Mississippi Today

Q&A: Rev. Charlton Johnson on seeing Medicaid expansion not as a financial issue, but a moral necessity

Rev. Charlton Johnson only joined Together for Hope as leader of its Delta region in September, but he began thinking about Medicaid expansion long before that.

Together for Hope, an organization that works with people in the poorest counties in the country, has ramped up its efforts advocating for Medicaid expansion in Mississippi. The nonprofit hosts summits all over the states to bring together faith leaders, medical experts and health care advocates to raise awareness about Medicaid expansion. The policy, which would provide health insurance for an additional 200,000 to 300,000 Mississippians, would greatly improve health care access for the communities they work with, according to the organization.

But Gov. Tate Reeves remains steadfast in his opposition, despite support from a majority of Mississippians, and has derisively referred to Medicaid expansion as adding more people to “welfare rolls.”

Mississippi is one of only 10 states that has not expanded Medicaid. Over its first few years of implementation, research shows expansion would bring in billions of dollars to Mississippi and help the state’s struggling hospitals.

Johnson, who was born in Greenville and who has worked as a chaplain for hospitals in Memphis and Jackson, acknowledges its financial benefits. But expansion is about more than that, according to Johnson — it’s really about helping your neighbor.

Johnson spoke with Mississippi Today about the need for Medicaid expansion, and what the Governor’s refusal to consider the policy says about morality in Mississippi.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Mississippi Today: Talk to me a little bit about what Together for Hope is and what it does for people who have not heard of it.

Rev. Charlton Johnson: It is a coalition with its focus on fighting rural, persistent poverty. Persistent poverty is defined as an area that has been under the federal threshold for poverty for consistently 30 years, and in Mississippi alone, we have 53 counties that meet that definition of persistent poverty. We are a national group, so I’m serving what we call the Delta region, which comprises the poorest counties in Mississippi, in Arkansas and Missouri; some parishes in Louisiana; Illinois — basically along the Mississippi River.

MT: Can you explain a little more in detail what the organization does, specifically?

Johnson: We serve as a bridge for grassroots organizations and what we call grass-top organizations that are trying to find ways to make an impact on the ground. For instance, there is this group that we partner with out of the Delta called Hands for Hope. They have tried to intervene with the food scarcity in that area because they don’t have a lot of grocery stores and fresh foods. Most people do their grocery shopping at Family Dollar or Dollar General. Now, they have a space where they receive fresh foods, like a distribution. Our job is making that connection between the community and that organization. A lot of grassroots organizations have a mission or idea of how they want to help the community, but they don’t always have the resources to turn something around.

MT: What kind of work does Together for Hope do around Medicaid expansion?

Johnson: It’s largely advocacy, with hosting the summit. Expansion has not been framed the right way. That was even mentioned in our last staff meeting, that we almost need to just pull it back from saying Medicaid expansion versus just starting to meet those who are in the gap. There are so many people who are in that void of not being able to receive health care.

As a chaplain in hospitals, I’ve seen people use the emergency room as their primary care physicians, or they can’t go to the doctor and get sick enough they end up in the ER. That’s because people don’t have insurance. Seeing that was an awakening moment for me — it was when I began to recognize that people are not just running in here because they’re sick. It’s because the hospital has become their only option.

MT: I’m sure you were hearing about expansion long before starting this job. How do you think we have been talking about expansion, and how do you think we should be talking about it?

Johnson: Before coming into this role, I heard conversations about the need to expand Medicaid, which came while President Obama was in office. But there was so much resistance from red states to support that kind of initiative. People were trying to do their best to tear it apart. And Mississippi, of course, being the red state that it has long been, did not accept monies to help make this program more robust in Mississippi. So to hear Governor Reeves saying that he still isn’t interested in expanding Medicaid, to me it is just continuing the talking point that I heard from people who share his political ideology. When I heard that this organization Together for Hope was out there trying to help people better understand how it helps, not just people but the community as a whole and to also fight poverty, I wanted to be on the front lines.

MT: I’m wondering how you, as a pastor, square red states that are really religious with this resistance to helping some of the most vulnerable people in the state?

