Flavio Coelho/Moment via Getty Images

Courtney Gibbons, Hamilton College

You scrambled up a Rubik’s cube, and now you want to put it back in order. What sequence of moves should you make?

Surprise: You can answer this question with modern algebra.

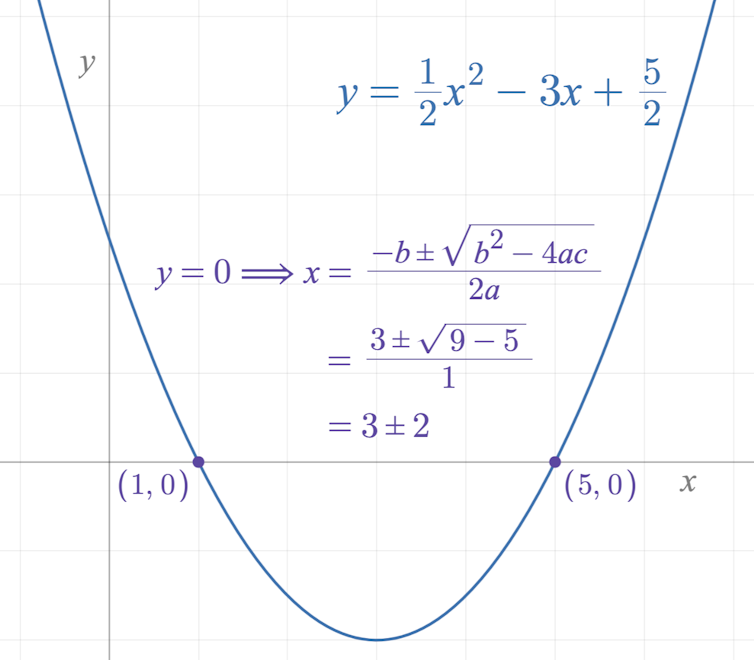

Most folks who have been through high school mathematics courses will have taken a class called algebra – maybe even a sequence of classes called algebra I and algebra II that asked you to solve for x. The word “algebra” may evoke memories of complicated-looking polynomial equations like ax² + bx + c = 0 or plots of polynomial functions like y = ax² + bx + c.

You might remember learning about the quadratic formula to figure out the solutions to these equations and find where the plot crosses the x-axis, too.

Jacob Rus, CC BY-SA

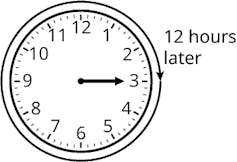

Equations and plots like these are part of algebra, but they’re not the whole story. What unifies algebra is the practice of studying things – like the moves you can make on a Rubik’s cube or the numbers on a clock face you use to tell time – and the way they behave when you put them together in different ways. What happens when you string together the Rubik’s cube moves or add up numbers on a clock?

In my work as a mathematician, I’ve learned that many algebra questions come down to classifying objects by their similarities.

Sets and groups

How did equations like ax² + bx + c = 0 and their solutions lead to abstract algebra?

The short version of the story is that mathematicians found formulas that looked a lot like the quadratic formula for polynomial equations where the highest power of x was three or four. But they couldn’t do it for five. It took mathematician Évariste Galois and techniques he developed – now called group theory – to make a convincing argument that no such formula could exist for polynomials with a highest power of five or more.

So what is a group, anyway?

It starts with a set, which is a collection of things. The fruit bowl in my kitchen is a set, and the collection of things in it are pieces of fruit. The numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 also form a set. Sets on their own don’t have too many properties – that is, characteristics – but if we start doing things to the numbers 1 through 12, or the fruit in the fruit bowl, it gets more interesting.

OpenStax, CC BY-SA

Let’s call this set of numbers 1 through 12 “clock numbers.” Then, we can define an addition function for the clock numbers using the way we tell time. That is, to say “3 + 11 = 2” is the way we would add 3 and 11. It feels weird, but if you think about it, 11 hours past 3 o’clock is 2 o’clock.

Clock addition has some nice properties. It satisfies:

- closure, where adding things in the set gives you something else in the set,

- identity, where there’s an element that doesn’t change the value of other elements in the set when added – adding 12 to any number will equal that same number,

- associativity, where you can add wherever you want in the set,

- inverses, where you can undo whatever an element does, and

- commutativity, where you can change the order of which clock numbers you add up without changing the outcome: a + b = b + a.

By satisfying all these properties, mathematicians can consider clock numbers with clock addition a group. In short, a group is a set with some way of combining the elements layered on top. The set of fruit in my fruit bowl probably can’t be made into a group easily – what’s a banana plus an apple? But we can make a set of clock numbers into a group by showing that clock addition is a way of taking two clock numbers and getting to a new one that satisfies the rules outlined above.

Rings and fields

Along with groups, the two other fundamental types of algebraic objects you would study in an introduction to modern algebra are rings and fields.

We could introduce a second operation for the clock numbers: clock multiplication, where 2 times 7 is 2, because 14 o’clock is the same as 2 o’clock. With clock addition and clock multiplication, the clock numbers meet the criteria for what mathematicians call a ring. This is primarily because clock multiplication and clock addition together satisfy a key component that defines a ring: the distributive property, where a(b + c) = ab + ac. Lastly, fields are rings that satisfy even more conditions.

At the turn of the 20th century, mathematicians David Hilbert and Emmy Noether – who were interested in understanding how the principles in Einstein’s relativity worked mathematically – unified algebra and showed the utility of studying groups, rings and fields.

