Mississippi Today

Big Companies Cashed In on Mississippi’s Water. Small Towns Paid the Price.

Sarah Fowler is reporting on the water crisis in Jackson, Miss., in the state where she was born and raised, as part of The Times’s Local Investigations Fellowship.

In winter 2021, more than 150,000 people living in Jackson, Miss., were left without running water.

Faucets were dry or dribbling a muddy brown. For weeks, people across the city lost the water they normally relied on to drink, cook and bathe. With no way to flush their toilets, some parents sent their children into the woods to relieve themselves. Businesses closed. Mississippi’s capital effectively shut down.

The following year, at the height of Mississippi’s sweltering summer in August 2022, it would all happen again.

Each time Jackson faced a water crisis, local and state leaders cast blame in familiar directions. Lawmakers criticized city officials for ignoring leaky pipes and failing to collect payments from customers. City officials pointed to Jackson’s shrinking population and decades of economic decline. And they said state officials, mostly white and Republican, had starved the mostly Black, Democratic city of resources.

But the final blow was delivered by Siemens, a giant German corporation that had swept into town in 2010, boldly promising to install modern water meters that would boost revenues and return Jackson’s water system to a moneymaking enterprise that could afford to fix its crumbling infrastructure.

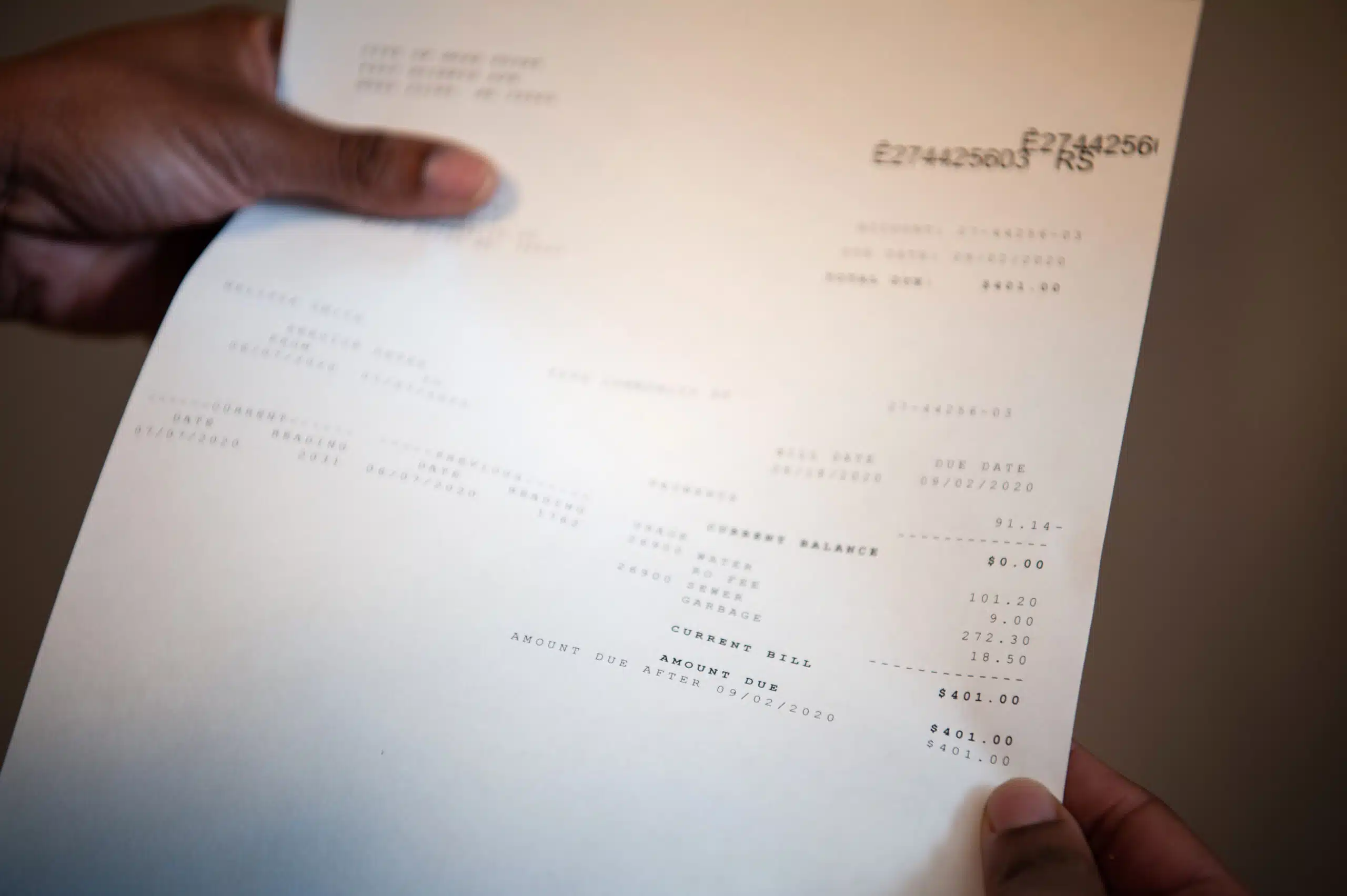

Siemens, better known for building power plants and high-speed trains, failed to deliver on its promises. Jackson found itself with many meters that didn’t work and wildly inaccurate water bills it couldn’t collect.

Siemens returned the $90 million it had been paid for the project. But the damage was done. Jackson was out more than $450 million in fees and lost revenue. It had no way to repair failing equipment and aging pipes that left city water unsafe to drink and ultimately led to a federal takeover of the water system in December 2022.

The outlines of Siemens’s role in Jackson’s water issues were laid out publicly in 2019, when the city sued the company. But Jackson was not the only Mississippi city that fell victim to the promise of easy money.