Johnson: I have a hard time. As a person of faith, it’s so hypocritical to me, because when you look at the 10 commandments, Jesus teaches that all of those commandments can be boiled down to two. The first is loving God, but the second one is loving your neighbor as yourself. And if I love my neighbor, then I recognize that we have a mutual interest in each other doing well.

That’s not something that I readily see in a hospitality state like Mississippi. So that’s hard for me to square for myself personally, but I also recognize that we’re all at different places in our walk of faith. I think if you’re Christian, you walk the walk of Christ long enough at some point, it changes your heart, and it begins to alter the way you see those around you, so I have hope that one day they’ll see that change.

But until that day, it just means that those of us who do see the need for change, need to not only be vocal, but need to be out front with doing those acts of compassion, of grace and mercy.

MT: If you were to explain what Medicaid expansion is to someone who wasn’t familiar with it, or someone who opposes it, what would you say about the policy and its significance?

Johnson: I’ve been holding on to a passage in Psalms 23 which says that “though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me.” It’s not that we don’t have something to fear, but Christ is with us. Christ is with the hurting. And to say that we are Christ’s followers means that we need to follow Christ to where those who are hurting to help, to offer grace, to offer support.

And I see access to health care as a means of offering grace to people, or expanding Medicaid, bridging the gap — whatever phrase people want to put to it.

MT: Together for Hope advocates for expansion because of their work in communities of poverty, as I understand it, so can you talk a little bit about the connection between poverty and poor health outcomes?

Johnson: If people are not getting the medical care they need, the health disparities are going off the charts. People are dying unnecessarily because they don’t even have the option of going to the doctor when they need it. When they get sick, they have to just muster through it and hope that they’ll be okay. And I don’t think that’s what it means to live in a community.

MT: If Mississippi continues to forgo expansion, what are the consequences for the communities you work with?

Johnson: Those health outcomes will continue to get worse and worse is the short answer. But I don’t think that robs compassionate people of ingenuity. We’re going to find a way to help people.

Expansion seems the most logical way that it can be done, but if we have to find an I’ll-climb-the-mountain-side way of helping people with health care access, we will.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Mississippi prepares for another execution

The Mississippi Supreme Court has set the execution of a man who kidnapped and murdered a 20-year-old community college student in north Mississippi 30 years ago.

Charles Ray Crawford, 59, is set to be executed Oct. 15 at the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, after multiple requests by the attorney general’s office.

Eight justices joined the majority opinion to set the execution, concluding that Crawford has exhausted all state and federal legal remedies. Mississippi Supreme Court Justice T. Kenneth Griffis Jr. wrote the Friday opinion. Justice David Sullivan did not participate.

However, Kristy Noble with the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel released a statement saying it will file another appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court.

“”Mr. Crawford’s inexperienced trial counsel conceded his guilt to the jury — against Mr.

Crawford’s timely and repeated objections,” Noble said in the statement. “Mr. Crawford told his counsel to pursue a not guilty verdict. Counsel did just the opposite, which is precisely what the U.S. Supreme Court says counsel cannot do,” Noble said in the statement.

“A trial like Mr. Crawford’s – one where counsel concedes guilt over his client’s express wishes – is essentially no trial at all.”

Last fall, Crawford’s attorneys asked the court not to set an execution date because he hadn’t exhausted appeal efforts in federal court to challenge a rape conviction that is not tied to his death sentence. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to take up Crawford’s case.

A similar delay occurred a decade ago, when the AG’s office asked the court to reset Crawford’s execution date, but that was denied because efforts to appeal his unrelated rape conviction were still pending.

After each unsuccessful filing, the attorney general’s office asked the Mississippi Supreme Court to set Crawford’s execution date.

On Friday, the court also denied Crawford’s third petition for post-conviction relief and a request for oral argument. It accepted the state’s motion to dismiss the petition. Seven justices concurred and Justice Leslie King concurred in result only. Again, Justice Sullivan did not participate.

Crawford was convicted and sentenced to death in Lafayette County for the 1993 rape and murder of North Mississippi Community College student Kristy Ray.

