Mississippi Today

State insurance premium hike blunts teacher pay raise

State insurance premium hike blunts teacher pay raise

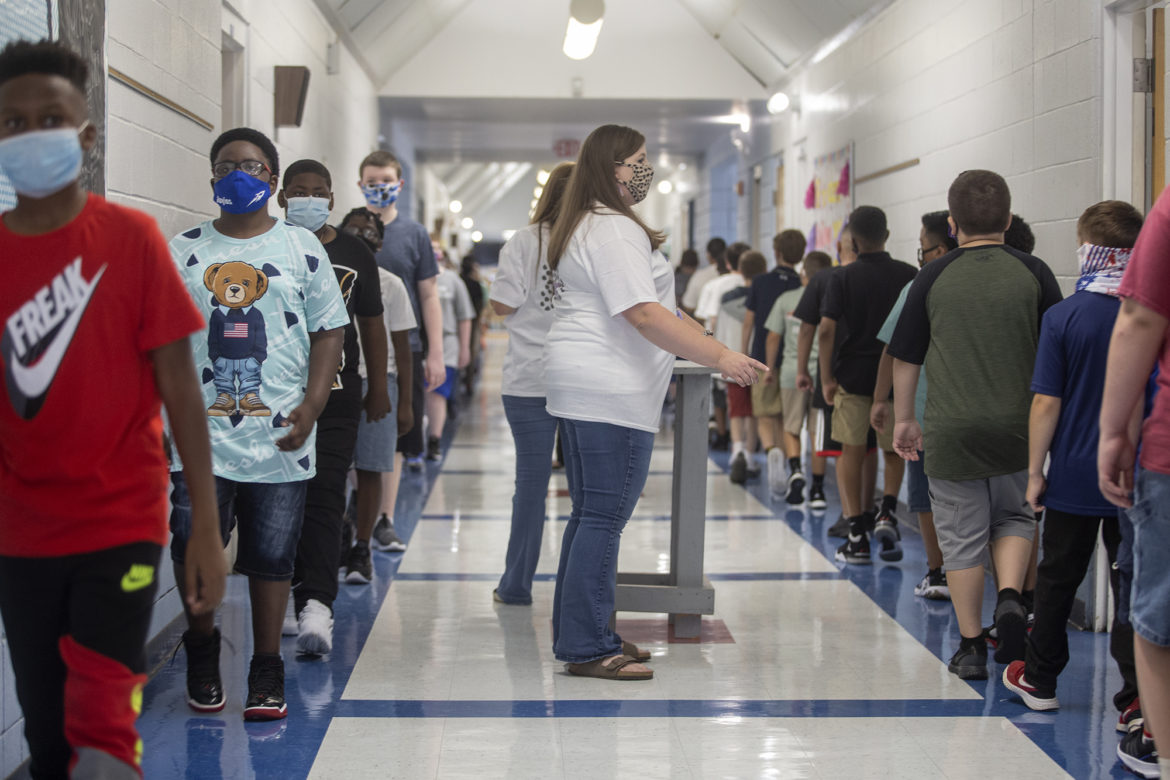

Athena Lindsey, a teacher and policy fellow with Teach Plus Mississippi, repeatedly heard the same concern when surveying teachers in the lead-up to the historic 2022 teacher pay raise: “Every time you see a pay increase, the insurance premiums always go up, so you never really get to feel the actual pay raise.”

Insurance premiums for public employees rose 6% on Jan. 1 of this year, the fifth consecutive year with an increase. The report of the Teach Plus Mississippi survey showed lower insurance premiums as the third highest policy priority for teachers, behind two related to pay increases.

“A lot of them in the survey said that they had second jobs just for that reason, because the insurance plans were ridiculous,” said Lindsey.

The average teacher salary in Mississippi is $53,000, which drops to $40,990 after taxes and retirement contributions, according to calculations by Mississippi First. Premiums for individuals on the plan make up 1% of their take home pay, but 25% for employees with their family on the state insurance. After premiums, take home pay for employees with their family on the plan drops to $30,910.

Five teachers interviewed by Mississippi Today expressed growing frustration with the rising costs and falling benefit quality. State officials say these changes were made to counter rising health insurance costs that are causing financial deficits, with the reserves of the state plan dropping $119 million over the past nine years. Legislators say they are looking to address this problem next session.

The state health plan served nearly 194,000 state employees and their dependents in 2021, the most recent year for which there is data. Most people opt for the “Select” plan with more benefits, but the number of people on that plan has been slowly falling since 2016.

Premium costs have remained largely unchanged for individuals on the single-employee plan, but people whose families also receive insurance through the state plan have seen more significant increases.

Per state law, the state contributes 100% of the premium cost for basic coverage for employees. Employees pay between $20-46 monthly for individual coverage if they opt for the plan with more benefits. The state does not contribute to premium costs for children and spouses, making family coverage significantly more expensive. Prices range between $124 and $840 a month, and vary based on the number of dependents and quality of coverage.

Mississippi is one of two states in the Southeast that doesn’t pay any extra towards premiums for family coverage, according to figures compiled by the Mississippi Department of Finance and Administration that were presented at a 2021 hearing. Rep. Kent McCarty, R-Hattiesburg, introduced a bill this session for the state to pay 50% of dependent premiums, but it died in committee.

“A lot of jobs are offering coverage for dependents already, and a lot of times teachers leave to take those jobs, so we thought this could be a way to make the teaching profession more competitive with others and keep teachers in the classroom,” he said.