A yearlong New York Times investigation, drawing on thousands of pages of government records and interviews with city officials across the state, reveals how Siemens and other corporations went from one small, cash-strapped town to the next making grand promises to modernize water systems and boost revenues. It also sheds new light on the involvement of a state agency that was supposed to vet the deals.

In town after town, salesmen lured city officials who had little expertise in water meters with gee-whiz technology and complicated cost-saving algorithms. They said the meters could be installed at no cost to taxpayers and offered cash-back guarantees.

Even when meters started failing in large numbers and cities complained they were on the verge of financial disaster, the companies kept selling their services.

For nearly a decade, three companies — Siemens; the Mississippi-based McNeil Rhoads, started by a former Siemens salesman, Chris McNeil; and the North Carolina water meter manufacturer Mueller — crisscrossed the state signing multimillion-dollar deals in cities desperate for money.

Mr. McNeil pitched most of the deals, first for Siemens, then for his own company. He claimed that Mueller’s “smart” meters would be so accurate and efficient they would more than pay for themselves. In accordance with state policy at the time, every project was reviewed by the Mississippi Development Authority, an agency run by executives appointed by the governor.

From 2009 to 2017, at least 10 Mississippi cities signed contracts with the companies to install smart meters or other new technology. All but one have reported problems, and at least four have sued to recoup money they paid to Siemens, McNeil Rhoads or Mueller. Three of those suits are still pending.

Siemens and McNeil Rhoads, competitors that pitched the projects and acted as project managers, hired contractors who installed many meters improperly, according to officials in Jackson, McComb and Moss Point. In some cities, the two companies also struggled to link meters to the home office or to merge a new billing system with an old one.

Officials in at least eight Mississippi cities said they had problems with Mueller’s smart meters, which sometimes didn’t measure accurately because of faulty parts or batteries that died sooner than promised. Water departments in other states, including California and Missouri, have reported similar problems with Mueller meters over the past decade.

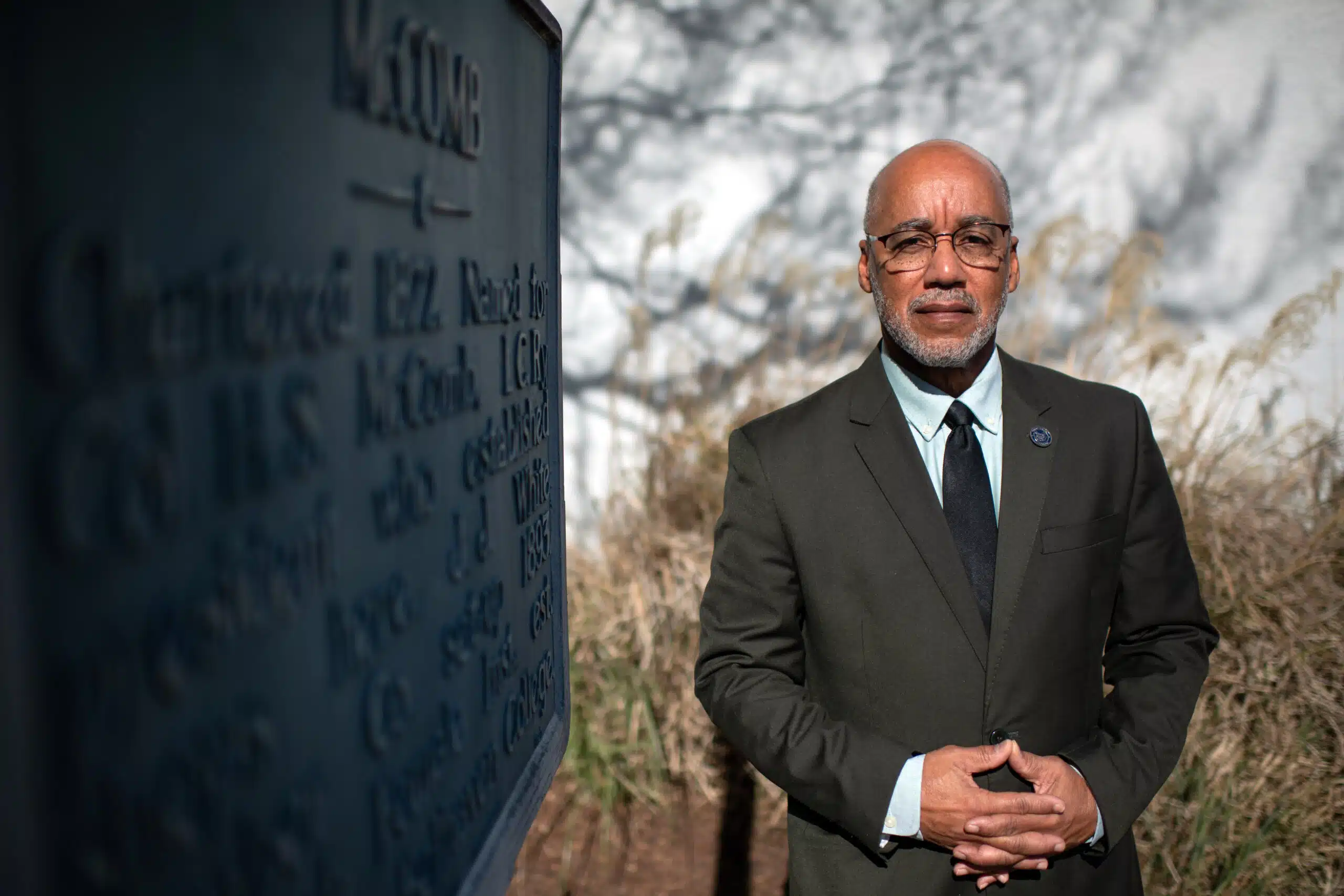

McComb, a city of 12,000 people south of Jackson, signed the first Siemens water meter contract in Mississippi. Mayor Quordiniah N. Lockley, city manager at the time, said McComb agreed to pay the company $10 million to install 6,000 smart Master Meters.

