Mississippi Today

The death of rural hospitals could leave Mississippians ‘sick, sick, sick’

The death of rural hospitals could leave Mississippians ‘sick, sick, sick’

GREENWOOD – Only a few dozen cars sit in Greenwood Leflore Hospital’s parking lot.

The hospital’s windows, streaked with purple paint, read, “Stay strong!” Another one says, “We love our patients!” Behind the glass, magazines sit untouched on side tables —the lobby is vacant.

Greenwood Leflore is the community’s only hospital, and it’s months away from closing.

The COVID-19 pandemic drained the hospital, which was already financially vulnerable, dry. Costs went up, while profit did not. Doctors and nurses, burned out from the pandemic, left in droves. Now, the hospital is shutting down floor after floor, cutting costs to maintain operations.

Mississippians know this story.

Dozens of hospitals across the state, many the only in their communities, are struggling to stay open.

A report from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform puts a third of Mississippi’s rural hospitals at risk of closure, and half of those at risk of closure within the next few years. There are only three other states with worse prognoses.

But it’s especially devastating in Mississippi, where life expectancy and health outcomes are consistently the worst in the country.

Hospital administrators are holding their breath, waiting on help from the state, but they could be getting less money this year than they need. And there’s little to no chance that state leaders will expand Medicaid this year as 40 other states have done. Expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act would bring more than $1 billion in federal funding to Mississippi in a year.

Ryan Kelly, executive director of the Mississippi Rural Health Association, said the situation is dire, and there’s not a straightforward answer.

“I wish, for the sake of simplicity, I had one single thing I could point to and say this is the problem,” he said. “We have been saying this for a long time that this will get serious and it is now serious.

“We are in far more of a serious time now than we ever have been before.”

For the hospital CEOs, doctors and residents of rural Mississippi, this isn’t just a statistic. It’s a life-and-death reality.

‘Hospitals can close. Watch and see.’

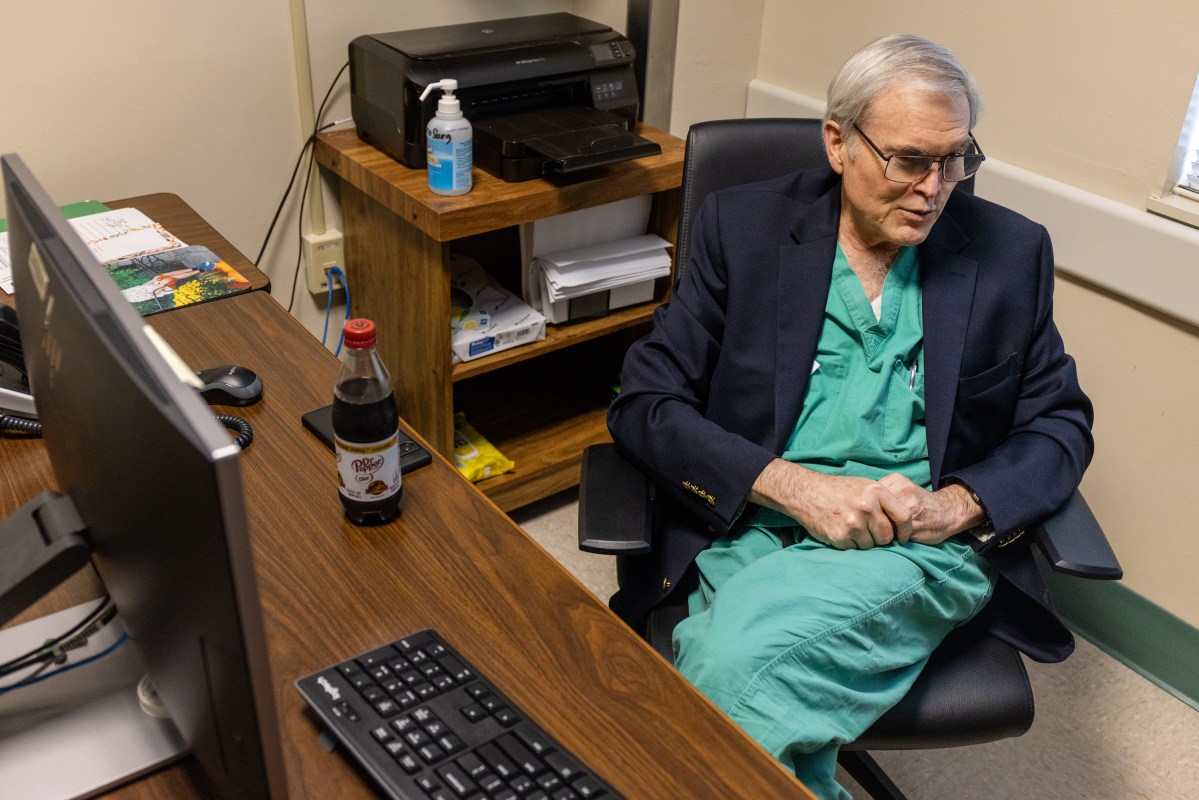

Dr. John Lucas’s office is at the end of a quiet hallway, past empty rooms with empty beds.

