Mississippi Today

Rankin sheriff says he learned at the knee of a former Simpson County sheriff, Lloyd ‘Goon’ Jones

The law enforcement official that Rankin County Sheriff Bryan Bailey regards as his mentor had a reputation for terrorizing Mississippi’s Black community.

His name? Lloyd Jones.

“Of all the law enforcement officers I have ever questioned, he was the most detestable,” said Constance Slaughter-Harvey, who served as an assistant secretary of state for Mississippi. As proof, she pointed to his 1970 deposition, where he repeatedly said “n—–” and then defended his use of the racist slur.

Now Sheriff Bailey is under Justice Department scrutiny for his office’s “Goon Squad,” which terrorized two Black men, hurled racial slurs at them, used a sex toy on them and shot one of them in the mouth.

On Nov. 30, The New York Times and the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting at Mississippi Today revealed a disturbing pattern of violence by Rankin County deputies stretching back two decades. Reporters reviewed dozens of allegations and corroborated 17 incidents involving 22 victims based on witness interviews, medical records, photographs of injuries and other documents.

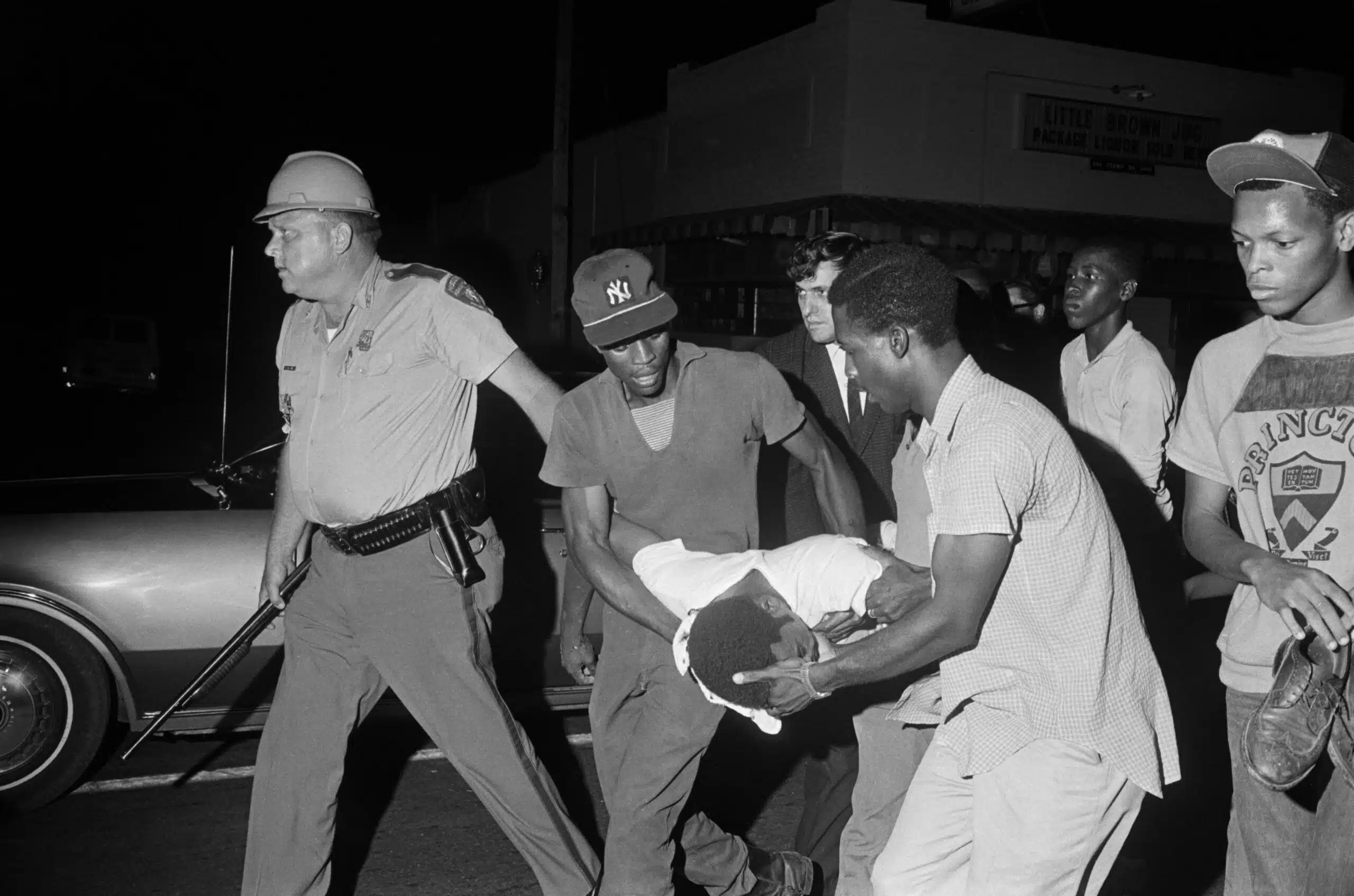

The brutality harkened to the Jim Crow days when some law enforcement officers carried out violence in the name of preserving the Southern “way of life.”