But contract workers hired by Siemens put them in backward and missed deadlines to install the antennas that the meters needed to communicate with a central office, Mr. Lockley said. Then some customers saw their water bills hit as much as $1,000 per month, with no obvious explanation.

Mr. Lockley said he called a friend, whom he declined to name, on the Jackson City Council and warned him not to go forward with the developing Siemens deal there.

He said he had one message: “Run.”

“Just because they come in a suit and tie doesn’t mean they’re not selling snake oil,” Mr. Lockley said in an interview.

Even as lawsuits and complaints from customers mounted, the companies continued making the same promises, and state and city officials continued approving contracts.

Jackson ultimately signed a deal with Siemens to install Mueller meters, the largest contract in the city’s history. Officials in Cleveland, a small city in the Mississippi Delta, inked a deal with Siemens for Mueller meters as well. Columbus, Meridian and Moss Point — all largely Black cities of fewer than 35,000 people — hired McNeil Rhoads to install Mueller meters.

Officials in some of the cities say they have been financially crippled.

In a letter to the development authority and the state attorney general, Jamie Lee, the city attorney for Cleveland, wrote that hundreds of meters were malfunctioning and the issue “could lead Cleveland into a major financial deficit if not addressed immediately.” She asked for “the assistance of your two offices in achieving a resolution with Siemens.”

Ms. Lee said she never received a response.

In a statement that did not address complaints by other Mississippi cities, a Siemens spokeswoman, Annie Satow, said the company had invested significant work in Jackson to “help navigate persistent challenges outside the company’s control,” including “substantial assistance beyond contractual requirements” with the billing system.

“Siemens acted in good faith, worked cooperatively with city personnel and was transparent and responsive to oversight by the city’s administration and Department of Public Works,” she wrote.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba of Jackson said that while he couldn’t discuss the specifics of the deal, Siemens was not entirely to blame. Jackson, he said, willingly entered into a bad agreement. He declined to elaborate, and his office did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. Since the federal takeover, which came with an infusion of $600 million and a third-party manager to run the water system, leaks are being repaired and citywide boil-water notices have drastically diminished.

Mr. McNeil did not return numerous calls seeking comment. A Mueller spokesman and other executives did not respond to repeated calls and emails.

Records show that Siemens and Mueller made attempts to replace or repair some meters in the cities where problems arose, but the cites still lost money and some, including Jackson, McComb and Moss Point, had to pay to replace meters or other technology on their own.

Reached by phone, Glenn McCullough, executive director of the Mississippi Development Authority from 2015 to 2020, said he had not been aware of widespread problems with Siemens, McNeil Rhoads or Mueller. He referred questions to the agency’s spokeswoman, Tammy Craft, who declined to comment.

“We can’t speak on this any further, since no one involved in reviewing these contracts back-when is at M.D.A. anymore,” Ms. Craft wrote.

But she noted that in 2017, state lawmakers passed a bill ending M.D.A.’s oversight of such contracts.

A promising solution for an ailing system

At the time Jackson was considering a deal with Siemens, the water industry was in the midst of a major transition. New technologies had made it possible for sensors to more accurately measure water use. Smart meters could eliminate the need for meter readers to visit homes to calculate people’s water bills, a huge potential savings for utility departments.

Manufacturers, including Mueller, saw the technology as a critical part of their future. But only if they could convince municipal water departments it was worth spending millions of dollars to replace old equipment. In financial statements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2015, Mueller described water utilities as slow adopters of the technology because of installation costs.

The water industry found a solution in the growing effort to make public agencies and schools more energy-efficient.

As far back as the 1980s, the federal government had been supporting partnerships with private companies to retrofit buildings with more efficient equipment.

Under energy performance contracts, municipalities could borrow money and use it to hire private contractors to replace old light fixtures, air-conditioning units and other appliances. Savings from lower electric bills would then be used to pay off the debt, allowing cities to invest in improvements at no real cost to taxpayers.

The contracts had made Siemens tens of millions of dollars in Mississippi alone and allowed a financially struggling state to afford equipment upgrades that otherwise might have been out of reach.

Then, two years before Siemens pitched a plan to help Jackson fix its ailing water system, the Mississippi attorney general’s office issued an opinion that helped pave the way for even more ambitious projects.

In 2008, the office reviewed the state statute governing energy performance contracts and concluded that cities and school districts could use them to finance projects that conserved water, not just energy.

An opportunity ‘too good to pass up’

In 2009, a decade before Jackson officials sued Siemens over failed meters, the company signed its first water contract in the state in tiny McComb.

McComb had boomed as a railroad city in the 1870s, carved out of a dense pine forest about halfway between Jackson and New Orleans.

Today it resembles a lot of small Mississippi towns: Its shrinking population is almost 75 percent Black. One in three people live under the poverty line. A downtown resurgence has begun, but money for civic improvements is in short supply.

So when Siemens offered a way to fill city coffers through the water department, the opportunity seemed too good to pass up.

According to Mr. Lockley, Siemens told city officials they would be able to disconnect someone’s water with the touch of a button while sitting in their office. New smart meters would measure water use remotely and more accurately.

Siemens said the meters would boost revenues by more than $600,000 a year, sales materials show. And city officials believed McComb would be “one of the top water departments in the state,” Mr. Lockley recalled.

McComb paid Siemens to replace 6,000 water meters, but computer software glitches and delays in installing communication antennae left the city unable to monitor water usage remotely, Mr. Lockley said. Residents also began complaining of erroneous water bills.

When McComb tried to cancel the contract, Siemens sued and the case went to mediation. To get out of the contract, McComb agreed to pay for the meters already in the ground at a cost of $2 million to $3 million, Mr. Lockley said. Then the city hired another company to install software that allowed the meters to function.

