Kaiser Health News

Epidemic: Zero Pox!

by

Tue, 15 Aug 2023 09:00:00 +0000

In 1973, Bhakti Dastane arrived in Bihar, India, to join the smallpox eradication campaign. She was a year out of medical school and had never cared for anyone with the virus. She believed she was offering something miraculous, saving people from a deadly disease. But some locals did not see it that way.

Episode 3 of “Eradicating Smallpox” explores what happened when public health workers — driven by the motto “zero pox!” — encountered hesitation. These anti-smallpox warriors wanted to achieve 100% vaccination, and they wanted to get there fast. Fueled by that urgency, their tactics were sometimes aggressive — and sometimes, crossed the line.

“I learned about being overzealous and not treating people with respect,” said Steve Jones, another eradication worker based in Bihar in the early ’70s.

To close out the episode, host Céline Gounder speaks with NAACP health researcher Sandhya Kajeepeta about the reverberations of using coercion to achieve public health goals. Kajeepeta’s work documents inequities in the enforcement of covid-19 mandates in New York City.

The Host:

Céline Gounder

Senior Fellow & Editor-at-Large for Public Health, KFF Health News

Céline is senior fellow and editor-at-large for public health with KFF Health News. She is an infectious diseases physician and epidemiologist. She was an assistant commissioner of health in New York City. Between 1998 and 2012, she studied tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa, Lesotho, Malawi, Ethiopia, and Brazil. Gounder also served on the Biden-Harris Transition COVID-19 Advisory Board.

In Conversation with Céline Gounder:

Sandhya Kajeepeta

Epidemiologist and senior researcher with the NAACP’s Thurgood Marshall Institute

Voices from the Episode:

Bhakti Dastane

Gynecologist and former World Health Organization smallpox eradication program worker in Bihar, India

Steve Jones

Physican-epidemiologist and former smallpox eradication campaign worker in India, Bangladesh, and Somalia

Sanjoy Bhattacharya

Medical historian and professor of medical and global health histories at the University of Leeds

Click to open the transcript

Transcript: Zero Pox!

Podcast Transcript Epidemic: “Eradicating Smallpox” Season 2, Episode 3: Zero Pox! Air date: Aug. 15, 2023

Editor’s note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of “Epidemic,” which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. This transcript, generated using transcription software, has been edited for style and clarity. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

TRANSCRIPT

Céline Gounder: When the World Health Organization set out to eradicate smallpox, enthusiastic young doctors and public health workers from all over the world showed up and spread out across the Indian subcontinent.

We had the chance to speak with some of them …

[Music begins]

Yogesh Parashar: People never believed that the world would be free of smallpox, especially India.

Larry Brilliant: There’s no reason to believe you could cure it.

Alan Schnur: This is a terrible disease.

Bill Foege: I was struck immediately by the smell. It was similar to a dead body.

Yogesh Parashar: Any outbreak was an emergency.

Bhakti Dastane: That itself was motivation for us.

Chandrakant Pandav: I said, this is the time to serve my India.

Larry Brilliant: We all seemed so confident that we could do it.

Alan Schnur: That kept all of us in smallpox eradication working long hours under rigorous conditions.

Chandrakant Pandav: It had to be done.

Hardayal Singh: Our duty was to vaccinate each and every person by hook and by crook.

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder: By hook or by crook, vaccinate everyone. These smallpox eradication workers had a shared sense of duty. And they had a slogan: “zero pox!”

Bhakti Dastane: We have to achieve zero pox, so it was our motto: zero pox.

Céline Gounder: That refrain … it became a way for workers to greet one another, even replacing the usual hellos. It was a constant reminder of their shared goal.

Rajendra Deodhar: Whenever one Jeep crosses the other, we used to greet one another as “zero pox.”

Céline Gounder: You’ve just heard the voices of Alan Schnur and Drs. Yogesh Parashar, Larry Brilliant, Bhakti Dastane, Bill Foege, Chandrakant Pandav, Hardayal Singh, and Rajendra Deodhar. We’ll be hearing more from each of them throughout this podcast season.

So, this group of former eradication workers are grayer now. They’re mostly in their 70s. But you can still hear the youthful enthusiasm in their voices. You can feel that sense of purpose.

This episode is about what happened when this zealous bunch encountered hesitation.

Well, actually more than hesitation … real, everyday people, right in front of them, who were skeptical of the vaccine.

And just how far would the eradication workers go to stop smallpox?

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder, and this is “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme music]

Céline Gounder: By the early ’70s, smallpox was coming under control in most of the world. But in India, the disease remained stubbornly entrenched in several areas, including the state of Bihar — in the East.

In some pockets of the region, a lot of people were skeptical about getting the vaccination.

The eradication program sent in a stream of dedicated smallpox workers — on bicycles and in 4×4 trucks — to prowl the countryside and cities.

Bhakti Dastane was among them.

Bhakti Dastane: I’m Dr. Dastane, so I’m a gynecologist and I went to this, uh, WHO [World Health Organization] program, smallpox eradication program, when I was an intern.

