Mississippi Today

Behind First Lady Reeves’ "Fred the Turtle" is a little-known religious welfare initiative slowly receiving state funding

Behind First Lady Reeves’ “Fred the Turtle” is a little-known religious welfare initiative slowly receiving state funding

Last year, Mississippi First Lady Elee Reeves announced the launch of her new initiative aimed at improving child development – an issue leaders have increasingly recognized as a critical economic driver in the most impoverished state in the nation.

Joined by the press in the Governor’s Mansion, Reeves revealed her new strategy: She wrote a children’s activity book about a turtle named Fred.

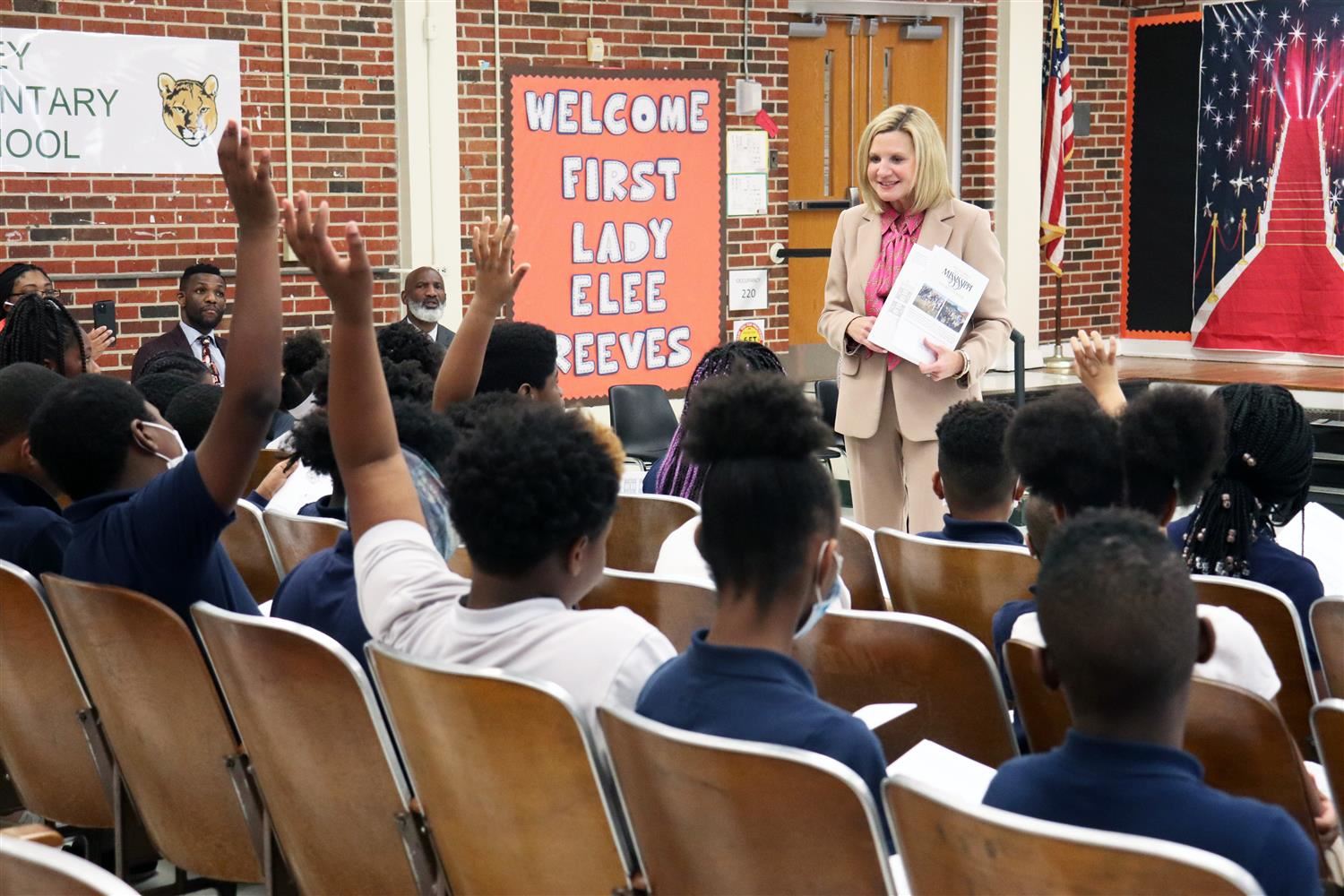

Throughout February and into March, about nine months before her husband’s reelection bid, Reeves began traveling the state, garnering media attention as she passed out copies of the book.

Reeves hopes that Fred, named after her childhood imaginary friend, and the story of his journey through Mississippi “will help our children to develop the lifelong skills that they need to become successful adults,” she told TV reporters at the March 2022 press conference.

Reeves’ book — 20 pages of stapled white cardstock featuring comic sans font and a green cartoon turtle on the cover — may have taken center stage at last year’s event, but side remarks signal something far more consequential is brewing.

At the announcement, Reeves was flanked by individuals representing Casey Family Programs, a national foster care foundation credited with funding production of the book, and The Hope Science Institute of Mississippi, a little-known nonprofit that quietly evolved from a child welfare initiative called Family First.

The new nonprofit oversees an initiative called Programs of Hope, which consists of an advisory council chaired by Reeves and Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Dawn Beam.