Days before he was set to go to trial on separate aggravated assault and rape charges, he kidnapped Ray from her parents’ Tippah County home, leaving ransom notes. Crawford took Ray to an abandoned barn where he stabbed her, and his DNA was found on her, indicating he sexually assaulted her, according to court records.

Crawford told police he had blackouts and only remembered parts of the crime, but not killing Ray. Later he admitted “he must of killed her” and led police to Ray’s body, according to court records.

At his 1994 trial he presented an insanity defense, including that he suffered from psychogenic amnesia – periods of time lapse without memory. Medical experts who provided rebuttal testimony said Crawford didn’t have psychogenic amnesia and didn’t show evidence of bipolar illness.

The last person executed in Mississippi was Richard Jordan in June, previously the state’s oldest and longest serving person on death row.

There are 36 people on death row, according to records from the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

Update 9/15/25: This story has been updated to include a response from the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Counsel

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Mississippi prepares for another execution appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a factual and balanced account of the legal proceedings surrounding a scheduled execution in Mississippi. It includes perspectives from both the state’s attorney general’s office and the defense counsel, without using emotionally charged language or advocating for a particular political stance. The focus on legal details and court decisions reflects a neutral, informative approach typical of centrist reporting.

Mississippi Today

Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing

TYLERTOWN — As an ominous storm approached Buddy Anthony’s one-story brick home, he took shelter in his new Ford F-250 pickup parked under a nearby carport.

Seconds later, a tornado tore apart Anthony’s home and damaged the truck while lifting it partly in the air. Anthony emerged unhurt. But he had to replace his vehicle with a used truck that became his home while waiting for President Donald Trump to issue a major disaster declaration so that federal money would be freed for individuals reeling from loss. That took weeks.

“You wake up in the truck and look out the windshield and see nothing. That’s hard. That’s hard to swallow,” Anthony said.

Disaster survivors are having to wait longer to get aid from the federal government, according to a new Associated Press analysis of decades of data. On average, it took less than two weeks for a governor’s request for a presidential disaster declaration to be granted in the 1990s and early 2000s. That rose to about three weeks during the past decade under presidents from both major parties. It’s taking more than a month, on average, during Trump’s current term, the AP found.

The delays mean individuals must wait to receive federal aid for daily living expenses, temporary lodging and home repairs. Delays in disaster declarations also can hamper recovery efforts by local officials uncertain whether they will receive federal reimbursement for cleaning up debris and rebuilding infrastructure. The AP collaborated with Mississippi Today and Mississippi Free Press on the effects of these delays for this report.

“The message that I get in the delay, particularly for the individual assistance, is that the federal government has turned its back on its own people,” said Bob Griffin, dean of the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity at the University at Albany in New York. “It’s a fundamental shift in the position of this country.”

The wait for disaster aid has grown as Trump remakes government

The Federal Emergency Management Agency often consults immediately with communities to coordinate their initial disaster response. But direct payments to individuals, nonprofits and local governments must wait for a major disaster declaration from the president, who first must receive a request from a state, territory or tribe. Major disaster declarations are intended only for the most damaging events that are beyond the resources of states and local governments.

Trump has approved more than two dozen major disaster declarations since taking office in January, with an average wait of almost 34 days after a request. That ranged from a one-day turnaround after July’s deadly flash flooding in Texas to a 67-day wait after a request for aid because of a Michigan ice storm. The average wait is up from a 24-day delay during his first term and is nearly four times as long as the average for former Republican President George H.W. Bush, whose term from 1989-1993 coincided with the implementation of a new federal law setting parameters for disaster determinations.

The delays have grown over time, regardless of the party in power. Former Democratic President Joe Biden, in his last year in office, averaged 26 days to declare major disasters — longer than any year under former Democratic President Barack Obama.

FEMA did not respond to the AP’s questions about what factors are contributing to the trend.

Others familiar with FEMA noted that its process for assessing and documenting natural disasters has become more complex over time. Disasters have also become more frequent and intense because of climate change, which is mostly caused by the burning of fuels such as gas, coal and oil.

