Mississippi Today

Jailed for their own safety, 14 Mississippians died awaiting mental health treatment

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Mississippi Today. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Butch Scipper is haunted by the deaths of three men.

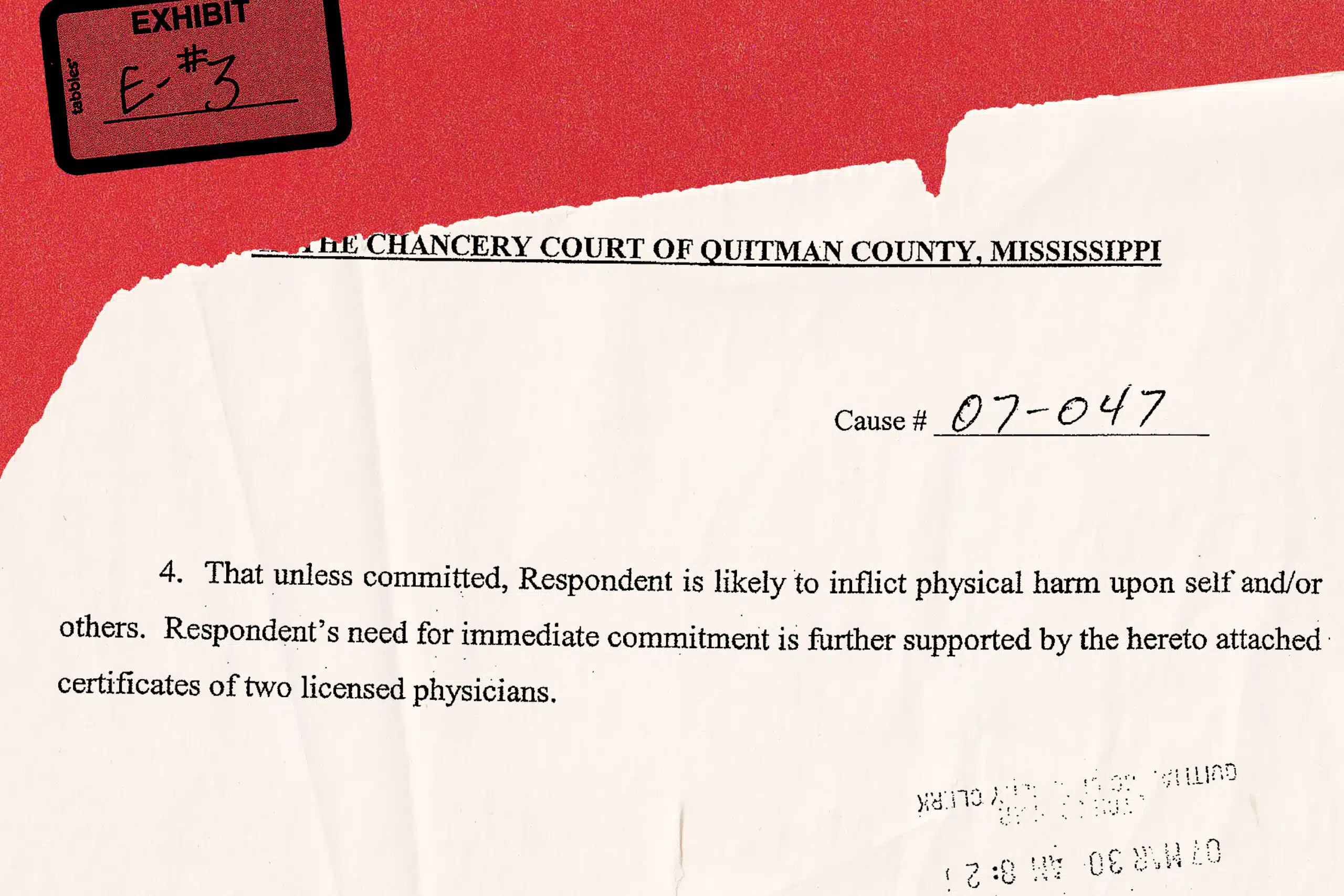

As chancery clerk of Quitman County in the Mississippi Delta, he coordinates a legal process in which people are ordered into treatment for serious mental illness or substance abuse — a common way for Mississippians, especially poor people without insurance, to access inpatient care.

Dozens of times a year, people ask Scipper for help because they are afraid sick family members will hurt themselves or others. Up until a few years ago, he sent many of those family members to jail as they waited to be evaluated and treated.