Céline Gounder: Bhakti answered the call in 1973. She was a year out of medical school, maybe 27 or 28 years old, and had never cared for anyone with smallpox. She had never even seen an actual smallpox case before.

But she was inspired to help and, when she arrived in Bihar, the program coordinators were surprised to see her. They had been expecting a man. Bhakti and another female physician showed up instead.

[Music starts]

Bhakti Dastane: We were only two lady doctors on that program, the smallpox eradication program. So we have to show them that ladies also can do as good as the gents.

Céline Gounder: Proving they were “as good as the gents” in almost every situation — that was their first task, the thing they had to do before they could get down to the work of finding patients.

Bhakti and a team of about six to eight volunteers went house to house lugging vaccination kits, searching for people with smallpox and anyone they could vaccinate.

Mostly, the men of the household didn’t even want to talk to a female doctor.

Bhakti Dastane: This thing was very new for them, for any female to go and talk to the male people in the house. They don’t give the importance to the female. So they don’t open up and don’t share the things with you. So, it took some time to develop this, uh, trust in them.

[Music ends]

Céline Gounder: In Bhakti’s mind, she was offering health to the people of Bihar, saving them from a deadly disease.

But locals didn’t really see it that way.

Some believed that if they accepted the vaccine, they would anger the Hindu goddess Shitala Mata, and some people from marginalized minority groups — including Muslims and the Indigenous Adivasi — had good reasons not to trust public health workers handing out unsolicited medical advice.

Bhakti Dastane: My reaction was not to get angry. I knew this resistance is going to come. So, I was prepared to convince patiently. And I said, “OK, not today. I will come tomorrow also.”

Céline Gounder: And, over time, she had some success.

One family patriarch thought vaccination was a curse — and told his family this:

Bhakti Dastane: He said, “Don’t listen to her, even if you think she’s saying the right thing.” So, for that person, I said, “OK, I’ll leave it like this.” And then, next day, just went there, not to talk about the smallpox or anything, just spend a day with them.

After three, four days, then he started listening to me. “OK. Now I think you are a good doctor, so, OK. What is it you want us to do?”

Céline Gounder: What Bhakti wanted was to get his entire family vaccinated. And she did it.

[Music comes up under Bhakti]

Bhakti Dastane: And once you put a trust in one family, then the neighborhood also get convinced and then your work becomes easy.

Céline Gounder: Building trust makes the work go easier. That’s a pillar in public health.

But sometimes it can take months and even years to gain the trust of a community. And sometimes … there’s a tension between what’s expedient and what’s ethical.

Health workers are supposed to be patient, but epidemics are not patient.

Smallpox didn’t wait for trust and respect. It kept spreading. And lives were lost.

The smallpox warriors wanted to get to zero pox. And they wanted to get there fast.

Fueled by that urgency, their tactics were sometimes aggressive — and sometimes, crossed the line.

[Music fades out]

Céline Gounder: Passion and frustration collided for Bhakti when she was working in Patna, the capital of Bihar.

People there would sometimes take off in the other direction as soon as they saw the vaccine volunteers.

So, to keep the locals from fleeing, Bhakti added two uniformed police officers to her team.

Bhakti Dastane: Two people, which were at the end of the road, so they couldn’t run away.

Céline Gounder: She resorted to intimidation, Bhakti says. But not violence.

Bhakti Dastane: Hold down and that, that I didn’t do. But scare them with the police or any other thing: “You have to do this, and you have to take this.” Up to that. But not physical force. I, I never used physical force.

Céline Gounder: But other health workers did.

Steve Jones: My name is T. Stephen Jones, and — I go by Steve Jones — and, I had the good fortune to work on smallpox eradication in three countries.

Céline Gounder: Steve was a true believer.

Steve Jones: The idea that you could get rid of this plague that had caused deaths and disfiguration over centuries was just such an astounding idea that I wanted to be able to say that I had been part of it.

Céline Gounder: When he arrived in Bihar in 1974, there was so much work to do.

[Music starts]

Céline Gounder: Juggling more than a hundred different smallpox outbreaks at once. And for each case, he had to survey and vaccinate the 20 or 25 households surrounding the infected home.

Steve says he did a lot to persuade people. Like, he vaccinated himself repeatedly to show it was safe.

But there were times when the push for “zero pox” got the best of him.

Steve Jones: I vaccinated a woman who was not willing to be vaccinated. I had a bifurcated needle and I held onto her arm, and I vaccinated her. And she resisted.

Then the people of the village responded, and it got angry. And I was hit on the head and knocked to the ground.

Céline Gounder: He ended up needing stitches.

Steve Jones: I regret this, and I realized that I did the wrong thing, even if I hadn’t been bonked on the head.

[Music fades out]

Steve Jones: I was passionate and believed that it was a really important goal to achieve, and I made a mistake.

I learned about being overzealous and not treating people with respect.

Céline Gounder: Bhakti Dastane says that she also came away with regrets about resorting to intimidation.

Bhakti Dastane: Definitely using the force was not the proper thing to do, looking back now. But at that time, we were enthusiastic and trying to zero pox and so that a hundred percent vaccination.