It’s all fun and games until you do the math

Groups, rings and fields are abstract, but they have many useful applications.

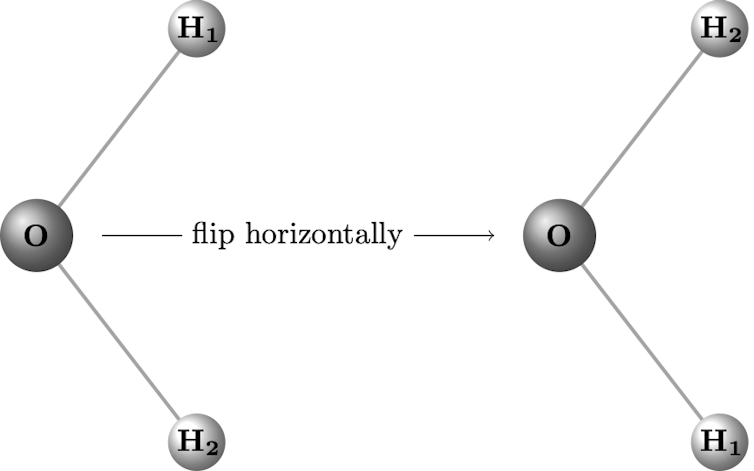

For example, the symmetries of molecular structures are categorized by different point groups. A point group describes ways to move a molecule in space so that even if you move the individual atoms, the end result is indistinguishable from the molecule you started with.

Courtney Gibbons, CC BY-SA

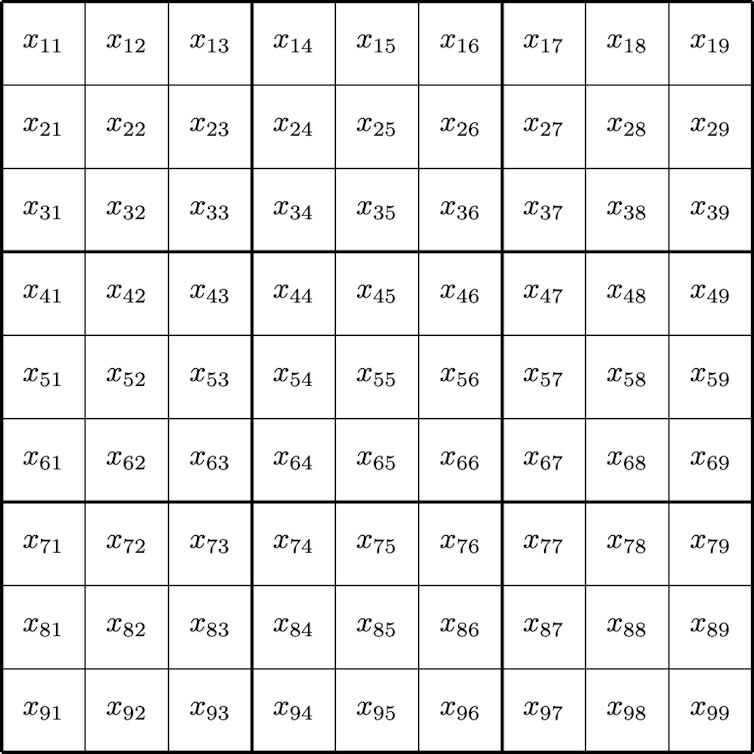

But let’s take a different example that uses rings instead of groups. You can set up a pretty complicated set of equations to describe a Sudoku puzzle: You need 81 variables to represent each place you can put a number in the grid, polynomial expressions to encode the rules of the game, and polynomial expressions that take into account the clues already on the board.

To get the spaces on the game board and the 81 variables to correspond nicely, you can use two subscripts to associate the variable with a specific place on the board, like using x₃₅ to represent the cell in the third row and fifth column.

The first entry must be one of the numbers 1 through 9, and we represent that relationship with (x₁₁ – 1)(x₁₁ – 2)(x₁₁ – 3) ⋅⋅⋅ (x₁₁ – 9). This expression is equal to zero if and only if you followed the rules of the game. Since every space on the board follows this rule, that’s already 81 equations just to say, “Don’t plug in anything other than 1 through 9.”

The rule “1 through 9 each appear exactly once in the top row” can be captured with some sneaky pieces of algebraic thinking. The sum of the top row is going to add up to 45, which is to say x₁₁ + x₁₂ + ⋅⋅⋅ + x₁₉ – 45 will be zero, and the product of the top row is going to be the product of 1 through 9, which is to say x₁₁ x₁₂ ⋅⋅⋅ x₁₉ – 9⋅8⋅7⋅6⋅5⋅4⋅3⋅2⋅1 will be zero.

If you’re thinking that it takes more time to set up all these rules than it does to solve the puzzle, you’re not wrong.

Courtney Gibbons

What do we get by doing this complicated translation into algebra? Well, we get to use late-20th century algorithms to figure out what numbers you can plug into the board that satisfy all the rules and all the clues. These algorithms are based on describing the structure of the special ring – called an ideal – these game board clues make within the larger ring. The algorithms will tell you if there’s no solution to the puzzle. If there are multiple solutions, the algorithms will find them all.

This is a small example where setting up the algebra is harder than just doing the puzzle. But the techniques generalize widely. You can use algebra to tackle problems in artificial intelligence, robotics, cryptography, quantum computing and so much more – all with the same bag of tricks you’d use to solve the Sudoku puzzle or Rubik’s cube.

Courtney Gibbons, Associate Professor of Mathematics, Hamilton College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.