Mississippi Today

For this Delta State student with autism, ‘there’s always another wall to climb with no ladder’

For this Delta State student with autism, ‘there’s always another wall to climb with no ladder’

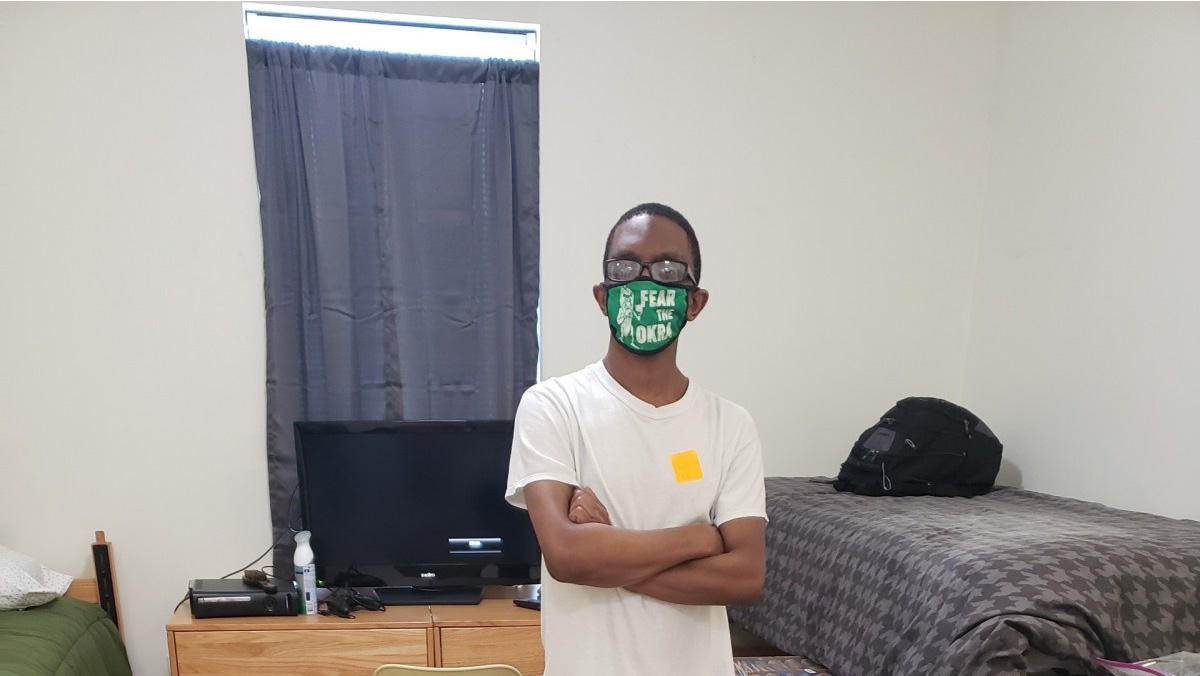

CLEVELAND — On a recent Thursday afternoon, Avery Williams hurried down an empty hallway in Kethley Hall with his mother, Deloris-Clay Williams. The 25-year-old was looking for a room he’d never been in before where, in less than five minutes, a meeting was scheduled to start that would determine the fate of his academic future at Delta State University.

His mother eventually found the sign, stamped on a window in sharp, black letters, that signaled they were in the right place: “College of Arts and Sciences — Office of the Dean.”

This was supposed to be Avery’s last semester. Avery has autism, a developmental disability that affects communication and learning, and he enrolled at Delta State two and a half years ago after getting his associate degree from the community college in his hometown of Moorhead.

By going away to college, Avery hoped to achieve two dreams: Become a cinematographer or video editor, and learn to live on his own. Deloris, who has lupus, was increasingly finding it harder to assist him.

But in the midst of the pandemic, Avery struggled to communicate with his professors via message board. His GPA steadily dropped. Over winter break, he was suspended. Nobody told him in person. All he got was an email.

