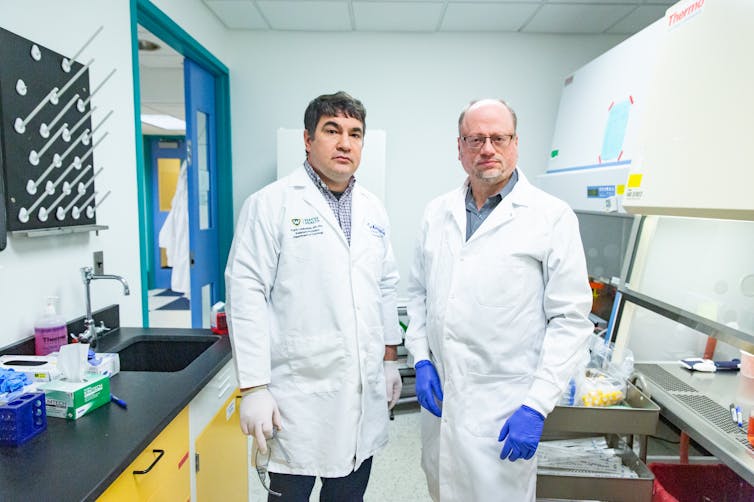

Assistant professor Frank Cackowski, left, and researcher Steven Zielske at Wayne State University in Detroit became suspicious of a paper on cancer research that was eventually retracted. Amy Sacka, CC BY-ND

Frederik Joelving, Retraction Watch; Cyril Labbé, Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), and Guillaume Cabanac, Institut de Recherche en Informatique de Toulouse

Over the past decade, furtive commercial entities around the world have industrialized the production, sale and dissemination of bogus scholarly research, undermining the literature that everyone from doctors to engineers rely on to make decisions about human lives.

It is exceedingly difficult to get a handle on exactly how big the problem is. Around 55,000 scholarly papers have been retracted to date, for a variety of reasons, but scientists and companies who screen the scientific literature for telltale signs of fraud estimate that there are many more fake papers circulating – possibly as many as several hundred thousand. This fake research can confound legitimate researchers who must wade through dense equations, evidence, images and methodologies only to find that they were made up.

Even when the bogus papers are spotted – usually by amateur sleuths on their own time – academic journals are often slow to retract the papers, allowing the articles to taint what many consider sacrosanct: the vast global library of scholarly work that introduces new ideas, reviews other research and discusses findings.

These fake papers are slowing down research that has helped millions of people with lifesaving medicine and therapies from cancer to COVID-19. Analysts’ data shows that fields related to cancer and medicine are particularly hard hit, while areas like philosophy and art are less affected. Some scientists have abandoned their life’s work because they cannot keep pace given the number of fake papers they must bat down.

The problem reflects a worldwide commodification of science. Universities, and their research funders, have long used regular publication in academic journals as requirements for promotions and job security, spawning the mantra “publish or perish.”

But now, fraudsters have infiltrated the academic publishing industry to prioritize profits over scholarship. Equipped with technological prowess, agility and vast networks of corrupt researchers, they are churning out papers on everything from obscure genes to artificial intelligence in medicine.

These papers are absorbed into the worldwide library of research faster than they can be weeded out. About 119,000 scholarly journal articles and conference papers are published globally every week, or more than 6 million a year. Publishers estimate that, at most journals, about 2% of the papers submitted – but not necessarily published – are likely fake, although this number can be much higher at some publications.

While no country is immune to this practice, it is particularly pronounced in emerging economies where resources to do bona fide science are limited – and where governments, eager to compete on a global scale, push particularly strong “publish or perish” incentives.

As a result, there is a bustling online underground economy for all things scholarly publishing. Authorship, citations, even academic journal editors, are up for sale. This fraud is so prevalent that it has its own name: paper mills, a phrase that harks back to “term-paper mills”, where students cheat by getting someone else to write a class paper for them.

