested more recently that states should shoulder more responsibility for disaster recovery, though FEMA thus far has continued to cover three-fourths of the costs of public assistance to local governments, as required under federal law. FEMA pays the full cost of its individual assistance.

Former FEMA Administrator Pete Gaynor, who served during Trump’s first term, said the delay in issuing major disaster declarations likely is related to a renewed focus on making sure the federal government isn’t paying for things state and local governments could handle.

“I think they’re probably giving those requests more scrutiny,” Gaynor said. “And I think it’s probably the right thing to do, because I think the (disaster) declaration process has become the ‘easy button’ for states.”

The Associated Press on Monday received a statement from White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson in response to a question about why it is taking longer to issue major natural disaster declarations:

“President Trump provides a more thorough review of disaster declaration requests than any Administration has before him. Gone are the days of rubber stamping FEMA recommendations – that’s not a bug, that’s a feature. Under prior Administrations, FEMA’s outsized role created a bloated bureaucracy that disincentivized state investment in their own resilience. President Trump is committed to right-sizing the Federal government while empowering state and local governments by enabling them to better understand, plan for, and ultimately address the needs of their citizens. The Trump Administration has expeditiously provided assistance to disasters while ensuring taxpayer dollars are spent wisely to supplement state actions, not replace them.”

In Mississippi, frustration festered during wait for aid

The tornado that struck Anthony’s home in rural Tylertown on March 15 packed winds up to 140 mph. It was part of a powerful system that wrecked homes, businesses and lives across multiple states.

Mississippi’s governor requested a federal disaster declaration on April 1. Trump granted that request 50 days later, on May 21, while approving aid for both individuals and public entities.

On that same day, Trump also approved eight other major disaster declarations for storms, floods or fires in seven other states. In most cases, more than a month had passed since the request and about two months since the date of those disasters.

If a presidential declaration and federal money had come sooner, Anthony said he wouldn’t have needed to spend weeks sleeping in a truck before he could afford to rent the trailer where he is now living. His house was uninsured, Anthony said, and FEMA eventually gave him $30,000.

In nearby Jayess in Lawrence County, Dana Grimes had insurance but not enough to cover the full value of her damaged home. After the eventual federal declaration, Grimes said FEMA provided about $750 for emergency expenses, but she is now waiting for the agency to determine whether she can receive more.

“We couldn’t figure out why the president took so long to help people in this country,” Grimes said. “I just want to tie up strings and move on. But FEMA — I’m still fooling with FEMA.”

Jonathan Young said he gave up on applying for FEMA aid after the Tylertown tornado killed his 7-year-old son and destroyed their home. The process seemed too difficult, and federal officials wanted paperwork he didn’t have, Young said. He made ends meet by working for those cleaning up from the storm.

“It’s a therapy for me,” Young said, “to pick up the debris that took my son away from me.”

Historically, presidential disaster declarations containing individual assistance have been approved more quickly than those providing assistance only to public entities, according to the AP’s analysis. That remains the case under Trump, though declarations for both types are taking longer.

About half the major disaster declarations approved by Trump this year have included individual assistance.

Some people whose homes are damaged turn to shelters hosted by churches or local nonprofit organizations in the initial chaotic days after a disaster. Others stay with friends or family or go to a hotel, if they can afford it.

But some insist on staying in damaged homes, even if they are unsafe, said Chris Smith, who administered FEMA’s individual assistance division under three presidents from 2015-2022. If homes aren’t repaired properly, mold can grow, compounding the recovery challenges.

That’s why it’s critical for FEMA’s individual assistance to get approved quickly — ideally, within two weeks of a disaster, said Smith, who’s now a disaster consultant for governments and companies.

“You want to keep the people where they are living. You want to ensure those communities are going to continue to be viable and recover,” Smith said. “And the earlier that individual assistance can be delivered … the earlier recovery can start.”

