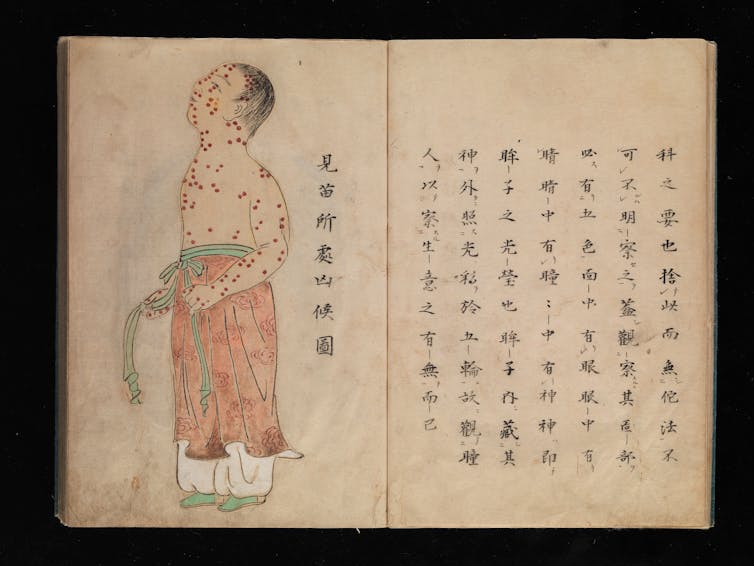

Toxoplasma is often transmitted to people from contaminated food or cat feces.

Bill Sullivan, Indiana University

Parasites take an enormous toll on human and veterinary health. But researchers may have found a way for patients with brain disorders and a common brain parasite to become frenemies.

A new study published in Nature Microbiology has pioneered the use of a single-celled parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, to inject therapeutic proteins into brain cells. The brain is very picky about what it lets in, including many drugs, which limits treatment options for neurological conditions.

As a professor of microbiology, I’ve dedicated my career to finding ways to kill dangerous parasites such as Toxoplasma. I’m fascinated by the prospect that we may be able to use their weaponry to instead treat other maladies.

Microbes as medicine

Ever since scientists realized that microscopic organisms can cause illness – what’s called the 19th-century germ theory of disease – humanity has been on a quest to keep infectious agents out of our bodies. Many people’s understandable aversion to germs may make the idea of adapting these microbial adversaries for therapeutic purposes seem counterintuitive.

But preventing and treating disease by co-opting the very microbes that threaten us has a history that long predates germ theory. As early as the 1500s, people in the Middle East and Asia noted that those lucky enough to survive smallpox never got infected again. These observations led to the practice of purposefully exposing an uninfected person to the material from an infected person’s pus-filled sores – which unbeknownst to them contained weakened smallpox virus – to protect them from severe disease.

The concept of inoculation developed with smallpox outbreaks several centuries ago.

This concept of inoculation has yielded a plethora of vaccines that have saved countless lives.

Viruses, bacteria and parasites have also evolved many tricks to penetrate organs such as the brain and could be retooled to deliver drugs into the body. Such uses could include viruses for gene therapy and intestinal bacteria to treat a gut infection known as C. diff.

Why can’t we just take a pill for brain diseases?

Pills offer a convenient and effective way to get medicine into the body. Chemical drugs such as aspirin or penicillin are small and easily absorbed from the gut into the bloodstream.

Biologic drugs such as insulin or semaglutide, on the other hand, are large and complex molecules that are vulnerable to breaking down in the stomach before they can be absorbed. They are also too big to pass through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream.

All drugs, especially biologics, have great difficulty penetrating the brain due to the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier is a layer of cells lining the brain’s blood vessels that acts like a gatekeeper to block germs and other unwanted substances from gaining access to neurons.

Toxoplasma offers delivery service to brain cells

Toxoplasma parasites infect all animals, including humans. Infection can occur in multiple ways, including ingesting spores released in the stool of infected cats or consuming contaminated meat or water. Toxoplasmosis in otherwise healthy people produces only mild symptoms but can be serious in immunocompromised people and to gestating fetusus.

Unlike most pathogens, Toxoplasma can cross the blood-brain barrier and invade brain cells. Once inside neurons, the parasite releases a suite of proteins that alter gene expression in its host, which may be a factor in the behavioral changes it causes in infected animals and people.

In a new study, a global team of researchers hijacked the system Toxoplasma uses to secrete proteins into its host cell. The team genetically engineered Toxoplasma to make a hybrid protein, fusing one of its secreted proteins to a protein called MeCP2, which regulates gene activity in the brain – in effect, giving the MeCP2 a piggyback ride into neurons. Researchers found that the parasites secreted the MeCP2 protein hybrid into neurons grown in a petri dish as well as in the brains of infected mice.

A genetic deficiency in MECP2 causes a rare brain development disorder called Rett syndrome. Gene therapy trials using viruses to deliver the MeCP2 protein to treat Rett syndrome are underway. If Toxoplasma can deliver a form of MeCP2 protein into brain cells, it may provide another option to treat this currently incurable condition. It also may offer another treatment option for other neurological problems that arise from errant proteins, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

The long road ahead

The road from laboratory bench to bedside is long and filled with obstacles, so don’t expect to see engineered Toxoplasma in the clinic anytime soon.

The obvious complication in using Toxoplasma for medical purposes is that it can produce a serious, lifelong infection that is currently incurable. Infecting someone with Toxoplasma can damage critical organ systems, including the brain, eyes and heart.

However, up to one-third of people worldwide currently carry Toxoplasma in their brain, apparently without incident. Emerging studies have correlated infection with increased risk of schizophrenia, rage disorder and recklessness, hinting that this quiet infection may be predisposing some people to serious neurological problems.

The widespread prevalence of Toxoplasma infections may also be another complication, as it disqualifies many people from using it for treatment. Since the billions of people who already carry the parasite have developed immunity against future infection, therapeutic forms of Toxoplasma would be rapidly destroyed by their immune systems once injected.

In some cases, the benefits of using Toxoplasma as a drug delivery system may outweigh the risks. Engineering benign forms of this parasite could produce the proteins patients need without harming the organ – the brain – that defines who we are.

Bill Sullivan, Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.