Though he’s spent his entire professional life at Greenwood Leflore, Lucas, a longtime Greenwood resident and now chief of staff, remembers starting his career as a surgeon in a much different hospital than the one he sees today.

His late father, Dr. John Lucas Jr., practiced at Greenwood Leflore from 1963 until his retirement in 2011. Back in the hospital’s heyday, Lucas said his father’s patients overflowed into the hallways. At that time, the hospital was licensed for 250 beds, he said.

When Lucas joined his father at the hospital in 1988, he didn’t experience that level of activity, but it was a far cry from the desolate hospital he serves today.

“It wasn’t uncommon to have as close to 200 beds full when I first came here,” he said. “It’s really sad to walk these empty halls and to see that we only have one part of one floor occupied with patients.”

In the past decade, Lucas has watched the hospital close unit after unit, tapering services in an effort to stay open.

First it was the neurosurgery department. Then, it was the urology department and inpatient dialysis. Now, the hospital doesn’t have full coverage of its emergency room for orthopedics or general surgery. Most recently, it shuttered its labor and delivery department and intensive care units.

At a health affairs committee meeting in February, Nelson Weichold, chief financial officer at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, said the worst part about the looming hospital closures is the slow cessation of services.

“It’s not just when the hospital closes,” he said. “It’s the years building up to that when they’re taking financial measures to do everything they can to try and keep the doors open.”

But it’s not financially viable to keep all of those service lines open anymore, according to Greenwood Leflore’s interim CEO Gary Marchand.

About 75% of the hospital’s patients are uninsured or on Medicaid or Medicare, which underpay the hospital for its services, Marchand said.

So most of the time, that means the hospital is losing money caring for its patients. And for the quarter of patients who have commercial insurance, the hospital often has to fight with the company to get the claim paid, he said.

“Our challenge is we have to map the inadequacy of those payments to our cost structure,” Marchand said. “For years, systemically, they (Medicare, Medicaid and commercial insurance) have paid below real cost.”

Before 2020, the hospital was losing between $7 to $9 million a year, Marchand said. To satisfy the city and county, which partially own the hospital, Greenwood Leflore leaders came up with a plan to generate $7 million a year to break even.

Then COVID hit, and everything changed.

The hospital went into the pandemic with $20 million in cash reserves. With each wave of the virus, despite government relief, their reserves were depleted. By the end of 2021, half of the cash was gone.

It’s a fallacy that hospitals made money during the pandemic, Marchand said. Because Medicaid and Medicare paid for patients by their diagnosis, not the length of their hospital stay, patients who were in the ICU for weeks ended up costing the hospital.

Greenwood Leflore hasn’t been able to make the money back — it’s not clear why, but fewer people are seeking care, and payments have remained stagnant.

For several months, the University of Mississippi Medical Center was entertaining a plan to lease the hospital, saving it from closure. However, in November, the deal abruptly fell through without explanation from UMMC.

Marchand said the hospital has six months to figure out a plan or it’ll be forced to close.

“The struggle is to get the community and the legislators and others to understand a hospital is a business,” he said. “I think a lot of people think, ‘Oh, you need hospitals. They’re never going to go away.’

“Hospitals can close. Watch and see.”

A quick scroll on the hospital’s Facebook page shows that Greenwood residents know that closure is a real possibility.

Lucas said he hears the same refrain over and over again when he’s out in the community: “How’s the hospital doing?”

“Whenever I go to a social outing, it’s the first thing I get asked,” Lucas said. “Everybody’s concerned.”

Pie Fincher and her family are products of Greenwood Leflore Hospital.

Fincher, who is 89 years old, has only gone to another hospital for treatment one time in her life. Both of Fincher’s children were born at Greenwood Leflore, and the hospital has saved her life several times, she said, including once when she had a major brain bleed.

“It’s just been a lifeline for our family,” Fincher said.

But the neurology department doesn’t exist anymore. Neither does labor and delivery. Those doctors that delivered her kids and saved her life are long gone.

“I vividly remember how proud we were of that hospital to be built (in its current location in 1952),” Fincher said. “It was just state of the art everything. As time has gone on, we’ve been so fortunate to have so many wonderful doctors.

“That’s what’s so heartbreaking about it, is we have all these wonderful doctors that are willing to work in Greenwood — this little small, nondescript, tiny town — and we let them go.”

DeWitt Kimble was born in Greenwood 72 years ago. In the past few years, because of problems with his prostate, he’s increasingly relied on the hospital for emergency care.

Kimble first heard the hospital might shutter about a decade ago. Now that its closure is imminent, he’s worried.

“If you really close this hospital down, we’re going to have to go to Jackson,” he said. “We’re going to have to go to Grenada. We’re going to have to go to Cleveland, and a lot of people don’t have transportation, like me.”