Between 1956 and 1975, Lloyd Jones worked as an inspector at the Mississippi Highway Patrol. Civil rights leaders gave him the nickname “Goon,” and the nickname stuck.

The Justice Department concluded that Jones killed Ben Brown in 1967. Brown, who had been involved in the civil rights movement, happened to walk past a standoff between law enforcement officers and protesters near the Jackson State University campus.

The FBI quoted Jones as telling a coworker that he killed “the n—–” with his 12-gauge shotgun, took it home, cleaned it, wrapped it in a blanket and hid it in his attic. He admitted in a sworn statement that he fired his shotgun 10 or 15 times that night.

Three years later, Jones was over state troopers who, along with Jackson police, responded to a protest on the Jackson State University campus. Law enforcement officers fired more than 400 rounds of ammunition in less than 30 seconds in every direction, many of them into a women’s dormitory.

Jones declared under oath that a sniper had fired at troopers before they unleashed their barrage of bullets, but journalists and some Jackson police officers testified they witnessed no such sniper fire.

By the time the gunfire ended, two young men were dead: Phillip Gibbs, a political science major who was married with two children, and James Green, a Jim Hill High School senior who was walking home from work. A dozen others were struck by bullets but survived.

When the Rev. John Perkins led activists on a Feb. 7, 1970, civil rights march in Simpson County, Jones had 14 troopers watching their every move, according to court documents.

Fellow activist Doug Huemmer was arrested on a charge of reckless driving. He said a trooper had already told him that if he didn’t leave Simpson County, “he would kill me.”

Troopers hauled Huemmer and other activists to the Rankin County Jail. When Perkins heard the news, he headed that way.

After arriving at the jail, Perkins and Huemmer said they and other activists were brutalized by then-Rankin County Sheriff Jonathan Edwards and other law enforcement officers. (An appeals court judge had already concluded that Edwards and his deputies beat Black Mississippians who attempted to vote.)

Huemmer said that, after one officer whacked him four times with a blackjack, he “saw stars” and fell to the floor.

While being held in a different room, Perkins said Jones kicked him and told him, “We could have killed you a long time ago.”

He said he balled up to protect himself from blows to his head and groin. One officer shoved a fork up his nose.

Perkins said another officer jammed a pistol against his head, and he thought he was going to die. The gun clicked.

The harassment didn’t stop after their release. Six months later, Huemmer was jailed in Rankin County again, this time after making a U-turn. He said the judge was going to let him go — until the judge found out he had been involved in the Mendenhall protest and ordered him put behind bars.

Huemmer said he and Perkins became victims, not just of “a racist paradigm,” but of the authority given to Southern sheriffs following the Civil War. “Sheriffs filled a power vacuum,” he said, “but the system rotted and became corrupt.”

In 1976, Jones became sheriff in Simpson County, where the Perkins’ family lived. A sense of fear and terror pervaded the Black community, said Perkins’ son, Derek. “People were afraid. They knew he could go inside their house and arrest them. I’ve seen that done.”

The FBI quoted Jones as saying, “Those n—–s don’t mess with me in Simpson County because they know I will put them in their place.”

Mary White, who served for decades as secretary for the Simpson County NAACP branch, described that time as “rough on Black people.”

The NAACP collected allegations of the beatings of Black Mississippians or of having drugs and guns tossed inside their cars, she said. “We got calls on a lot of different cases.”

Perkins’ daughter, Priscilla, recalled Jones entering their Simpson County home with two other white men just as dawn was breaking. Not knowing what else to do, she pretended to sleep.

News of a new “Goon Squad” has resurrected nightmares for the Perkins family.

“The Goon Squad was eerily similar to 53 years ago when Rankin County officers tortured my father and beat him in the Rankin County Jail in February 1970,” said Perkins’ daughter, Elizabeth. “The spirit of ‘Goon’ Jones lives on through the Goon Squad. We’ve got to break this Rankin County Goon Squad cycle.”