The impact on publishers is profound. In high-profile cases, fake articles can hurt a journal’s bottom line. Important scientific indexes – databases of academic publications that many researchers rely on to do their work – may delist journals that publish too many compromised papers. There is growing criticism that legitimate publishers could do more to track and blacklist journals and authors who regularly publish fake papers that are sometimes little more than artificial intelligence-generated phrases strung together.

To better understand the scope, ramifications and potential solutions of this metastasizing assault on science, we – a contributing editor at Retraction Watch, a website that reports on retractions of scientific papers and related topics, and two computer scientists at France’s Université Toulouse III–Paul Sabatier and Université Grenoble Alpes who specialize in detecting bogus publications – spent six months investigating paper mills.

This included, by some of us at different times, trawling websites and social media posts, interviewing publishers, editors, research-integrity experts, scientists, doctors, sociologists and scientific sleuths engaged in the Sisyphean task of cleaning up the literature. It also involved, by some of us, screening scientific articles looking for signs of fakery.

Problematic Paper Screener: Trawling for fraud in the scientific literature

What emerged is a deep-rooted crisis that has many researchers and policymakers calling for a new way for universities and many governments to evaluate and reward academics and health professionals across the globe.

Just as highly biased websites dressed up to look like objective reporting are gnawing away at evidence-based journalism and threatening elections, fake science is grinding down the knowledge base on which modern society rests.

As part of our work detecting these bogus publications, co-author Guillaume Cabanac developed the Problematic Paper Screener, which filters 130 million new and old scholarly papers every week looking for nine types of clues that a paper might be fake or contain errors. A key clue is a tortured phrase – an awkward wording generated by software that replaces common scientific terms with synonyms to avoid direct plagiarism from a legitimate paper.

Problematic Paper Screener: Trawling for fraud in the scientific literature

An obscure molecule

Frank Cackowski at Detroit’s Wayne State University was confused.

The oncologist was studying a sequence of chemical reactions in cells to see if they could be a target for drugs against prostate cancer. A paper from 2018 from 2018 in the American Journal of Cancer Research piqued his interest when he read that a little-known molecule called SNHG1 might interact with the chemical reactions he was exploring. He and fellow Wayne State researcher Steven Zielske began a series of experiments to learn more about the link. Surprisingly, they found there wasn’t a link.

Meanwhile, Zielske had grown suspicious of the paper. Two graphs showing results for different cell lines were identical, he noticed, which “would be like pouring water into two glasses with your eyes closed and the levels coming out exactly the same.” Another graph and a table in the article also inexplicably contained identical data.

Zielske described his misgivings in an anonymous post in 2020 at PubPeer, an online forum where many scientists report potential research misconduct, and also contacted the journal’s editor. Shortly thereafter, the journal pulled the paper, citing “falsified materials and/or data.”

“Science is hard enough as it is if people are actually being genuine and trying to do real work,” says Cackowski, who also works at the Karmanos Cancer Institute in Michigan. “And it’s just really frustrating to waste your time based on somebody’s fraudulent publications.”

Wayne State scientists Frank Cackowski and Steven Zielske carried out experiments based on a paper they later found to contain false data. Amy Sacka, CC BY-ND

He worries that the bogus publications are slowing down “legitimate research that down the road is going to impact patient care and drug development.”

The two researchers eventually found that SNHG1 did appear to play a part in prostate cancer, though not in the way the suspect paper suggested. But it was a tough topic to study. Zielske combed through all the studies on SNHG1 and cancer – some 150 papers, nearly all from Chinese hospitals – and concluded that “a majority” of them looked fake. Some reported using experimental reagents known as primers that were “just gibberish,” for instance, or targeted a different gene than what the study said, according to Zielske. He contacted several of the journals, he said, but received little response. “I just stopped following up.”

The many questionable articles also made it harder to get funding, Zielske said. The first time he submitted a grant application to study SNHG1, it was rejected, with one reviewer saying “the field was crowded,” Zielske recalled. The following year, he explained in his application how most of the literature likely came from paper mills. He got the grant.