Financial documentation is not yet available for 2022, so it’s difficult to see where The Hope Science Institute, also known as Hope Rising Mississippi, is receiving its funding, how much it’s receiving, or where it’s going. Officials said a grant from Casey paid to print the initial copies of Reeves’ book, called Fred the Turtle. While the two organizations would not disclose the size of the grant, the governor’s office told Mississippi Today that Casey Family Programs awarded Hope Rising $28,500 to print 33,000 books.

But Mississippi Today also uncovered that Hope Rising quietly paid to print thousands of additional copies of Fred the Turtle with $10,000 in federal Head Start funds appropriated to it by the governor’s office.

A spokesperson in the governor’s office justified the expense by describing the coloring books as “materials to promote better linkages between Head Start Agencies.” This goal is not advertised in PR and news alerts about the book. Pressed further, the spokesperson clarified the books Hope Rising paid to print last year will be distributed to Head Start classrooms starting this May.

“Almost since the beginning of our governor’s administration, we were looking for ways to build hope, and the First Lady and Justice Beam have been working together on Mississippi Programs of Hope in the effort to bring together government, the private sector and nonprofits to work together,” Cindy Cheeks, director of program operations for The Hope Science Institute, said at the 2022 book announcement.

The First Lady of Mississippi, Elee Reeves, visited Dixie Attendance Center today to present 4th graders a copy of her new book, “Mississippi’s Fred the Turtle.” The book follows Fred the Turtle on his journey around Mississippi and some of its most historic places and landmarks. pic.twitter.com/KPsNJT0Q4V

— Forrest Co Schools (@ForrestCounty) February 24, 2023

The concept bears striking resemblance to the Family First Initiative, for which Cheeks formerly served as a strategic initiatives coordinator. But onlookers wouldn’t know from press releases or promotional materials how one initiative grew from another.

Family First was a short-lived judicial initiative launched by Beam and former Mississippi First Lady Deborah Bryant in 2018. Former Gov. Phil Bryant and others advertised Family First as the catalyst for a significant overhaul of Mississippi’s child welfare system.

The idea was to prevent child neglect by connecting needy families to resources in their community — food, clothing, beds, money for rent or power bills, transportation, job training, etc. — so that the state didn’t have to remove children from their homes.

Instead, the state sold empty promises through the initiative, Mississippi Today found in its 2022 investigation, and while the members say some meaningful work did occur on the local level, the project’s demise was one of many casualties felt by a larger welfare scandal that broke in 2020.

“They were lying,” Beam recently told Mississippi Today, referring to the Bryant administration’s promise to create a database that could connect families to resources and track needs and outcomes.

While two separate and distinct entities, there was a close association between the Family First Initiative and Families First for Mississippi, the now defunct welfare program run in part Nancy New, who pleaded guilty to fraud and bribery.

The New nonprofit program, also promoted by former Gov. Bryant, served as a vehicle for officials, including former welfare director John Davis, to misspend tens of millions of federal grant funds from the Mississippi Department of Human Services. Beyond sharing a similar name and goal, Family First and Families First were entangled with many of the same characters. They even had the same logo, the result of a bungled branding campaign carried out a PR firm called Cirlot Agency.

After agents from the auditor’s office arrested New and Davis in 2020, Families First for Mississippi immediately shuttered and the court-affiliated Family First Initiative vanished.

“I can tell you that at some point, I was bluer than blue about all this. It broke my heart,” Beam told Mississippi Today in 2022, referring to the welfare scandal.

Beam — daughter of former Mississippi Baptist Convention president and preacher Gene Henderson and sister to Pinelake Baptist Church pastor Chip Henderson — then quoted a Bible verse: “Don’t grow weary in doing good.”

“We can’t quit trying to find resources to help our kids. If anything, we have to fight all the harder,” she said. (Beam spoke to Mississippi Today in an individual capacity, not as a representative of the court.)

Since then, architects of the judicial initiative have tried to rebrand and distance their mission from the corrupt welfare delivery system and its leaders. The new initiative no longer proclaims goals as lofty as reducing the foster care population; it’s more focused on “sharing the power of Hope.”

And while Elee Reeves promotes building resilience in children, her husband squeezes the state of the resources it could use to stabilize households and satisfy that goal.

Gov. Tate Reeves has left millions of federal welfare funds unspent. He sent $130 million in rental assistance back to the federal government. And he continues to adamantly reject billions in Medicaid funds that could provide health insurance to poor parents.

Shortly after arrests in the sprawling welfare scandal, Beam began a new court effort similar to Family First called “Programs of HOPE” under the Mississippi Supreme Court’s Commission on Children’s Justice. HOPE stands for housing and transportation; opportunities for treatment; parent and family support; and economic opportunities — though the program does not itself provide or fund these services.

Former Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Jess Dickinson — who headed the state agency that oversees foster care during the Family First era and previously had to recuse himself as the judge in Davis’ criminal case — assisted with HOPE’s creation, narrating and uploading an informational video about the program.

Beam was inspired by the book “Hope Rising” by Casey Gwinn, an attorney and founder of a violence prevention organization, and Chan Hellman, a social work professor at the University of Oklahoma.

The book provides an alternative perspective to the heavily-cited, widely-accepted Adverse Childhood Events or ACE score.

The ACE score is a framework developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control for understanding the correlation between childhood stressors and adult health outcomes — and the corresponding resiliency test, which measures the exception to the rule. In other words, the more traumatic childhood events a person experiences, the higher risk they are for chronic health problems and other challenges in adulthood, unless they have high resiliency.

This goes hand-in-hand with the idea of “trauma-informed care,” which promotes a holistic approach to addressing challenges, recognizing the role that trauma plays in a person’s life.