In the early 1990s, Bailey got his first job under Jones, who had survived a shooting a few years earlier. Deputy James Barnett was killed in the incident. In 1995, Jones became a murder victim.

After the slaying, Bailey appeared on television to praise his boss. “He worked seven days a week, 12 and 14 hours a day, and he wouldn’t ask us to do anything he wouldn’t do hisself [sic],” he said. “It’s an honor for me to work with him.”

Twenty years later, Bailey posted on Facebook that Jones was his mentor and wrote: “You had such an influence on my life and my career in law enforcement … you are no doubt a part of who I am and what I am today. I loved you like a father and I still miss you so much. I remember and use everything you taught me to this day.”

Slaughter-Harvey worked as one of the lawyers who brought the litigation against Jones. She still remembers the lawman glaring at her when she questioned him in Rev. Perkins’ lawsuit.

“He looked like he could kill me,” she said. “John Perkins forgave him, which is more than I can do. I can try to forgive him, but I can’t forget.”

In 2014 and 2015, a series of police pursuits of suspects from Rankin and other surrounding counties into the capital city made headlines after some car crashes led to injuries and deaths. Jackson Police Chief Lee Vance told the Clarion Ledger that “chasing people down busy streets during a busy time of day, pursuing misdemeanor suspects is something I don’t agree with.”

Jackson City Councilman Kenny Stokes drew national attention when he suggested that rocks, bricks and bottles be thrown at officers who chase misdemeanor suspects into Jackson.

Sheriff Bailey responded angrily that Rankin County citizens elected him “to keep them safe. That’s what we’re going to continue to do.”

He told Therese Apel, now CEO of Darkhorse Press, “The day’s not going to come where people think they can commit a crime in Rankin County and race back to Jackson …. We’re coming after ‘em. They started this. We didn’t. They came over here and committed a crime.”

He told Stokes to “keep those thugs over in the ward with him. … In my opinion, Kenny Stokes represents everything that is wrong with the city of Jackson and why it’s going downhill. … He says this is racism. Yes, it is racism — racism against every officer, against every deputy who bleeds blue. Just makes me sick for him to incite hatred and violence against the officers.”

Stokes is “standing behind his city limits in Jackson and talking all his big talk,” Bailey said. “I challenge him to cross this river, and I’ll drive my car over there and let him throw a rock at me. I’ll have him picking up trash on the side of the road for the next few years.”

He said if any Rankin County officer “gets hurt over there, we’re going to do our best to take everything he has — his state retirement, his paycheck and everything else.”

On Feb. 7, 2017, Bailey joined one of those chases after carjacking suspects and fired his gun into a fleeing vehicle. The bullet went through the rear passenger door and hit a teenager.

Former deputies say Sheriff Bailey remained obsessed with Braxton, a village of less than 200 where Jones once lived. Part of the community is in Rankin County and part of it is in Simpson County. Bailey grew up in the nearby village of Puckett, where he graduated high school in 1985.

Deputies had responded to a series of calls at 135 Conerly Road in Braxton involving aggravated assault, drug sales and a drug-related murder. That is the house where the Goon Squad later tortured the two Black men.

Brett McAlpin, chief investigator for the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department under Bailey, lived just a mile from that house. He had been involved in the investigation of the drug-related murder at that same house.

The charges that McAlpin and other officers have pleaded guilty to detailed what they did on Jan. 24 at that house.

That evening, a white neighbor told him several “suspicious” Black men had been staying at that four-bedroom home, which was owned by a white woman.

McAlpin asked Investigator Christian Dedmon to take care of it, and Dedmon reached out to a shift of officers known as “The Goon Squad,” because of “their willingness to use excessive force and not to report it,” according to the charges.

At 9:28 p.m. Dedmon texted three members of the Goon Squad, “Are y’all available for a mission?”

Because there was a chance of cameras, he told them to “work easy,” rather than kick the door down. Deputy Hunter Elward responded with an eyeroll emoji. Deputy Daniel Opdyke texted back an image of a crying baby.

Dedmon texted the group, “No bad mugshots,” greenlighting excessive force on the body that wouldn’t be captured in a photo.

After kicking in the carport door, they entered the house. They had no warrant.

Tasers are designed to incapacitate a suspect by transmitting a 50,000-volt electric shock. Deputies used them instead to torture Michael Jenkins and Eddie Parker after handcuffing them.