Today, Zielske said, he approaches new research differently than he used to: “You can’t just read an abstract and have any faith in it. I kind of assume everything’s wrong.”

Legitimate academic journals evaluate papers before they are published by having other researchers in the field carefully read them over. This peer review process is designed to stop flawed research from being disseminated, but is far from perfect.

Reviewers volunteer their time, typically assume research is real and so don’t look for signs of fraud. And some publishers may try to pick reviewers they deem more likely to accept papers, because rejecting a manuscript can mean losing out on thousands of dollars in publication fees.

“Even good, honest reviewers have become apathetic” because of “the volume of poor research coming through the system,” said Adam Day, who directs Clear Skies, a company in London that develops data-based methods to help spot falsified papers and academic journals. “Any editor can recount seeing reports where it’s obvious the reviewer hasn’t read the paper.”

With AI, they don’t have to: New research shows that many reviews are now written by ChatGPT and similar tools.

To expedite the publication of one another’s work, some corrupt scientists form peer review rings. Paper mills may even create fake peer reviewers impersonating real scientists to ensure their manuscripts make it through to publication. Others bribe editors or plant agents on journal editorial boards.

María de los Ángeles Oviedo-García, a professor of marketing at the University of Seville in Spain, spends her spare time hunting for suspect peer reviews from all areas of science, hundreds of which she has flagged on PubPeer. Some of these reviews are the length of a tweet, others ask authors to cite the reviewer’s work even if it has nothing to do with the science at hand, and many closely resemble other peer reviews for very different studies – evidence, in her eyes, of what she calls “review mills.”

PubPeer comment from María de los Ángeles Oviedo-García pointing out that a peer review report is very similar to two other reports. She also points out that authors and citations for all three are either anonymous or the same person – both hallmarks of fake papers.

“One of the demanding fights for me is to keep faith in science,” says Oviedo-García, who tells her students to look up papers on PubPeer before relying on them too heavily. Her research has been slowed down, she adds, because she now feels compelled to look for peer review reports for studies she uses in her work. Often there aren’t any, because “very few journals publish those review reports,” Oviedo-García says.

An ‘absolutely huge’ problem

It is unclear when paper mills began to operate at scale. The earliest article retracted due to suspected involvement of such agencies was published in 2004, according to the Retraction Watch Database, which contains details about tens of thousands of retractions. (The database is operated by The Center for Scientific Integrity, the parent nonprofit of Retraction Watch.) Nor is it clear exactly how many low-quality, plagiarized or made-up articles paper mills have spawned.

But the number is likely to be significant and growing, experts say. One Russia-linked paper mill in Latvia, for instance, claims on its website to have published “more than 12,650 articles” since 2012.

An analysis of 53,000 papers submitted to six publishers – but not necessarily published – found the proportion of suspect papers ranged from 2% to 46% across journals. And the American publisher Wiley, which has retracted more than 11,300 compromised articles and closed 19 heavily affected journals in its erstwhile Hindawi division, recently said its new paper-mill detection tool flags up to 1 in 7 submissions.

Day, of Clear Skies, estimates that as many as 2% of the several million scientific works published in 2022 were milled. Some fields are more problematic than others. The number is closer to 3% in biology and medicine, and in some subfields, like cancer, it may be much larger, according to Day. Despite increased awareness today, “I do not see any significant change in the trend,” he said. With improved methods of detection, “any estimate I put out now will be higher.”

The paper-mill problem is “absolutely huge,” said Sabina Alam, director of Publishing Ethics and Integrity at Taylor & Francis, a major academic publisher. In 2019, none of the 175 ethics cases that editors escalated to her team was about paper mills, Alam said. Ethics cases include submissions and already published papers. In 2023, “we had almost 4,000 cases,” she said. “And half of those were paper mills.”