The motor gave out on Kimble’s Suburban about a month ago, and he’s not been able to afford its repair.

If the hospital closes, residents such as Kimble will be forced to travel a half hour or more for care. In the Delta, where much of the population struggles with reliable transportation, the lack of a nearby hospital could be fatal.

Between a quarter and a third of Lucas’ surgeries are canceled, largely because of transportation issues, he said.

Kimble had a surgery scheduled on Monday to remove his catheter. His primary care physician at a private practice said he’d arrange for Kimble’s transportation, but Kimble said he’s called the office repeatedly, and no one has answered.

No one from his doctor’s office could be reached for comment by press time.

Kimble never made it to his procedure.

“I’m just sitting here, so frustrated,” he told Mississippi Today on Monday afternoon.

That means Kimble will still have to rely on his doctor in Greenwood and the hospital for continuing care.

“If the hospital closes, there will be a lot of walking dead,” he said. “Folks will be sick, sick, sick.”

Marchand’s Plan A is getting Greenwood Leflore designated as a critical access hospital. That means the hospital would have to give up almost all of its 200 beds, but it would get more money for services that it provides. Critical access hospitals are typically reimbursed by Medicare at a rate of 101%, theoretically allowing a 1% profit.

State Health Officer Dr. Dan Edney said closing service lines and applying for different hospital designations are solutions he’s seen increasingly across the state, but especially in the Delta. Though they might keep hospitals open, it’s still a loss for the community, he said.

“You take what was a vibrant hospital in the Delta, pre-pandemic, and now it’s a shell of its former self, post-pandemic,” Edney said. “Their only road to survivability is to downgrade.”

But to qualify for the designation, Greenwood Leflore would have to be 35 miles from the nearest hospital.

They’re just short —South Sunflower County Hospital in Indianola is 28 miles away.

Marchand is hoping for a waiver from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare regarding the distance requirement. His argument is that because of transportation challenges for the hospital’s population, the hospital should be an exception.

If that doesn’t work, the hospital will go up for sale again.

The survival of Delta’s largest health care system will be ‘touch and go’ after this year

If you ask Iris Stacker, interim CEO of Delta Health System in Greenville, how long the hospital system has before it’s forced to close, perplexingly, she smiles.

“I intend to be here forever,” Stacker says.

But Chief Nursing Officer Amy Walker raises an eyebrow.

“We’ll be here through the end of the year,” Walker deadpans. “It’s really touch and go after that.”

The duo head up the largest health care system in the Mississippi Delta. And together, they’re trying to keep it from closing.

Walker’s cynicism is often balanced out by Stacker’s cheeriness, but they do agree on one thing: The hospital is losing money.

“Even Positive Polly over there can’t deny that,” Walker said.

Despite being licensed for over 300 beds, the hospital’s census hovers around 80 patients. And most of the patients are uninsured or on Medicaid or Medicare.

Last year, Delta Health spent about $26 million on uncompensated care. That amounts to about 15% of its total operating expenses.

“We don’t turn people away,” Stacker said. “Instead of trying to go to a doctor and pay for that visit, they wait until 5 p.m. and come to our emergency room.”

But the decline in hospital patients isn’t because care isn’t needed in the Delta, which has some of the worst health disparities in Mississippi.

“It’s not because the patients aren’t here,” Walker said. “It’s because we don’t have the nurses to take care of them.”

Walker said the hospital has long struggled to recruit nurses to Mississippi, much less the Delta.

“We’ve always had that problem,” Walker said. “And if you look at our salaries, we usually have to pay more than Memphis and Jackson to get nurses here. We were already used to doing that.”

The problem worsened during the pandemic, as nurses were offered more money to travel or work elsewhere. Others got so burned out that they went ahead and retired. Statewide, nurse vacancies and turnover rates are at a 10-year high.

Since the pandemic, the hospital’s nurse workforce has nearly halved.

The exodus’ effects have rippled throughout the hospital: emergency wait time has quadrupled, the largest medical surgery unit is closed, and half of the hospital’s ICU beds are not in use.

“You would think that now three years out, things would have normalized, but they haven’t, and I don’t think we’re ever going to get back to normal,” Walker said. “We’ve lost so much of our volume at this point. I can’t really predict if it will come back.”

During the pandemic, supply and labor costs shot up. While prices aren’t as high as they were then, they haven’t returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The way Walker explains it, if the price of eggs goes up, a grocery store can make up for the inflation by passing the cost down to the consumer. But that can’t happen in a hospital setting.

Delta Health has to keep serving its patients, no matter if it’s losing money or not.

“We’re pretty much living on grant money right now,” Stacker said.

Stacker knows that Medicaid expansion is unlikely to pass this legislative session, though it’s what she thinks would help the most.

Without systemic changes, Stacker admits that the hospital’s fate is uncertain.