[Music starts]

Céline Gounder: During the campaign in India, there were instances of not just coerced vaccination, but of physical force.

Medical historian Sanjoy Bhattacharya is a professor of medical and global health histories at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom.

He says the Adivasi Indigenous people of India were among the most frequently vaccinated under duress.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: They were encircled, by often Indian paramilitaries or police forces, and then groups of Indian and overseas workers would go into these villages.

Céline Gounder: A lot like the treatment of Indigenous people in the U.S., the Adivasi have been traditionally marginalized and exploited. Many of them were understandably suspicious of government health and of course vulnerable to coercion.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: Often kick down doors, often pull people from places they were hiding in and forcibly vaccinate them, literally sit on them and vaccinate them.

[Music out]

Céline Gounder: Today, around 50 years later, Sanjoy has spoken with villagers who still remember.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: They remember these pink, unfriendly — that is a terminology they use — pink, unfriendly people who would come in, shout at them, and not really engage them at all. I mean, what sort of leadership is that?

Céline Gounder: Sanjoy rejects the idea that strong-arm tactics were somehow OK because of the urgency of the mission.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: Efficiency? By whose standard? None of us would like to be sat on by a 6-foot-tall and rather heavy man.

Céline Gounder: And, he says, in the long run, force is usually counterproductive, creating a ripple of pushback, which ends up being more costly than leaving people unprotected.

[Music starts under Sanjoy]

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: Any public health goal can be achieved without force. It needs engagement. It needs self-awareness; it needs humility. It needs money and time.

Céline Gounder: Engagement takes time, and it’s built on trust.

When we come back, epidemiologist and researcher Sandhya Kajeepeta will join us to talk about just that.

Sandhya Kajeepeta: I remember in early 2020 seeing news stories of very violent arrests of Black New Yorkers for alleged violations of covid mandates that were extremely vague.

Céline Gounder: That’s after the break.

[Music out]

Céline Gounder: By the end of April 2020, there had been over 18,000 covid deaths in New York City. I was working at a large public hospital in Manhattan — Bellevue.

Remember, at that time, there’s still a lot we didn’t know.

Our best advice was to tell everyone to stay home.

In cities like New York, police were tasked with enforcing these new rules around social distancing and masking.

But the results, they weren’t always good.

[Music begins]

Newscaster: The 33-year-old seen getting thrown to the ground and slapped repeatedly in what started as social distancing enforcement along Avenue D and East Ninth Street.

Newscaster: It is the most recent incident involving the NYPD [New York Police Department] social distancing enforcement that has come under fire.

[Music out]

Céline Gounder: Seeing that footage of Black New Yorkers being arrested really upset me.

And I wondered, was this enforcement doing more harm than good?

I wanted to know. So, I talked about it with social epidemiologist Sandhya Kajeepeta.

She studied how police enforced these rules and how it impacted public health during the first months of the pandemic.

Sandhya Kajeepeta: In my neighborhood in Harlem, I would see huge numbers of police officers issuing citations and making arrests in response to these mandates. But if I went downtown, to the southern part of Central Park, or to the West Village, I would see parks department employees handing out free masks.

Céline Gounder: I definitely saw that too. Like, just walking to work at Bellevue Hospital, I’d see groups of people picnicking in Madison Square Park — unmasked.

But I never saw the NYPD breaking up those gatherings. That was in a predominantly white neighborhood in midtown Manhattan.

So, Sandhya, when you looked at summons and arrest data, how were the police enforcing those rules?

Sandhya Kajeepeta: We found ultimately that neighborhoods in New York City with a higher percentage of Black residents also had a higher rate of pandemic policing.

Céline Gounder: From your work we see that the enforcement of covid mitigation measures and mandates was unfair, but what about the public health results? Did these measures help curb infections?

Sandhya Kajeepeta: There’s this really clear irony of trying to promote social distancing by instead increasing forced physical interactions between police and community members. And if people were held in jail because of a covid mandate violation, then they faced an even higher risk of covid infection, because the city’s jail was among the country’s top hot spots for coronavirus infections at this time.

It seems very clear that this approach was antithetical to public health broadly and to curbing the spread of the virus.

Céline Gounder: Yeah, and on top of that, it made people more skeptical about the pandemic safety measures we were recommending.

Sandhya Kajeepeta: Yeah, I think there’s certainly a growing body of evidence documenting how police and criminal legal systems more broadly can erode trust in public institutions.

Thinking about the covid pandemic, when I was seeing news coverage of police officers violently arresting and placing their knee on the neck of a Black man in New York, just for allegedly talking to someone too closely, or seeing footage of police forcing a Black woman to the ground in front of her child for allegedly wearing her mask improperly — that’s going to make me question whether public institutions really have our best interests in mind.

I think anyone can see that and recognize that violence and punishment is not getting us to the goal of safeguarding public health and is quite clearly putting people at risk.

Céline Gounder: There will be more epidemics and pandemics in our lifetimes. What would you like to see done differently when we see the next infectious disease outbreak?

Sandhya Kajeepeta: I think the mandates themselves are such a powerful and important message to send to people, that, you know, we’re all working together, we all have an individual responsibility to control the spread of the virus.