Jennifer Byrne, an Australian scientist who now heads up a research group to improve the reliability of medical research, submitted testimony for a hearing of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Science, Space, and Technology in July 2022. She noted that 700, or nearly 6%, of 12,000 cancer research papers screened had errors that could signal paper mill involvement. Byrne shuttered her cancer research lab in 2017 because the genes she had spent two decades researching and writing about became the target of an enormous number of fake papers. A rogue scientist fudging data is one thing, she said, but a paper mill could churn out dozens of fake studies in the time it took her team to publish a single legitimate one.

“The threat of paper mills to scientific publishing and integrity has no parallel over my 30-year scientific career …. In the field of human gene science alone, the number of potentially fraudulent articles could exceed 100,000 original papers,” she wrote to lawmakers, adding, “This estimate may seem shocking but is likely to be conservative.”

In one area of genetics research – the study of noncoding RNA in different types of cancer – “We’re talking about more than 50% of papers published are from mills,” Byrne said. “It’s like swimming in garbage.”

In 2022, Byrne and colleagues, including two of us, found that suspect genetics research, despite not having an immediate impact on patient care, still informs the work of other scientists, including those running clinical trials. Publishers, however, are often slow to retract tainted papers, even when alerted to obvious signs of fraud. We found that 97% of the 712 problematic genetics research articles we identified remained uncorrected within the literature.

When retractions do happen, it is often thanks to the efforts of a small international community of amateur sleuths like Oviedo-García and those who post on PubPeer.

Jillian Goldfarb, an associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Cornell University and a former editor of the Elsevier journal Fuel, laments the publisher’s handling of the threat from paper mills.

“I was assessing upwards of 50 papers every day,” she said in an email interview. While she had technology to detect plagiarism, duplicate submissions and suspicious author changes, it was not enough. “It’s unreasonable to think that an editor – for whom this is not usually their full-time job – can catch these things reading 50 papers at a time. The time crunch, plus pressure from publishers to increase submission rates and citations and decrease review time, puts editors in an impossible situation.”

In October 2023, Goldfarb resigned from her position as editor of Fuel. In a LinkedIn post about her decision, she cited the company’s failure to move on dozens of potential paper-mill articles she had flagged; its hiring of a principal editor who reportedly “engaged in paper and citation milling”; and its proposal of candidates for editorial positions “with longer PubPeer profiles and more retractions than most people have articles on their CVs, and whose names appear as authors on papers-for-sale websites.”

“This tells me, our community, and the public, that they value article quantity and profit over science,” Goldfarb wrote.

In response to questions about Goldfarb’s resignation, an Elsevier spokesperson told The Conversation that it “takes all claims about research misconduct in our journals very seriously” and is investigating Goldfarb’s claims. The spokesperson added that Fuel’s editorial team has “been working to make other changes to the journal to benefit authors and readers.”

That’s not how it works, buddy

Business proposals had been piling up for years in the inbox of João de Deus Barreto Segundo, managing editor of six journals published by the Bahia School of Medicine and Public Health in Salvador, Brazil. Several came from suspect publishers on the prowl for new journals to add to their portfolios. Others came from academics suggesting fishy deals or offering bribes to publish their paper.

In one email from February 2024, an assistant professor of economics in Poland explained that he ran a company that worked with European universities. “Would you be interested in collaboration on the publication of scientific articles by scientists who collaborate with me?” Artur Borcuch inquired. “We will then discuss possible details and financial conditions.”

A university administrator in Iraq was more candid: “As an incentive, I am prepared to offer a grant of $500 for each accepted paper submitted to your esteemed journal,” wrote Ahmed Alkhayyat, head of the Islamic University Centre for Scientific Research, in Najaf, and manager of the school’s “world ranking.”

“That’s not how it works, buddy,” Barreto Segundo shot back.