Now he wouldn’t be able to graduate with the art degree he’d worked so hard for, and had taken out more than $30,000 in student loans to get.

Avery’s struggle to get through DSU is just one example of how universities in Mississippi are failing students with autism. While one state agency offers peer mentoring services, only one public university in Mississippi has an in-house program designed for students with autism. And there is no comprehensive data on the rate at which students with disabilities, including those with autism, enroll and graduate from college in Mississippi.

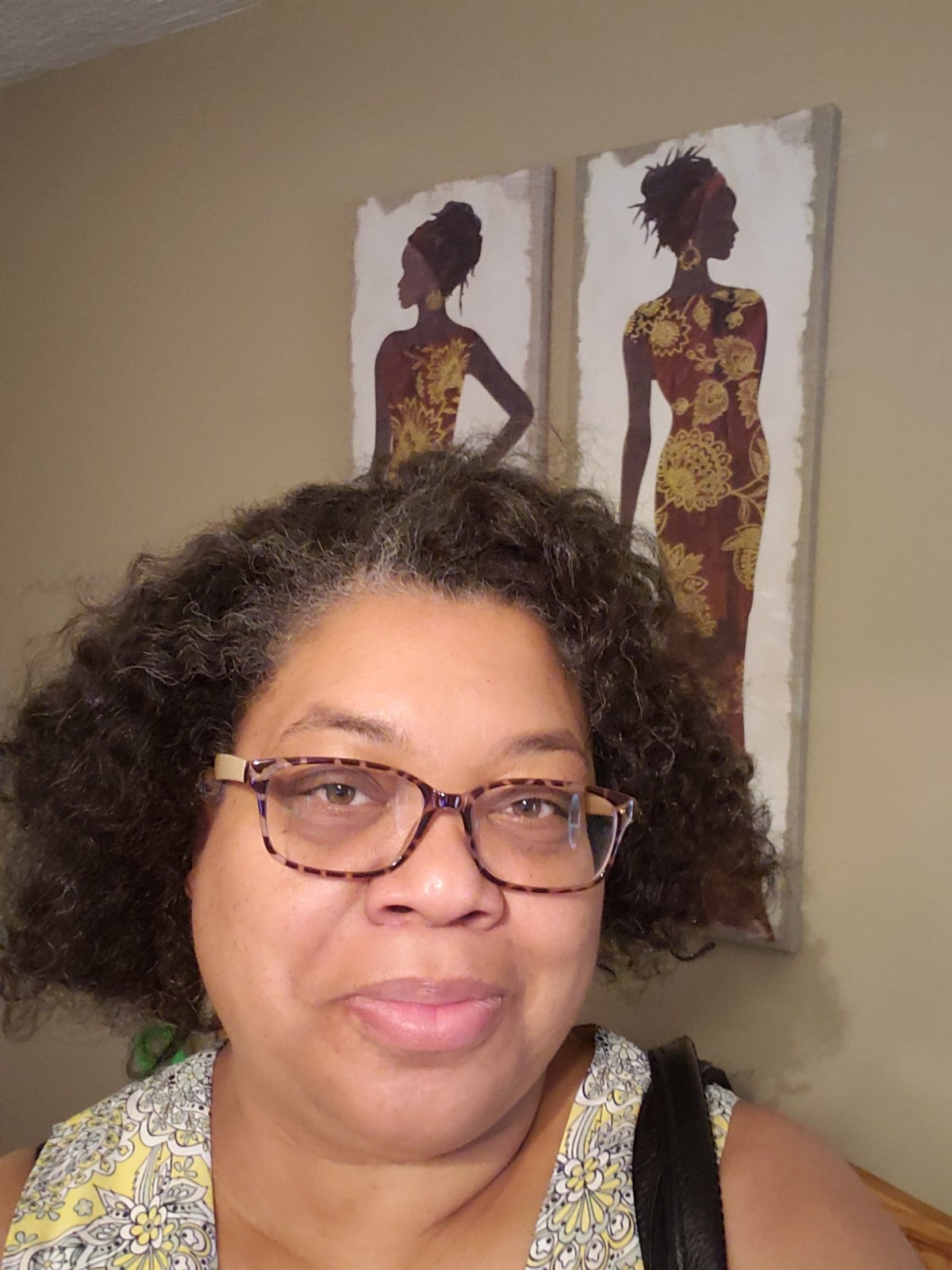

What was happening to Avery didn’t seem fair to Deloris. She decided to intervene. A retired public school teacher trained at DSU, she was used to standing up for Avery’s right to an education. It’d just been awhile since she’d had to do so.