And if the Delta loses the hospital system, it’s going to affect the entire region.

“We save people’s lives every day here,” Walker said. “Once hospitals start closing, those patients aren’t just going to go away.”

Staying afloat, for now

Winston Medical Center’s CEO Paul Black is a numbers guy.

Black’s hesitant to say it, but he admits that his background has helped keep the hospital afloat.

Before taking the helm of the hospital, Black did consulting work for hospitals around the state and made use of his accounting degree as an auditor for the Medicare program.

“This reimbursement stuff is what I grew up doing,” he said. “So when I got started, I had already been on that side of the fence.”

Something his financial background did not prepare him for, though, was a disaster in his first week of work in April 2014.

Six days into his tenure, Louisville was hit by a devastating EF-4 tornado.

“I don’t remember a whole lot about what took place the first six months,” Black said. “I won’t say that I walked around in a fog, but there was just so much going on. And there’s no manual for it.”

During that time, funding was coming from various sources — disaster relief, cash reserves, community loans —which is why, years later, Black said the hospital’s finances don’t look as dire as many other hospitals in the state.

Winston lost money caring for patients during the pandemic, and Black said expenses have gone up while payments have not increased. The nursing home’s population has also been depleted because so many elderly Winston County residents died during the pandemic.

However, Black fought back with changes of his own.

The hospital raised nurse salaries, which convinced many to stay. Additionally, he’s made sure the hospital offers a diverse array of services —from a nursing home to mental health needs — to protect them from financial collapse.

“That keeps a lot of people coming here,” he said. “We’ve been very efficient with what we’re doing.”

But he warned that Winston Medical Center, while not in the red, isn’t in the green either.

Black’s predecessor, Lee McCall, now heads up Neshoba County General Hospital in Philadelphia, less than an hour from Louisville.

Neshoba County was similarly impacted by COVID —McCall said hospitalizations are down by about half, in part because many of the hospital’s chronically ill and elderly patients who regularly sought care or were in the nursing home died during the pandemic.

When McCall took the CEO job in 2014, the hospital averaged 1,500 annual admissions. Last year, they had 750.

Because of the drop in census, the hospital closed one of its acute floor wings in October to cut costs.

Additionally, more people are visiting the emergency room, where they know the hospital will provide care, whether or not they’re insured.

“Our ER visits have definitely gone up,” said Dr. Jon Boyles, the hospital’s emergency department director. “We’re seeing it seems more and more people who basically use the ER as a clinic.”

The hospital also lost staff during the pandemic — staff they can’t afford to hire back. McCall said he’s trying to do everything he can to prevent layoffs.

“To be honest, there’s just not anywhere to really lay off unless we just shut down a service line completely, which we’re trying to avoid at all costs,” he said.

McCall has kept a close eye on the Capitol the past few months. Like Stacker in Greenville, McCall knows Medicaid expansion isn’t going to happen this session, but he’ll keep advocating for it.

He doesn’t deny that hospitals need the grant money making its way through the Legislature, but said hospitals need a sustainable solution — not a temporary one.

“That’s one-time money,” McCall said. “That doesn’t fix the ongoing problem. So we’re going to be right back where we are now next year.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

This superintendent took a failing Delta school district to a ‘B’ rating. Now, she’s leaving

INDIANOLA — The top of the Jeep was down, and Miskia Davis was behind the wheel, leading a parade through downtown Indianola.

It was 2019, just two years after the now 50-year-old Davis became superintendent of Sunflower County Consolidated School District. Back then, she wasn’t sure this moment would ever come.

She recalled feeling the first cool breeze of October as she waved at people who lined the street, smiling and celebrating.

But it had — the district’s first “C” rating, its first passing grade, and the community had shown up to a parade to celebrate the achievement. Generations of teachers and Sunflower County graduates stood on the sidewalk, proudly cheering the assembly of cars and students.

“It was … Oh my God,” Davis said. “My children were like, ‘We did something.’”

The work hadn’t been easy, but it had been worth it, Davis thought — the number crunching, the doubt and lukewarm welcome she felt from the community, the tough decisions she’d had to make.

Now, she’s ready to move on.

Daughter of the Delta

From starting kindergarten to subbing for elementary classes, Davis’ childhood and career in Sunflower County and her identity as a daughter of the Delta were her strengths in the classroom, she said.

“I grew up in Drew, poor and with two young parents,” Davis said. “We didn’t have elaborate meals, and when I went home, the lights may have been off. But it made me who I am, and these children were experiencing the same things I experienced as a child.”

So Davis was relatable. But as a young high school teacher at Ruleville Central High School, some of her students looked older than her and many were taller than she was. She was forced to learn how to command respect, too.

One particular child taught her an invaluable lesson. He was a star football player in her biology class, and he was failing the course by two points. He caused trouble in class and Davis was determined to fail him, despite more experienced teachers prodding her not to, to look past her own ego.