“Hope science” presents the theory that a person’s level of hope – “the belief that your future can be brighter and better than your past and that you actually have a role to play in making it better,” according to the book – is the greatest indicator of future success.

Beam was struck by the concept.

“Many of us (judges) have been doing this for years. We just didn’t have what to call it,” Beam told Mississippi Today in 2022. “Talking to people in such a way instead of screaming and yelling at them about getting off your butt and finding a house and a job so you can get your kids back, and rather saying, ‘How can I help you? We want your children to be with you because we know that’s going to be the best thing,’” Beam said.

Beam then helped set up a private nonprofit called The Hope Science Institute of Mississippi, and moved the public court function of “Programs of Hope” under the private organization in 2021. The organization changed its operating name to Hope Rising Mississippi in 2022.

“Programs of Hope simply helps them (state and community leaders) to connect and facilitate the exchange of ideas,” Beam recently told Mississippi Today. “It’s exciting to see how light bulbs start going off, where agencies thought, ‘We could never get this done.’ And then all of a sudden, vouchers are there, or transportation is there, those types of things. Parenting – we’ve never had any standard for parenting classes and now that’s coming about. It’s just that opportunity to bring people together.”

The program has received virtually no media attention, save for a feature in Mississippi Christian Living magazine. The article described Hope Rising as a “new nonprofit that aims to create lasting, systemic change in Mississippi through the science of hope (which, yes, is a real thing).”

According to a press release, Justice Beam was supposed to represent Programs of Hope at Elee Reeves’ 2022 book announcement, but her former assistant Cheeks spoke instead. Cheeks explained that Fred the Turtle was born out of the efforts of Programs of Hope.

Cheeks, who worked as a coordinator for Family First during her employment at the Mississippi Supreme Court, is also a longtime administrator for an organization called GenerousChurch, which works to “train Biblical generosity.”

While Beam serves as an advisor to the nonprofit and chairs one of the nonprofit’s programs, the judge is quick to clarify that she is not an employee or a board member for the nonprofit.

The director of Hope Rising Mississippi is Amanda Fontaine, who also serves as director of the Mississippi Association of Broadcasters. Fontaine previously worked for New’s program Families First for Mississippi, according to past articles describing Fontaine as the program’s “director of development and sustainability.”

A 2018-2019 ledger of Families First expenses from New’s nonprofit — which the State Auditor found contained errors — does not reflect that Fontaine was on payroll, but it did list $1,500 worth of reimbursements to Fontaine for food and travel.

“I’m in another role helping numerous people,” Fontaine told the Jackson Free Press in a 2018 feature about her work. “(Families First is) about … the family as a whole. They have so many programs that help families and children.”

(A week before the story ran, New’s nonprofit paid Jackson Free Press $400 for a quarter-page ad with the memo “Congrats to Amanda Fontaine,” according to the ledger).

Hope Rising’s publicly listed address is Fontaine’s residence in Brandon.

Its board president is Jeff Rimes, whose law partner Andy Taggart was on the state steering committee of the original Family First Initiative.

For Rimes, the familiar characters between the old and new welfare initiatives doesn’t come as a surprise. “I often say Mississippi is ‘one big small town.’ Some overlap is inevitable in the world of nonprofits and government,” Rimes said in an email.

Another team member and co-founder of Hope Rising is former FBI agent Christopher Freeze, who served a stint as the director of the embattled Mississippi Department of Human Services under Bryant. Bryant appointed Freeze to replace Davis in August of 2019 after Davis was ousted for fraud.

After leaving the agency as Bryant’s term was ending in early 2020, Freeze dove into the field of trauma-informed leadership and began studying for his doctorate in philosophy in organizational and community leadership. He started motivational speaking and formed an LLC for his services called Mr. Freeze Enterprises.

“I know that a lot of you have programs and services,” Freeze said to social workers and service providers in a keynote address at Hope Rising’s inaugural event, MS Hope Summit, just days after Elee Reeves’ 2022 press conference. “I know that you think that you’re involved in programs and services and that that’s the goal. Let me just tell you, that is not the goal. Your programs are pathways to those goals. Your job is to help that person understand what their goal is and how your programs can help them achieve their goal. And then help them maintain, motivate their willpower.”

Mississippi Child Protection Services Director Andrea Sanders, who oversees the state’s child welfare and foster care system, and many state employees attended last year’s summit. Tickets to the event were $25 and the organization also solicited event sponsorships from $500 to $10,000.

A couple months later, the Governor’s Office gave Hope Science Institute $10,000 in funds from Head Start, the federal preschool program for low-income families. All of the money was used to print 7,500 copies of Elee Reeves’ Fred the Turtle book, according to records Mississippi Today obtained.

“It was a one-time expense of the Head Start Collaboration Office for printing services for materials to promote better linkages between Head Start Agencies, other child and family agencies, and to carry out the activities of the State Director of Head Start Collaboration,” Shelby Wilcher, spokesperson for the governor, said in an email last year.

Head Start does not appear as one of the agency partners listed at the end of Fred the Turtle, nor does Hope Rising appear to do work with Head Start centers.

Asked for more clarification, Wilcher said in a statement that after Fred the Turtle was “so well received by students,” Casey Family Programs awarded a second grant to offer books for students in all of Mississippi’s 82 counties. After the second Casey grant, “the decision was made to expand the initiative to kids in Head Start,” though nearly a year after first ordering the books to be printed, they have not yet been delivered.

“Once the books funded through the Casey Foundation have been distributed, Fred the Turtle will crawl into Head Start classrooms,” Wilcher wrote.