On Jan. 9, the first day of classes, Deloris sent the dean, Ellen Green, a fiery email requesting Avery be readmitted to the art program. She signed it, “desperate parent.”

It got Avery a meeting. In the waiting room outside the dean’s office, Deloris looked over questions she’d prepared in a comprehensive notebook. Avery stood silently in the middle of the room, his arms crossed, anxious to know if he would be able to re-enroll and take classes. He just wanted to get the meeting over with.

At 4 years old, Avery could read, write his first and last name, and count to 100. He’d also cry at the sight of hair on the floor. If Deloris gave him a pencil and paper, she said he would draw circles “over and over.” The only food he’d eat was chicken nuggets.

Then he got encephalitis. It led to memory loss and intensified his repetitive behaviors. By the time Avery started elementary school, Deloris was certain he had autism. He was quiet and avoided playing with other kids unless it was basketball with his younger brother, Alex Williams.

Though Deloris begged Avery’s teachers to test him for autism, they wouldn’t. He wasn’t tested for any learning disabilities until fifth grade and only after Deloris said she wrote a complaint to MDE’s Office of Special Education.

That experience taught Deloris how to advocate for Avery, but it also foreshadowed just how much time and effort it would take to bend Mississippi’s school system in his favor.

It also set up a pattern that Deloris learned to expect any time she spoke up for Avery: Besting one hurdle usually brought another. Despite Deloris’s certainty, the first doctor to test Avery diagnosed him with an unspecified learning disability, not autism. Avery wouldn’t be diagnosed with autism until he was 15.

This is a common experience for Black children with autism. A 2007 study showed that at their first visit, Black children were 2.6 times less likely to be diagnosed than white children. ADHD was instead the most common diagnosis. As a result, they tend to receive treatment later in childhood when it’s less likely to be effective.

“As a parent, I have felt like I have failed him so many times,” Deloris said. “No matter how hard I work, it’s like there’s always another wall to climb with no ladder, so you gotta find a way around it, through it, over it — without help.”

Avery’s elementary school was down the road from Deloris’ house, right next to the levy his granddad helped build. She could keep a close eye on him. But middle school was another matter.

Deloris didn’t want to send Avery to the public junior high — it had a reputation for fighting. Instead, she enrolled him in a nearby private religious academy.

“It was supposed to be like a Christian school,” she said.

Avery said he was ignored by the teacher unless he did something wrong, like peeking at the answer key for tests, even if other kids did the same thing. This, too, is a regular experience for Black students with disabilities. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs, they’re more likely to be disciplined than their peers.

Toward the end of the 2014 school year, Avery and his brother were waiting outside when another student said the teacher wanted to see him.

“When he said that, I felt like something wasn’t right about this,” Avery said. “But I would just respect my teachers anyway, so I just went, despite the feeling.”

A second teacher came into the room and used a paddle on Avery while his teacher watched.

“I had no idea what was going on,” Avery said. “There was no explanation.”

When Deloris picked the boys up from school, she said that Avery, who never cries, was so angry he had tears streaming down his face.

They never went back to that school. But to this day, the experience shaped how Avery communicates with his teachers.

In summer 2020, Avery sat at Deloris’ kitchen table. Together they wrote a list of six accommodations they hoped he’d get at DSU that fall, including “extended time on projects/tests” and “daily life assistance with rules/ activities.”