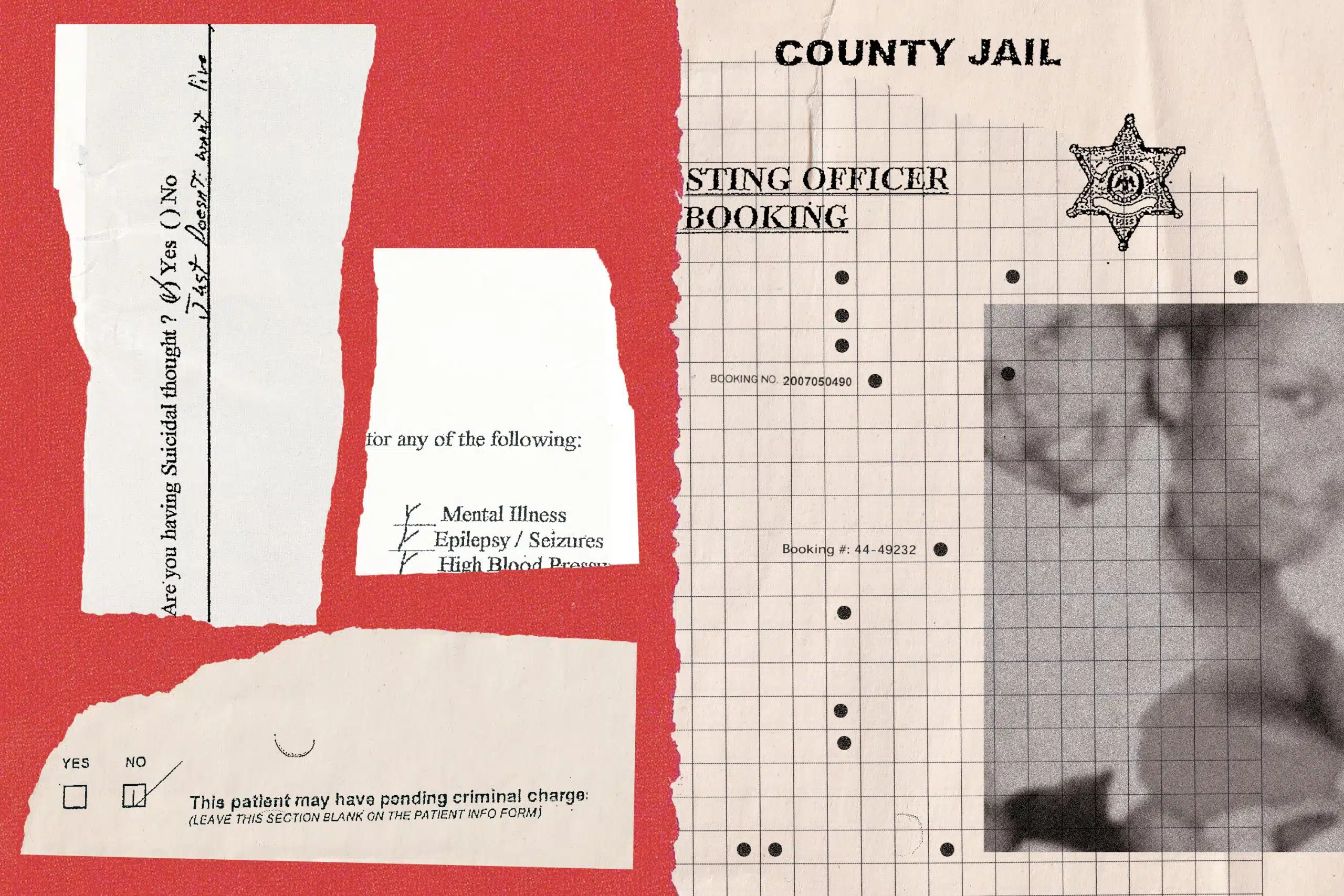

Jailing people with no criminal charges during the civil commitment process is common in Mississippi because many county officials see no other option when publicly funded mental health facilities are unavailable. In jail, Scipper figured, people going through the commitment process would be prevented from harming themselves or others.

Yet three men — Tyrone Compton, Brandon Raymond and Brian Sneed — killed themselves in the Quitman County jail. Compton and Raymond died the same way, in the same cell, just seven months apart in 2006 and 2007. Sneed died in 2019.

“These three guys run back and forth across my head,” Scipper said. Sending them to jail, he now believes, “was not the right thing to do.”

Since 2006, at least 14 Mississippians have died after being placed in jail during the civil commitment process, purportedly for their own safety. Nine of them, including those three men, died by suicide. Twelve had not been charged with a crime.

It’s not easy to know what goes on inside Mississippi jails — unlike in many states, they’re not subject to mandatory health and safety standards — but lawsuits and Mississippi Bureau of Investigation reports provide some visibility.

Mississippi Today and ProPublica read sworn testimony by family members, jail staffers, administrators, sheriffs and other inmates regarding deaths in jail during the commitment process. We reviewed medical and jail records. We compared suicide prevention policies to nationally recognized guidelines. And we shared key facts about these cases or the policies in effect at the time with a dozen experts in correctional health care, including psychiatrists and other physicians.

Before 11 of the deaths, the medical care and suicide prevention measures fell short of national standards, sometimes shockingly so, according to experts and a review of those standards. (The care provided before the other three deaths, including the most recent one in August, is unclear.)

Before most of the nine suicides, staff didn’t take some basic steps to prevent people from killing themselves, according to those experts and nationally accepted guidelines. And when people going through the commitment process exhibited serious medical issues, jail staff didn’t get them the help they needed, experts said after reviewing the circumstances of those deaths drawn from a Mississippi Bureau of Investigation report, depositions and records filed in court. Staff didn’t review medical histories. They interpreted signs of medical distress as manifestations of mental illness or the influence of drugs or alcohol. They failed to act.

“When you see somebody that ain’t eating, you can’t just let them sit there and do that. … They’re still somebody. They’re still a human being.”

Terry Fox, husband of Nakema Fox, who died of a pulmonary embolism in jail

Local officials in Mississippi say they sometimes need to jail people during the commitment process to keep them safe. But according to the experts we interviewed, jails not only fail to guarantee safety for people with serious mental illness, they can be particularly dangerous for them.

“There’s a whole lot more to safety than just bars and shackles,” said Dr. Robert Greifinger, the former chief medical officer for the New York state prison system.

That point has long been made by sheriffs and jail administrators in Mississippi, too. In 1999, for instance, a 43-year-old man killed himself in the Union County jail as he waited to be taken to Mississippi State Hospital near Jackson for psychiatric treatment.

“He was under watch, but you can’t watch him every minute,” Joe Bryant, then sheriff of the north Mississippi county, said at the time. “It just brings to light a problem that county jails face: There should be some means besides a county jail to house mental patients. A jail is not equipped for this.”

Nearly a quarter-century later, the problem persists. A law passed in 2009 requiring jails to meet state standards if they hold people awaiting psychiatric treatment has resulted in just one jail that’s certified among the 71 that detained about 800 such people in the year ending in June 2023.

When someone dies in jail awaiting treatment, litigation is the primary way families can try to hold officials accountable. Yet none of the nine lawsuits filed over deaths since 2006 have resulted in a court ruling that held county or jail officials responsible. Four were settled. One is ongoing. The rest were dismissed or lost at trial.

Legal experts say such suits rarely succeed, in part because it’s so hard to prove that jail medical care was so bad that it violated someone’s constitutional rights.

But the failure to meet a legal standard doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem. Correctional health care experts said Mississippi’s practice of jailing people solely because they’re mentally ill or addicted to drugs or alcohol has caused deaths that could have been prevented.

“It’s taking people with a suspected health problem and putting them in a place that is likely going to increase their risk of dying from that health problem. The health risks of jail are well established, and they include suicide,” said Dr. Homer Venters, former chief medical officer of New York City jails.

“It’s a terrifying practice.”

Unwatched and Unprotected

After Scipper took office as Quitman County chancery clerk in 1992, he started handling up to 100 civil commitments a year. He instructed family members on how to file the paperwork, waited for judges to order people into treatment and, if families didn’t want them at home, figured out where to hold them in the meantime. “We used to just automatically put them in the jailhouse,” he said.