When Dedmon demanded that Parker tell him where the drugs were, Parker replied there were no drugs. Dedmon took out his gun and fired it into the wall.

Dedmon again demanded to know where the drugs were. Parker responded again that there were no drugs.

Deputies hurled racial slurs at the Black men, accused them of having sex with the white woman and told them to stay out of Rankin County and go back to majority-black Jackson.

When Opdyke found a dildo, he forced it into the mouth of Parker. But before he could do the same to Jenkins, Dedmon grabbed it and slapped the two Black men in the face with it and taunted them.

Dedmon also threatened to anally rape the men with the dildo, but stopped when he discovered Jenkins had defecated on himself.

Elward put his gun into Parker’s mouth and pulled the trigger. The unloaded gun clicked.

Elward racked the gun again, but when he pulled the trigger this time, the gun fired. The bullet lacerated Jenkins’ tongue and broke his jaw before exiting his face.

As Jenkins lay bleeding, officers huddled on the porch to devise a false story to cover up their crimes. They planted a gun next to Jenkins, claiming Elward shot Jenkins in self-defense.

McAlpin told Parker that if he stuck to the false story, he would be released from jail.

Richland narcotics investigator Joshua Hartfield threw the men’s soiled clothes into the woods behind the house. He also removed the hard drive from the home’s surveillance system and threw it into a creek in Florence.

Dedmon took meth that had yet to be entered into evidence and submitted it to the State Crime Lab as belonging to Parker.

McAlpin and Middleton told officers that if any of them revealed what happened, they would “kill them,” according to the charges.

Sentencing hearings for the five former deputies and the former Richland police officer are set for Jan. 18 and 19 in the U.S. District Court in Jackson.

After these guilty pleas, Sheriff Bailey denied he knew anything about the Goon Squad.

But he did know the background of the Goon Squad leader, Lt. Middleton, who pleaded guilty to culpable-negligence manslaughter for speeding at 98 mph in his patrol car without sirens or flashing lights before colliding with Desmonde Harris in 2005. A Hinds County judge awarded Harris’ family $500,000.

Sheriff Bailey also knew about McAlpin, whom several former deputies described as a “bully” known to “rough up” suspects. The Times and Mississippi Today interviewed more than 50 people who say they witnessed or experienced torture at the hands of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department. The investigation found McAlpin was involved in at least 13 of the arrests and was repeatedly described by witnesses as leading the raids.

McAlpin was named in at least four lawsuits and six complaints going back to 2010, but that didn’t stop the sheriff from naming him “Investigator of the Year.”

Christian Dedmon shot up the ranks of the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department to become a narcotics investigator, despite his family background. His first cousin, Deryl Dedmon, is still serving 50 years in federal prison for a hate crime that ended with the beating and killing of a Black man, James C. Anderson, in 2011.

Deryl Dedmon was part of a group of 10 young people, all white, from Rankin County who conducted raids into Jackson, which they called “Jafrica.”

The FBI investigation showed that the raids into the capital city started with the beating of homeless men. When this white mob stumbled upon a Black man at a service station, they beat him mercilessly. One Black man at a golf course begged for his life.

“Like a lynching, for these young folk going out to ‘Jafrica’ was like a carnival outing,” said Carlton Reeves, the second Black federal judge in Mississippi history. “It was funny to them — an excursion which culminated in the death of innocent, African-American James Craig Anderson. On June 26, 2011, the fun ended.”

In sentencing Deryl Dedmon, Carlton Reeves described those raids: “ A toxic mix of alcohol, foolishness and unadulterated hatred caused these young people to resurrect the nightmarish specter of lynchings and lynch mobs from the Mississippi we long to forget.

“Like the marauders of ages past, these young folk conspired, planned, and coordinated a plan of attack on certain neighborhoods in the City of Jackson for the sole purpose of harassing, terrorizing, physically assaulting and causing bodily injury to black folk. They punched and kicked them about their bodies — their heads, their faces. They prowled. They came ready to hurt. They used dangerous weapons; they targeted the weak; they recruited and encouraged others to join in the coordinated chaos; and they boasted about their shameful activity. This was a 2011 version of the N—– hunts.”

The judge wondered aloud, “How could hate, fear or whatever it was that transformed genteel, God-fearing, God-loving Mississippians into mindless murderers and sadistic torturers?”

He had no answer.

Bailey worked in Simpson County alongside Paul Mullins, and the two teamed up again in Rankin County.

Mullins worked for 21 years in the Rankin County Sheriff’s Department under several different sheriffs.