Accommodations like these helped Avery get his associate degree at Mississippi Delta Community College.

With extra time for assignments, Avery went to MDCC’s tutoring center every day, braving rain and a neighbor’s pack of loud dogs. Algebra was his toughest subject, but with a tutor’s help, Avery was showing his classmates how to solve problems.

But when he got to DSU, the only accommodation Avery received was extended time on tests, according to a fall 2020 letter from the university.

This is not unusual. The laws that govern disability services in college — the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 — are less extensive than those in K-12. Administrators have latitude to decline accommodations that would “fundamentally alter” a course or pose an undue financial burden to the university.

That fall, the university did not have a dedicated disability coordinator, according to budget documents. Kashanta Jackson, the director of the Office of Health and Counseling Services, filled the role until August last year when it became its own position.

In recent years, anywhere from just 14 students to 60 have requested accommodations each semester, according to a records request.

Jackson told Mississippi Today that since she started at DSU in early 2020, her office has never denied a student’s request for accommodation, though she signed the letter granting only one to Avery.

Deloris said, in retrospect, the partial denial was a sign that her alma mater might not be the place for Avery. It also bothered her that when she asked why Avery only received one accommodation, the university said his request was private under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

If Deloris wanted to talk to the school on Avery’s behalf, he’d have to sign a waiver.

FERPA is intended to protect students’ privacy, but for parents of students with disabilities, it can be a barrier, said Jerry Alliston, the assistant director of the University of Southern Mississippi’s Institute for Disability Studies.

It made Deloris feel like she wasn’t supposed to step in for Avery. But she knew that no one else on campus was advocating for him.

One incident at the end of Avery’s first fall semester demonstrated Deloris’ worry. The day she picked Avery up from his dorm, she went to his bathroom when he exclaimed, “don’t turn the light on!”

There was water dripping from the ceiling — it had been almost the whole semester. Avery didn’t know how he was supposed to request a fix because no one had shown him where to go.

DSU has been candid in the past about its shortcomings serving students with disabilities.

“I’m not saying students with disabilities shouldn’t come to DSU, but if accommodations are their priority, then they should look at universities that are able to be equipped to accommodate them,” Dr. Richard Houston, the former director of counseling, told the student newspaper in 2019.

Four years later, there’s still little programming and no clubs for students with disabilities. Disability Services mainly approves accommodations and relays students’ requests to their professors. But it doesn’t track the outcomes of the students it serves, according to a records request, such as if they graduated or not.

Jackson said she hopes to grow DSU’s services but that “it’s kind of hard to say what we’re gonna get more of without knowing specifically what students we’re going to have.” While funding is a limiting factor, she said her office is “doing pretty well with what we have.”

It’s not just DSU. The entire state of Mississippi is behind when it comes to serving students with disabilities. The state Department of Rehabilitation Services funds peer mentoring programs for students with disabilities in Mississippi, Alliston said, but just two universities – University of Southern Mississippi and Mississippi State University – have taken the offer. And MSU is the only university in the state with a case management program for students with autism.

Avery almost went to MSU, but it was too far away. A peer mentoring program would have benefited him, particularly with talking to professors. He’d email them a question about an assignment, only to be told to check the syllabus, which he had read and didn’t understand.

When Avery got to DSU, his GPA was a 2.88 GPA. That fall, he failed two classes and got a D in another. He did a little better in the spring.

One class in particular challenged him: 2-D design. He’d failed it repeatedly, but it kept getting put on his schedule. Deloris even tried to see if Avery could take a similar course at MDCC or Mississippi Valley State University.

By summer 2021, Avery’s GPA had dropped to 2.39. He received a warning from the financial aid office for not making satisfactory academic progress.In order to get more financial aid, Avery had to file an appeal form. He wrote that the reason he failed some classes was because online learning was “giving me trouble to figure out what the teacher is looking for in an assignment.”

“If things continue to look up in the future and we can get back to attending class in person, I believe I will do a lot better,” he wrote.