In 2006, a man came to Scipper’s office to file commitment papers after his son attacked him. The father was concerned the young man, Tyrone Compton, would hurt himself. Later that day, Compton hanged himself from a set of bars mounted in front of a window in his cell.

Seven months later, Brandon Raymond hanged himself from the same bars as he waited to be taken to a state hospital for drug rehab. It wasn’t until after his death that a piece of metal was welded onto the bars, even though the jail administrator had warned county officials about the danger after the first suicide, according to a deposition in a lawsuit filed over Raymond’s death.

It was an obvious shortcoming. For years, suicide was the leading cause of death in U.S. jails, primarily from hanging. Long-accepted standards direct jail staff to keep people who are at risk of suicide away from bars or protrusions.

A review of court filings and investigations related to the suicides points to shortcomings in how people going through the commitment process were screened for suicide risk, where they were held and how they were monitored.

Suicide prevention policies that address these issues have long been recognized as an essential element of jail medical care. But the former Quitman County jail administrator testified that he didn’t know about any policies whatsoever at the time of Compton and Raymond’s deaths.

David Fathi, an attorney who has worked on litigation over jail and prison conditions for more than 25 years and now serves as director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, reviewed suicide prevention policies that were in effect at five Mississippi jails where several people died by suicide. Some, he said, were “among the worst policies I’ve ever seen.” One policy said staff could turn off water in a cell to reduce the risk of self-harm — a practice Fathi said has resulted in deaths by dehydration of people with mental illness.

“To send people to jail because they have mental illness, and to send them to a jail that has either flagrantly inadequate suicide policies or no suicide policy at all, is a recipe for disaster,” Fathi said.

If you or someone you know needs help:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

Screening inmates for suicide risk is a key part of such policies, and it’s a standard part of the booking process at jails across the country. Staff should ask inmates multiple questions, ranging from explicit ones about whether they have considered suicide to less direct ones like “Have you ever wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?”

At least six of the nine people who killed themselves, including Compton and Raymond, weren’t screened at all or underwent screenings that didn’t meet national standards, according to depositions and jail records.

For nearly three years after Raymond died without being screened, staff still did not conduct screenings for medical or psychiatric issues, according to depositions. Jail policy had required such screenings for years, but employees, including the former jail administrator, didn’t know that, according to depositions.

Quitman County’s current medical questionnaire does ask staff to determine whether the inmate is “so disoriented or mentally confused as to suggest the risk of suicide,” but leaders in correctional health care told Mississippi Today and ProPublica that’s not sufficient.

“I can still see Brandon in my yard. I can still see Brandon coming in my front door. I’ve lost my daddy, and I’ve lost my mama, but it’s nothing like my baby.”

Sandra Pruitt, mother of Brandon Raymond, in a deposition

Compton’s father and Raymond’s mother filed lawsuits against Quitman County, the sheriff and sheriff’s department staff. In response to the Compton lawsuit, the defendants argued they were shielded by qualified immunity, a doctrine that protects government officials from liability for violations of constitutional rights that are not clearly established. They also argued that Compton’s death was the result of his own conduct and that even if his rights had been violated, it wouldn’t have been due to a county policy.

In response to the Raymond lawsuit, defendants argued that qualified immunity applied, jail staff had no reason to believe Raymond was at risk of suicide, and no county policy led to a violation of his rights.

Quitman County settled both lawsuits for undisclosed sums. The sheriff and county officials other than Scipper did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Once people are booked into jail, there are nationally accepted guidelines on what staff should do to prevent people from killing themselves.

People who are seriously mentally ill are “naturally at higher risk for suicide,” said Dr. Brent Gibson, former chief health officer at the National Commission on Correctional Health Care and founder of the health care consulting company Avocet Enterprises. “All of these people should be directly observed in some kind of way.”

Staff should check on people at risk of suicide at irregular intervals of no more than 15 minutes, according to standards developed by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. People who are trying to hurt themselves or say they plan to do so should be watched constantly. At-risk inmates should be housed in cells that are “suicide-resistant.” If necessary, their clothes and bedding should be replaced with smocks and blankets made of thick, sturdy material.

Before all nine suicides in Mississippi jails, those things didn’t happen — in part because at least two inmates were never screened in the first place — according to depositions, Mississippi Bureau of Investigation reports and jail records. Just one person was put on suicide watch and housed in a suicide-resistant cell. At least eight weren’t monitored as frequently as guidelines say. At least seven of the eight who hanged themselves weren’t provided with special clothing or blankets. At one jail, the policy was to put someone on suicide watch only if they had attempted suicide there.

Quitman County Sheriff Oliver Parker said in a deposition that his staff did not keep an especially close eye on Raymond because his commitment did not stem from a suicide attempt.

In 2019, 12 years after Raymond died, Brian Sneed was booked into the Quitman County jail without criminal charges as he awaited a drug rehab bed. When the 52-year-old welder was discovered dead from suicide, it had been more than an hour since jail staff had checked on him, according to a Mississippi Bureau of Investigation report.

“They may die out on the street — I can’t say they don’t. But in a jail cell is just not a good spot for them.”

Quitman County Chancery Clerk Butch Scipper

After Sneed’s death, Scipper concluded he couldn’t guarantee people waiting for treatment would be safe in jail. “I said right then, they may die out on the street — I can’t say they don’t,” he said in an interview. “But in a jail cell is just not a good spot for them.”

Now, he tells people to wait at home until a publicly funded treatment bed is available. Nothing in state law prohibits that, though the state Department of Mental Health says people who are well enough to wait at home may not actually need to be committed.

When The Doctor’s Waiting Room is a Jail Cell

The bare-bones medical care in many Mississippi jails can be dangerous for people who are mentally ill even if they aren’t suicidal.