After Bailey became sheriff in 2012, Mullins served as lieutenant over the late shift. The sheriff never asked him to do anything wrong or illegal, he said. “He let me run my shift.”

While working there, he never participated in any violence or witnessed any, he said. “My dad always told me to ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’”

Mullins said the first time he ever heard anything about the Goon Squad was in August when Rankin County deputies pleaded guilty to charges. He called what happened “a black eye for everybody in Rankin County.”

In 2022, the late shift created challenge coins that read “Rankin County Sheriff’s Department” on one side and “Goon Squad” on the other, featuring a drawing of mobsters.

A deputy, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, told Mississippi Today that Lt. Jeffrey Middleton, the lieutenant over the Goon Squad, ordered about 50 challenge coins.

“What they did set back law enforcement another 25 years,” the deputy said.

After Mullins was elected sheriff of Simpson County in 2019, Rankin County, at Bailey’s request, gave Mullins an unmarked 2019 Chevy Tahoe, a winch and a winch bumper, plus a Motorola mobile radio and a Motorola portable radio, according to the Dec. 26, 2019, minutes of the Rankin County Board of Supervisors.

Mullins also received a 9mm Glock, an AR-15 with a red dot scope, a Nikon Black Rangex 4K Laser Rangefinder and a Stihl chainsaw.

The cost to taxpayers? At least $75,000, according to prices for those items.

The justification for giving away these items: they were “surplus.”

Five days after Christmas in 2019, Clint Pennington slashed a nearly 7-inch gash in the back of his then-wife, Amanda, before cutting his own throat. (Pennington is the son of former Rankin County Sheriff Ronnie Pennington and the brother of Kristi Pennington Shanks, Sheriff Bailey’s girlfriend, who also serves as his administrative assistant.)

In 2022, Clint Pennington pleaded guilty to aggravated domestic violence, and the judge sentenced him to five years in prison. He is slated to be released in less than 18 months. Under Mississippi law, he could have received a sentence of up to 30 years.

Rather than being locked up in state prison, however, he is spending his days at the Simpson County Jail.

Mullins said he originally kept Pennington because “his daddy used to be sheriff and his wife was working at the Rankin County jail.”

Pennington hasn’t had any infractions since coming to the Simpson County Jail, Mullins said. “He works on the road crew.”

He said the Mississippi Department of Corrections asked him to house Pennington after his sentencing, presumably for safety reasons.

“Some people in the public think I’m doing it for Bryant Bailey,” he said, “but I would do it for anybody.”

Sheriff Bailey now faces his toughest challenge as sheriff: a federal investigation into his office.

At an Aug. 3 press conference following the officers’ guilty pleas to torturing Jenkins and Parker, the sheriff talked about how the crimes had hurt him. “I have 115 other deputies trying to keep this a safe county, trying to build a good reputation,” he said, “and they have robbed me of all of this.”

He shifted the blame to the officers. “My moral boundary is set by my Christian faith,” he said. “Do I cross that boundary? Sometimes I do. These guys were so far past any boundary that I know of. It’s unbelievable what they did. This is a bunch of criminals that did a home invasion.”

He acknowledged that he knew his deputies well. Asked how he didn’t know about them beating and torturing these two Black men, he replied, “The complaint has to come in. The reports have to come in. Something has to come in that I’ve been notified. That’s what I’ve got supervisors for.”

Under the sheriff’s system at the time, all complaints went to the supervisors. Two of those were McAlpin and Middleton, who have each pleaded guilty to federal charges in the Goon Squad’s activities.

Seven people told reporters they had mailed letters, filed formal complaints or called the sheriff personally to tell him about the abuse they experienced. One, a deputy of a neighboring county at the time, said the sheriff hung up on him.

Bailey disputed that he tolerates violence, saying, “If somebody comes back there [to jail] with a black eye, there better be an explanation.”

But the Times and Mississippi Today found at least seven jail mugshots that show injured people, including then-Hinds County Deputy Rick Loveday, who said jailers correctly guessed that McAlpin had beaten him up.

“How would they know,” Loveday asked, “unless a lot of people walked in looking like me?”

Bailey told reporters the only thing he’s guilty of is “trusting grown men that swore an oath to do their job correctly. I’m guilty of that.”

Informed that several high-ranking deputies were involved in arrests that had sparked accusations of brutal treatment, the sheriff replied, “I have 240 employees, there’s no way I can be with them each and every day.”