The meeting with the dean lasted 45 minutes.

There was a process for Avery to get re-admitted to the art program, Green had told them, and it was easy. If the adviser was available, he could help Avery make a plan that day and the suspension would be lifted.

Avery and Deloris walked out of Green’s office with palpable relief. Deloris had tears in her eyes, and Avery’s posture had relaxed.

But the more Deloris thought about the meeting, it started to bother her. If the process was as easy as Greensaid, why did it take Deloris and Avery so much effort to make it happen?

They’d soon see it wasn’t going to be easy.

The next day, Avery and Deloris drove back to DSU so he could sign up for classes. When they got to his adviser’s office, the re-admittance plan was written and printed out. His adviser had already signed it. All Avery had to do was sign it too.

Other elements of the plan spoke to the lack of input from Avery: His schedule once again included 2-D design.Nobody mentioned course substitutions, a common type of acommodation, as an option.

Deloris was confused. She thought they were going to create the plan together. It reminded Deloris of a dynamic she’d seen before between Avery and authority figures: “They lead the conversation,” she said, “and give you little to say.”

Still, at least Avery was no longer suspended.

Then on Jan. 19, Avery received a puzzling letter from financial aid after he’d emailed them with a question. It read: “Avery, We are showing that you are currently on suspension for the Spring 2023 semester.”

He’d have to go through another appeals process to get his federal financial aid, including the Pell Grant and student loans, reinstated. Otherwise, Deloris would be on the hook for tuition — all $9,000, a sum she can’t afford. Avery would have to drop out.

No one had mentioned there’d be a second process for financial aid, Deloris said. Just like every success, there was another yet another roadblock.

If Avery can stay in school, he’ll graduate next year. But he won’t know for another month if he’ll get financial aid this semester or not.

Deloris and Avery’s brother, Alex, said they think he is holding back from sharing how disappointed he is with his experience at DSU because he doesn’t want to get anyone in trouble.

She thinks about just how much noise it took her and Avery to get help from the dean, and how quickly and easily the university fixed the issues in comparison.

“If I didn’t say anything, then what would happen? He would’ve just been left out,” Deloris said. “What if I was in one of those stages where I’m really sick and I’m in the bed and I can’t go nowhere. Then what? I want to trust that if I can’t come with him, he’s still going to be treated fairly. And given time. And effort.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=205853

Mississippi Today

Trump nominates Baxter Kruger, Scott Leary for Mississippi U.S. attorney posts

President Donald Trump on Tuesday nominated Baxter Kruger to become Mississippi’s new U.S. attorney in the Southern District and Scott Leary to become U.S. attorney for the Northern District.

The two nominations will head to the U.S. Senate for consideration. If confirmed, the two will oversee federal criminal prosecutions and investigations in the state.

Kruger graduated from the Mississippi College School of Law in 2015 and was previously an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District. He is currently the director of the Mississippi Office of Homeland Security.

Sean Tindell, the Mississippi Department of Public Safety commissioner, oversees the state’s Homeland Security Office. He congratulated Kruger on social media and praised his leadership at the agency.

“Thank you for your outstanding leadership at the Mississippi Office of Homeland Security and for your dedicated service to our state,” Tindell wrote. “Your hard work and commitment have not gone unnoticed and this nomination is a testament to that!”

Leary graduated from the University of Mississippi School of Law, and he has been a federal prosecutor for most of his career.

He worked for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Western District of Tennessee in Memphis from 2002 to 2008. Afterward, he worked at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Mississippi in Oxford, where he is currently employed.

Leary told Mississippi Today that he is honored to be nominated for the position, and he looks forward to the Senate confirmation process.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Trump nominates Baxter Kruger, Scott Leary for Mississippi U.S. attorney posts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a straightforward news report on President Donald Trump’s nominations of Baxter Kruger and Scott Leary for U.S. attorney positions in Mississippi. It focuses on factual details about their backgrounds, qualifications, and official responses without employing loaded language or framing that favors a particular ideological perspective. The tone is neutral, with quotes and descriptions that serve to inform rather than persuade. While it reports on a political appointment by a Republican president, the coverage remains balanced and refrains from editorializing, thus adhering to neutral, factual reporting.