Mr. Lockley said he has never spoken publicly about the settlement before because he signed a nondisclosure agreement.

“They tie your hands, say you can’t talk about the situation, and it just keeps happening,” Mr. Lockley said.

Jackson’s crippling ‘sweetheart deal’

Even as problems arose in McComb, Mr. McNeil used the city as a selling point to win new business for Siemens.

Mr. McNeil had been a local football standout in Petal, Miss., before becoming an offensive lineman at Mississippi State University in the early 2000s. He previously had secured a 15-year contract for Siemens to overhaul lighting, air-conditioning and traffic lights throughout Jackson.

He and a fellow salesman, Dusty Rhoads, the son of the mayor of nearby Flowood, traveled the state, pitching similar contracts to financially strapped towns. They eventually left Siemens and started their own company, McNeil Rhoads, signing smart meter contracts with at least six cities.

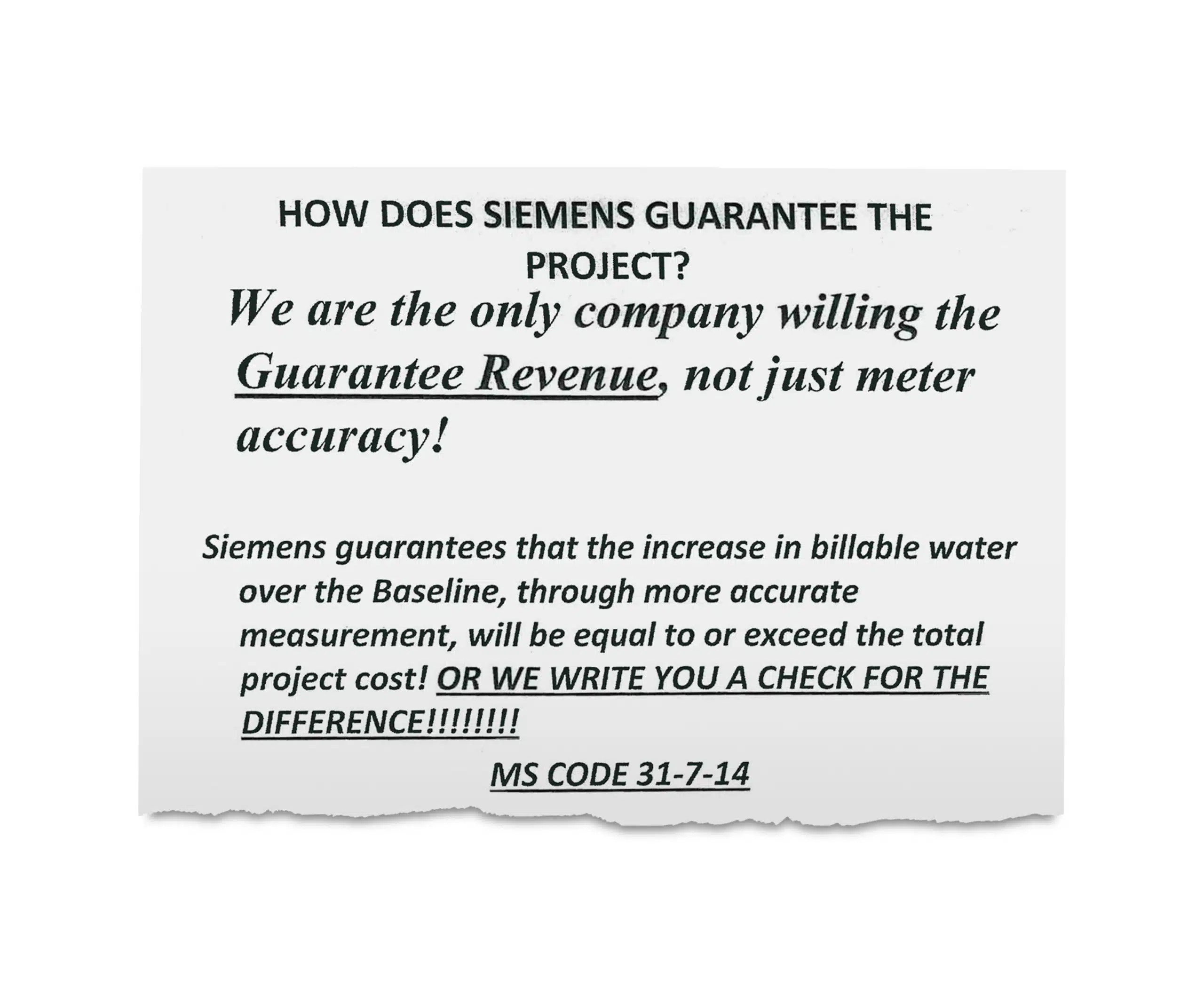

When pitching to Cleveland, Mr. McNeil, representing Siemens, noted the McComb contract in a sales presentation, city records show. Savings were “guaranteed,” his slide show said. If they fell short, “we will write you a check for the difference.” The statement was followed by eight exclamation points.

In September 2010, Mr. McNeil sent the first in a series of emails to the Public Works Department in Jackson. He had a plan to replace the city’s water meters and make critical repairs to its infrastructure. The project would create jobs, he promised, and the new meters would cover the cost of installation — or else the company would.

Mr. McNeil pursued Jackson officials for two years and backed up his cost-saving claims with a Siemens-funded study of the meters. All of this, he said, had already been done down the road in McComb.

By the end of 2012, Jackson was on the verge of signing a $90 million deal that the city would later estimate cost it $450 million in expenses and lost revenues.

Based on an email Mr. McNeil sent to Jackson’s public works director then, Dan Gaillet, at least one Jackson official was aware of the project in McComb. But Mr. Lockley said no one called him about it and his warning was ignored.