But I think when it was announced that police would be used to enforce these mandates, many people in New York City could very quickly predict what would happen, because we’ve seen this racialized pattern of policing be replicated time and time again.

[“Epidemic” theme music begins]

Trust in public institutions is such an important part of encouraging and motivating behavior change. But police enforcement can often have the opposite effect, of eroding that trust.

Céline Gounder: Next time on “Epidemic” …

Tim Miner: Occasionally you have to park your motorcycle, take your shoes and socks off, and walk across a leech-infested paddy field to get to the next case.

Céline Gounder: “Eradicating Smallpox,” our latest season of “Epidemic,” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

Additional support provided by the Sloan Foundation.

This episode was produced by Jenny Gold, Zach Dyer, Taylor Cook, and me.

Our translator and local reporting partner in India was Swagata Yadavar.

Taunya English is our managing editor.

Oona Tempest is our graphics and photo editor.

The show was engineered by Justin Gerrish.

We had extra support from Viki Merrick.

Music in this episode is from the Blue Dot Sessions and Soundstripe. We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

This episode featured news clips from ABC7 New York and NBC 4 New York.

If you enjoyed the show, please tell a friend. And leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find the show.

Follow KFF Health News on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok.

And find me on Twitter @celinegounder. On our socials there’s more about the ideas we’re exploring on the podcasts.

And subscribe to our newsletters at kffhealthnews.org so you’ll never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”

[”Epidemic” theme fades out]

Credits

Taunya English

Managing Editor

Taunya is senior editor for broadcast innovation with KFF Health News, where she leads enterprise audio projects.

Zach Dyer

Senior Producer

Zach is senior producer for audio with KFF Health News, where he supervises all levels of podcast production.

Taylor Cook

Associate Producer

Taylor is associate audio producer for Season 2 of Epidemic. She researches, writes, and fact-checks scripts for the podcast.

Oona Tempest

Photo Editing, Design, Logo Art

Oona is a digital producer and illustrator with KFF Health News. She researched, sourced, and curated the images for the season.

Additional Newsroom Support

Lydia Zuraw, digital producer Tarena Lofton, audience engagement producer Hannah Norman, visual producer and visual reporter Simone Popperl, broadcast editor Chaseedaw Giles, social media manager Mary Agnes Carey, partnerships editor Damon Darlin, executive editor Terry Byrne, copy chief Chris Lee, senior communications officer

Additional Reporting Support

Swagata Yadavar, translator and local reporting partner in IndiaRedwan Ahmed, translator and local reporting partner in Bangladesh

Epidemic is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

To hear other KFF Health News podcasts, click here. Subscribe to Epidemic on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Title: Epidemic: Zero Pox!

Sourced From: kffhealthnews.org/news/podcast/season-2-episode-3-zero-pox/

Published Date: Tue, 15 Aug 2023 09:00:00 +0000

Kaiser Health News

How To Find the Right Medical Rehab Services

Rehabilitation therapy can be a godsend after hospitalization for a stroke, a fall, an accident, a joint replacement, a severe burn, or a spinal cord injury, among other conditions. Physical, occupational, and speech therapy are offered in a variety of settings, including at hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, and at home. It’s crucial to identify a high-quality, safe option with professionals experienced in treating your condition.

What kinds of rehab therapy might I need?

Physical therapy helps patients improve their strength, stability, and movement and reduce pain, usually through targeted exercises. Some physical therapists specialize in neurological, cardiovascular, or orthopedic issues. There are also geriatric and pediatric specialists. Occupational therapy focuses on specific activities (referred to as “occupations”), often ones that require fine motor skills, like brushing teeth, cutting food with a knife, and getting dressed. Speech and language therapy help people communicate. Some patients may need respiratory therapy if they have trouble breathing or need to be weaned from a ventilator.

Will insurance cover rehab?

Medicare, health insurers, workers’ compensation, and Medicaid plans in some states cover rehab therapy, but plans may refuse to pay for certain settings and may limit the amount of therapy you receive. Some insurers may require preauthorization, and some may terminate coverage if you’re not improving. Private insurers often place annual limits on outpatient therapy. Traditional Medicare is generally the least restrictive, while private Medicare Advantage plans may monitor progress closely and limit where patients can obtain therapy.

Should I seek inpatient rehabilitation?

Patients who still need nursing or a doctor’s care but can tolerate three hours of therapy five days a week may qualify for admission to a specialized rehab hospital or to a unit within a general hospital. Patients usually need at least two of the main types of rehab therapy: physical, occupational, or speech. Stays average around 12 days.

How do I choose?

Look for a place that is skilled in treating people with your diagnosis; many inpatient hospitals list specialties on their websites. People with complex or severe medical conditions may want a rehab hospital connected to an academic medical center at the vanguard of new treatments, even if it’s a plane ride away.

“You’ll see youngish patients with these life-changing, fairly catastrophic injuries,” like spinal cord damage, travel to another state for treatment, said Cheri Blauwet, chief medical officer of Spaulding Rehabilitation in Boston, one of 15 hospitals the federal government has praised for cutting-edge work.