The aim of the Hope Rising, which has already started delivering lectures to government workers about the science of hope, revolves not around providing evidence-based services to low-income families, but promoting the concept that “hope” is a tangible quality that can be taught, measured and utilized to overcome trauma and generational poverty. This year’s annual “Hope Summit” is set for April.

Hope Rising advertises a summer camp called Camp HOPE America, a national program with which the nonprofit is “working to secure its affiliation status,” and a year-long program called Pathways, which is operated by existing local community organizations, according to its website.

Hope Rising also takes some credit for the state offering five new housing vouchers to young adults aging out of foster care — a program called the Foster Youth to Independence (FYI) Voucher program that the long-standing Tennessee Valley Regional Housing Authority applied to the federal government to start receiving.

“A wide variety of organizations within the state worked for months to forge a process for leading FYI vouchers and determine the supports necessary to assist these youth in transitioning to independence,” a Hope Rising press release says.

It also promotes an initiative called “365 days of prayer.”

Hope Rising was initially incorporated as Hope Science Institute of Mississippi by Madison pastor Dan Hall. At that time, the organization’s website described its mission as “changing the trajectory of our most at-risk youths” and outlined its four action areas: “pray, preach, practice and partner.”

“Can you imagine the impact the Body of Christ could make as we all come together to strengthen families and serve on another at one time?” the old website read. “We are looking at April being a month of hope in action across the state through the Body of Christ, organized with purposeful impact in your own community.”

Cheeks told Mississippi Today in 2022 that Hope Science Institute of Mississippi operates mainly on grants from Casey Family Programs and other private funding. She said that money goes towards administrative salaries, planning and meetings. The organization itself does not provide any direct child welfare services.

Rimes said the majority of time put in by nonprofit staff has been unpaid. “I have been deeply impressed and am extremely appreciative of the servants heart they have displayed,” he wrote.

Rimes did not answer questions from Mississippi Today about how much money Hope Rising gets from Casey Family Programs. Casey Family Programs also would not answer questions about its partnership with Hope Rising.

“Hope Rising has a diverse board of professionals from across our State who are focused on ensuring hope is brought to Mississippi in the best possible way. Financial integrity will always be a focus of our board,” Rimes said in an email.

In 2021, the nonprofit had revenue of $8,000 and spent $3,800, all on administrative expenses, according to the Mississippi Secretary of State’s Office. Information for 2022 is not yet listed. Hope Rising’s IRS reports, called 990s, are not available online. Rimes provided Mississippi Today a 990 filing from the nonprofit for 2021 that did not contain any financial data. The 2022 filing is not due until May.

Mississippi Today reviewed state expenditures to The Hope Science Institute of Mississippi in the state’s public-facing accounting database. In fiscal year 2022, Hope Science Institute of Mississippi received $2,525 from the Mississippi Department of Education for employee training, $1,300 from the Mississippi Department of Human Services, $3,000 from the Department of Mental Health and $10,000 from the governor’s office.

In publicly available dollar figures, Fred the Turtle is Hope Rising’s largest tangible offering to the state since the nonprofit’s creation. The book is promoted on Hope Rising’s website, which says 1,750 copies have been distributed in eight communities. It also asks for donations to “help Fred tour Mississippi.”

Elee Reeves’ 2022 announcement of Fred the Turtle came with a hodge podge of vaguely stated goals, such as “to build and bring resources that strengthen families and children in our state,” Cheeks said.

Russell Woods, senior director for strategic consulting at Casey Family Programs, said during the press conference that Fred the Turtle aligns with his organization’s mission to reduce the need for foster care. The organization has repeatedly declined to discuss the project with Mississippi Today.

“This project was important to invest in because it aligns with Casey’s vision to improve child wellbeing outcomes,” he said during the 2022 press conference. “And part of a healthy child development and wellbeing is literacy, education and social functioning. All of these are elements that are being effectively used in this activity book.”

The last page of the book cites several medical journals that Reeves said she used to inform her writing and the activities in the book. It also thanks several partners, including “The Casey Foundation,” “The Hope Institute,” Mississippi Department of Human Services, Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services, Mississippi Department of Education and The Cirlot Agency, the same branding agency that received $1.7 million in welfare funds for promotional materials during the Family First era.

Cirlot CEO Liza Cirlot Looser told Mississippi Today that Cirlot designed the cover and laid out the pages in Fred the Turtle for free.

Mississippi isn’t the only place in which Casey Family Programs is partnering with the spouses of governors to build support for child welfare reform.

“The spouses of governors (first spouses) can leverage their influence to advance child and family well-being,” its website states. “Although not elected officials, first spouses are important allies to child welfare leaders as they seek to collaborate with a wide range of partners, build upstream prevention services, and transform the child welfare system.”

Meanwhile, the Mississippi Department of Child Protection Services, an agency under Gov. Reeves, is still failing to draw down the unlimited federal matching funds newly offered by the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 that could be used to prevent neglect and keep families intact.

In recent weeks, the First Lady’s office issued a media blast about her book tour, during which she read Fred the Turtle to students in Canton, Jackson, Hattiesburg and Meridian. WDAM reported that Elee Reeves’ goal is to distribute 30,000 copies of her book.

Dixie Attendance Center student Brayden Cooke said this about the First Lady’s visit: “It was amazing, but I was also kind of nervous because it’s my first time seeing her and I didn’t want to act a fool.”

In the book, readers follow a character named Jimmy, a fisherman in the Gulf of Mexico. On his seafood delivery route in Hattiesburg, Fisherman Jimmy encounters a turtle he names Fred.