The wait for disaster declarations has spiked as Trump’s administration undertakes an ambitious makeover of the federal government that has shed thousands of workers and reexamined the role of FEMA. A recently published letter from current and former FEMA employees warned the cuts could become debilitating if faced with a large-enough disaster. The letter also lamented that the Trump administration has stopped maintaining or removed long-term planning tools focused on extreme weather and disasters.

Shortly after taking office, Trump floated the idea of “getting rid” of FEMA, asserting: “It’s very bureaucratic, and it’s very slow.”

FEMA’s acting chief suggested more recently that states should shoulder more responsibility for disaster recovery, though FEMA thus far has continued to cover three-fourths of the costs of public assistance to local governments, as required under federal law. FEMA pays the full cost of its individual assistance.

Former FEMA Administrator Pete Gaynor, who served during Trump’s first term, said the delay in issuing major disaster declarations likely is related to a renewed focus on making sure the federal government isn’t paying for things state and local governments could handle.

“I think they’re probably giving those requests more scrutiny,” Gaynor said. “And I think it’s probably the right thing to do, because I think the (disaster) declaration process has become the ‘easy button’ for states.”

The Associated Press on Monday received a statement from White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson in response to a question about why it is taking longer to issue major natural disaster declarations:

“President Trump provides a more thorough review of disaster declaration requests than any Administration has before him. Gone are the days of rubber stamping FEMA recommendations – that’s not a bug, that’s a feature. Under prior Administrations, FEMA’s outsized role created a bloated bureaucracy that disincentivized state investment in their own resilience. President Trump is committed to right-sizing the Federal government while empowering state and local governments by enabling them to better understand, plan for, and ultimately address the needs of their citizens. The Trump Administration has expeditiously provided assistance to disasters while ensuring taxpayer dollars are spent wisely to supplement state actions, not replace them.”

In Mississippi, frustration festered during wait for aid

The tornado that struck Anthony’s home in rural Tylertown on March 15 packed winds up to 140 mph. It was part of a powerful system that wrecked homes, businesses and lives across multiple states.

Mississippi’s governor requested a federal disaster declaration on April 1. Trump granted that request 50 days later, on May 21, while approving aid for both individuals and public entities.

On that same day, Trump also approved eight other major disaster declarations for storms, floods or fires in seven other states. In most cases, more than a month had passed since the request and about two months since the date of those disasters.

If a presidential declaration and federal money had come sooner, Anthony said he wouldn’t have needed to spend weeks sleeping in a truck before he could afford to rent the trailer where he is now living. His house was uninsured, Anthony said, and FEMA eventually gave him $30,000.

In nearby Jayess in Lawrence County, Dana Grimes had insurance but not enough to cover the full value of her damaged home. After the eventual federal declaration, Grimes said FEMA provided about $750 for emergency expenses, but she is now waiting for the agency to determine whether she can receive more.

“We couldn’t figure out why the president took so long to help people in this country,” Grimes said. “I just want to tie up strings and move on. But FEMA — I’m still fooling with FEMA.”

Jonathan Young said he gave up on applying for FEMA aid after the Tylertown tornado killed his 7-year-old son and destroyed their home. The process seemed too difficult, and federal officials wanted paperwork he didn’t have, Young said. He made ends meet by working for those cleaning up from the storm.

“It’s a therapy for me,” Young said, “to pick up the debris that took my son away from me.”

Historically, presidential disaster declarations containing individual assistance have been approved more quickly than those providing assistance only to public entities, according to the AP’s analysis. That remains the case under Trump, though declarations for both types are taking longer.

About half the major disaster declarations approved by Trump this year have included individual assistance.

Some people whose homes are damaged turn to shelters hosted by churches or local nonprofit organizations in the initial chaotic days after a disaster. Others stay with friends or family or go to a hotel, if they can afford it.

But some insist on staying in damaged homes, even if they are unsafe, said Chris Smith, who administered FEMA’s individual assistance division under three presidents from 2015-2022. If homes aren’t repaired properly, mold can grow, compounding the recovery challenges.

That’s why it’s critical for FEMA’s individual assistance to get approved quickly — ideally, within two weeks of a disaster, said Smith, who’s now a disaster consultant for governments and companies.