In the periods waiting for declarations, the pressure falls on local officials and volunteers to care for victims and distribute supplies.

In Walthall County, where Tylertown is, insurance agent Les Lampton remembered watching the weather news as the first tornado missed his house by just an eighth of a mile. Lampton, who moonlights as a volunteer firefighter, navigated the collapsed trees in his yard and jumped into action. About 45 minutes later, the second tornado hit just a mile away.

“It was just chaos from there on out,” Lampton said.

Walthall County, with a population of about 14,000, hasn’t had a working tornado siren in about 30 years, Lampton said. He added there isn’t a public safe room in the area, although a lot of residents have ones in their home.

Rural areas with limited resources are hit hard by delays in receiving funds through FEMA’s public assistance program, which, unlike individual assistance, only reimburses local entities after their bills are paid. Long waits can stoke uncertainty and lead cost-conscious local officials to pause or scale-back their recovery efforts.

In Walthall County, officials initially spent about $700,000 cleaning up debris, then suspended the cleanup for more than a month because they couldn’t afford to spend more without assurance they would receive federal reimbursement, said county emergency manager Royce McKee. Meanwhile, rubble from splintered trees and shattered homes remained piled along the roadside, creating unsafe obstacles for motorists and habitat for snakes and rodents.

When it received the federal declaration, Walthall County took out a multimillion-dollar loan to pay contractors to resume the cleanup.

“We’re going to pay interest and pay that money back until FEMA pays us,” said Byran Martin, an elected county supervisor. “We’re hopeful that we’ll get some money by the first of the year, but people are telling us that it could be [longer].”

Lampton, who took after his father when he joined the volunteer firefighters 40 years ago, lauded the support of outside groups such as Cajun Navy, Eight Days of Hope, Samaritan’s Purse and others. That’s not to mention the neighbors who brought their own skid steers and power saws to help clear trees and other debris, he added.

“That’s the only thing that got us through this storm, neighbors helping neighbors,” Lampton said. “If we waited on the government, we were going to be in bad shape.”

Lieb reported from Jefferson City, Missouri, and Wildeman from Hartford, Connecticut.

Update 98/25: This story has been updated to include a White House statement released after publication.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical view of the Trump administration’s handling of disaster declarations, highlighting delays and their negative impacts on affected individuals and communities. It emphasizes concerns about government downsizing and reduced federal support, themes often associated with center-left perspectives that favor robust government intervention and social safety nets. However, it also includes statements from Trump administration officials defending their approach, providing some balance. Overall, the tone and framing lean slightly left of center without being overtly partisan.

Mississippi Today

Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina

The 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina slamming the Mississippi Gulf Coast has come and gone, rightfully garnering considerable media attention.

But still undercovered in the 20th anniversary saga of the storm that made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, and caused unprecedented destruction is the role that a worm farmer from northeast Mississippi played in helping to revitalize the Coast.

House Speaker Billy McCoy, who died in 2019, was a worm farmer from the Prentiss, not Alcorn County, side of Rienzi — about as far away from the Gulf Coast as one could be in Mississippi.

McCoy grew other crops, but a staple of his operations was worm farming.

Early after the storm, the House speaker made a point of touring the Coast and visiting as many of the House members who lived on the Coast as he could to check on them.

But it was his action in the forum he loved the most — the Mississippi House — that is credited with being key to the Coast’s recovery.

Gov. Haley Barbour had called a special session about a month after the storm to take up multiple issues related to Katrina and the Gulf Coast’s survival and revitalization. The issue that received the most attention was Barbour’s proposal to remove the requirement that the casinos on the Coast be floating in the Mississippi Sound.

Katrina wreaked havoc on the floating casinos, and many operators said they would not rebuild if their casinos had to be in the Gulf waters. That was a crucial issue since the casinos were a major economic engine on the Coast, employing an estimated 30,000 in direct and indirect jobs.