In email to The Conversation, Borcuch denied any improper intent. “My role is to mediate in the technical and procedural aspects of publishing an article,” Borcuch said, adding that, when working with multiple scientists, he would “request a discount from the editorial office on their behalf.” Informed that the Brazilian publisher had no publication fees, Borcuch said a “mistake” had occurred because an “employee” sent the email for him “to different journals.”

Academic journals have different payment models. Many are subscription-based and don’t charge authors for publishing, but have hefty fees for reading articles. Libraries and universities also pay large sums for access.

A fast-growing open-access model – where anyone can read the paper – includes expensive publication fees levied on authors to make up for the loss of revenue in selling the articles. These payments are not meant to influence whether or not a manuscript is accepted.

The Bahia School of Medicine and Public Health, among others, doesn’t charge authors or readers, but Barreto Segundo’s employer is a small player in the scholarly publishing business, which brings in close to $30 billion a year on profit margins as high as 40%. Academic publishers make money largely from subscription fees from institutions like libraries and universities, individual payments to access paywalled articles, and open-access fees paid by authors to ensure their articles are free for anyone to read.

The industry is lucrative enough that it has attracted unscrupulous actors eager to find a way to siphon off some of that revenue.

Ahmed Torad, a lecturer at Kafr El Sheikh University in Egypt and editor-in-chief of the Egyptian Journal of Physiotherapy, asked for a 30% kickback for every article he passed along to the Brazilian publisher. “This commission will be calculated based on the publication fees generated by the manuscripts I submit,” Torad wrote, noting that he specialized “in connecting researchers and authors with suitable journals for publication.”

Apparently, he failed to notice that Bahia School of Medicine and Public Health doesn’t charge author fees.

Like Borcuch, Alkhayyat denied any improper intent. He said there had been a “misunderstanding” on the editor’s part, explaining that the payment he offered was meant to cover presumed article-processing charges. “Some journals ask for money. So this is normal,” Alkhayyat said.

Torad explained that he had sent his offer to source papers in exchange for a commission to some 280 journals, but had not forced anyone to accept the manuscripts. Some had balked at his proposition, he said, despite regularly charging authors thousands of dollars to publish. He suggested that the scientific community wasn’t comfortable admitting that scholarly publishing has become a business like any other, even if it’s “obvious to many scientists.”

The unwelcome advances all targeted one of the journals Barreto Segundo managed, The Journal of Physiotherapy Research, soon after it was indexed in Scopus, a database of abstracts and citations owned by the publisher Elsevier.

Along with Clarivate’s Web of Science, Scopus has become an important quality stamp for scholarly publications globally. Articles in indexed journals are money in the bank for their authors: They help secure jobs, promotions, funding and, in some countries, even trigger cash rewards. For academics or physicians in poorer countries, they can be a ticket to the global north.

Consider Egypt, a country plagued by dubious clinical trials. Universities there commonly pay employees large sums for international publications, with the amount depending on the journal’s impact factor. A similar incentive structure is hardwired into national regulations: To earn the rank of full professor, for example, candidates must have at least five publications in two years, according to Egypt’s Supreme Council of Universities. Studies in journals indexed in Scopus or Web of Science not only receive extra points, but they also are exempt from further scrutiny when applicants are evaluated. The higher a publication’s impact factor, the more points the studies get.

With such a focus on metrics, it has become common for Egyptian researchers to cut corners, according to a physician in Cairo who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. Authorship is frequently gifted to colleagues who then return the favor later, or studies may be created out of whole cloth. Sometimes an existing legitimate paper is chosen from the literature, and key details such as the type of disease or surgery are then changed and the numbers slightly modified, the source explained.

It affects clinical guidelines and medical care, “so it’s a shame,” the physician said.

Ivermectin, a drug used to treat parasites in animals and humans, is a case in point. When some studies showed that it was effective against COVID-19, ivermectin was hailed as a “miracle drug” early in the pandemic. Prescriptions surged, and along with them calls to U.S. poison centers; one man spent nine days in the hospital after downing an injectable formulation of the drug that was meant for cattle, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As it turned out, nearly all of the research that showed a positive effect on COVID-19 had indications of fakery, the BBC and others reported – including a now-withdrawn Egyptian study. With no apparent benefit, patients were left with just side effects.