“You want to keep the people where they are living. You want to ensure those communities are going to continue to be viable and recover,” Smith said. “And the earlier that individual assistance can be delivered … the earlier recovery can start.”

In the periods waiting for declarations, the pressure falls on local officials and volunteers to care for victims and distribute supplies.

In Walthall County, where Tylertown is, insurance agent Les Lampton remembered watching the weather news as the first tornado missed his house by just an eighth of a mile. Lampton, who moonlights as a volunteer firefighter, navigated the collapsed trees in his yard and jumped into action. About 45 minutes later, the second tornado hit just a mile away.

“It was just chaos from there on out,” Lampton said.

Walthall County, with a population of about 14,000, hasn’t had a working tornado siren in about 30 years, Lampton said. He added there isn’t a public safe room in the area, although a lot of residents have ones in their home.

Rural areas with limited resources are hit hard by delays in receiving funds through FEMA’s public assistance program, which, unlike individual assistance, only reimburses local entities after their bills are paid. Long waits can stoke uncertainty and lead cost-conscious local officials to pause or scale-back their recovery efforts.

In Walthall County, officials initially spent about $700,000 cleaning up debris, then suspended the cleanup for more than a month because they couldn’t afford to spend more without assurance they would receive federal reimbursement, said county emergency manager Royce McKee. Meanwhile, rubble from splintered trees and shattered homes remained piled along the roadside, creating unsafe obstacles for motorists and habitat for snakes and rodents.

When it received the federal declaration, Walthall County took out a multimillion-dollar loan to pay contractors to resume the cleanup.

“We’re going to pay interest and pay that money back until FEMA pays us,” said Byran Martin, an elected county supervisor. “We’re hopeful that we’ll get some money by the first of the year, but people are telling us that it could be [longer].”

Lampton, who took after his father when he joined the volunteer firefighters 40 years ago, lauded the support of outside groups such as Cajun Navy, Eight Days of Hope, Samaritan’s Purse and others. That’s not to mention the neighbors who brought their own skid steers and power saws to help clear trees and other debris, he added.

“That’s the only thing that got us through this storm, neighbors helping neighbors,” Lampton said. “If we waited on the government, we were going to be in bad shape.”

Lieb reported from Jefferson City, Missouri, and Wildeman from Hartford, Connecticut.

Update 98/25: This story has been updated to include a White House statement released after publication.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Presidents are taking longer to declare major natural disasters. For some, the wait is agonizing appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical view of the Trump administration’s handling of disaster declarations, highlighting delays and their negative impacts on affected individuals and communities. It emphasizes concerns about government downsizing and reduced federal support, themes often associated with center-left perspectives that favor robust government intervention and social safety nets. However, it also includes statements from Trump administration officials defending their approach, providing some balance. Overall, the tone and framing lean slightly left of center without being overtly partisan.

Mississippi Today

Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina

The 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina slamming the Mississippi Gulf Coast has come and gone, rightfully garnering considerable media attention.

But still undercovered in the 20th anniversary saga of the storm that made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, and caused unprecedented destruction is the role that a worm farmer from northeast Mississippi played in helping to revitalize the Coast.

House Speaker Billy McCoy, who died in 2019, was a worm farmer from the Prentiss, not Alcorn County, side of Rienzi — about as far away from the Gulf Coast as one could be in Mississippi.

McCoy grew other crops, but a staple of his operations was worm farming.

Early after the storm, the House speaker made a point of touring the Coast and visiting as many of the House members who lived on the Coast as he could to check on them.

But it was his action in the forum he loved the most — the Mississippi House — that is credited with being key to the Coast’s recovery.

Gov. Haley Barbour had called a special session about a month after the storm to take up multiple issues related to Katrina and the Gulf Coast’s survival and revitalization. The issue that received the most attention was Barbour’s proposal to remove the requirement that the casinos on the Coast be floating in the Mississippi Sound.

Katrina wreaked havoc on the floating casinos, and many operators said they would not rebuild if their casinos had to be in the Gulf waters. That was a crucial issue since the casinos were a major economic engine on the Coast, employing an estimated 30,000 in direct and indirect jobs.