So Davis gave him another chance. She had him do extra work and spent hours talking to him. She learned why he behaved poorly in class — he was one of seven children to a young, single mother.

“He was angry at the world, and I just happened to be in the world,” she said. “It taught me the power of relationships. I think that’s the most important catalyst in transforming education.”

It was during that time that her superintendent “saw something” in her and pushed her to become a school leader. That kickstarted her journey in administration.

Davis soon learned she had a particular gift for turning failing schools around. Under her leadership as principal, Ruleville Middle School went from failing to an “A” letter grade in three years.

Her school improvement strategy began to take shape, similar to her teaching style. Davis was both a disciplinarian and someone to whom teachers and students could relate. She prioritized building strong relationships with teachers who were invested in their students. But she didn’t shy away from making controversial decisions, either. In Ruleville, she fired nearly all of the staff when she arrived.

But as Davis was gaining her footing as an administrator, Sunflower County School District was struggling.

After consistent failing grades resulted in the state takeovers of Indianola, Sunflower and Drew school districts, the Legislature decided to consolidate the three systems in 2012.

District consolidation is a massive undertaking for any community, but especially for Sunflower County — smack dab in the middle of the Delta, an under-resourced region with a shrinking population, high poverty rates and a deep history of racial exploitation.

Davis arrived in 2014 to a school district that had lost hope — a district that she didn’t recognize.

All Sunflower knew was ‘failure’

Davis never wanted to be superintendent.

She spent three years working under the leader of the consolidated district. But when the superintendent was dismissed in 2017, Davis was appointed to the head role in an interim capacity. She got the job in January of 2018 without ever applying.

So with another state takeover looming, Davis went to work. The biggest challenge? The district and the community seemed resigned to failure.

“We had been failing so long, that’s all we knew,” she said. “No one was even sad.”

Early on, Davis visited a school to discuss recent test results. She was so struck by teachers’ apathy that she stopped the meeting midway and had them tear off a scrap of paper and write “yes” or “no” to a question: Did the teachers believe their school could ever be successful?

More than half said no.

“They were teaching my children,” Davis said, tearing up. “And they didn’t think they would ever be successful.”

Davis went to the school board to tell members that she wouldn’t be renewing many of those teachers’ contracts. That’s when she realized she didn’t just need to boost test scores — she needed to change attitudes.

The hashtag #WINNING was born.

“We started to celebrate every little accomplishment,” Davis said. “We got T-shirts, shades, whatever. That was our mantra.”

Children received certificates for a week of perfect attendance. When students did well on benchmark assessments, teachers were ushered into the hallway to be celebrated by students and colleagues. Davis created the “Killin’ It” awards, given to students and teachers for meeting their testing benchmarks.

They were just certificates, at the end of the day. But it led to a changed school culture, a renewed belief that they could succeed.

As an administrator, Davis leaned on what she knew worked as a teacher, relationship-building and strong discipline (she even sent her nephew to alternative school for fighting), and combined it with a data-driven approach and an eagle-eyed focus on testing.

She put an academic coach in every building, whose sole responsibility was supporting teachers.

Davis took teacher Dylan Jones out of the classroom and put him in the central office, where he was tasked with tracking district metrics.

Jones uncovered which consultants were working and which were uselessly costing the district millions. The district went from contracting with 30 firms to just four.

Jones also created an accountability system for teachers. With one click, Davis could see how each teacher’s students were performing, and she gave everyone access to the data. If teachers weren’t meeting their goals, Davis hosted regular meetings and had them explain — in front of everyone — what they needed to succeed.

Davis’ methods weren’t popular at first. Educators went to the school board and complained that the system was “punitive.” Some even quit. But Davis was steadfast and implored board members to see the work she and her team could do, if given the chance.

The district’s rating didn’t budge in 2018.

But in fall 2019, after Davis’ first full year as superintendent, Sunflower County Consolidated School District had earned its first “C” rating.

What happened after the first ‘C’

Those early years were difficult, Davis remembered, because she felt so isolated, just her and her team “in the trenches.”

She hosted community meetings, imploring local parents, leaders and business owners to support the district.

“They told me to come back when we were no longer failing,” Davis said.

So after that first “C,” when she started seeing the district’s hashtags on Facebook, when more people started coming to school events, when she started to get invited to speak at the local Rotary Club, it was bittersweet.

Teachers, too, took a while to come around. Their performance was being closely monitored through the accountability system, but soon they realized that Davis wasn’t giving them mandates outside of improving test scores. She gave them autonomy in their classrooms. Teachers had the final say on how to improve their students’ achievement. That kind of trust isn’t common, Sunflower County teachers told Mississippi Today.

It wasn’t until 2021, when voters passed a $31 million bond issue that would pay for major school renovations, that Davis felt the full support of the community.

Davis even won over Betty Petty, a local matriarch and fierce advocate for kids and parents.

“She has actually shown a presence at the schools, constantly meeting with teachers and making sure all children are learning,” Petty said. “We had community meetings where she would actually come out and listen to our concerns.”