Former Mississippi Corrections Commissioner Robert L. Johnson, who previously served as police chief for the city of Jackson, called the sheriff’s response “a piss-poor excuse. You just can’t have that kind of activity and not be aware of it.”

Over the past two decades, nearly a dozen lawsuits have accused Rankin County deputies of brutality. Bailey, however, said he had no idea any such violence was taking place.

Johnson said he made sure he read every lawsuit filed against the Mississippi Department of Corrections so that he could know “what the hell is going on, and I was supervising 4,000 people instead of 240.”

Brian Howey, Nate Rosenfield and Ilyssa Daly contributed to this report. This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University and supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Judge: Felony disenfranchisement a factor in ruling on Mississippi Supreme Court districts

The large number of Mississippians with voting rights stripped for life because they committed a disenfranchising felony was a significant factor in a federal judge determining that current state Supreme Court districts dilute Black voting strength.

U.S. District Judge Sharion Aycock, who was appointed to the federal bench by George W. Bush, last week ruled that Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts violate the federal Voting Rights Act and that the state cannot use the same maps in future elections.

Mississippi law establishes three Supreme Court districts, commonly referred to as the northern, central and southern districts. Voters elect three judges from each to the nine-member court. These districts have not been redrawn since 1987.

READ MORE: Mississippians ask U.S. Supreme court to strike state’s Jim Crow-era felony voting ban

The main district at issue in the case is the central district, which comprises many parts of the majority-Black Delta and the majority-Black Jackson Metro Area.

Several civil rights legal organizations filed a lawsuit on behalf of Black citizens, candidates, and elected officials, arguing that the central district does not provide Black voters with a realistic chance to elect a candidate of their choice.

The state defended the districts arguing the map allows a fair chance for Black candidates. Aycock sided with the plaintiffs and is allowing the Legislature to redraw the districts.

The attorney general’s office could appeal the ruling to the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. A spokesperson for the office stated that the office is reviewing Aycock’s decision, but did not confirm whether the office plans to appeal.

In her ruling, Aycock cited the testimony of William Cooper, the plaintiff’s demographic and redistricting expert, who estimated that 56,000 felons were unable to vote statewide based on a review of court records from 1994 to 2017. He estimated 60% of those were determined to be Black Mississippians.

Cooper testified that the high number of people who were disenfranchised contributed to the Black voting age population falling below 50% in the central district.

Attorneys from Attorney General Lynn Fitch’s office defended the state. They disputed Cooper’s calculations, but Aycock rejected their arguments.

The AG’s office also said Aycock should not put much weight on the number of disenfranchised people because the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals previously ruled that Mississippi’s disenfranchisement system doesn’t violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Aycock, however, distinguished between the appellate court’s ruling that the system did not have racial discriminatory intent and the current issue of the practice having a racially discriminatory impact.

“Notably, though, that decision addressed only whether there was discriminatory intent as required to prove an Equal Protection claim,” Aycock wrote. “The Fifth Circuit did not conclude that Mississippi’s felon disenfranchisement laws have no racially disparate impact.”

Mississippi has one of the harshest disenfranchisement systems in the nation and a convoluted method for restoring voting rights to people.

Other than receiving a pardon from the governor, the only way for someone to regain their voting rights is if two-thirds of legislators from both chambers at the Capitol, the highest threshold in the Legislature, agree to restore their suffrage.

Lawmakers only consider about a dozen or so suffrage restoration bills during the session, and they’re typically among the last items lawmakers take up before they adjourn for the year.

Under the Mississippi Constitution, people convicted of a list of 10 types of felonies lose their voting rights for life. Opinions from the Mississippi Attorney General’s Office have since expanded the list of specific disenfranchising felonies to 23.

The practice of stripping voting rights away from people for life is a holdover from the Jim Crow era. The framers of the 1890 Mississippi Constitution believed Black people were most likely to commit certain crimes.

Leaders in the state House have attempted to overhaul the system, but none have gained any significant traction in both chambers at the Capitol.

Last year, House Constitution Chairman Price Wallace, a Republican from Mendenhall, advocated a constitutional amendment that would have removed nonviolent offenses from the list of disenfranchising felonies, but he never brought it up for a vote in the House.

Wallace and House Elections Chairman Noah Sanford, a Republican from Collins, are leading a study committee on Sept. 11 to explore reforms to the felony suffrage system and other voting legislation.

Wallace previously said on an episode of Mississippi Today’s “The Other Side” podcast that he believes the state should tackle the issue because one of his core values, part of his upbringing, is giving people a second chance, especially once they’ve made up for a mistake.