It is difficult to fathom now the controversy surrounding Barbour’s proposal to allow the casinos to locate on land next to the water. Mississippi’s casino industry that was birthed with the early 1990s legislation was still new and controversial.

Various religious groups and others had continued to fight and oppose the casino industry and had made opposition to the expansion of gambling a priority.

Opposition to casinos and expansion of casinos was believed to be especially strong in rural areas, like those found in McCoy’s beloved northeast Mississippi. It was many of those rural areas that were the homes to rural white Democrats — now all but extinct in the Legislature but at the time still a force in the House.

So, voting in favor of casino expansion had the potential of being costly for what was McCoy’s base of power: the rural white Democrats.

Couple that with the fact that the Democratic-controlled House had been at odds with the Republican Barbour on multiple issues ranging from education funding to health care since Barbour was inaugurated in January 2004.

Barbour set records for the number of special sessions called by the governor. Those special sessions often were called to try to force the Democratic-controlled House to pass legislation it killed during the regular session.

The September 2005 special session was Barbour’s fifth of the year. For context, current Gov. Tate Reeves has called four in his nearly six years as governor.

There was little reason to expect McCoy to do Barbour’s bidding and lead the effort in the Legislature to pass his most controversial proposal: expanding casino gambling.

But when Barbour ally Lt. Gov. Amy Tuck, who presided over the Senate, refused to take up the controversial bill, Barbour was forced to turn to McCoy.

The former governor wrote about the circumstances in an essay he penned on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina for Mississippi Today Ideas.

“The Senate leadership, all Republicans, did not want to go first in passing the onshore casino law,” Barbour wrote. “So, I had to ask Speaker McCoy to allow it to come to the House floor and pass. He realized he should put the Coast and the state’s interests first. He did so, and the bill passed 61-53, with McCoy voting no.

“I will always admire Speaker McCoy, often my nemesis, for his integrity in putting the state first.”

Incidentally, former Rep. Bill Miles of Fulton, also in northeast Mississippi, was tasked by McCoy with counting, not whipping votes, to see if there was enough support in the House to pass the proposal. Not soon before the key vote, Miles said years later, he went to McCoy and told him there were more than enough votes to pass the legislation so he was voting no and broached the idea of the speaker also voting no.

It is likely that McCoy would have voted for the bill if his vote was needed.

Despite his no vote, the Biloxi Sun Herald newspaper ran a large photo of McCoy and hailed the Rienzi worm farmer as a hero for the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a factual and balanced account of the political dynamics surrounding Hurricane Katrina recovery efforts in Mississippi, focusing on bipartisan cooperation between Democratic and Republican leaders. It highlights the complexities of legislative decisions without overtly favoring one party or ideology, reflecting a neutral and informative tone typical of centrist reporting.

Mississippi Today

PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership

NEW ALBANY — After five hours in a courtroom where attendees struggled to find standing room, the Mississippi Public Service Commission voted to petition a judge to put the Holly Springs Utility Department into a receivership.

The PSC held the hearing Thursday about a half hour drive west from Holly Springs in New Albany, known as “The Fair and Friendly City.” Throughout the proceedings, members of the PSC, its consultants and Holly Springs officials emphasized there was no precedent for what was going on.

The city of Holly Springs has provided electricity through a contract with the Tennessee Valley Authority since 1935. It serves about 12,000 customers, most of whom live outside the city limits. While current and past city officials say the utility’s issues are a result of financial negligence over many years, the service failures hit a boiling point during a 2023 ice storm where customers saw outages that lasted roughly two weeks as well as power surges that broke their appliances.

Those living in the service area say those issues still occur periodically, in addition to infrequent and inaccurate billing.

“I moved to Marshall County in 2020 as a place for retirement for my husband and I, and it’s been a nightmare for five years,” customer Monica Wright told the PSC at Thursday’s hearing. “We’ve replaced every electronic device we own, every appliance, our well pump and our septic pumps. It has financially broke us.