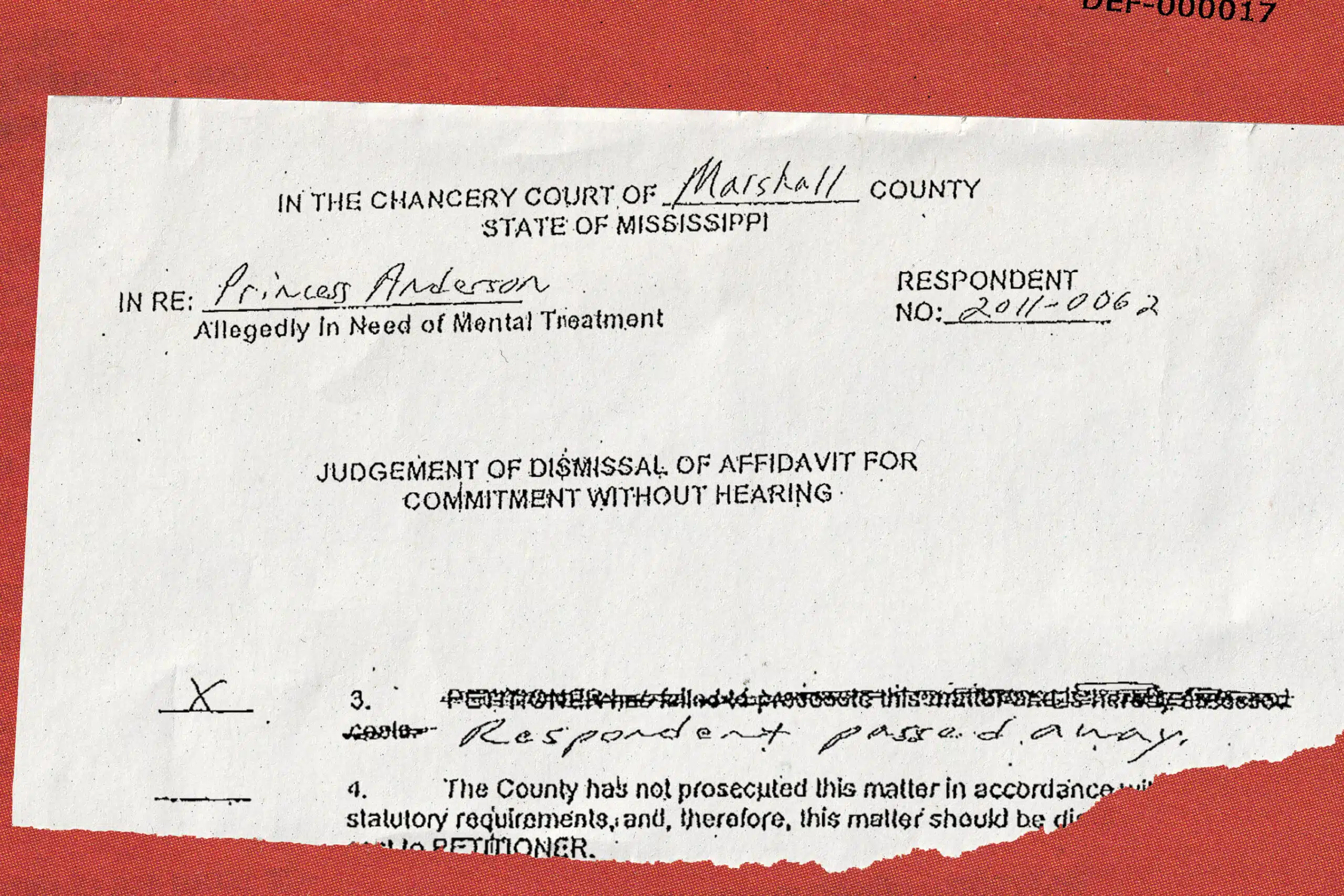

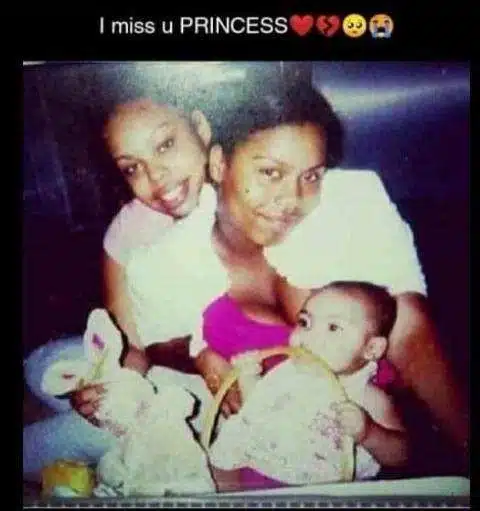

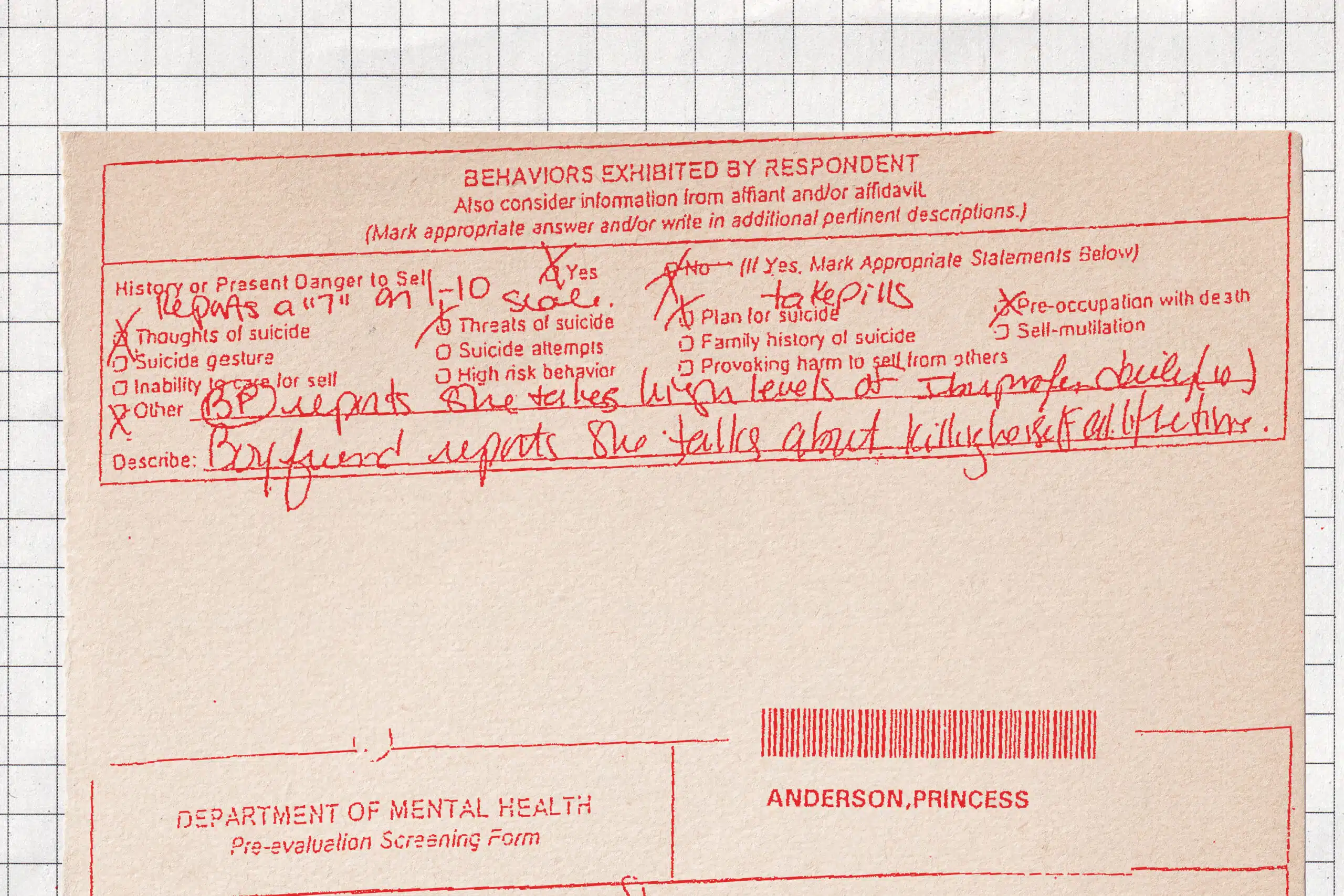

Over the three days that Princess Anderson was held in the Marshall County jail awaiting a commitment hearing in February 2011, her physical condition declined precipitously. Jail staff did little to inquire about her medical history, according to depositions in a lawsuit later filed over her death. And staff failed to call for help as she exhibited signs of medical distress.

“I would never ever thought in my life that anything like this would ever go on, you know, what happened to my child. … They’re supposed to be protecting you. They supposed to be caring for you.”

Angela Anderson, mother of Princess Anderson

By the time Anderson arrived at a hospital, “she may very well have been one of the sickest patients I’ve ever seen,” her attending physician in the intensive care unit testified in that lawsuit.

Anderson’s journey through the commitment process had started four days before, when she went to a hospital near Memphis and learned she might be suffering from an ectopic pregnancy, a painful and possibly fatal condition. She was released but later that day went to Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto, where she reported that she had ingested cough syrup and marijuana and complained of nausea and anxiety. After she shoved nurses and screamed that she was going to die, a mental health assessor working on behalf of the hospital filed paperwork to have her involuntarily committed.

Anderson was taken in shackles from the hospital to the jail in neighboring Marshall County, where she lived, to await a psychiatric evaluation. On one jail document, her “most serious charge” was recorded as “LUNACY.”

Booking officer Adella Anderson, who is not related to Princess Anderson, handled the medical screening. Princess Anderson didn’t respond to her questions, so the booking officer later testified that she filled out the screening form with the limited information in the commitment paperwork.

Experts said the booking officer should not have simply stopped her inquiries because Anderson didn’t respond; she should have asked a mental health professional to gather more information.

The booking officer testified that she knew Anderson had been brought from a hospital but didn’t find out why. She said she didn’t open an envelope containing Anderson’s medical records because she thought that was illegal. (The law allows correctional staff to review medical records if necessary, but experts said such staff should be trained in doing so, and she was not.) If she had opened the envelope, she might have seen hospital paperwork about the ectopic pregnancy.

Gibson said he has seen “numerous deaths” occur after a jail staffer gave up on a medical screening because an inmate didn’t provide information. “If someone is literally not responsive, they probably shouldn’t be in the jail at all — they should be in the hospital,” he said.

Efforts to reach Adella Anderson by email, phone and mail were unsuccessful.