Problems emerged just weeks into the Jackson project. A politically connected subcontractor, hired by Siemens at the recommendation of city officials, had installed some meters improperly, and later, there were communication errors between the meters and receivers. Some meters showed customers not using any water, while others got huge bills that city officials said were implausible.

Unable to calculate realistic bills, Jackson officials stopped collecting from thousands of customers.

The loss of revenue exacerbated years of neglect and poor decision-making and left the water department in dire financial straits and residents facing a near continuous string of boil-water notices. City officials would later accuse subcontractors involved with the project of contributing to the problems, something they deny.

A former Jackson councilman, Melvin Priester, was elected after the city had signed the deal but before groundbreaking had begun. He voiced his objections but was in the minority.

Siemens got a “sweetheart deal,” Mr. Priester told The Times, but “when you are in bad straits like the City of Jackson is now and was in 2013, all of your options are bad deals.”

Calls for help went unanswered

The Mississippi Development Authority, which greenlit the project, was created in 2000 as an economic engine for the state. It directs tax credits to attract companies and gives out millions of dollars in grants to spur revitalization efforts.

As far back as 2010, it also played a role in reducing local energy and water use.

If a city wanted to borrow against future savings for a retrofit project, it had to submit a request to the development authority. State law required the authority to review and approve each contract to “assure that entities can rely upon projected and guaranteed energy savings,” according to policies that were in effect until 2017.

The reviews, conducted by licensed engineers outside the authority, were seen as a critical backstop by city officials, who often lacked the expertise or resources to verify companies’ promises.

“M.D.A. legitimized it,” said Amy St. Pe’, Moss Point’s city attorney, who is suing McNeil Rhoads and Mueller. “Any doubts that we had, when we saw that M.D.A. was backing the program, we felt that it had to be good for the city.”

During a sales pitch, Mr. McNeil cited the agency’s approval process to dispel naysayers in Harrison County, a Gulf Coast community that was considering a project with his company. At a September 2014 meeting, the board of supervisors worried that the county could be left millions in debt if the savings didn’t pan out, according to an article in The Biloxi Sun Herald. Mr. McNeil responded by saying the project was “100 percent regulated by the Mississippi Development Authority,” and the board voted unanimously in favor.

Records show the agency often engaged in back-and-forth with cities seeking approval of the contracts. No application prompted more scrutiny than Jackson’s.

When the development authority reviewed Siemens’s proposal, it raised more than 200 questions, asking how the work being described could possibly save the city money. Mayor Harvey Johnson Jr. sent a 19-page reply that answered and largely dismissed those concerns. One week later, in March 2013, the agency signed off on the contract.

From 2009 to 2017, at least 12 cities pursued energy performance contracts that the agency reviewed, a number of them involving water projects.

Companies pitching the work came up with predicted cost savings using their own methods, records show. Siemens’s estimate, for example, depended largely on how much more accurate new meters would be than old meters. But nowhere in the state’s analysis did engineers ask Siemens or the other companies to prove their calculations.

In a review of hundreds of pages of correspondence between the agency and local officials, The Times did not find a single instance when state officials passed on information about problems cities were experiencing with Siemens, McNeil Rhoads or Mueller.

In fact, when cities directly reported problems and begged the agency for help, they found themselves on their own.

Ms. Lee, the Cleveland city attorney, said she, the mayor and at least two aldermen sought guidance from the agency to no avail.

Ms. Lee wrote her letter in May 2018. A year later, in August 2019, when the city was already embroiled in a lawsuit with Siemens and Mueller, Alderman Gary Gainspoletti sent another letter, pleading with officials as the city was trying to “stop the bleeding.”

An agency official acknowledged receipt, but help never came.

Mr. McCullough, the agency’s executive director at the time, said, “I don’t recall seeing any document regarding defective water meters coming to my desk.”

Warning signs emerge nationwide

For years as companies installed Mueller meters across Mississippi, the meter manufacturer was aware of problems with its products in other states, including California and Missouri.

In 2012, the same year Cleveland was putting faulty water meters in the ground and Jackson was signing its contract, Mueller alerted a water authority in Missouri that some meters had defective magnets that would break, preventing them from recording water consumption, according to a regulatory report. The water authority returned the meters to Mueller for repair.

Years later, a federal class action lawsuit filed in New York by a Mueller shareholder alleged that executives had “misled the investing public” by not being honest about the failure rate of smart meters. The suit was dismissed in 2020, but sworn statements by three confidential informants suggested that Mueller was struggling with high failure rates as early as 2013.

That is when San Diego officials realized that a connection problem was preventing many of the meters from recording data, according to one of the witnesses, described in the suit as a regional manager for Mueller. Residents complained for years of abnormally high bills. The same issues would arise in Jackson and other Mississippi cities.

The suit also pointed out problems that year in Missouri. Mueller replaced nearly 80 percent of water meters in Chillicothe after moisture was found in parts that were supposed to be dry. By 2019, because of battery issues, the replacement meters had a failure rate of 89 percent.

The largest investigation into Mueller by a public utility would unfold in the state. From 2012 to 2015, Missouri American Water installed thousands of Mueller meters. Regulators reported that the meters had “several different kinds of defects,” leading to inaccurate readings or none at all. In August 2015, the utility began a costly campaign to replace 24,000 of the nearly 100,000 that had been installed.

All the while, Mueller was touting its smart meters as a critical driver of growth and telling investors that municipal governments would increasingly seek out the new technology.

‘They preyed on disadvantaged cities’

Mr. McNeil continued to push Mueller meters. After winning Siemens the Jackson contract, he started his own company and used the meters in energy performance contracts he landed across Mississippi — in Columbus, Gautier, Grenada, Meridian, Moss Point and Tupelo.