Research misconduct isn’t limited to emerging economies, having recently felled university presidents and top scientists at government agencies in the United States. Neither is the emphasis on publications. In Norway, for example, the government allocates funding to research institutes, hospitals and universities based on how many scholarly works employees publish, and in which journals. The country has decided to partly halt this practice starting in 2025.

“There’s a huge academic incentive and profit motive,” says Lisa Bero, a professor of medicine and public health at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus and the senior research-integrity editor at the Cochrane Collaboration, an international nonprofit organization that produces evidence reviews about medical treatments. “I see it at every institution I’ve worked at.”

But in the global south, the publish-or-perish edict runs up against underdeveloped research infrastructures and education systems, leaving scientists in a bind. For a Ph.D., the Cairo physician who requested anonymity conducted an entire clinical trial single-handedly – from purchasing study medication to randomizing patients, collecting and analyzing data and paying article-processing fees. In wealthier nations, entire teams work on such studies, with the tab easily running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“Research is quite challenging here,” the physician said. That’s why scientists “try to manipulate and find easier ways so they get the job done.”

Institutions, too, have gamed the system with an eye to international rankings. In 2011, the journal Science described how prolific researchers in the United States and Europe were offered hefty payments for listing Saudi universities as secondary affiliations on papers. And in 2023, the magazine, in collaboration with Retraction Watch, uncovered a massive self-citation ploy by a top-ranked dental school in India that forced undergraduate students to publish papers referencing faculty work.

The root – and solutions

Such unsavory schemes can be traced back to the introduction of performance-based metrics in academia, a development driven by the New Public Management movement that swept across the Western world in the 1980s, according to Canadian sociologist of science Yves Gingras of the Université du Québec à Montréal. When universities and public institutions adopted corporate management, scientific papers became “accounting units” used to evaluate and reward scientific productivity rather than “knowledge units” advancing our insight into the world around us, Gingras wrote.

This transformation led many researchers to compete on numbers instead of content, which made publication metrics poor measures of academic prowess. As Gingras has shown, the controversial French microbiologist Didier Raoult, who now has more than a dozen retractions to his name, has an h-index – a measure combining publication and citation numbers – that is twice as high as that of Albert Einstein – “proof that the index is absurd,” Gingras said.

Worse, a sort of scientific inflation, or “scientometric bubble,” has ensued, with each new publication representing an increasingly small increment in knowledge. “We publish more and more superficial papers, we publish papers that have to be corrected, and we push people to do fraud,” said Gingras.

In terms of career prospects of individual academics, too, the average value of a publication has plummeted, triggering a rise in the number of hyperprolific authors. One of the most notorious cases is Spanish chemist Rafael Luque, who in 2023 reportedly published a study every 37 hours.

In 2024, Landon Halloran, a geoscientist at the University of Neuchâtel, in Switzerland, received an unusual job application for an opening in his lab. A researcher with a Ph.D. from China had sent him his CV. At 31, the applicant had amassed 160 publications in Scopus-indexed journals, 62 of them in 2022 alone, the same year he obtained his doctorate. Although the applicant was not the only one “with a suspiciously high output,” according to Halloran, he stuck out. “My colleagues and I have never come across anything quite like it in the geosciences,” he said.

According to industry insiders and publishers, there is more awareness now of threats from paper mills and other bad actors. Some journals routinely check for image fraud. A bad AI-generated image showing up in a paper can either be a sign of a scientist taking an ill-advised shortcut, or a paper mill.

The Cochrane Collaboration has a policy excluding suspect studies from its analyses of medical evidence. The organization also has been developing a tool to help its reviewers spot problematic medical trials, just as publishers have begun to screen submissions and share data and technologies among themselves to combat fraud.