Petty attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony at Gentry High School last July. Before renovations, plumbing problems caused flooding when it rained, so students had to wade through water to get from class to class. Davis said she’d never forget the sight of generations of Gentry graduates in the school atrium, looking around in wonder at the new facility.

“At first, I chose the community,” Davis said. “But eventually, the community chose me.”

The legacy she leaves behind

Strong schools make strong communities, but it can take time for results to show. Indianola Mayor Ken Featherstone hopes to see the dividends soon.

Featherstone took office four years ago, around the same time the district got its first “B” grade. It has maintained the grade ever since, the highest in the entire region.

He, like Davis, was reared in the Delta, but empathizes with her struggle garnering the support of a community deeply impacted by gun violence and low investment from state officials.

“People are very result-oriented,” he said, leaning back at his desk in city hall. “You till the soil, but it’s not until you start your seed breaking the ground do you see other people starting to water it. That’s just human nature.”

He’s hoping the district’s academic gains will be a boon for Indianola’s struggling economy.

“We’re seeing things slowly come to our area,” Featherstone said. “To get manufacturing jobs to come to our area, we have to improve our public school system. Directors and presidents of manufacturing plants … they need to know where their kids are going to attend school.”

Davis announced in October 2024 that she would be leaving the superintendent job at the end of the school year. Now, she travels the state, consulting with other districts on how to replicate what she did in Indianola, as a director of District and School Performance and Accountability for The Kirkland Group, an education consulting firm based in Ridgeland.

Her departure was a tough blow, Featherstone said, and leaves the district’s hard-fought success hanging in balance.

Petty and her network of parents are concerned, too.

“I don’t think any of us know what will happen moving forward,” she said.

Davis said there was no big epiphany. She just felt her mission was accomplished. She said she’s adamant that the district’s “best days are ahead,” under new superintendent James Johnson-Waldington.

Johnson-Waldington, who was most recently serving as superintendent of Greenwood Leflore Consolidated School District, is also Sunflower-grown, and he was Davis’ principal when she taught at Ruleville Central High School. He plans on employing strategies similar to Davis: holding teachers accountable and celebrating their achievements.

After all, if it’s working, why change it?

“I feel a good kind of pressure,” Johnson-Waldington said. “I like challenges, and this is a new challenge for me. I’m not taking a failing school district to success. This is about maintaining and growing, and I accept that challenge for the very reason that this is home. I’m going to work very hard to maintain what Miskia has done.”

Davis leaves behind a legacy, Featherstone said, that makes her hometown proud. He was in the crowd that day at the parade. He remembers the excitement, the pride.

“Older teachers were there, and you could see the look on their faces that they knew they had reared someone who threw the oar out to a sinking district and brought it back up,” he said.

“She made us see ourselves in a better light, and we can’t thank her enough.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post This superintendent took a failing Delta school district to a ‘B’ rating. Now, she’s leaving appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a positive and detailed profile of an educational leader working to improve a struggling school district in a historically under-resourced and economically challenged region. The focus on community uplift, education reform, accountability, and addressing systemic challenges aligns with themes often emphasized by center-left perspectives. However, the article maintains a largely neutral and factual tone without overt political framing or partisan language, emphasizing pragmatic solutions and community collaboration rather than ideological positions.

Mississippi Today

Theology student’s ‘brain drains back home’ despite economics, safety concerns

Editor’s note: This Mississippi Today Ideas essay is published as part of our Brain Drain project, which seeks answers to why Mississippians move out of state. To read more about the project, click here.

Though I imagine I’ll never return, more often than not, my brain drains back to Mississippi. My whole adult life has been a journey up and down the Hudson River, from New York City to the Adirondacks, but inevitably, I find my thoughts leaking toward another river.

I grew up fearing being left behind in the Rapture, but in earnest, it feels like I’m the one who left everyone behind. I’m not proud of this, but I’m certainly not ashamed. I have roots in the Northeast now, and a life that isn’t easily transplanted elsewhere, especially to the Red Clay Hills of Neshoba County. Life took me from Mississippi, and life keeps me away.

I left Mississippi for New York in 2015, and I estimate that I’ve returned only 11 times. My sporadic trips home have been mostly because I’m consistently broke, but now it’s a combination of that and concerns for my safety.

My mother, also limited by finances and Mississippi’s minimum wage, has visited me twice in 10 years, once in the spring of 2016 and then when I graduated from Yale Divinity School in 2023.

I haven’t been back since I came out as a trans woman and began medically transitioning in the winter of 2024. I try not to be overwhelmed with guilt or grief for the imagined, shared life I don’t experience with my mother. Rather, I’ve learned to cherish what we do have.

It’s strange to be who I am, mostly for her but also for me. She has learned to love me regardless of whether or not she understands what I’m doing. In her mind, if you go to college, you become a nurse or a lawyer. You settle down, probably in Jackson, maybe Oxford, most likely in my hometown of Philadelphia, and commute by car more than an hour to work. You probably see your mom weekly. She sees her grandkids as often as possible.