Mississippi Today

Jackson’s performing arts venue Thalia Mara Hall is now open

After more than 10 months closed due to mold, asbestos and issues with the air conditioning system, Thalia Mara Hall has officially reopened.

Outgoing Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba announced the reopening of Thalia Mara Hall during his final press conference held Monday on the arts venue’s steps.

“Today marks what we view as a full circle moment, rejoicing in the iconic space where community has come together for decades in the city of Jackson,” Lumumba said. “Thalia Mara has always been more than a venue. It has been a gathering place for people in the city of Jackson. From its first class ballet performances to gospel concerts, Thalia Mara Hall has been the backdrop for our city’s rich cultural history.”

Thalia Mara Hall closed last August after mold was found in parts of the building. The issues compounded from there, with malfunctioning HVAC systems and asbestos remediation. On June 6, the Mississippi State Fire Marshal’s Office announced that Thalia Mara Hall had finally passed inspection.

“We’re not only excited to have overcome many of the challenges that led to it being shuttered for a period of time,” Lumumba said. “We are hopeful for the future of this auditorium, that it may be able to provide a more up-to-date experience for residents, inviting shows that people are able to see across the world, bringing them here to Jackson. So this is an investment in the future.”

In total, Emad Al-Turk, a city contracted engineer and owner of Al-Turk Planning, estimates that $5 million in city and state funds went into bringing Thalia Mara Hall up to code.

The venue still has work to be completed, including reinstalling the fire curtain. The beam in which the fire curtain will be anchored has asbestos in it, so it will have to be remediated. In addition, a second air-conditioning chiller needs to be installed to properly cool the building. Until it’s installed, which could take months, Thalia Mara Hall will be operating at a lower seating capacity of about 800.

“Primarily because of the heat,” Al-Turk said. “The air conditioning would not be sufficient to actually accommodate the 2,000 people at full capacity, but starting in the fall, that should not be a problem.”

Al-Turk said the calendar is open for the city to begin booking events, though none have been scheduled for July.

“We’re very proud,” he said. “This took a little bit longer than what we anticipated, but we had probably seven or eight different contractors we had to coordinate with and all of them did a superb job to get us where we are today.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Jackson’s performing arts venue Thalia Mara Hall is now open appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a straightforward report on the reopening of Thalia Mara Hall in Jackson, focusing on facts and statements from city officials without promoting any ideological viewpoint. The tone is neutral and positive, emphasizing the community and cultural significance of the venue while detailing the challenges overcome during renovations. The coverage centers on public investment and future prospects, without partisan framing or editorializing. While quotes from Mayor Lumumba and a city engineer highlight optimism and civic pride, the article maintains balanced, factual reporting rather than advancing a political agenda.

Mississippi Today

‘Hurdles waiting in the shadows’: Lumumba reflects on challenges and triumphs on final day as Jackson mayor

On his last day as mayor of Jackson, Chokwe Antar Lumumba recounted accomplishments, praised his executive team and said he has no plans to seek office again.

He spoke during a press conference outside of the city’s Thalia Mara Hall, which was recently cleared for reopening after nearly a year of remediation. The briefing, meant to give media members a peek inside the downtown theater, marked one of Lumumba’s final forays as mayor.

Longtime state Sen. John Horhn — who defeated Lumumba in the Democratic primary runoff — will be inaugurated as mayor Tuesday, but Lumumba won’t be present. Not for any contentious reason, the 42-year-old mayor noted, but because he returns to his private law practice Tuesday.

“I’ve got to work now, y’all,” Lumumba said. “I’ve got a job.”