Together, they travel to Meridian, Columbus and the U.S. Air Force Base, Natchez, Indianola and the B.B. King Museum, Oxford, where they learn about William Faulkner, and the Mississippi State Capitol in Jackson, briefly running into Gov. Reeves. Along the journey, the book asks children to contemplate and write down their dreams, goals, fears and superpowers. Other pages ask the reader to find the turtles hiding in the Capitol building, connect the dots to finish a picture of a guitar or complete a word search.

The State’s Education Superintendent Carey Wright, who also spoke at the 2022 press conference, said the new book “shows all Mississippians how much the First Lady values the children of our state.”

Wright then turned to Reeves. “If I might say,” Wright said, “you might have another vocation waiting for you when you finish this job.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

This superintendent took a failing Delta school district to a ‘B’ rating. Now, she’s leaving

INDIANOLA — The top of the Jeep was down, and Miskia Davis was behind the wheel, leading a parade through downtown Indianola.

It was 2019, just two years after the now 50-year-old Davis became superintendent of Sunflower County Consolidated School District. Back then, she wasn’t sure this moment would ever come.

She recalled feeling the first cool breeze of October as she waved at people who lined the street, smiling and celebrating.

But it had — the district’s first “C” rating, its first passing grade, and the community had shown up to a parade to celebrate the achievement. Generations of teachers and Sunflower County graduates stood on the sidewalk, proudly cheering the assembly of cars and students.

“It was … Oh my God,” Davis said. “My children were like, ‘We did something.’”

The work hadn’t been easy, but it had been worth it, Davis thought — the number crunching, the doubt and lukewarm welcome she felt from the community, the tough decisions she’d had to make.

Now, she’s ready to move on.

Daughter of the Delta

From starting kindergarten to subbing for elementary classes, Davis’ childhood and career in Sunflower County and her identity as a daughter of the Delta were her strengths in the classroom, she said.

“I grew up in Drew, poor and with two young parents,” Davis said. “We didn’t have elaborate meals, and when I went home, the lights may have been off. But it made me who I am, and these children were experiencing the same things I experienced as a child.”

So Davis was relatable. But as a young high school teacher at Ruleville Central High School, some of her students looked older than her and many were taller than she was. She was forced to learn how to command respect, too.

One particular child taught her an invaluable lesson. He was a star football player in her biology class, and he was failing the course by two points. He caused trouble in class and Davis was determined to fail him, despite more experienced teachers prodding her not to, to look past her own ego.

So Davis gave him another chance. She had him do extra work and spent hours talking to him. She learned why he behaved poorly in class — he was one of seven children to a young, single mother.

“He was angry at the world, and I just happened to be in the world,” she said. “It taught me the power of relationships. I think that’s the most important catalyst in transforming education.”

It was during that time that her superintendent “saw something” in her and pushed her to become a school leader. That kickstarted her journey in administration.

Davis soon learned she had a particular gift for turning failing schools around. Under her leadership as principal, Ruleville Middle School went from failing to an “A” letter grade in three years.

Her school improvement strategy began to take shape, similar to her teaching style. Davis was both a disciplinarian and someone to whom teachers and students could relate. She prioritized building strong relationships with teachers who were invested in their students. But she didn’t shy away from making controversial decisions, either. In Ruleville, she fired nearly all of the staff when she arrived.

But as Davis was gaining her footing as an administrator, Sunflower County School District was struggling.

After consistent failing grades resulted in the state takeovers of Indianola, Sunflower and Drew school districts, the Legislature decided to consolidate the three systems in 2012.

District consolidation is a massive undertaking for any community, but especially for Sunflower County — smack dab in the middle of the Delta, an under-resourced region with a shrinking population, high poverty rates and a deep history of racial exploitation.

Davis arrived in 2014 to a school district that had lost hope — a district that she didn’t recognize.

All Sunflower knew was ‘failure’

Davis never wanted to be superintendent.

She spent three years working under the leader of the consolidated district. But when the superintendent was dismissed in 2017, Davis was appointed to the head role in an interim capacity. She got the job in January of 2018 without ever applying.

So with another state takeover looming, Davis went to work. The biggest challenge? The district and the community seemed resigned to failure.

“We had been failing so long, that’s all we knew,” she said. “No one was even sad.”

Early on, Davis visited a school to discuss recent test results. She was so struck by teachers’ apathy that she stopped the meeting midway and had them tear off a scrap of paper and write “yes” or “no” to a question: Did the teachers believe their school could ever be successful?

More than half said no.

“They were teaching my children,” Davis said, tearing up. “And they didn’t think they would ever be successful.”

Davis went to the school board to tell members that she wouldn’t be renewing many of those teachers’ contracts. That’s when she realized she didn’t just need to boost test scores — she needed to change attitudes.

The hashtag #WINNING was born.

“We started to celebrate every little accomplishment,” Davis said. “We got T-shirts, shades, whatever. That was our mantra.”

Children received certificates for a week of perfect attendance. When students did well on benchmark assessments, teachers were ushered into the hallway to be celebrated by students and colleagues. Davis created the “Killin’ It” awards, given to students and teachers for meeting their testing benchmarks.

They were just certificates, at the end of the day. But it led to a changed school culture, a renewed belief that they could succeed.

As an administrator, Davis leaned on what she knew worked as a teacher, relationship-building and strong discipline (she even sent her nephew to alternative school for fighting), and combined it with a data-driven approach and an eagle-eyed focus on testing.

She put an academic coach in every building, whose sole responsibility was supporting teachers.

Davis took teacher Dylan Jones out of the classroom and put him in the central office, where he was tasked with tracking district metrics.