That is not how life turned out. We do talk on the phone. Sometimes we get into once-a-week phone call sprees, other times, I drop off for weeks, maybe a month, when I’m depressed.

When I come home, she picks me up from the airport and drives me back a few weeks later. We crack the windows, smoke cheap Mississippi cigarettes and try to cram 10 years of a strange-to-us mother-daughter relationship into a 90-minute ride to the airport in Jackson. Usually, we talk about suffering, death, sin, God, the end of the world, and what the hell I am doing with my life.

You go to college to get a job, to make more money than your parents and to buy a strange suburban-but-rural McMansion just beyond city limits where you start a family around the age of 25 at the latest.

According to my mother, I went to the University of Mississippi and got brainwashed. She tells me often that it’s like she doesn’t know who I am, and she’s mostly right. She hasn’t met anyone I’ve dated in person since high school. She hasn’t seen me in person since transitioning, and I changed my name to Romy. I explain my relationship with my family to friends, peers, new partners and congregations, always with an articulate sense of heartbreak that I’ve learned to intellectualize and package up in a story of “working-class origins,” single motherhood, a white Christian nationalist rural community and my stumbling through adulthood “refusing not to live by my values.”

I originally left Mississippi to be an AmeriCorps Vista volunteer in the Capital Region of New York. I’d never been there. I took a Greyhound from Memphis to New York City to Albany, New York with two large suitcases and a backpack. Several of my friends from college had moved to New York City, and their couches and shared beds provided a safe launching pad for more of us. I had also fallen in love with a fashion student turned designer that I met on a trip to the city the year prior. Though that romance flamed and flickered for many years and ultimately flamed out, my reason for staying in the North was the life I was increasingly stumbling into.

I went there because, at the time, I had an insatiable desire to live out my values and politics. After all, I was maybe one of two socialist public policy majors at the Trent Lott Leadership Institute at the University of Mississippi, and I didn’t want to be a lawyer, a lobbyist or a policy wonk.

I wanted to be poor and engage in building sustainable autonomous communities. I wanted to learn how to be a person who had no work/life distinction, but a vocation and calling.

Through AmeriCorps, I luckily found a small group of activists, urban homestead types, organizers and ex-social workers living together helping others at the margins and themselves start businesses and worker-cooperatives while struggling through mental health crises, and taking on an impossible but seemingly always plausible dream of a directly democratic community owned, operated and governed only by those who live there.

This was my first “job” out of college. It was my dream come true, and the most difficult thing I’d ever done. I burnt out pretty hard after two years, and probably made somewhere between $25,000 and $30,000 during that whole time. Since then, the most I’ve made in a year is my current PhD stipend of about $34,000.

I was, however, helped along by friends, colleagues and the activist communities that I was stumbling into. Through them, I was encouraged to go to Union Theological Seminary, land a job at a prestigious artist residency in the mountains, go to Yale Divinity School, discern that I was called to be a priest and come to know myself as a trans woman.

My life outside of Mississippi has been sustained solely by relationships that transgress the boundaries between work and life, co-workers and friends. I regularly reflect on and often worry about how fragile this all is, and if my own vocational and intellectual pursuits have been worth what I’ve left behind or never had.

I’m not sure I’ll ever know. However, I’ve managed to find profound meaning in it all so far, and it keeps me digging myself into this hole in which I will hopefully find what I am looking for, or dig my own damn grave.

Originally from Philadelphia, Romy Felder (she/her) is currently a PhD student at Union Theological Seminary. She is also pursuing the priesthood in the Episcopal Diocese of New York. She has a background in worker-cooperative development, community organizing, popular education and arts management. Romy lives cavalierly but contentedly in Brooklyn, New York.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Theology student's 'brain drains back home' despite economics, safety concerns appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Left-Leaning

This essay reflects a distinctly personal and ideological perspective rather than neutral reporting. The author frames Mississippi as economically limiting and socially unsafe, particularly for marginalized identities such as transgender individuals, while presenting Northern activist and academic communities in a sympathetic and aspirational light. References to socialism, worker-cooperatives, and critiques of conservative Mississippi culture suggest a worldview aligned with progressive or left-leaning politics. The tone is introspective and critical of traditional Southern expectations, while valorizing alternative, activist-driven lifestyles. As such, the piece is less about balanced reporting and more an expression of lived experience through a progressive lens.

Mississippi Today

‘Get a life,’ Sen. Roger Wicker says of constituents

A note from Adam Ganucheau: A couple hours after this column published, Sen. Roger Wicker’s office reached out and demanded a correction, saying the senator’s “get a life” comment was directed to himself and not to constituents. That’s certainly not how I nor hundreds of Mississippians who commented on and shared the viral video heard it. Mississippi Today has updated portions of this column to reflect concerns raised by Wicker’s office. Here’s a link to the video/audio of his response to the question about constituent concerns. Mississippians can decide for themselves what Wicker meant.