But there are advantages in selecting a hospital close to family and friends who can help after you are discharged. Therapists can help train at-home caregivers.

How do I find rehab hospitals?

The discharge planner or caseworker at the acute care hospital should provide options. You can search for inpatient rehabilitation facilities by location or name through Medicare’s Care Compare website. There you can see how many patients the rehab hospital has treated with your condition — the more the better. You can search by specialty through the American Medical Rehabilitation Providers Association, a trade group that lists its members.

Find out what specialized technologies a hospital has, like driving simulators — a car or truck that enable a patient to practice getting in and out of a vehicle — or a kitchen table with utensils to practice making a meal.

How can I be confident a rehab hospital is reliable?

It’s not easy: Medicare doesn’t analyze staffing levels or post on its website results of safety inspections as it does for nursing homes. You can ask your state public health agency or the hospital to provide inspection reports for the last three years. Such reports can be technical, but you should get the gist. If the report says an “immediate jeopardy” was called, that means inspectors identified safety problems that put patients in danger.

The rate of patients readmitted to a general hospital for a potentially preventable reason is a key safety measure. Overall, for-profit rehabs have higher readmission rates than nonprofits do, but there are some with lower readmission rates and some with higher ones. You may not have a nearby choice: There are fewer than 400 rehab hospitals, and most general hospitals don’t have a rehab unit.

You can find a hospital’s readmission rates under Care Compare’s quality section. Rates lower than the national average are better.

Another measure of quality is how often patients are functional enough to go home after finishing rehab rather than to a nursing home, hospital, or health care institution. That measure is called “discharge to community” and is listed under Care Compare’s quality section. Rates higher than the national average are better.

Look for reviews of the hospital on Yelp and other sites. Ask if the patient will see the same therapist most days or a rotating cast of characters. Ask if the therapists have board certifications earned after intensive training to treat a patient’s particular condition.

Visit if possible, and don’t look only at the rooms in the hospital where therapy exercises take place. Injuries often occur in the 21 hours when a patient is not in therapy, but in his or her room or another part of the building. Infections, falls, bedsores, and medication errors are risks. If possible, observe whether nurses promptly respond to call lights, seem overloaded with too many patients, or are apathetically playing on their phones. Ask current patients and their family members if they are satisfied with the care.

What if I can’t handle three hours of therapy a day?

A nursing home that provides rehab might be appropriate for patients who don’t need the supervision of a doctor but aren’t ready to go home. The facilities generally provide round-the-clock nursing care. The amount of rehab varies based on the patient. There are more than 14,500 skilled nursing facilities in the United States, 12 times as many as hospitals offering rehab, so a nursing home may be the only option near you.

You can look for them through Medicare’s Care Compare website. (Read our previous guide to finding a good, well-staffed home to know how to assess the overall staffing.)

What if patients are too frail even for a nursing home?

They might need a long-term care hospital. Those specialize in patients who are in comas, on ventilators, and have acute medical conditions that require the presence of a physician. Patients stay at least four weeks, and some are there for months. Care Compare helps you search. There are fewer than 350 such hospitals.

I’m strong enough to go home. How do I receive therapy?

Many rehab hospitals offer outpatient therapy. You also can go to a clinic, or a therapist can come to you. You can hire a home health agency or find a therapist who takes your insurance and makes house calls. Your doctor or hospital may give you referrals. On Care Compare, home health agencies list whether they offer physical, occupational, or speech therapy. You can search for board-certified therapists on the American Physical Therapy Association’s website.

While undergoing rehab, patients sometimes move from hospital to nursing facility to home, often at the insistence of their insurers. Alice Bell, a senior specialist at the APTA, said patients should try to limit the number of transitions, for their own safety.

“Every time a patient moves from one setting to another,” she said, “they’re in a higher risk zone.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

The post How To Find the Right Medical Rehab Services appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article from KFF Health News provides a comprehensive, fact-based guide to rehabilitation therapy options and how to navigate insurance, care settings, and provider quality. It avoids ideological framing and presents information in a neutral, practical tone aimed at helping consumers make informed medical decisions. While it touches on Medicare and private insurance policies, it does so without political commentary or value judgments, and no partisan viewpoints or advocacy positions are evident. The focus remains on patient care, safety, and informed choice, supporting a nonpartisan, service-oriented approach to health reporting.

Kaiser Health News

States Brace for Reversal of Obamacare Coverage Gains Under Trump’s Budget Bill

Shorter enrollment periods. More paperwork. Higher premiums. The sweeping tax and spending bill pushed by President Donald Trump includes provisions that would not only reshape people’s experience with the Affordable Care Act but, according to some policy analysts, also sharply undermine the gains in health insurance coverage associated with it.

The moves affect consumers and have particular resonance for the 19 states (plus Washington, D.C.) that run their own ACA exchanges.

Many of those states fear that the additional red tape — especially requirements that would end automatic reenrollment — would have an outsize impact on their policyholders. That’s because a greater percentage of people in those states use those rollovers versus shopping around each year, which is more commonly done by people in states that use the federal healthcare.gov marketplace.