Jones uncovered which consultants were working and which were uselessly costing the district millions. The district went from contracting with 30 firms to just four.

Jones also created an accountability system for teachers. With one click, Davis could see how each teacher’s students were performing, and she gave everyone access to the data. If teachers weren’t meeting their goals, Davis hosted regular meetings and had them explain — in front of everyone — what they needed to succeed.

Davis’ methods weren’t popular at first. Educators went to the school board and complained that the system was “punitive.” Some even quit. But Davis was steadfast and implored board members to see the work she and her team could do, if given the chance.

The district’s rating didn’t budge in 2018.

But in fall 2019, after Davis’ first full year as superintendent, Sunflower County Consolidated School District had earned its first “C” rating.

What happened after the first ‘C’

Those early years were difficult, Davis remembered, because she felt so isolated, just her and her team “in the trenches.”

She hosted community meetings, imploring local parents, leaders and business owners to support the district.

“They told me to come back when we were no longer failing,” Davis said.

So after that first “C,” when she started seeing the district’s hashtags on Facebook, when more people started coming to school events, when she started to get invited to speak at the local Rotary Club, it was bittersweet.

Teachers, too, took a while to come around. Their performance was being closely monitored through the accountability system, but soon they realized that Davis wasn’t giving them mandates outside of improving test scores. She gave them autonomy in their classrooms. Teachers had the final say on how to improve their students’ achievement. That kind of trust isn’t common, Sunflower County teachers told Mississippi Today.

It wasn’t until 2021, when voters passed a $31 million bond issue that would pay for major school renovations, that Davis felt the full support of the community.

Davis even won over Betty Petty, a local matriarch and fierce advocate for kids and parents.

“She has actually shown a presence at the schools, constantly meeting with teachers and making sure all children are learning,” Petty said. “We had community meetings where she would actually come out and listen to our concerns.”

Petty attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony at Gentry High School last July. Before renovations, plumbing problems caused flooding when it rained, so students had to wade through water to get from class to class. Davis said she’d never forget the sight of generations of Gentry graduates in the school atrium, looking around in wonder at the new facility.

“At first, I chose the community,” Davis said. “But eventually, the community chose me.”

The legacy she leaves behind

Strong schools make strong communities, but it can take time for results to show. Indianola Mayor Ken Featherstone hopes to see the dividends soon.

Featherstone took office four years ago, around the same time the district got its first “B” grade. It has maintained the grade ever since, the highest in the entire region.

He, like Davis, was reared in the Delta, but empathizes with her struggle garnering the support of a community deeply impacted by gun violence and low investment from state officials.

“People are very result-oriented,” he said, leaning back at his desk in city hall. “You till the soil, but it’s not until you start your seed breaking the ground do you see other people starting to water it. That’s just human nature.”

He’s hoping the district’s academic gains will be a boon for Indianola’s struggling economy.

“We’re seeing things slowly come to our area,” Featherstone said. “To get manufacturing jobs to come to our area, we have to improve our public school system. Directors and presidents of manufacturing plants … they need to know where their kids are going to attend school.”

Davis announced in October 2024 that she would be leaving the superintendent job at the end of the school year. Now, she travels the state, consulting with other districts on how to replicate what she did in Indianola, as a director of District and School Performance and Accountability for The Kirkland Group, an education consulting firm based in Ridgeland.

Her departure was a tough blow, Featherstone said, and leaves the district’s hard-fought success hanging in balance.

Petty and her network of parents are concerned, too.

“I don’t think any of us know what will happen moving forward,” she said.

Davis said there was no big epiphany. She just felt her mission was accomplished. She said she’s adamant that the district’s “best days are ahead,” under new superintendent James Johnson-Waldington.

Johnson-Waldington, who was most recently serving as superintendent of Greenwood Leflore Consolidated School District, is also Sunflower-grown, and he was Davis’ principal when she taught at Ruleville Central High School. He plans on employing strategies similar to Davis: holding teachers accountable and celebrating their achievements.

After all, if it’s working, why change it?

“I feel a good kind of pressure,” Johnson-Waldington said. “I like challenges, and this is a new challenge for me. I’m not taking a failing school district to success. This is about maintaining and growing, and I accept that challenge for the very reason that this is home. I’m going to work very hard to maintain what Miskia has done.”

Davis leaves behind a legacy, Featherstone said, that makes her hometown proud. He was in the crowd that day at the parade. He remembers the excitement, the pride.

“Older teachers were there, and you could see the look on their faces that they knew they had reared someone who threw the oar out to a sinking district and brought it back up,” he said.

“She made us see ourselves in a better light, and we can’t thank her enough.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post This superintendent took a failing Delta school district to a ‘B’ rating. Now, she’s leaving appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a positive and detailed profile of an educational leader working to improve a struggling school district in a historically under-resourced and economically challenged region. The focus on community uplift, education reform, accountability, and addressing systemic challenges aligns with themes often emphasized by center-left perspectives. However, the article maintains a largely neutral and factual tone without overt political framing or partisan language, emphasizing pragmatic solutions and community collaboration rather than ideological positions.

Mississippi Today

Theology student’s ‘brain drains back home’ despite economics, safety concerns

Editor’s note: This Mississippi Today Ideas essay is published as part of our Brain Drain project, which seeks answers to why Mississippians move out of state. To read more about the project, click here.

Though I imagine I’ll never return, more often than not, my brain drains back to Mississippi. My whole adult life has been a journey up and down the Hudson River, from New York City to the Adirondacks, but inevitably, I find my thoughts leaking toward another river.