The next day, an employee of Communicare, the local community mental health center, tried to evaluate Princess Anderson. Again, she was “unresponsive,” according to the form that therapist Debra Shelton filled out. Shelton used paperwork from the hospital to complete the form, concluding that Anderson had tried to harm herself after learning she was pregnant. “Recommend immediate transfer to hospital” for psychosis, Shelton wrote. (Efforts to reach her for this story were unsuccessful.)

Instead of being hospitalized, Anderson was left alone in her cell with inconsistent monitoring until she could be evaluated further as part of the commitment process.

If she had been in a state psychiatric hospital, medical professionals would have routinely checked her vital signs. That’s important because people with mental illness may not recognize signs of physical illness and ask for help, correctional health care experts said. In jail, however, none of the staff were required to have any medical training aside from CPR.

Over the next two days, Anderson’s condition became increasingly concerning to those around her — but not to jail staff, according to depositions.

She removed her clothes and, according to an inmate’s testimony, lay on the floor in a pool of water for hours at a time. “There wasn’t nothing abnormal for her to get on the floor,” the booking officer later testified. “Most lunacies do that.”

Anderson got sicker. She barely spoke. Her fingers bled from scratching the walls. When she foamed at the mouth, inmates beat on a cell block door for help and told jailers they thought she was having a seizure. Two inmates called 911. Even “the church people” who regularly came to the jail tried to get staff to call an ambulance, one inmate testified.

The booking officer later testified that she didn’t take those calls for help seriously. Inmates “do that with everybody,” she said.

Greifinger, the former chief medical officer for the New York state prison system, said that kind of thinking is common among correctional staff around the country. Even when they see an inmate vomiting or know someone hasn’t eaten for days, he said, “there’s a tremendous culture of disbelief that’s rampant.”

Meanwhile, Anderson’s mother, Angela Anderson, found hospital paperwork saying her daughter might have an ectopic pregnancy. Angela Anderson went to the courthouse to ask if she could take her daughter to a hospital for an ultrasound.

Sarah Liddy, the special master presiding over Princess Anderson’s commitment proceedings, allowed the young woman to leave the jail only after her mother signed a document promising to pay for her medical care. Liddy didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article.

When Angela Anderson arrived at the jail, she found a horrifying scene, according to her testimony. Her daughter was lying on the floor, in two inches of water, feces and vomit. Her fingernails were broken off and there was blood on the walls. Princess was unconscious, only able to groan. Angela begged jail staff to call 911, testifying later that she felt “like a fool” for calling for help from inside a jail.

Princess Anderson was admitted to an ICU with a diagnosis of psychosis, acute renal failure, a metabolic disorder and sepsis. She died a month later at the same hospital where staff had started the legal process that landed her in jail.