“This issue is not a Republican or Democratic issue,” Wallace said. “It allows a woman or a man, whatever the case may be, the opportunity to have their voice heard in their local elections. Like I said, they’re out there working. They’re paying taxes just like you and me. And yet they can’t have a decision in who represents them in their local government.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Judge: Felony disenfranchisement a factor in ruling on Mississippi Supreme Court districts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a focus on voting rights and racial justice issues, highlighting the impact of felony disenfranchisement on Black voters in Mississippi. It emphasizes civil rights concerns and critiques longstanding policies rooted in the Jim Crow era, which aligns with center-left perspectives advocating for expanded voting access and systemic reform. The coverage is factual and includes viewpoints from multiple sides, but the framing and emphasis on racial disparities and voting rights restoration suggest a center-left leaning.

Mississippi Today

Jackson police chief steps down to take another job, national search to come

Jackson Police Department Chief Joseph Wade told the mayor last week he was choosing to retire after 29 years of service and two years at the helm of the force. Wade said he’d been given another job opportunity, which has yet to be announced.

His last day is Sept. 5.

Mayor John Horhn said he told Wade the officer would be crazy not to take the job — one that comes with less stress and more pay.

“His wife has been on his back, his blood pressure has been up,” Horhn said during Tuesday’s City Council meeting. “He has done a commendable job.”

Wade became chief during a period in which Jackson was called the murder capital of America. Under his tenure, Wade said crime has fallen markedly, including a roughly 45% reduction in homicides so far this year compared to the same period in 2024, the Clarion Ledger reported. He said he’s also increased JPD’s force by 37, for a total of 258 officers.

Wade said his biggest accomplishment is reestablishing trust. “We are no longer the laughing stock of the law enforcement community,” he said.

The chief’s departure comes less than two months after Horhn took office, replacing former Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba who originally appointed Wade, and on the heels of a spate of shootings that Wade said were driven by gangs of young men.

“I have received so many calls from the community: ‘Chief, please don’t leave us,'” Wade told the crowd in council chambers.

But Wade said he “would rather leave prematurely than overstay my welcome,” adding that the average tenure of a police chief is 2.5 years.

Wade said that last year he stood next to Jackson Councilman Kenny Stokes and told the media he was going to cut crime in half, “And what did I do? Cut it in half,” he said.

“What I’ve seen in our community in some situations is people want police, but they don’t want to be policed,” Wade said.

Hinds County Sheriff Tyree Jones will serve as interim police chief until the administration finds a replacement. Jones said he has not finalized a contract with the city, responding to a question about whether he will draw a salary from both agencies.

“I could think of no one better than the sheriff of Hinds County,” Horhn said, adding that the appointment is temporary.

Jones said during the meeting that his responsibility as sheriff will continue uninterrupted and that his goal within JPD is to ensure continued professionalism in the department.

“I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my dear friend and retired police chief Joe Wade,” Jones said. “Again, let me be clear, I have no aspirations to permanently hold the position.”

Horhn said there is precedence for the dual role that “Chief Sheriff Jones is about to embark upon,” citing former mayor Frank Melton’s hiring of Sheriff Malcolm McMillin.

The city has enlisted help from former U.S. Marshal George White and the former chief of the Mississippi Highway Patrol, Col. Charles Haynes, to lead the Law Enforcement Task Force that will conduct a nationwide search to fill the position. The administration expects that to take between 30 and 60 days, according to a city press release.

The release said the task force will also examine safety challenges in Jackson more broadly, such as youth crime, drug crimes, departmental needs and interagency coordination.

“I am grateful that Marshal White and Col. Haynes have agreed to lead this important effort. Their breadth of experience, commitment to public safety and deep understanding of law enforcement challenges will ensure the task force conducts a rigorous search for our next chief,” said Horhn. “I am confident they will help shape solutions that address the evolving needs of Jackson.”

The city said it would soon release details about the opportunity for the public to offer input on the process.

“Hinds County is all in for whatever we have to do to make Jackson and Hinds County the safest it can be,” Hinds County Supervisors President Robert Graham said during the meeting.

Wade, who hails from nearby Terry, graduated from JPD’s 23rd recruit class in 1995, rising from a police recruit and hitting every rung of the ladder on his way to chief. “I was homegrown,” he said.

Wade said he received “an amazing offer in a private sector at an amazing organization. Don’t ask me where. That will be released at the appropriate time.”