“The federal marketplace always had a message of, ‘Come back in and shop,’ while the state-based markets, on average, have a message of, ‘Hey, here’s what you’re going to have next year, here’s what it will cost; if you like it, you don’t have to do anything,’” said Ellen Montz, who oversaw the federal ACA marketplace under the Biden administration as deputy administrator and director at the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight. She is now a managing director with the Manatt Health consulting group.

Millions — perhaps up to half of enrollees in some states — may lose or drop coverage as a result of that and other changes in the legislation combined with a new rule from the Trump administration and the likely expiration at year’s end of enhanced premium subsidies put in place during the covid-19 pandemic. Without an extension of those subsidies, which have been an important driver of Obamacare enrollment in recent years, premiums are expected to rise 75% on average next year. That’s starting to happen already, based on some early state rate requests for next year, which are hitting double digits.

“We estimate a minimum 30% enrollment loss, and, in the worst-case scenario, a 50% loss,” said Devon Trolley, executive director of Pennie, the ACA marketplace in Pennsylvania, which had 496,661 enrollees this year, a record.

Drops of that magnitude nationally, coupled with the expected loss of Medicaid coverage for millions more people under the legislation Trump calls the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” could undo inroads made in the nation’s uninsured rate, which dropped by about half from the time most of the ACA’s provisions went into effect in 2014, when it hovered around 14% to 15% of the population, to just over 8%, according to the most recent data.

Premiums would rise along with the uninsured rate, because older or sicker policyholders are more likely to try to jump enrollment hurdles, while those who rarely use coverage — and are thus less expensive — would not.

After a dramatic all-night session, House Republicans passed the bill, meeting the president’s July 4 deadline. Trump is expected to sign the measure on Independence Day. It would increase the federal deficit by trillions of dollars and cut spending on a variety of programs, including Medicaid and nutrition assistance, to partly offset the cost of extending tax cuts put in place during the first Trump administration.

The administration and its supporters say the GOP-backed changes to the ACA are needed to combat fraud. Democrats and ACA supporters see this effort as the latest in a long history of Republican efforts to weaken or repeal Obamacare. Among other things, the legislation would end several changes put in place by the Biden administration that were credited with making it easier to sign up, such as lengthening the annual open enrollment period and launching a special program for very low-income people that essentially allows them to sign up year-round.

In addition, automatic reenrollment, used by more than 10 million people for 2025 ACA coverage, would end in the 2028 sign-up season. Instead, consumers would have to update their information, starting in August each year, before the close of open enrollment, which would end Dec. 15, a month earlier than currently.

That’s a key change to combat rising enrollment fraud, said Brian Blase, president of the conservative Paragon Health Institute, because it gets at what he calls the Biden era’s “lax verification requirements.”

He blames automatic reenrollment, coupled with the availability of zero-premium plans for people with lower incomes that qualify them for large subsidies, for a sharp uptick in complaints from insurers, consumers, and brokers about fraudulent enrollments in 2023 and 2024. Those complaints centered on consumers’ being enrolled in an ACA plan, or switched from one to another, without authorization, often by commission-seeking brokers.

In testimony to Congress on June 25, Blase wrote that “this simple step will close a massive loophole and significantly reduce improper enrollment and spending.”

States that run their own marketplaces, however, saw few, if any, such problems, which were confined mainly to the 31 states using the federal healthcare.gov.

The state-run marketplaces credit their additional security measures and tighter control over broker access than healthcare.gov for the relative lack of problems.

“If you look at California and the other states that have expanded their Medicaid programs, you don’t see that kind of fraud problem,” said Jessica Altman, executive director of Covered California, the state’s Obamacare marketplace. “I don’t have a single case of a consumer calling Covered California saying, ‘I was enrolled without consent.’”

Such rollovers are common with other forms of health insurance, such as job-based coverage.

“By requiring everyone to come back in and provide additional information, and the fact that they can’t get a tax credit until they take this step, it is essentially making marketplace coverage the most difficult coverage to enroll in,” said Trolley at Pennie, 65% of whose policyholders were automatically reenrolled this year, according to KFF data. KFF is a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Federal data shows about 22% of federal sign-ups in 2024 were automatic-reenrollments, versus 58% in state-based plans. Besides Pennsylvania, the states that saw such sign-ups for more than 60% of enrollees include California, New York, Georgia, New Jersey, and Virginia, according to KFF.

States do check income and other eligibility information for all enrollees — including those being automatically renewed, those signing up for the first time, and those enrolling outside the normal open enrollment period because they’ve experienced a loss of coverage or other life event or meet the rules for the low-income enrollment period.

“We have access to many data sources on the back end that we ping, to make sure nothing has changed. Most people sail through and are able to stay covered without taking any proactive step,” Altman said.

If flagged for mismatched data, applicants are asked for additional information. Under current law, “we have 90 days for them to have a tax credit while they submit paperwork,” Altman said.

That would change under the tax and spending plan before Congress, ending presumptive eligibility while a person submits the information.

A white paper written for Capital Policy Analytics, a Washington-based consultancy that specializes in economic analysis, concluded there appears to be little upside to the changes.