According to her autopsy report, Anderson may have experienced a miscarriage in jail. Based on the autopsy and the available information, a medical examiner concluded that she died from multisystem organ failure of an unknown cause.

Dr. Marc F. Stern, a professor at the University of Washington and former medical director for the Washington State Department of Corrections, reviewed key facts of Anderson’s case. He said the behavior that caused hospital staff to initiate commitment proceedings may have been caused by an underlying medical issue.

What happened to Anderson, he said, shows that Mississippi’s practice of jailing people who need medical care is “dangerous, unconscionable, and inhumane.”

‘Ignoble, Sordid, Upsetting, and Tragic.’ But Not Unconstitutional.

When Anderson died, her mother sued Marshall County and Sheriff Kenny Dickerson, as well as Baptist Memorial Hospital-DeSoto. Hers was one of at least nine lawsuits filed by families seeking to hold accountable the people who had detained their loved ones.

Outside of criminal charges, such lawsuits are typically the only option relatives have. Eight of those suits have run their course; none have resulted in court rulings holding anyone liable.

Unlike the vast majority of Americans, incarcerated people have a constitutional right to health care, thanks to a 1976 Supreme Court decision. But in order to prove that insufficient medical care violated an inmate’s constitutional rights, a plaintiff must demonstrate “deliberate indifference” — that staff knew an inmate needed medical attention or was at risk of suicide, but did little or nothing in response.

“That’s a super hard standard to meet,” said Michele Deitch, an expert on jail oversight and director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. “You have to get into the head of the person who caused harm,” she said. “They had to know there was a risk of serious harm, and then they did this thing anyway, not caring.”

Princess Anderson’s mother couldn’t meet that standard.

Her suit alleged the sheriff’s office was deliberately indifferent to Princess Anderson’s medical needs. Attorneys representing the sheriff and the county argued the sheriff was entitled to qualified immunity and that jail staff had taken measures to care for Anderson, pointing out that hospital staff had medically cleared her to be taken to jail. The sheriff and other county officials didn’t respond to inquiries for this article.

The suit also alleged that the hospital failed to diagnose the cause of Princess Anderson’s altered mental state and stabilize her and that it handed her over to deputies without proper instructions. In response, the hospital argued that it was protected by a provision of Mississippi law that says anyone “acting in good faith” during the civil commitment process can’t be held liable.

A federal judge dismissed the case against the sheriff based on qualified immunity. The county was later dismissed as a defendant because jail policies were not the “moving force” behind Anderson’s death and jail staff had “periodically” monitored her.

“Officers observed Anderson’s pattern of taking off her clothes and lying on the floor, but they found this conduct to be consistent with other mentally ill inmates at the jail,” U.S. District Judge Debra M. Brown wrote in her December 2014 opinion.

Angela Anderson appealed that decision to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. In their ruling, circuit judges called Princess Anderson’s death “ignoble, sordid, upsetting, and tragic.” But they agreed that Anderson’s mother had not proven that officials had acted with deliberate indifference.

All of the lawsuits filed over these deaths alleged the care provided in jail demonstrated deliberate indifference. In the three cases in which judges issued rulings, none found those arguments persuasive.

Anderson’s suit against the hospital eventually went to trial in state court. A jury sided with the hospital.

In an email, Baptist Memorial Health Care’s director of public relations, Kim Alexander, wrote of Princess Anderson, “I am confident our medical team did everything they could to help her and provide compassionate treatment while she was in our care.”

“We are saddened by outcomes like Ms. Anderson’s,” Alexander wrote, “and fully support efforts by our state and mental health professionals to refine our mental health system.”

Eight of the nine counties where people died as they went through the commitment process, including Marshall County, still jail those people. Quitman, where Scipper works, no longer does.

Do you have a story to share about someone who went through the civil commitment process in Mississippi? Contact Isabelle Taft at itaft@mississippitoday.org or call her at (601) 691-4756.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Brain drain: Mother understands her daughters’ decisions to leave Mississippi

Editor’s note: This Mississippi Today Ideas essay is published as part of our Brain Drain project, which seeks answers to Mississippi’s brain drain problem. To read more about the project, click here.

Back when I was a kid in 1988, my mama and I had an argument about what I wanted to major in at college.

I had dreamed of being a journalist since the age of 8. To me, that meant that I was going to Ole Miss, which had the journalism department.

My mama said I could only go away from home to Ole Miss if I was going to major in law.

So I settled on going to Mississippi State University just down the road and majoring in communication. She told me I should major in engineering since that’s what State was known for.

I said, “That’s even dumber than me going to law school. I hate math.”

“Well, you could at least try,” she said.

I said no. Then she told me I was wasting my education and turned her back on me.

I get it. She knew and I knew that I couldn’t stay in Choctaw County where I was raised and earn a living with that degree. I would have to go somewhere else — probably to the Jackson metro area and work for Gannett or the Associated Press. Or to Memphis. Or Biloxi. Or even New Orleans. She never really forgave me for moving to the Jackson metro, working in my field and raising her grandchildren so far from her.

After a while, I got used to the pace of life around here. I knew I probably wouldn’t ever move anywhere else because I noticed that people who left Mississippi often came back, whether due to family obligations or a realization that “somewhere else” wasn’t quite all it was cracked up to be.

I also noticed that a lot of people played up how they were from Mississippi while making a very good living being someplace else. I decided I wanted to prove you could be from Mississippi, live in Mississippi, work in Mississippi and make something of yourself without leaving Mississippi.

But I noticed something else over the years, too. Most of the kids in Brandon dreamed of going off from home to cities like Atlanta, Nashville, Dallas, DC, New York or Orlando. They didn’t seem to have reasons — just a desire to get away from the state as fast as they could.

Then my three daughters and I started having conversations about what they wanted to major in when they went to college. My oldest wanted to be a chef. My middle one was undecided between chemical engineering and landscape architecture. And my youngest was fascinated with roads and bridges.

I was all too aware of what had happened in the job markets in Mississippi since I had come up. Companies closed operations in a globalized economy and fled to cheaper labor markets. The advent of the internet meant employers could hire from all over the world. Longtime business leaders retired and sold out to big corporations that reduced investments in local communities that had supported those businesses for decades and then complained that those towns didn’t offer enough amenities for their employees to want to relocate there.

But the reality really set in when my chef daughter chose her first internship — in historic Williamsburg, Virginia.