When 34-year-old Thad Cochran arrived in Washington after his first election in 1972, the Republican felt it important to document what he’d heard and learned from Mississippians on the campaign trail and share it with his young staff.

He sat down at a typewriter and wrote a memo titled “General Responsiveness” and dated March 14, 1973:

During the campaign I detected a very strong animosity among the people toward government and those associated with government bureaus and agencies. This included elected officials and those associated with them. Part of the cause of this attitude was due to a lack of feeling or understanding by government people for the needs and opinions of the average citizen. We are all in a job to represent all our constituents. We are not the bureaucracy. A constituent who asks us for help should be assured to be in need of help with our office as his last resort. A constituent who writes a letter should be made to feel by our response that he is glad he wrote us. A constituent who claims to have been wronged by the government should be assumed to be correct. Everyone should guard against developing the attitude that we are better than, smarter than or more important than any constituent. We do not hold a position of authority over any constituent. We are truly servants of the people who selected us for this job.

Every year from 1973 through 2018, over his three U.S. House terms and six U.S. Senate terms, Cochran shared that memo with every staffer who worked in his offices. The guidance, he said all those years, was a necessary reminder to show respect to the people who offer feedback or need help. He never wanted his staff or himself to forget who sent them to Washington.

The memo, like so many other things, serves as a stark reminder that Cochran was among the last in a bygone era of American politics. The perspective he wrote and shared is a far cry from what Mississippians have been getting recently from our current U.S. senators.

“Surely everybody else has better things to do with their time,” senior U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker said to a room full of constituents earlier this month when asked about calls and emails his office has been getting. After half-heartedly explaining that he does see a list of names of people who reach out to his office, he quipped: “Get a life.”

Wicker’s office said Friday that the senator directed “Get a life” to himself, not to constituents.

Wicker, who typically chooses his words a little more carefully, perhaps has been trying to match his junior colleague’s energy.

“Why is everyone’s head exploding?” U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith said in April to Mississippi constituents who had expressed concerns over slashing federal Medicaid spending. “I can’t understand why everyone’s head is exploding.”

There are many kind staffers working for Republicans Wicker and Hyde-Smith who are helpful to Mississippi constituents in any number of ways privately or behind the scenes. These people care deeply about serving their home state and they do it well, and they cannot help how their bosses address the public. But, boy, their phones must be blowing up more than ever since the senators made these comments.

Consider, for a moment, what it means that we have devolved from having a leader who believed that “a constituent who claims to have been wronged by the government should be assumed to be correct” to one who thinks telling constituents to “get a life” is appropriate. Think about the fact that we replaced a leader who regularly reminded his staff that “we are truly servants of the people who selected us for this job” with one whose gut response to legitimate concerns from constituents is that their “heads are exploding.”

Just … wow. To call it alarming doesn’t fully encapsulate the gravity of their behavior. It’s enough to discourage even the most optimistic among us about the present and future of our state and our nation.

It’s enough to inspire you to ponder, in this intense political climate when unprecedented and harrowing federal government decisions are being made and going largely unchecked every day, whether our current U.S. senators even remember why they’re in Washington, why we sent them there.

It is necessary, in the shortest possible order, to ask and answer for ourselves what we should expect of our elected officials and whether we should feel OK about being dismissed or ignored outright like this.

You don’t have to be a Democrat to think that this behavior is out of line. Plenty of Republicans — some publicly and many privately — are increasingly disturbed by what’s happening in Washington. Regardless of your own personal political beliefs, be honest with yourself about whether you can read these comments from our senators and still feel that your best interests are being represented.

Sadly, we can no longer ask Cochran to help us answer these questions, but it sure seems clear where he’d stand. What about you?

READ MORE: Mississippi, where ‘We Dissent’ means nothing to elected officials

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'Get a life,' Sen. Roger Wicker says of constituents appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content critiques Republican senators for their dismissive attitude toward constituents, contrasting them with a more respectful past leader. It highlights concerns about current political behavior and governance, emphasizing accountability and responsiveness to the public. While it acknowledges that some Republicans privately share these concerns, the tone and framing suggest a leaning that favors more progressive or reform-minded perspectives, typical of center-left commentary.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

Kratom poisoning calls climb in Texas

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed3 days ago

New Texas laws go into effect as school year starts

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed5 days ago

GRAPHIC VIDEO WARNING: Man shot several times at point-blank range outside Memphis convenience store

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed3 days ago

Floridians lose tens of millions to romance scams

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

Unsealed warrant reveals IRS claims of millions in unreported sales at Central Kentucky restaurants

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

‘Get a life,’ Sen. Roger Wicker says of constituents

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Woman charged in 2024 drowning death of Logan County toddler appears in court

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Leavenworth mother found guilty in death of 1-year-old daughter