This story may be updated.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Jackson police chief steps down to take another job, national search to come appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a straightforward news report on the resignation of a police chief, focusing on facts, quotes from officials, and crime statistics without evident ideological framing. It covers perspectives from multiple local government figures and avoids partisan language, reflecting a neutral, balanced tone typical of centrist reporting.

Mississippi Today

Bluesky blocks access in Mississippi, citing free speech and privacy concerns over state law

Mississippians can no longer access the Bluesky app after the social media platform blocked access to users in the state.

Bluesky said on Friday that it made the decision after the U.S. Supreme Court declined for now to block a Mississippi state law that the platform said limits free expression, invades people’s privacy and unfairly targets smaller social media companies. The state law, passed in 2024, requires users of websites and other digital services to verify their age.

“The Supreme Court’s recent decision leaves us facing a hard reality: comply with Mississippi’s age assurance law—and make every Mississippi Bluesky user hand over sensitive personal information and undergo age checks to access the site—or risk massive fines,” the company wrote in a statement. “The law would also require us to identify and track which users are children, unlike our approach in other regions. We think this law creates challenges that go beyond its child safety goals, and creates significant barriers that limit free speech and disproportionately harm smaller platforms and emerging technologies.”

Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch, whose office defended the law, told the justices that age verification could help protect young people from “sexual abuse, trafficking, physical violence, sextortion and more,” activities that the First Amendment does not protect.

The age verification law added Mississippi to a list of Republican-led states where similar legal challenges are playing out.

NetChoice is challenging laws passed in Mississippi and other states that require social media users to verify their ages, and asked the Supreme Court to keep the measure on hold while a lawsuit plays out.

That came after a federal judge prevented the 2024 law from taking effect. But a three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in July that the law could be enforced while the lawsuit proceeds.

On Aug. 14, the Supreme Court rejected an emergency appeal from a tech industry group representing major platforms such as Facebook, X and YouTube.

There were no noted dissents from the brief, unsigned order. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote that there’s a good chance NetChoice will eventually succeed in showing that the law is unconstitutional, but hadn’t shown it must be blocked while the lawsuit unfolds.

Bluesky grew after the 2024 presidential election. Many users of X, which is owned by Elon Musk, retreated from the platform in response to the billionaire’s strong support of Donald Trump.

In Bluesky’s statement explaining its decision to block access in Mississippi, the company said age verification systems “require substantial infrastructure and developer time investments, complex privacy protections, and ongoing compliance monitoring — costs that can easily overwhelm smaller providers.”

“This dynamic entrenches existing big tech platforms while stifling the innovation and competition that benefits users,” the company added.

Bluesky said it did follow other digital safety regulations, such as the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act. Under that statute, age checks are required only for accessing certain content and features, and Bluesky does not track which users are under 18, the platform said:

“Mississippi’s law, by contrast, would block everyone from accessing the site—teens and adults—unless they hand over sensitive information, and once they do, the law in Mississippi requires Bluesky to keep track of which users are children.”

The Mississippi law, authored by Rep. Jill Ford, a Republican from Madison, is called the “Walker Montgomery Protecting Children Online Act,” named after a Mississippi teen who reportedly committed suicide after an overseas online predator threatened to blackmail him.

The Associated Press contributed to this report

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Bluesky blocks access in Mississippi, citing free speech and privacy concerns over state law appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content presents a perspective that emphasizes concerns about free speech, privacy, and the impact of government regulation on smaller tech companies, which aligns with a more progressive or liberal viewpoint on digital rights and corporate regulation. It critiques a Republican-led state law as potentially overreaching and harmful to innovation, while also acknowledging the law’s intent to protect children. The balanced presentation of both sides, with a slight emphasis on the tech platform’s viewpoint and civil liberties, suggests a center-left bias.

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

New I-55 bridge between Arkansas, Tennessee named after region’s three ‘Kings’

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

DEA agents uncover 'torture chamber,' buried drugs and bones at Kentucky home

-

News from the South - Virginia News Feed7 days ago

Erin: Tropical storm force winds 600 miles wide eases into Atlantic | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed6 days ago

Missouri settles lawsuit over prison isolation policies for people with HIV

-

The Center Square6 days ago

Georgia ICE arrests up 367 percent from 2021, making for ‘safer streets, open jobs | Georgia

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

Texas House passes Hill Country relief effort | Texas

-

Local News6 days ago

Florida must stop expanding ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ immigration center, judge says

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Quintissa Peake, ‘sickle cell warrior’ and champion for blood donation, dies at 44