I would never have dreamed of driving that far from home to try out a place to work when I was her age. Then after her senior year, she interned at Walt Disney World and got hired full-time before the internship was over. She was off to live in Orlando where now with her husband and young son she’s creating community and loves going to work every day with a pretty enviable benefits package, too, a thing unheard of in the culinary world in Mississippi.

My middle one finally settled on chemical engineering and was picked for a co-op job in her first semester at age 18 at a company in Georgia. When she graduated four years later, we packed her off to Indiana for a research and development job, and she now lives in New Hampshire with her husband, making six figures a year at 26 years old and looking forward to partaking in the cultural offerings in New York City when she can.

The youngest is currently in college for civil engineering, and I’m bracing myself for the inevitable. She doesn’t want to work for state government, so she’s likely going out of state as well. Her comment about coming back to Jackson metro was the most damning of all. “There’s nothing to do here,” she says.

A lot of people ask me questions: How often do you see your daughters? How can you stand being so far from your grandson? Don’t they at least come home for Christmas?

The answer to all of those questions is that we do the best we can. We text, we message on Facebook, we talk on the phone at least once a week, every Sunday. We arrange visits; sometimes it’s us driving to them while other times they drive to us.

I can’t imagine making my children as miserable as my mom made me over my life choices. We are flexible, understanding, and very, very proud of our daughters, who are grappling with enough in their lives without us loading them down with guilt over when they are coming home.

The calculus may change in the future. We may have declines in health and need to move closer to one of our children if we need assistance. Or we may need to be in assisted living care here in Mississippi where such care may be marginally cheaper than wherever our girls land.

But I don’t wish our girls had settled for life in Mississippi.

What I wish is that Mississippi could find a way to live up to its potential — to be a place more worthy of my daughters’ loyalty, affections and investment in themselves.

Maybe it will be someday. I hope so, for all of our sakes.

Julie Liddell Whitehead lives and writes from Mississippi. An award-winning freelance writer, Julie covered disasters from 9/11 to Hurricane Katrina throughout her career. Her first book is “Hurricane Baby: Stories,” published by Madville Publishing. She writes on mental health, mental health education and mental health advocacy. She has a bachelor’s degree in communication, with a journalism emphasis, and a master’s degree in English, both from Mississippi State University. In 2021, she completed her MFA from Mississippi University for Women.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Brain drain: Mother understands her daughters' decisions to leave Mississippi appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This essay reflects a Center-Left perspective by focusing on social and economic challenges faced by Mississippi, such as brain drain, job market changes, and community decline. The tone is empathetic and advocates for investment in local opportunities and amenities to retain talent, aligning with progressive concerns about economic inequality and regional development. However, it remains largely personal and reflective rather than explicitly ideological or partisan. The article critiques systemic economic shifts without advancing a polarized political agenda, emphasizing hope for future improvement and a more supportive environment for young professionals.

Mississippi Today

After 30 years in prison, Mississippi woman dies from cancer she says was preventable

Behind Bars, Beyond Care:

A Mississippi Today investigation into suffering, secrecy and the business of prison health care

Susie Balfour, diagnosed with terminal breast cancer two weeks before her release from prison, has died from the disease she alleged past and present prison health care providers failed to catch until it was too late.

The 64-year-old left the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in December 2021 after more than 30 years of incarceration. She died on Friday, a representative for her family confirmed.

Balfour is survived by family members and friends. News of her passing has led to an outpouring of condolences of support shared online from community members, including some she met in prison.

Instead of getting the chance to rebuild her life, Balfour was released with a death sentence, said Pauline Rogers, executive director of the RECH Foundation.

“Susie didn’t just survive prison, she came out fighting,” Rogers said in a statement. “She spent her final years demanding justice, not just for herself, but for the women still inside. She knew her time was limited, but her courage was limitless.”

Last year, Balfour filed a federal lawsuit against three private medical contractors for the prison system, alleging medical neglect. The lawsuit highlighted how she and other incarcerated women came into contact with raw industrial chemicals during cleaning duty. Some of the chemicals have been linked to an increased risk of cancer in some studies.

The companies contracted to provide health care to prisoners at the facility over the course of Balfour’s sentence — Wexford Health Sources, Centurion Health and VitalCore, the current medical provider — delayed or failed to schedule follow-up cancer screenings for Balfour even though they had been recommended by prison physicians, the lawsuit says.

“I just want everybody to be held accountable,” Balfour said of her lawsuit. “ … and I just want justice for myself and other ladies and men in there who are dealing with the same situation I am dealing with.”

Rep. Becky Currie, who chairs the House Corrections Committee, spoke to Balfour last week, just days before her death. Until the very end, Balfour was focused on ensuring her story would outlive her, that it would drive reforms protecting others from suffering the same fate, Currie said.

“She wanted to talk to me on her deathbed. She could hardly speak, but she wanted to make sure nobody goes through what she went through,” Currie said. “I told her she would be in a better place soon, and I told her I would do my best to make sure nobody else goes through this.”

During Mississippi’s 2025 legislative session, Balfour’s story inspired Rep. Justis Gibbs, a Democrat from Jackson, to introduce legislation requiring state prisons to provide inmates on work assignments with protective gear.

Gibbs said over 10 other Mississippi inmates have come down with cancer or become seriously ill after they were exposed to chemicals while on work assignments. In a statement on Monday, Gibbs said the bill was a critical step toward showing that Mississippi does not tolerate human rights abuses.

“It is sad to hear of multiple incarcerated individuals passing away this summer due to continued exposure of harsh chemicals,” Gibbs said. “We worked very hard last session to get this bill past the finish line. I am appreciative of Speaker Jason White and the House Corrections Committee for understanding how vital this bill is and passing it out of committee. Every one of my house colleagues voted yes. We cannot allow politics between chambers on unrelated matters to stop the passage of good common-sense legislation.”

The bill passed the House in a bipartisan vote before dying in the Senate. Currie told Mississippi Today on Monday that she plans on marshalling the bill through the House again next session.

Currie, a Republican from Brookhaven, said Balfour’s case shows that prison medical contractors don’t have strong enough incentives to offer preventive care or treat illnesses like cancer.

In response to an ongoing Mississippi Today investigation into prison health care and in comments on the House floor, Currie has said prisoners are sometimes denied life saving treatments. A high-ranking former corrections official also came forward and told the news outlet that Mississippi’s prison system is rife with medical neglect and mismanagement.