This image, generated by AI, is a visual gobbledygook of concepts around transporting and delivering drugs in the body. For instance, the upper left figure is a nonsensical mix of a syringe, an inhaler and pills. And the pH-sensitive carrier molecule on the lower left is huge, rivaling the size of the lungs. After scientist sleuths pointed out that the published image made no sense, the journal issued a correction.

This graphic is the corrected image that replaced the AI image above. In this case, according to the correction, the journal determined that the paper was legitimate but the scientists had used AI to generate the image describing it.

“People are realizing like, wow, this is happening in my field, it’s happening in your field,” said the Cochrane Collaboration’s Bero”. “So we really need to get coordinated and, you know, develop a method and a plan overall for stamping these things out.”

What jolted Taylor & Francis into paying attention, according to Alam, the director of Publishing Ethics and Integrity, was a 2020 investigation of a Chinese paper mill by sleuth Elisabeth Bik and three of her peers who go by the pseudonyms Smut Clyde, Morty and Tiger BB8. With 76 compromised papers, the U.K.-based company’s Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology was the most affected journal identified in the probe.

“It opened up a minefield,” says Alam, who also co-chairs United2Act, a project launched in 2023 that brings together publishers, researchers and sleuths in the fight against paper mills. “It was the first time we realized that stock images essentially were being used to represent experiments.”

Taylor & Francis decided to audit the hundreds of articles in its portfolio that contained similar types of images. It doubled Alam’s team, which now has 14.5 positions dedicated to doing investigations, and also began monitoring submission rates. Paper mills, it seemed, weren’t picky customers.

“What they’re trying to do is find a gate, and if they get in, then they just start kind of slamming in the submissions,” Alam said. Seventy-six fake papers suddenly seemed like a drop in the ocean. At one Taylor & Francis journal, for instance, Alam’s team identified nearly 1,000 manuscripts that bore all the marks of coming from a mill, she said.

And in 2023, it rejected about 300 dodgy proposals for special issues. “We’ve blocked a hell of a lot from coming through,” Alam said.

Fraud checkers

A small industry of technology startups has sprung up to help publishers, researchers and institutions spot potential fraud. The website Argos, launched in September 2024 by Scitility, an alert service based in Sparks, Nevada, allows authors to check if new collaborators are trailed by retractions or misconduct concerns. It has flagged tens of thousands of “high-risk” papers, according to the journal Nature.

Fraud-checker tools sift through papers to point to those that should be manually checked and possibly rejected.

Morressier, a scientific conference and communications company based in Berlin, “aims to restore trust in science by improving the way scientific research is published”, according to its website. It offers integrity tools that target the entire research life cycle. Other new paper-checking tools include Signals, by London-based Research Signals, and Clear Skies’ Papermill Alarm.

The fraudsters have not been idle, either. In 2022, when Clear Skies released the Papermill Alarm, the first academic to inquire about the new tool was a paper miller, according to Day. The person wanted access so he could check his papers before firing them off to publishers, Day said. “Paper mills have proven to be adaptive and also quite quick off the mark.”

Given the ongoing arms race, Alam acknowledges that the fight against paper mills won’t be won as long as the booming demand for their products remains.

According to a Nature analysis, the retraction rate tripled from 2012 to 2022 to close to .02%, or around 1 in 5,000 papers. It then nearly doubled in 2023, in large part because of Wiley’s Hindawi debacle. Today’s commercial publishing is part of the problem, Byrne said. For one, cleaning up the literature is a vast and expensive undertaking with no direct financial upside. “Journals and publishers will never, at the moment, be able to correct the literature at the scale and in the timeliness that’s required to solve the paper-mill problem,” Byrne said. “Either we have to monetize corrections such that publishers are paid for their work, or forget the publishers and do it ourselves.”