It is difficult to fathom now the controversy surrounding Barbour’s proposal to allow the casinos to locate on land next to the water. Mississippi’s casino industry that was birthed with the early 1990s legislation was still new and controversial.

Various religious groups and others had continued to fight and oppose the casino industry and had made opposition to the expansion of gambling a priority.

Opposition to casinos and expansion of casinos was believed to be especially strong in rural areas, like those found in McCoy’s beloved northeast Mississippi. It was many of those rural areas that were the homes to rural white Democrats — now all but extinct in the Legislature but at the time still a force in the House.

So, voting in favor of casino expansion had the potential of being costly for what was McCoy’s base of power: the rural white Democrats.

Couple that with the fact that the Democratic-controlled House had been at odds with the Republican Barbour on multiple issues ranging from education funding to health care since Barbour was inaugurated in January 2004.

Barbour set records for the number of special sessions called by the governor. Those special sessions often were called to try to force the Democratic-controlled House to pass legislation it killed during the regular session.

The September 2005 special session was Barbour’s fifth of the year. For context, current Gov. Tate Reeves has called four in his nearly six years as governor.

There was little reason to expect McCoy to do Barbour’s bidding and lead the effort in the Legislature to pass his most controversial proposal: expanding casino gambling.

But when Barbour ally Lt. Gov. Amy Tuck, who presided over the Senate, refused to take up the controversial bill, Barbour was forced to turn to McCoy.

The former governor wrote about the circumstances in an essay he penned on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina for Mississippi Today Ideas.

“The Senate leadership, all Republicans, did not want to go first in passing the onshore casino law,” Barbour wrote. “So, I had to ask Speaker McCoy to allow it to come to the House floor and pass. He realized he should put the Coast and the state’s interests first. He did so, and the bill passed 61-53, with McCoy voting no.

“I will always admire Speaker McCoy, often my nemesis, for his integrity in putting the state first.”

Incidentally, former Rep. Bill Miles of Fulton, also in northeast Mississippi, was tasked by McCoy with counting, not whipping votes, to see if there was enough support in the House to pass the proposal. Not soon before the key vote, Miles said years later, he went to McCoy and told him there were more than enough votes to pass the legislation so he was voting no and broached the idea of the speaker also voting no.

It is likely that McCoy would have voted for the bill if his vote was needed.

Despite his no vote, the Biloxi Sun Herald newspaper ran a large photo of McCoy and hailed the Rienzi worm farmer as a hero for the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Northeast Mississippi speaker and worm farmer played key role in Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a factual and balanced account of the political dynamics surrounding Hurricane Katrina recovery efforts in Mississippi, focusing on bipartisan cooperation between Democratic and Republican leaders. It highlights the complexities of legislative decisions without overtly favoring one party or ideology, reflecting a neutral and informative tone typical of centrist reporting.

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Zaxby's Player of the Week: Dylan Jackson, Vigor WR

-

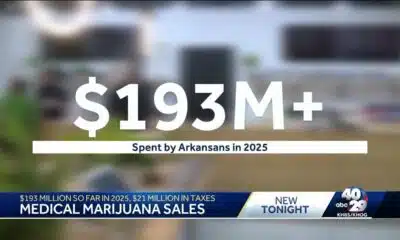

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

Arkansas medical marijuana sales on pace for record year

-

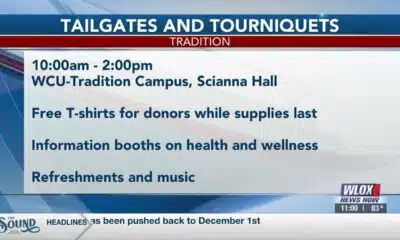

Local News Video7 days ago

William Carey University holds 'tailgates and tourniquets' blood drive

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

What we know about Charlie Kirk shooting suspect, how he was caught

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Local, statewide officials react to Charlie Kirk death after shooting in Utah

-

Local News7 days ago

US stocks inch to more records as inflation slows and Oracle soars

-

Local News6 days ago

Russian drone incursion in Poland prompts NATO leaders to take stock of bigger threats