While “tighter verification can curb improper enrollments,” the additional paperwork, along with the expiration of higher premiums from the enhanced tax subsidies, “would push four to six million eligible people out of Marketplace plans, trading limited fraud savings for a surge in uninsurance,” wrote free market economists Ike Brannon and Anthony LoSasso.

“Insurers would be left with a smaller, sicker risk pool and heightened pricing uncertainty, making further premium increases and selective market exits [by insurers] likely,” they wrote.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

The post States Brace for Reversal of Obamacare Coverage Gains Under Trump’s Budget Bill appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content presents a critique of Republican-led changes to the Affordable Care Act, emphasizing potential negative impacts such as increased premiums, reduced enrollment, and the erosion of coverage gains made under the ACA. It highlights the perspective of policy analysts and state officials who express concern over these measures, while also presenting conservative viewpoints, particularly those focusing on fraud reduction. Overall, the tone and framing lean toward protecting the ACA and its expansions, which traditionally aligns with Center-Left media analysis.

Kaiser Health News

Dual Threats From Trump and GOP Imperil Nursing Homes and Their Foreign-Born Workers

In a top-rated nursing home in Alexandria, Virginia, the Rev. Donald Goodness is cared for by nurses and aides from various parts of Africa. One of them, Jackline Conteh, a naturalized citizen and nurse assistant from Sierra Leone, bathes and helps dress him most days and vigilantly intercepts any meal headed his way that contains gluten, as Goodness has celiac disease.

“We are full of people who come from other countries,” Goodness, 92, said about Goodwin House Alexandria’s staff. Without them, the retired Episcopal priest said, “I would be, and my building would be, desolate.”

The long-term health care industry is facing a double whammy from President Donald Trump’s crackdown on immigrants and the GOP’s proposals to reduce Medicaid spending. The industry is highly dependent on foreign workers: More than 800,000 immigrants and naturalized citizens comprise 28% of direct care employees at home care agencies, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other long-term care companies.

But in January, the Trump administration rescinded former President Joe Biden’s 2021 policy that protected health care facilities from Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids. The administration’s broad immigration crackdown threatens to drastically reduce the number of current and future workers for the industry. “People may be here on a green card, and they are afraid ICE is going to show up,” said Katie Smith Sloan, president of LeadingAge, an association of nonprofits that care for older adults.

Existing staffing shortages and quality-of-care problems would be compounded by other policies pushed by Trump and the Republican-led Congress, according to nursing home officials, resident advocates, and academic experts. Federal spending cuts under negotiation may strip nursing homes of some of their largest revenue sources by limiting ways states leverage Medicaid money and making it harder for new nursing home residents to retroactively qualify for Medicaid. Care for 6 in 10 residents is paid for by Medicaid, the state-federal health program for poor or disabled Americans.

“We are facing the collision of two policies here that could further erode staffing in nursing homes and present health outcome challenges,” said Eric Roberts, an associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The industry hasn’t recovered from covid-19, which killed more than 200,000 long-term care facility residents and workers and led to massive staff attrition and turnover. Nursing homes have struggled to replace licensed nurses, who can find better-paying jobs at hospitals and doctors’ offices, as well as nursing assistants, who can earn more working at big-box stores or fast-food joints. Quality issues that preceded the pandemic have expanded: The percentage of nursing homes that federal health inspectors cited for putting residents in jeopardy of immediate harm or death has risen alarmingly from 17% in 2015 to 28% in 2024.

In addition to seeking to reduce Medicaid spending, congressional Republicans have proposed shelving the biggest nursing home reform in decades: a Biden-era rule mandating minimum staffing levels that would require most of the nation’s nearly 15,000 nursing homes to hire more workers.

The long-term care industry expects demand for direct care workers to burgeon with an influx of aging baby boomers needing professional care. The Census Bureau has projected the number of people 65 and older would grow from 63 million this year to 82 million in 2050.

In an email, Vianca Rodriguez Feliciano, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, said the agency “is committed to supporting a strong, stable long-term care workforce” and “continues to work with states and providers to ensure quality care for older adults and individuals with disabilities.” In a separate email, Tricia McLaughlin, a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson, said foreigners wanting to work as caregivers “need to do that by coming here the legal way” but did not address the effect on the long-term care workforce of deportations of classes of authorized immigrants.

Goodwin Living, a faith-based nonprofit, runs three retirement communities in northern Virginia for people who live independently, need a little assistance each day, have memory issues, or require the availability of around-the-clock nurses. It also operates a retirement community in Washington, D.C. Medicare rates Goodwin House Alexandria as one of the best-staffed nursing homes in the country. Forty percent of the organization’s 1,450 employees are foreign-born and are either seeking citizenship or are already naturalized, according to Lindsay Hutter, a Goodwin spokesperson.

“As an employer, we see they stay on with us, they have longer tenure, they are more committed to the organization,” said Rob Liebreich, Goodwin’s president and CEO.

Jackline Conteh spent much of her youth shuttling between Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Ghana to avoid wars and tribal conflicts. Her mother was killed by a stray bullet in her home country of Liberia, Conteh said. “She was sitting outside,” Conteh, 56, recalled in an interview.