Thalia Mara Hall’s presumptive comeback was a fitting end for Lumumba, who pledged to make Jackson the most radical city in America but instead spent much of his eight years in office parrying one emergency after another. The auditorium was built in 1968 and closed nearly 11 months ago after workers found mold caused by a faulty HVAC system – on top of broken elevators, fire safety concerns and vandalism.

“This job is a fast-pitched sport,” Lumumba said. “There’s an abundance of challenges that have to be addressed, and it seems like the moment that you’ve gotten over one hurdle, there’s another one that is waiting in the shadows.”

Outside the theater Monday, Lumumba reflected on the high points of his leadership instead of the many crises — some seemingly self-inflicted — he faced as mayor.

He presided over the city during the coronavirus pandemic and the rise in crime it brought, but also the one-two punch of the 2021 and 2022 water crises, exacerbated by the city’s mismanagement of its water plants, and the 18-day pause in trash pickup spurred by Lumumba’s contentious negotiations with the city council in 2023.

Then in 2024, Lumumba was indicted alongside other city and county officials in a sweeping federal corruption probe targeting the proposed development of a hotel across from the city’s convention center, a project that has remained stalled in a 20-year saga of failed bids and political consternation.

Slated for trial next year, Lumumba has repeatedly maintained his innocence.

The city’s youngest mayor also brought some victories to Jackson, particularly in his first year in office. In 2017, he ended a furlough of city employees and worked with then-Gov. Phil Bryant to avoid a state takeover of Jackson Public Schools. In 2019, the city successfully sued German engineering firm Siemens and its local contractors for $89 million over botched work installing the city’s water-sewer billing infrastructure.

“I think that that was a pivotal moment to say that this city is going to hold people responsible for the work that they do,” Lumumba said.

Lumumba had more time than any other mayor to usher in the 1% sales tax, which residents approved in 2014 to fund infrastructure improvements.

“We paved 144 streets,” he said. “There are residents that still are waiting on their roads to be repaved. And you don’t really feel it until it’s your street that gets repaved, but that is a significant undertaking.”

And under his administration, crime has fallen dramatically recently, with homicides cut by a third and shootings cut in half in the last year.

Lumumba was first elected in 2017 after defeating Tony Yarber, a business-friendly mayor who faced his own scandals as mayor. A criminal justice attorney, Lumumba said he never planned to seek office until the stunning death of his father, Chokwe Lumumba Sr., eight months into his first term as mayor in 2014.

“I can say without reservation, and unequivocally, we remember where we started. We are in a much better position than we started,” Lumumba said.

Lumumba said he has sat down with Horhn in recent months, answered questions “as extensively as I could,” and promised to remain reachable to the new mayor.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'Hurdles waiting in the shadows': Lumumba reflects on challenges and triumphs on final day as Jackson mayor appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article reports on outgoing Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba’s reflections without overt editorializing but subtly frames his tenure within progressive contexts, emphasizing his self-described goal to make Jackson “the most radical city in America.” The piece highlights his accomplishments alongside challenges, including public crises and a federal indictment, maintaining a factual tone yet noting contentious moments like labor disputes and governance issues. While it avoids partisan rhetoric, the focus on social justice efforts, infrastructure investment, and crime reduction, as well as positive framing of Lumumba’s achievements, aligns with a center-left perspective that values progressive governance and accountability.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Defendant in auditor’s ‘second largest’ embezzlement case in history goes free

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

Are you addicted to ‘fridge cigarettes’? Here’s what the Gen Z term means

-

The Conversation6 days ago

Toxic algae blooms are lasting longer than before in Lake Erie − why that’s a worry for people and pets

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed6 days ago

5 teen boys caught on video using two stolen cars during crash-and-grab at Memphis gas station

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed5 days ago

Federal investigation launched into Minnesota after transgender athlete leads team to championship

-

Local News6 days ago

St. Martin trio becomes the first females in Mississippi to sign Flag Football Scholarships

-

Local News6 days ago

Mississippi Power shares resources and tips for lowering energy bill in the summer

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Error that caused Medicaid denials has been corrected, says cabinet in response to auditor letter