Seven years after signing in 2014, Columbus Light and Water Department reported excessive failure rates and began pressing Mueller to make good on an extended warranty it had promised. Early on, the company was responsive, answering emails and sending a batch of parts, according to department records. But when complaints continued, Mueller employees stopped answering the department’s questions, said Mike Bernsen, the utility’s interim general manager in 2021.

“We played it through the channels as far as we could.” Mr. Bernsen said.

Frustrations with getting Mueller officials to respond continued into 2022, emails show. In a series of emails early that year, department officials asked Mueller for a meeting to discuss the increasing number of failing meters, but after weeks without an answer, they concluded the company was avoiding them.

Moss Point, signing with McNeil Rhoads in 2017, discovered problems almost immediately, according to Ms. St. Pe’, the city attorney. Residents’ bills were improbably high, and Mueller initially offered batches of replacement devices.

But then, once the city filed suit, the company claimed it was under no obligation to replace the meters because the city had bought them from McNeil Rhoads, not directly from Mueller. Mueller stopped responding and McNeil Rhoads went out of business, leaving Moss Point with little financial recourse, Ms. St. Pe’ said.

“McNeil Rhoades is who convinced us to purchase these water meters,” she said. “I feel like they preyed on disadvantaged cities, predominantly African American cities.”

Out of the six known cities that hired McNeil Rhoads, four are majority Black.

Mueller may have stopped replying to Columbus and Moss Point, but a sales representative, John Flynn, was still pushing updated meters in Tupelo last June.

In an email to Chris Lewis, the local utility’s superintendent, he asked if the city wanted to “try some of our new meters.” Mr. Lewis said he would take five. Mr. Flynn said they come eight to a box.

Mr. Lewis responded: “Perfect!”

Irene Casado Sanchez contributed reporting. This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.biloxinewsevents.com/?p=328531

Mississippi Today

PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership

NEW ALBANY — After five hours in a courtroom where attendees struggled to find standing room, the Mississippi Public Service Commission voted to petition a judge to put the Holly Springs Utility Department into a receivership.

The PSC held the hearing Thursday about a half hour drive west from Holly Springs in New Albany, known as “The Fair and Friendly City.” Throughout the proceedings, members of the PSC, its consultants and Holly Springs officials emphasized there was no precedent for what was going on.

The city of Holly Springs has provided electricity through a contract with the Tennessee Valley Authority since 1935. It serves about 12,000 customers, most of whom live outside the city limits. While current and past city officials say the utility’s issues are a result of financial negligence over many years, the service failures hit a boiling point during a 2023 ice storm where customers saw outages that lasted roughly two weeks as well as power surges that broke their appliances.

Those living in the service area say those issues still occur periodically, in addition to infrequent and inaccurate billing.

“I moved to Marshall County in 2020 as a place for retirement for my husband and I, and it’s been a nightmare for five years,” customer Monica Wright told the PSC at Thursday’s hearing. “We’ve replaced every electronic device we own, every appliance, our well pump and our septic pumps. It has financially broke us.

“We’re living on prayers and promises, and we need your help today.”

Another customer, Roscoe Sitgger of Michigan City, said he recently received a series of monthly bills between $500 and $600.

Following a scathing July report by Silverpoint Consulting that found Holly Springs is “incapable” of running the utility, the three-member PSC voted unanimously on Thursday to determine the city isn’t providing “reasonably adequate service” to its customers. That language comes from a 2024 state bill that gave the commission authority to investigate the utility.

The bill gives a pathway for temporarily removing the utility’s control from the city, allowing the PSC to petition a chancery judge to place the department into the hands of a third party. The PSC voted unanimously to do just that.

Thursday’s hearing gave the commission its first chance to direct official questions at Holly Springs representatives. Newly elected Mayor Charles Terry, utility General Manager Wayne Jones and City Attorney John Keith Perry fielded an array of criticism from the PSC. In his rebuttal, Perry suggested that any solution — whether a receivership or selling the utility — would take time to implement, and requested 24 months for the city to make incremental improvements. Audience members shouted, “No!” as Perry spoke.

“We are in a crisis now,” responded Northern District Public Service Commissioner Chris Brown. “To try to turn the corner in incremental steps is going to be almost impossible.”

It’s unclear how much it would cost to fix the department’s long list of ailments. In 2023, TVPPA — a nonprofit that represents TVA’s local partners — estimated Holly Springs needs over $10 million just to restore its rights-of-way, and as much as $15 million to fix its substations. The department owes another $10 million in debt to TVA as well as its contractors, Brown said.

“The city is holding back the growth of the county,” said Republican Sen. Neil Whaley of Potts Camp, who passionately criticized the Holly Springs officials sitting a few feet away. “You’ve got to do better, you’ve got to realize you’re holding these people hostage, and it’s not right and it’s not fair… They are being represented by people who do not care about them as long as the bill is paid.”

In determining next steps, Silverpoint Principal Stephanie Vavro told the PSC it may be hard to find someone willing to serve as receiver for the utility department, make significant investments and then hand the keys back to the city. The 2024 bill, Vavro said, doesn’t limit options to a receivership, and alternatives could include condemning the utility or finding a nearby utility to buy the service area.

Answering questions from Central District Public Service Commissioner De’Keither Stamps, Vavro said it’s unclear how much the department is worth, adding an engineer’s study would be needed to come up with a number.

Terry, who reminded the PSC he’s only been Holly Springs’ mayor for just over 60 days, said there’s no way the city can afford the repair costs on its own. The city’s median income is about $47,000, roughly $8,000 less than the state’s as a whole.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post PSC moves toward placing Holly Springs utility into receivership appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

This article presents a factual and balanced account of the situation involving the Holly Springs Utility Department and the Mississippi Public Service Commission. It includes perspectives from various stakeholders, such as city officials, residents, and state commissioners, without showing clear favoritism or ideological slant. The focus is on the practical challenges and financial issues faced by the utility, reflecting a neutral stance aimed at informing readers rather than advocating a particular political viewpoint.