Mississippi Today also obtained text messages between current and former corrections department officials showing that the same year the state agreed to pay VitalCore $100 million in taxpayer funds to provide healthcare to people incarcerated in Mississippi prisons, a top official at the Department remarked that the company “sucks.”

Balfour was first convicted of murdering a police officer during a robbery in north Mississippi, and she was sentenced to death. The Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the conviction in 1992, finding that her constitutional rights were violated in trial. She reached a plea agreement for a lesser charge, her attorney said.

As of Monday, the lawsuit remains active, according to court records. Late last year Balfour’s attorneys asked for her to be able to give a deposition with the intent of preserving her testimony. She was scheduled to give one in Southaven in March.

Rogers said Balfour’s death is a tragic reminder of systemic failures in the prison system where routine medical care is denied, their labor is exploited and too many who are released die from conditions that went untreated while they were in state custody.

Her legacy is one RECH Foundation will honor by continuing to fight for justice, dignity and systemic reform, said Rogers, who was formerly incarcerated herself.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post After 30 years in prison, Mississippi woman dies from cancer she says was preventable appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical view of the Mississippi prison health care system, highlighting systemic failures and medical neglect that led to the death of a formerly incarcerated woman. The tone and framing focus on social justice issues, prisoner rights, and the need for government accountability and reform, which align with Center-Left values emphasizing government responsibility for vulnerable populations. While the article is largely investigative and fact-based, its emphasis on advocacy for reform, criticism of privatized prison health contractors, and highlighting bipartisan legislative efforts suggest a Center-Left leaning perspective rather than neutral reporting.

Mississippi Today

FBI concocted a bribery scheme that wasn’t, ex-interim Hinds sheriff says in appeal

Former interim Hinds County sheriff Marshand Crisler is appealing bribery and ammunition charges stemming from his 2021 campaign, arguing that the federal government played on his relationship with a former supporter to entrap him.

Crisler had asked Tonarri Moore, who donated to past campaigns, for a financial contribution for the sheriff’s race. Moore said he would donate if Crisler helped with several requests. Without the previous relationship, Crisler would not have acted, his attorney argues, and Crisler had no reason to believe he was being bribed.

“The government, having concocted a bribery scheme to entrap Crisler, then had to contrive a corresponding quid pro quo to support the scenario with which to entrap him,” attorney John Holliman wrote in a Saturday appellant brief.

Crisler is asking the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals to reverse his conviction and render its own rulings on both counts.

He was convicted in federal court in November after a three-day trial and sentenced earlier this year to 2 ½ years in prison. Crisler is serving time in FCI Beckley in West Virginia.

The day before Crisler reached out to Moore to ask for support for his campaign for sheriff, Drug and Enforcement Administration agents raided Moore’s home and found guns and drugs. An FBI agent called to the scene looked through Moore’s phone and saw Crisler had called.

According to the appellant brief, the agent asked Moore what Crisler would do if offered money, and if Moore was bribing him. Moore said he wasn’t bribing Crisler, and the agent asked if Moore would do it.

At that time, there weren’t reasonable grounds to start a bribery investigation into Crisler, his attorney argues, nor was there reason to believe he was seeking a bribe.

Moore agreed to become an informant for the FBI, in exchange for the government not prosecuting him for the guns and drugs.

The FBI fitted him with a wire to record Crisler during meetings, which began that day. The meetings included one inside Moore’s night club and a cigarette lounge in Jackson. Agents provided Moore with the $9,500 he gave to Crisler between September and November 2021.

Crisler’s 2023 indictment came as he campaigned again for sheriff and months before the primary election. He remained in the race and lost to the incumbent who he faced in 2021.

At trial, the government argued the exchange of money were attempts to bribe because Moore made several requests of Crisler: to move his cousin to a different part of the Hinds County Detention Center, to get him a job in the sheriff’s office and for Crisler to let Moore know if law enforcement was looking into his activities.

In closing arguments, Assistant U.S. Attorney Charles Kirkham pointed to examples of quid pro quo in recordings, including one where Moore said to Crisler, “You scratch my back, I scratch yours” and Crisler replied “Hello!” in a tone that the government saw as agreement.

The appellant’s brief argues that without Moore’s requests, the government lacked a way to show quid pro quo, a requirement of bribery charge: that Crisler committed or agreed to commit an official act in exchange for funds.

Moore also asked Crisler to give him bullets despite being a convicted felon, which is prohibited under federal law. The brief notes how the government directed Moore to come up with a story for needing the bullets and to ask Crisler to give them to him.

In response, Crisler told Moore he could buy bullets at several sporting goods stores. Moore said they ran out, and eventually Crisler gave him bullets.

Crisler also argues that the government prosecuted routine political behavior. Specifically, accepting campaign donations is not illegal, and can not constitute bribery unless there is an explicit promise to perform or not perform an official act in exchange for money.

“Our political system relies on interactions between citizens and politicians with requests being made for this or that which is within the power of the elected official to do,” the brief states. “This does not constitute a bribery scheme. It is the normal working of our political system.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post FBI concocted a bribery scheme that wasn’t, ex-interim Hinds sheriff says in appeal appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Right

The article presents the legal appeal of former interim Hinds County sheriff Marshand Crisler with a focus on his argument that the FBI orchestrated an entrapment scheme. The language is largely factual and centers on the defense’s claims and legal standards for bribery, emphasizing normal political behavior versus illegal conduct. While the article reports on the government’s position, it gives significant space to Crisler’s defense and critiques of federal prosecution tactics. This framing, highlighting skepticism toward federal law enforcement and emphasizing the defense perspective, suggests a slight center-right leaning, reflecting a cautious stance on government overreach without overt ideological language.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

Rural Texas uses THC for health and economy

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

Yelp names ‘Top 100 Sandwich Shops’ in the US, several Texas locations make the cut

-

Mississippi Today2 days ago

After 30 years in prison, Mississippi woman dies from cancer she says was preventable

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Harrison County Doctor Sentenced for Unlawful Distribution of Controlled Substances

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed7 days ago

Released messages show Kerrville officials’ flood response

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed7 days ago

Residents along Vermilion River want cops to help prevent land loss

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Decision to unfreeze migrant education money comes too late for some kids

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed6 days ago

‘Half-baked’ USDA relocation irritates members of both parties on Senate Ag panel