But that still wouldn’t fix the fundamental bias built into for-profit publishing: Journals don’t get paid for rejecting papers. “We pay them for accepting papers,” said Bodo Stern, a former editor of the journal Cell and chief of Strategic Initiatives at Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a nonprofit research organization and major funder in Chevy Chase, Maryland. “I mean, what do you think journals are going to do? They’re going to accept papers.”

With more than 50,000 journals on the market, even if some are trying hard to get it right, bad papers that are shopped around long enough eventually find a home, Stern added. “That system cannot function as a quality-control mechanism,” he said. “We have so many journals that everything can get published.”

In Stern’s view, the way to go is to stop paying journals for accepting papers and begin looking at them as public utilities that serve a greater good. “We should pay for transparent and rigorous quality-control mechanisms,” he said.

Peer review, meanwhile, “should be recognized as a true scholarly product, just like the original article, because the authors of the article and the peer reviewers are using the same skills,” Stern said. By the same token, journals should make all peer-review reports publicly available, even for manuscripts they turn down. “When they do quality control, they can’t just reject the paper and then let it be published somewhere else,” Stern said. “That’s not a good service.”

Better measures

Stern isn’t the first scientist to bemoan the excessive focus on bibliometrics. “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons,” wrote the late statistician Douglas G. Altman in a much-cited editorial from 1994. “Abandoning using the number of publications as a measure of ability would be a start.”

Nearly two decades later, a group of some 150 scientists and 75 science organizations released the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, or DORA, discouraging the use of the journal impact factor and other measures as proxies for quality. The 2013 declaration has since been signed by more than 25,000 individuals and organizations in 165 countries.

Despite the declaration, metrics remain in wide use today, and scientists say there is a new sense of urgency.

“We’re getting to the point where people really do feel they have to do something” because of the vast number of fake papers, said Richard Sever, assistant director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, in New York, and co-founder of the preprint servers bioRxiv and medRxiv.

Stern and his colleagues have tried to make improvements at their institution. Researchers who wish to renew their seven-year contract have long been required to write a short paragraph describing the importance of their major results. Since the end of 2023, they also have been asked to remove journal names from their applications.

That way, “you can never do what all reviewers do – I’ve done it – look at the bibliography and in just one second decide, ‘Oh, this person has been productive because they have published many papers and they’re published in the right journals,’” says Stern. “What matters is, did it really make a difference?”

Shifting the focus away from convenient performance metrics seems possible not just for wealthy private institutions like Howard Hughes Medical Institute, but also for large government funders. In Australia, for example, the National Health and Medical Research Council in 2022 launched the “top 10 in 10” policy, aiming, in part, to “value research quality rather than quantity of publications.”

Rather than providing their entire bibliography, the agency, which assesses thousands of grant applications every year, asked researchers to list no more than 10 publications from the past decade and explain the contribution each had made to science. According to an evaluation report from April, 2024 close to three-quarters of grant reviewers said the new policy allowed them to concentrate more on research quality than quantity. And more than half said it reduced the time they spent on each application.

Gingras, the Canadian sociologist, advocates giving scientists the time they need to produce work that matters, rather than a gushing stream of publications. He is a signatory to the Slow Science Manifesto: “Once you get slow science, I can predict that the number of corrigenda, the number of retractions, will go down,” he says.

At one point, Gingras was involved in evaluating a research organization whose mission was to improve workplace security. An employee presented his work. “He had a sentence I will never forget,” Gingras recalls. The employee began by saying, “‘You know, I’m proud of one thing: My h-index is zero.’ And it was brilliant.” The scientist had developed a technology that prevented fatal falls among construction workers. “He said, ‘That’s useful, and that’s my job.’ I said, ‘Bravo!’”

Learn more about how the Problematic Paper Screener uncovers compromised papers.

Frederik Joelving, Contributing editor, Retraction Watch; Cyril Labbé, Professor of Computer Science, Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), and Guillaume Cabanac, Professor of Computer Science, Institut de Recherche en Informatique de Toulouse

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.