Mississippi Today

Brandon residents want answers, guarantees about data center

Residents of Brandon have raised concerns about the environmental impact and safety of a data center planned for their city.

AVAIO Digital, a Connecticut-based company, announced Aug. 19 that it plans to build a data center in Rankin County. While some celebrated the $6-billion investment and the over $20 million in annual tax revenue it would bring, other residents worry about the data center’s water and power consumption and possible pollution. The 600,000-square-foot facility is expected to be completed by 2027.

‘People genuinely just want answers’

When Nathan Rester first saw the news about the data center, he was immediately concerned. Rester grew up in Brandon and now lives there with his wife and toddler just a few miles from where the data center will be built.

READ MORE: Mississippi Marketplace: Another data center on the way

Rester had followed reports about the air pollution that people in and around Memphis have reported, a result of XAI constructing gas turbines without pollution controls normally used for such turbines. He didn’t want to see what was happening in Memphis happen in Brandon.

His wife, Larkyn Collier, made calls but found the answers unsatisfying.

“ No one could really give a straight answer on how it was being built, what sort of precautions were being taken, whether or not there had been any sort of consideration for utility costs or pollutants or anything like that,” Rester said

In response, Collier and Rester started a petition on change.org that now has over 430 signatures. The petition asks Rankin County leaders to guarantee the data center will not cause such problems. So far they have not received any communication from Rankin or Brandon government officials.

Rester is not completely opposed to the data center being built but he wants the government to guarantee it won’t bring utility bill hikes or pollution.

“ People genuinely just want answers and transparency here. And they want safeguards in place,” Rester said.

The AI boom comes to Mississippi

At their most basic level, data centers store computing equipment. They have been around since the 1940s and power things such as cloud storage. But with the boom in artificial intelligence investment, companies are rapidly constructing data centers across the globe.

The investment bank UBS estimates $375 billion will be spent globally on artificial intelligence in 2025. While this investment has fueled economic and technological growth, data centers have faced skepticism in the communities where they’re built, largely due to the amounts of energy and water they consume and possible pollution they emit.

Mississippi has two large-scale data center projects underway – Compass Datacenters in Meridian and Amazon in Madison County. Including the AVAIO data center, the three will add up to over $26 billion in new capital investment, an unprecedented amount for the state.

Cities and states are embracing data centers because of the potential economic growth, new taxes and innovation they bring.

“This investment is poised to create a lasting, positive impact on the city and the wider region,” Brandon Mayor Butch Lee said in a statement to Mississippi Today. “The project represents a major step forward for Brandon, bringing high-tech jobs and economic growth that will resonate throughout Rankin County and beyond.”

When the property is on the tax rolls and fully up and running, the ad valorem tax will bring in an estimated $23 million in new revenue according to Rankin First, the county’s economic development group. Most of it will go to the local school district.

“ These are not here today. And if we didn’t win this project, we would never see those,” said Garrett Wright, executive director of Rankin First, about tax revenue from the data center.

Rankin First, similar to many economic development groups, is not part of county government and is hired to attract new investment and cultivate existing businesses. It owns the land that the data center will be built on, which has been vacant for around 20 years.

AVAIO is eligible for the state’s data center tax incentive and fee in lieu of property tax. Companies pay a negotiated fee for a set period of time instead of the full property tax. The incentive is designed to encourage economic development. It requires sign off from the county board of supervisors, municipal authorities and Mississippi Development Authority, the state’s economic development agency.

It’s estimated AVAIO will create 60 direct jobs and the Amazon data center 300-400 direct jobs. While data centers create relatively few permanent, direct jobs they create additional jobs in the community. A McKinsey and Company report found that for every direct data center job, approximately 3.5 more jobs are created in the community.

Some residents on social media have wondered whether the data center will negatively impact traffic. Traffic and grade separation of the rail lines have been key conversations as Rankin County has grown. Rankin First acknowledged that AVAIO’s presence will increase traffic but they see it as an opportunity to push for long needed infrastructure improvements.

Rankin First and Brandon have been working with AVAIO for two years and says the company is coming to Brandon, in part, because of the thriving community.

“ The company wants to be a community partner. We see that they’re going to get involved with the local community,” said Regina Todd, assistant director of Rankin First.

Brandon residents want answers

Bailey Henry has lived in Brandon for over a decade. She said that when she read about the new data center on social media, she became concerned.

“ I’ve lived in Mississippi the majority of my life and I was raised to leave things better than you found it,” Henry said. “ And I just don’t think that Mississippi is going to be better off from this.”

Henry is worried about the pressure the data centers will put on the city’s infrastructure, pollution and power demands.

She describes the announcement as “ brief and nonchalant as all the explanations have been. From politicians to people who work for Entergy. It has just been, ‘This is what it is. It’s going to be great. Don’t ask any questions.’”

Henry has made calls to and left voicemails with multiple government offices and has not heard back from any of them.

She’s skeptical, but she hopes she’s wrong.

Brandon concerns echo nationwide conversation

The biggest concerns from residents nationwide over data centers has been potential pollution and increases in utility bills. Across the country, there are stories about data centers driving up energy rates, worsening water shortages, polluting the air and creating a constant noise.

AI data centers demand massive amounts of electricity and run constantly. The average AI data center uses as much electricity as 100,000 households, according to a report from the International Energy Agency.

Another concern is water usage. Data centers need to stay at a specific temperature, and water is one of the most efficient ways to cool the servers. The IEA report found that the average AI data center needs about 528,000 gallons of water every day. For communities that already have water concerns, data centers can exacerbate the problems.

Some communities have blamed the increased demand from data centers for rising electricity bills. While part of these costs may be due to general inflation or paying for infrastructure upgrades, some states are trying to monitor or regulate how households are affected.

A data center’s impact can vary based on the design of the center. But by their very nature they consume a lot of power.

