Ethan Miller/Getty Images

Danielle Wilhour, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

Cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF, is a clear, colorless liquid that plays a crucial role in maintaining the health and function of your central nervous system. It cushions the brain and spinal cord, provides nutrients and removes waste products.

Despite its importance, problems related to CSF often go unnoticed until something goes wrong.

Recently, cerebrospinal fluid disorders drew public attention with the announcement that musician Billy Joel had been diagnosed with normal pressure hydrocephalus. In this condition, excess CSF accumulates in the brain’s cavities, enlarging them and putting pressure on surrounding brain tissue even though diagnostic readings appear normal. Because normal pressure hydrocephalus typically develops gradually and can mimic symptoms of other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, it is often misdiagnosed.

I am a neurologist and headache specialist. In my work treating patients with CSF pressure disorders, I have seen these conditions present in many different ways. Here’s what happens when your cerebrospinal fluid stops working.

What is cerebrospinal fluid?

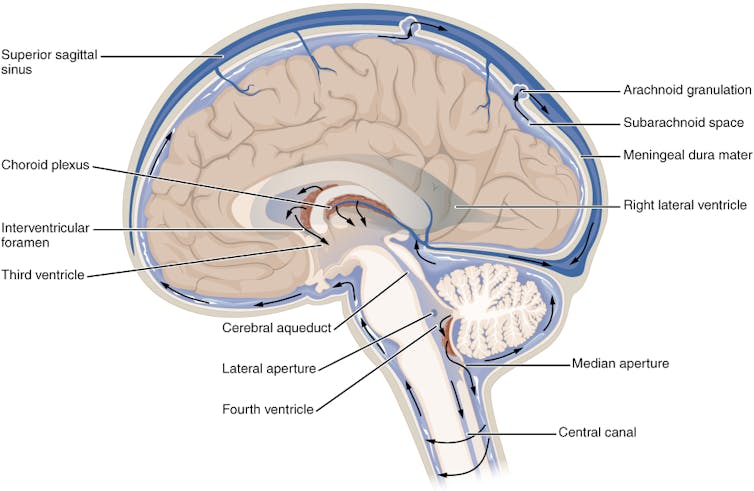

CSF is made of water, proteins, sugars, ions and neurotransmitters. It is primarily produced by a network of cells called the choroid plexus, which is located in the brain’s ventricles, or cavities.

The choroid plexus produces approximately 500 milliliters (17 ounces) of CSF daily, but only about 150 milliliters (5 ounces) are present within the central nervous system at any given time due to constant absorption and replenishment in the brain. This fluid circulates through the ventricles of the brain, the central canal of the spinal cord and the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

OpenStax, CC BY-SA

CSF has several critical functions. It protects the brain and spinal cord from injury by absorbing shocks. Suspending the brain in this fluid reduces its effective weight and prevents it from being crushed under its own mass. Additionally, CSF helps maintain a stable chemical environment in the central nervous system, facilitating the removal of metabolic waste and the distribution of nutrients and hormones.

If the production, circulation or absorption of cerebrospinal fluid is disrupted, it can lead to significant health issues. Two notable conditions are CSF leaks and idiopathic intracranial hypertension.

Cerebrospinal fluid leak

A CSF leak occurs when the fluid escapes through a tear or hole in the dura mater – the tough, outermost layer of the meninges that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

The dura can be damaged from head injuries or punctured during surgical procedures involving the sinuses, brain or spine, such as lumbar puncture, epidurals, spinal anesthesia or myelogram. Spontaneous CSF leaks can also occur without any identifiable cause.

CSF leaks were originally thought to be relatively rare, with an estimated annual incidence of 5 per 100,000 people. However, with increased awareness and advances in imaging, health care providers are discovering more and more leaks. They tend to occur more frequently in middle-aged adults and are more common in women than men.

Risk factors for the condition include connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome as well as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Unfortunately, it’s common for health care providers to misdiagnose a CSF leak as another condition, like migraine, sinus infections or allergies. What can make diagnosing a CSF leak challenging is its broad symptoms. Most people with a CSF leak have a positional headache that improves when lying down and worsens when standing. Pain is usually felt in the back of the head and may involve the neck and between the shoulder blades. In addition to headaches, patients may experience ringing in the ears, vision disturbances, memory problems, brain fog, dizziness and nausea.

Imaging may help guide diagnosis, including an MRI of your brain or entire spine, or a myelogram of the space surrounding your spinal cord. Features of a CSF leak that are visible in a scan include your brain sagging down in the base of your skull as well as a fluid collection outside of your dura. However, an estimated 19% of people with a CSF leak can have normal scans, so not seeing signs of a leak on imaging does not entirely rule it out.

Conservative treatment for a CSF leak involves rest, lying flat and increasing your fluid intake to give your spine time to heal the puncture. Increasing your caffeine consumption to an equivalent of three to four cups of coffee per day can also help by increasing CSF production through stimulating the choroid plexus. Caffeine also relieves pain by interacting with adenosine receptors, which are key players in the body’s pain perception mechanisms.

If a conservative approach is not successful, an epidural blood patch may be necessary. In this procedure, blood is drawn from your arm and injected into your spine. The injected blood can help form a covering over the hole and promote the healing process. Headache improvement can be fast, but if the patch does not work or the results are short-lived, additional testing may be needed to better locate the site of the leak. In rare cases, surgery may be recommended. Most patients with a CSF leak respond to some form of these treatments.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a disorder involving an excess of CSF that elevates pressure inside the skull and compresses the brain. The term “idiopathic” indicates that the cause of the raised pressure is unknown.

Most patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension have a history of obesity or recent weight gain. Other risk factors include taking certain medications such as tetracycline, excessive vitamin A, tretinoin, steroids and growth hormone. Middle-aged obese women are 20 times more likely to be diagnosed with idiopathic intracranial hypertension than other patient groups. As obesity becomes more prevalent, so too does the incidence of this condition.

Patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension typically experience headaches and vision changes, tinnitus or eye pain. Papilledema, or swelling of the optic disc, is the hallmark finding on a fundoscopic examination of the back of the eye. Clinicians may also observe paralysis of the patient’s eye muscles.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus, Joel’s diagnosis, is a form of this condition that commonly results in difficulty walking, loss of bladder control and cognitive impairment, sometimes referred to as the “wet, wobbly and wacky” triad. Joel’s diagnosis has brought awareness to this underrecognized but potentially treatable disorder, which is often managed through surgically placing a shunt to divert excess fluid and relieve symptoms.

Brain imaging of patients suspected of having idiopathic intracranial hypertension is crucial to excluding other causes of elevated CSF pressure, such as brain tumors or blood clots in the brain. A lumbar puncture or spinal tap to measure the pressure and composition of CSF is also central to diagnosis.

Since high intracranial pressure can damage the optic nerve and lead to permanent vision loss, the primary goal of treatment is to decrease pressure and preserve the optic nerve. Treatment options include weight loss, dietary changes and medications to reduce CSF production. Surgical procedures can also reduce intracranial pressure.

Future directions and unknowns

Cerebrospinal fluid is indispensable for brain health. Despite advances in understanding diseases related to CSF, several aspects remain unclear.

The exact mechanisms that lead to conditions like CSF leaks and idiopathic intracranial hypertension are not fully understood, though there are many theories. Further research is vital to enhance diagnostic accuracy and effective treatments for CSF disorders.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Aug. 14, 2024.

Danielle Wilhour, Assistant Professor of Neurology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.