I grew up fearing being left behind in the Rapture, but in earnest, it feels like I’m the one who left everyone behind. I’m not proud of this, but I’m certainly not ashamed. I have roots in the Northeast now, and a life that isn’t easily transplanted elsewhere, especially to the Red Clay Hills of Neshoba County. Life took me from Mississippi, and life keeps me away.

I left Mississippi for New York in 2015, and I estimate that I’ve returned only 11 times. My sporadic trips home have been mostly because I’m consistently broke, but now it’s a combination of that and concerns for my safety.

My mother, also limited by finances and Mississippi’s minimum wage, has visited me twice in 10 years, once in the spring of 2016 and then when I graduated from Yale Divinity School in 2023.

I haven’t been back since I came out as a trans woman and began medically transitioning in the winter of 2024. I try not to be overwhelmed with guilt or grief for the imagined, shared life I don’t experience with my mother. Rather, I’ve learned to cherish what we do have.

It’s strange to be who I am, mostly for her but also for me. She has learned to love me regardless of whether or not she understands what I’m doing. In her mind, if you go to college, you become a nurse or a lawyer. You settle down, probably in Jackson, maybe Oxford, most likely in my hometown of Philadelphia, and commute by car more than an hour to work. You probably see your mom weekly. She sees her grandkids as often as possible.

That is not how life turned out. We do talk on the phone. Sometimes we get into once-a-week phone call sprees, other times, I drop off for weeks, maybe a month, when I’m depressed.

When I come home, she picks me up from the airport and drives me back a few weeks later. We crack the windows, smoke cheap Mississippi cigarettes and try to cram 10 years of a strange-to-us mother-daughter relationship into a 90-minute ride to the airport in Jackson. Usually, we talk about suffering, death, sin, God, the end of the world, and what the hell I am doing with my life.

You go to college to get a job, to make more money than your parents and to buy a strange suburban-but-rural McMansion just beyond city limits where you start a family around the age of 25 at the latest.

According to my mother, I went to the University of Mississippi and got brainwashed. She tells me often that it’s like she doesn’t know who I am, and she’s mostly right. She hasn’t met anyone I’ve dated in person since high school. She hasn’t seen me in person since transitioning, and I changed my name to Romy. I explain my relationship with my family to friends, peers, new partners and congregations, always with an articulate sense of heartbreak that I’ve learned to intellectualize and package up in a story of “working-class origins,” single motherhood, a white Christian nationalist rural community and my stumbling through adulthood “refusing not to live by my values.”

I originally left Mississippi to be an AmeriCorps Vista volunteer in the Capital Region of New York. I’d never been there. I took a Greyhound from Memphis to New York City to Albany, New York with two large suitcases and a backpack. Several of my friends from college had moved to New York City, and their couches and shared beds provided a safe launching pad for more of us. I had also fallen in love with a fashion student turned designer that I met on a trip to the city the year prior. Though that romance flamed and flickered for many years and ultimately flamed out, my reason for staying in the North was the life I was increasingly stumbling into.

I went there because, at the time, I had an insatiable desire to live out my values and politics. After all, I was maybe one of two socialist public policy majors at the Trent Lott Leadership Institute at the University of Mississippi, and I didn’t want to be a lawyer, a lobbyist or a policy wonk.

I wanted to be poor and engage in building sustainable autonomous communities. I wanted to learn how to be a person who had no work/life distinction, but a vocation and calling.

Through AmeriCorps, I luckily found a small group of activists, urban homestead types, organizers and ex-social workers living together helping others at the margins and themselves start businesses and worker-cooperatives while struggling through mental health crises, and taking on an impossible but seemingly always plausible dream of a directly democratic community owned, operated and governed only by those who live there.

This was my first “job” out of college. It was my dream come true, and the most difficult thing I’d ever done. I burnt out pretty hard after two years, and probably made somewhere between $25,000 and $30,000 during that whole time. Since then, the most I’ve made in a year is my current PhD stipend of about $34,000.

I was, however, helped along by friends, colleagues and the activist communities that I was stumbling into. Through them, I was encouraged to go to Union Theological Seminary, land a job at a prestigious artist residency in the mountains, go to Yale Divinity School, discern that I was called to be a priest and come to know myself as a trans woman.

My life outside of Mississippi has been sustained solely by relationships that transgress the boundaries between work and life, co-workers and friends. I regularly reflect on and often worry about how fragile this all is, and if my own vocational and intellectual pursuits have been worth what I’ve left behind or never had.

I’m not sure I’ll ever know. However, I’ve managed to find profound meaning in it all so far, and it keeps me digging myself into this hole in which I will hopefully find what I am looking for, or dig my own damn grave.

Originally from Philadelphia, Romy Felder (she/her) is currently a PhD student at Union Theological Seminary. She is also pursuing the priesthood in the Episcopal Diocese of New York. She has a background in worker-cooperative development, community organizing, popular education and arts management. Romy lives cavalierly but contentedly in Brooklyn, New York.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Theology student's 'brain drains back home' despite economics, safety concerns appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Left-Leaning

This essay reflects a distinctly personal and ideological perspective rather than neutral reporting. The author frames Mississippi as economically limiting and socially unsafe, particularly for marginalized identities such as transgender individuals, while presenting Northern activist and academic communities in a sympathetic and aspirational light. References to socialism, worker-cooperatives, and critiques of conservative Mississippi culture suggest a worldview aligned with progressive or left-leaning politics. The tone is introspective and critical of traditional Southern expectations, while valorizing alternative, activist-driven lifestyles. As such, the piece is less about balanced reporting and more an expression of lived experience through a progressive lens.