“We’re living on prayers and promises, and we need your help today.”

Another customer, Roscoe Sitgger of Michigan City, said he recently received a series of monthly bills between $500 and $600.

Following a scathing July report by Silverpoint Consulting that found Holly Springs is “incapable” of running the utility, the three-member PSC voted unanimously on Thursday to determine the city isn’t providing “reasonably adequate service” to its customers. That language comes from a 2024 state bill that gave the commission authority to investigate the utility.

The bill gives a pathway for temporarily removing the utility’s control from the city, allowing the PSC to petition a chancery judge to place the department into the hands of a third party. The PSC voted unanimously to do just that.

Thursday’s hearing gave the commission its first chance to direct official questions at Holly Springs representatives. Newly elected Mayor Charles Terry, utility General Manager Wayne Jones and City Attorney John Keith Perry fielded an array of criticism from the PSC. In his rebuttal, Perry suggested that any solution — whether a receivership or selling the utility — would take time to implement, and requested 24 months for the city to make incremental improvements. Audience members shouted, “No!” as Perry spoke.

“We are in a crisis now,” responded Northern District Public Service Commissioner Chris Brown. “To try to turn the corner in incremental steps is going to be almost impossible.”

It’s unclear how much it would cost to fix the department’s long list of ailments. In 2023, TVPPA — a nonprofit that represents TVA’s local partners — estimated Holly Springs needs over $10 million just to restore its rights-of-way, and as much as $15 million to fix its substations. The department owes another $10 million in debt to TVA as well as its contractors, Brown said.

“The city is holding back the growth of the county,” said Republican Sen. Neil Whaley of Potts Camp, who passionately criticized the Holly Springs officials sitting a few feet away. “You’ve got to do better, you’ve got to realize you’re holding these people hostage, and it’s not right and it’s not fair… They are being represented by people who do not care about them as long as the bill is paid.”

In determining next steps, Silverpoint Principal Stephanie Vavro told the PSC it may be hard to find someone willing to serve as receiver for the utility department, make significant investments and then hand the keys back to the city. The 2024 bill, Vavro said, doesn’t limit options to a receivership, and alternatives could include condemning the utility or finding a nearby utility to buy the service area.

Answering questions from Central District Public Service Commissioner De’Keither Stamps, Vavro said it’s unclear how much the department is worth, adding an engineer’s study would be needed to come up with a number.

Terry, who reminded the PSC he’s only been Holly Springs’ mayor for just over 60 days, said there’s no way the city can afford the repair costs on its own. The city’s median income is about $47,000, roughly $8,000 less than the state’s as a whole.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a factual and balanced account of the situation involving the Holly Springs Utility Department and the Mississippi Public Service Commission. It includes perspectives from various stakeholders, such as city officials, residents, and state commissioners, without showing clear favoritism or ideological slant. The focus is on the practical challenges and financial issues faced by the utility, reflecting a neutral stance aimed at informing readers rather than advocating a particular political viewpoint.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

‘One Pill Can Kill’ program aims to reduce opioid drug overdose

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Alabama lawmaker revives bill to allow chaplains in public schools

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Arkansas’s morning headlines | Sept. 9, 2025

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

‘Resilience and hope’ in Galveston: 125 years after greatest storm in US history | Texas

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Pulaski County town faces scrutiny after fatal overdose

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed7 days ago

Man tries to save driver in deadly I-85 crash | FOX 5 News

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

Mississippi News Video6 days ago

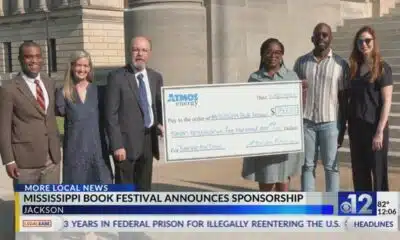

2025 Mississippi Book Festival announces sponsorship