Conteh was working as a nurse in a hospital in Sierra Leone in 2009 when she learned of a lottery for visas to come to the United States. She won, though she couldn’t afford to bring her husband and two children along at the time. After she got a nursing assistant certification, Goodwin hired her in 2012.

Conteh said taking care of elders is embedded in the culture of African families. When she was 9, she helped feed and dress her grandmother, a job that rotated among her and her sisters. She washed her father when he was dying of prostate cancer. Her husband joined her in the United States in 2017; she cares for him because he has heart failure.

“Nearly every one of us from Africa, we know how to care for older adults,” she said.

Her daughter is now in the United States, while her son is still in Africa. Conteh said she sends money to him, her mother-in-law, and one of her sisters.

In the nursing home where Goodness and 89 other residents live, Conteh helps with daily tasks like dressing and eating, checks residents’ skin for signs of swelling or sores, and tries to help them avoid falling or getting disoriented. Of 102 employees in the building, broken up into eight residential wings called “small houses” and a wing for memory care, at least 72 were born abroad, Hutter said.

Donald Goodness grew up in Rochester, New York, and spent 25 years as rector of The Church of the Ascension in New York City, retiring in 1997. He and his late wife moved to Alexandria to be closer to their daughter, and in 2011 they moved into independent living at the Goodwin House. In 2023 he moved into one of the skilled nursing small houses, where Conteh started caring for him.

“I have a bad leg and I can’t stand on it very much, or I’d fall over,” he said. “She’s in there at 7:30 in the morning, and she helps me bathe.” Goodness said Conteh is exacting about cleanliness and will tell the housekeepers if his room is not kept properly.

Conteh said Goodness was withdrawn when he first arrived. “He don’t want to come out, he want to eat in his room,” she said. “He don’t want to be with the other people in the dining room, so I start making friends with him.”

She showed him a photo of Sierra Leone on her phone and told him of the weather there. He told her about his work at the church and how his wife did laundry for the choir. The breakthrough, she said, came one day when he agreed to lunch with her in the dining room. Long out of his shell, Goodness now sits on the community’s resident council and enjoys distributing the mail to other residents on his floor.

“The people that work in my building become so important to us,” Goodness said.

While Trump’s 2024 election campaign focused on foreigners here without authorization, his administration has broadened to target those legally here, including refugees who fled countries beset by wars or natural disasters. This month, the Department of Homeland Security revoked the work permits for migrants and refugees from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela who arrived under a Biden-era program.

“I’ve just spent my morning firing good, honest people because the federal government told us that we had to,” Rachel Blumberg, president of the Toby & Leon Cooperman Sinai Residences of Boca Raton, a Florida retirement community, said in a video posted on LinkedIn. “I am so sick of people saying that we are deporting people because they are criminals. Let me tell you, they are not all criminals.”

At Goodwin House, Conteh is fearful for her fellow immigrants. Foreign workers at Goodwin rarely talk about their backgrounds. “They’re scared,” she said. “Nobody trusts anybody.” Her neighbors in her apartment complex fled the U.S. in December and returned to Sierra Leone after Trump won the election, leaving their children with relatives.

“If all these people leave the United States, they go back to Africa or to their various countries, what will become of our residents?” Conteh asked. “What will become of our old people that we’re taking care of?”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

The post Dual Threats From Trump and GOP Imperil Nursing Homes and Their Foreign-Born Workers appeared first on kffhealthnews.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This content primarily highlights concerns about the impact of restrictive immigration policies and Medicaid spending cuts proposed by the Trump administration and Republican lawmakers on the long-term care industry. It emphasizes the importance of immigrant workers in healthcare, the challenges that staffing shortages pose to patient care, and the potential negative effects of GOP policy proposals. The tone is critical of these policies while sympathetic toward immigrant workers and advocates for maintaining or increasing government support for healthcare funding. The framing aligns with a center-left perspective, focusing on social welfare, immigrant rights, and concern about the consequences of conservative economic and immigration policies without descending into partisan rhetoric.

-

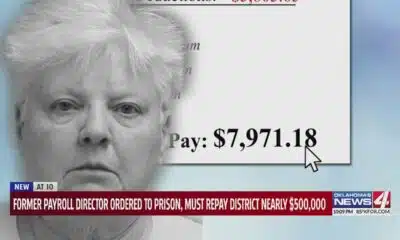

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed3 days ago

Former payroll director ordered to prison, must repay district nearly $500,000

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Two people unaccounted for in Spring Lake after flash flooding

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed5 days ago

Trump’s new tariffs take effect. Here’s how Tennesseans could be impacted

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed4 days ago

Jim Lovell, Apollo 13 moon mission leader, dies at 97

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

Man accused of running over Kansas City teacher with car before shooting, killing her

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed6 days ago

Tulsa, OKC Resort to Hostile Architecture to Deter Homeless Encampments

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed6 days ago

Why congressional redistricting is blowing up across the US this summer

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

Drugs, stolen vehicles and illegal firearms allegedly found in Slidell home