“ AI chips are very power hungry. We’re building a lot of computing capacity, so we need to power all of this,” said Ahmed Saeed, a computer science assistant professor at Georgia Tech.

AVAIO promised “sustainable design,” including rainwater collection and solar panels that would “minimize power demands.” But it’s still unclear what, if any, impact the new data center will have on Rankin County residents.

“ Having clarity on the impact of data centers within the community where they’re building is important,” Saeed said. Saeed believes data centers are here to stay and are key for innovation. But he also thinks there’s a need for more government regulation.

“ They’re not necessarily a negative thing, but on the flip side, in order to make sure that they’re net positive it’s hard to ensure that without some regulation,” Saeed said.

Rankin County’s administrator declined to comment for this story. AVAIO and Brandon Water did not respond to requests for comment.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Brandon residents want answers, guarantees about data center appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a balanced view but leans slightly center-left by emphasizing environmental concerns, community impact, and the need for government transparency and regulation regarding the data center project. It highlights residents’ worries about pollution, utility costs, and infrastructure strain, while also acknowledging economic benefits and job creation. The focus on environmental and social accountability alongside economic development aligns with a center-left perspective that values both growth and sustainability.

Mississippi Today

Democratic DA Scott Colom announces U.S. Senate run against Hyde-Smith

Scott Colom, a Democratic district attorney in north Mississippi, announced today that he will run for the U.S. Senate next year against incumbent Republican Cindy Hyde-Smith.

Colom’s entrance into the race is likely to spark a long and expensive battle for the seat, with both national parties expected to spend millions on the race in the Magnolia State.

Chuck Schumer, the Senate’s Democratic leader from New York, told the New York Times he wants to help elect a Democrat in Mississippi. But the Republican Party is almost certain to defend its ironclad grip on Mississippi, a state where both U.S. Senate seats have been held by the GOP since 1989.

In an interview with Mississippi Today ahead of his announcement, Colom said he intends to cast Hyde-Smith’s voting record as prioritizing “D.C. politics” instead of hard-working Mississippians, including her vote for the “One Big Beautiful Bill” that slashed social safety net programs and provided tax cuts for the wealthy.

“Mississippi needs a senator who’s going to put Mississippi first,” Colom said.

But Colom faces an uphill battle. He’s a Democrat running in Mississippi, with one of the most reliably conservative electorates in the nation.

Mississippi last elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 1982, when it reelected John Stennis. A majority of Mississippians have voted for the Republican nominee for president since 1980.

Still, Colom said he can crack the GOP’s stronghold in the state because he has experience with pitching moderate and progressive solutions to a more conservative electorate, as he did when he defeated long-serving incumbent Forrest Allgood, an independent, for district attorney in 2015.

“At the time, people didn’t think I could win the DA’s race,” Colom said.

A native of Columbus, Colom is the elected district attorney of the 16th Circuit Court District, which includes Lowndes, Oktibbeha, Clay and Noxubee counties. He is the first Black DA for the district.

He first won that election by casting his opponent as an incredibly harsh prosecutor who was more concerned with obtaining stiff sentences for convicted criminals than true rehabilitation. After Colom took office, he said he focused his office’s efforts on tackling violent crime and promoting alternative sentencing for nonviolent offenders.

“I have faith that the truth always sees through if you get the message out, speak with conviction and lead with your values,” Colom said. “That’s my plan. I want to speak with my values.”

For example, Colom said he would push for legislation that raises the nation’s minimum wage and exempts law enforcement officers and public school teachers from paying federal income taxes.

This may be the first time the two have competed head-to-head, but it will not be the first time Colom and Hyde-Smith have butted heads. Former President Joe Biden in 2023 nominated Colom to a vacant federal judicial seat in northern Mississippi, but Hyde-Smith thwarted the nomination.

Despite support for Colom from Roger Wicker, Mississippi’s senior U.S. senator, Hyde-Smith was able to block his nomination because of a longstanding tradition in the U.S. Senate that requires senators from a nominee’s home state to submit “blue slips” if they approve of the candidate.

Hyde-Smith never returned one of these slips for Colom. If both senators don’t submit a blue slip, the nominee typically does not advance to a confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Hyde-Smith, at her reelection launch last week, mentioned her opposition to Colom’s elevation to the federal bench.

“He thought he was going to be a federal judge, and I blocked him,” Hyde-Smith said to applause.

Colom is the first Democrat to announce his candidacy for the Senate seat. Ty Pinkins, an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for U.S. Senate in 2024, has declared he’s also running for the Senate again in 2026 as an independent.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Democratic DA Scott Colom announces U.S. Senate run against Hyde-Smith appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The article presents a factual overview of Democratic candidate Scott Colom’s Senate run against Republican Cindy Hyde-Smith, highlighting Colom’s progressive policy positions such as raising the minimum wage and critiquing Hyde-Smith’s voting record on social safety net cuts. While it includes perspectives from both sides and contextualizes Mississippi’s conservative political landscape, the emphasis on Colom’s values and policy proposals, along with critical framing of Hyde-Smith’s record, suggests a slight lean toward a center-left viewpoint. The tone remains largely informative without overt partisan language.

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

DEI, campus culture wars spark early battle between likely GOP rivals for governor in Mississippi

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days ago

‘They broke us down’: New Orleans teachers, fired after Katrina, reflect on lives upended

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Alabama state grocery tax to fall 1% on Monday

-

Mississippi Today4 days ago

Trump proposed getting rid of FEMA, but his review council seems focused on reforming the agency

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed5 days ago

Missouri joins dozens of states in eliminating ‘luxury’ tax on diapers, period products

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed4 days ago

Tennessee ranks near the top for ICE arrests

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Warm and Mainly Dry Labor Day

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

NC Labor Day 2025: A state that’s best for business is also ranked worst for workers