Mississippi Today

‘Get a life,’ Sen. Roger Wicker says of constituents

A note from Adam Ganucheau: A couple hours after this column published, Sen. Roger Wicker’s office reached out and demanded a correction, saying the senator’s “get a life” comment was directed to himself and not to constituents. That’s certainly not how I nor hundreds of Mississippians who commented on and shared the viral video heard it. Mississippi Today has updated portions of this column to reflect concerns raised by Wicker’s office. Here’s a link to the video/audio of his response to the question about constituent concerns. Mississippians can decide for themselves what Wicker meant.

When 34-year-old Thad Cochran arrived in Washington after his first election in 1972, the Republican felt it important to document what he’d heard and learned from Mississippians on the campaign trail and share it with his young staff.

He sat down at a typewriter and wrote a memo titled “General Responsiveness” and dated March 14, 1973:

During the campaign I detected a very strong animosity among the people toward government and those associated with government bureaus and agencies. This included elected officials and those associated with them. Part of the cause of this attitude was due to a lack of feeling or understanding by government people for the needs and opinions of the average citizen. We are all in a job to represent all our constituents. We are not the bureaucracy. A constituent who asks us for help should be assured to be in need of help with our office as his last resort. A constituent who writes a letter should be made to feel by our response that he is glad he wrote us. A constituent who claims to have been wronged by the government should be assumed to be correct. Everyone should guard against developing the attitude that we are better than, smarter than or more important than any constituent. We do not hold a position of authority over any constituent. We are truly servants of the people who selected us for this job.

Every year from 1973 through 2018, over his three U.S. House terms and six U.S. Senate terms, Cochran shared that memo with every staffer who worked in his offices. The guidance, he said all those years, was a necessary reminder to show respect to the people who offer feedback or need help. He never wanted his staff or himself to forget who sent them to Washington.

The memo, like so many other things, serves as a stark reminder that Cochran was among the last in a bygone era of American politics. The perspective he wrote and shared is a far cry from what Mississippians have been getting recently from our current U.S. senators.

“Surely everybody else has better things to do with their time,” senior U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker said to a room full of constituents earlier this month when asked about calls and emails his office has been getting. After half-heartedly explaining that he does see a list of names of people who reach out to his office, he quipped: “Get a life.”

Wicker’s office said Friday that the senator directed “Get a life” to himself, not to constituents.

Wicker, who typically chooses his words a little more carefully, perhaps has been trying to match his junior colleague’s energy.

“Why is everyone’s head exploding?” U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith said in April to Mississippi constituents who had expressed concerns over slashing federal Medicaid spending. “I can’t understand why everyone’s head is exploding.”

There are many kind staffers working for Republicans Wicker and Hyde-Smith who are helpful to Mississippi constituents in any number of ways privately or behind the scenes. These people care deeply about serving their home state and they do it well, and they cannot help how their bosses address the public. But, boy, their phones must be blowing up more than ever since the senators made these comments.

Consider, for a moment, what it means that we have devolved from having a leader who believed that “a constituent who claims to have been wronged by the government should be assumed to be correct” to one who thinks telling constituents to “get a life” is appropriate. Think about the fact that we replaced a leader who regularly reminded his staff that “we are truly servants of the people who selected us for this job” with one whose gut response to legitimate concerns from constituents is that their “heads are exploding.”

Just … wow. To call it alarming doesn’t fully encapsulate the gravity of their behavior. It’s enough to discourage even the most optimistic among us about the present and future of our state and our nation.

It’s enough to inspire you to ponder, in this intense political climate when unprecedented and harrowing federal government decisions are being made and going largely unchecked every day, whether our current U.S. senators even remember why they’re in Washington, why we sent them there.

It is necessary, in the shortest possible order, to ask and answer for ourselves what we should expect of our elected officials and whether we should feel OK about being dismissed or ignored outright like this.

You don’t have to be a Democrat to think that this behavior is out of line. Plenty of Republicans — some publicly and many privately — are increasingly disturbed by what’s happening in Washington. Regardless of your own personal political beliefs, be honest with yourself about whether you can read these comments from our senators and still feel that your best interests are being represented.

Sadly, we can no longer ask Cochran to help us answer these questions, but it sure seems clear where he’d stand. What about you?

READ MORE: Mississippi, where ‘We Dissent’ means nothing to elected officials

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post 'Get a life,' Sen. Roger Wicker says of constituents appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content critiques Republican senators for their dismissive attitude toward constituents, contrasting them with a more respectful past leader. It highlights concerns about current political behavior and governance, emphasizing accountability and responsiveness to the public. While it acknowledges that some Republicans privately share these concerns, the tone and framing suggest a leaning that favors more progressive or reform-minded perspectives, typical of center-left commentary.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed3 days ago

New Texas laws go into effect as school year starts

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

Kratom poisoning calls climb in Texas

-

News from the South - Tennessee News Feed5 days ago

GRAPHIC VIDEO WARNING: Man shot several times at point-blank range outside Memphis convenience store

-

News from the South - Florida News Feed3 days ago

Floridians lose tens of millions to romance scams

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed5 days ago

Unsealed warrant reveals IRS claims of millions in unreported sales at Central Kentucky restaurants

-

Mississippi Today5 days ago

‘Get a life,’ Sen. Roger Wicker says of constituents

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

Woman charged in 2024 drowning death of Logan County toddler appears in court

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Leavenworth mother found guilty in death of 1-year-old daughter