A recent report published by Mississippi First studied why teachers are leaving the classroom. In it’s survey, 42% said they could not afford deductibles, premiums, or other health care costs not covered by insurance, and financial insecurity was closely linked with risk of leaving the classroom.

“Any improvement in this area, whether that is reducing cost for teachers or improving the quality of the plan, is all going to necessitate more resources from the state,” said Toren Ballard, K-12 policy director for Mississippi First.

This gap between individual and family premiums is common in the teaching profession. According to a 2020 report published by the Southern Regional Education Board, teachers pay an average of $200 less in monthly premiums for single plans than private sector employees, but an average of $257 more in premiums for family plans.

Megan Boren, project manager with the board, said her study of teacher compensation found most states in the Southeast have work to do because of the sizable cost gap between single and family coverage. Boren said she would not single out Mississippi as struggling in this area, but pointed to Alabama, Virginia, and Florida as exemplar states that have successfully kept costs down for employees.

“A lot of this is just tied to how health insurance is set up, and there’s not a lot of wiggle room or great strategies that an employer, government or otherwise, can take on these pieces,” Boren said. “Our hands are quite tied because of the way health insurance is structured in this country and some of the general policies around that.”

A bill moving through the Legislature this session would study the state health insurance system and make recommendations for legislation to be proposed in 2024. The task force, proposed by Senate Education Committee Chairman Dennis DeBar, R-Leaksville, would focus on the financial solvency of the plan, rate increases, benefits and comparisons to other Southeastern states.

“I just want to see a deep dive into why expenses keep going up and up,” DeBar said. “I don’t want insurance (costs) to be a deterrent to getting insurance and doing yearly check-ups, because on the back end, medical conditions may be worse off if people don’t treat them.”

Some teachers share his concern that current rates are discouraging employees from seeking preventive care.

“I get that if you have a catastrophic year, it’s there for you, but this should be so much more in a state that is so unhealthy,” said Jason Reid, a teacher in the DeSoto County School District.

Reid, a two-time cancer patient, has hit his out-of-pocket maximum with both diagnoses and experienced the safety net that the plan can provide, but said that because of rising costs, most of his colleagues feel like they never see a benefit. Reid added the insurance plan usually isn’t stopping people from becoming teachers, but that it is driving them away.

Advocates say a lack of investment from the state is also driving away other state employees. Brenda Scott, the president of the Mississippi Alliance of State Employees, said teachers got a “decent” raise last year, but that for other state workers, raises are “very rare.”

Scott said she would like to see raises for state employees to make it easier for them to afford premium increases when they come along, or for the state to expand Medicaid to give employees more coverage options.

READ MORE: Q&A: What is Medicaid expansion, really?

“They’re not expanding Medicaid, which is meant to cover the working poor,” she said. “There’s a lot of state employees who would fit into that category.”

Adding to frustration with the insurance premium increase are other changes to the plan.

Multiple teachers expressed frustration with the declining quality of prescription drug coverage since the switch from Prime Therapeutics to CVS Caremark, a change that state officials said was made to save money on rising healthcare costs.

Renee Webber-Butler, a teacher in the Perry County School District, was informed after the switch that the ADHD medicine her 16-year-old son takes would no longer be covered. He had tried multiple medications and had negative side effects with some before finding success with Vyvanse, the medicine that was no longer being covered.

“I explained to him what was going on, and he said, ‘Mom, I’m not going to have to take that medicine where I’m mean and angry am I?’” Webber-Butler said. “How do you look at your kid and say, ‘Well, son, I’m sorry but … on educator salaries, we can’t (pay out of pocket.)’”

She said they found another medicine for him that will be covered, but called it “ridiculous” that her son has been on three different medicines in six months.

Cindy Bradshaw, the administrator of the state health insurance plan, said the switch to CVS Caremark, as well as the deductible and premium increases in recent years, are adjustments to balance the finances of the health insurance plan. The plan has been spending more on care than premiums could cover every year since 2016, which has significantly decreased the surplus reserves of the plan. The surplus was $247 million in 2012 and had dwindled to $64 million by the end of 2021, according to the plan’s actuarial report for 2021.

During the 2022 legislative session, the state health insurance plan was given $60 million in American Rescue Plan funds, and a bill has passed out of committee to give the plan another $30 million in federal pandemic relief funds this session.

When discussing the incremental actions of the state board that manages the health insurance plan, Bradshaw said, “We’re trying to softly land a plane instead of having a big crash.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Mississippi Today

Two Mississippi media companies appeal Supreme Court ruling on sealed court files

A three-judge panel of the Mississippi Supreme Court has ruled that court records in a politically charged business dispute will remain confidential, even though courts are supposed to be open to the public.

The panel, comprised of Justice Josiah Coleman, Justice James Maxwell and Justice Robert Chamberlin, denied a request from Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald that sought to force Chancery Judge Neil Harris to unseal court records in a Jackson County Chancery Court case or conduct a hearing on unsealing the court records.

The Supreme Court panel did not address whether Harris erred by sealing court records and it has not forced the judge to comply with the court’s prior landmark decisions detailing how judges are allowed to seal court records in extraordinary circumstances.

The case in question has drawn a great deal of public interest. The lawsuit seeks to dissolve a company called Securix Mississippi LLC that used traffic cameras to ticket uninsured motorists in numerous cities in the state.

The uninsured motorist venture has since been disbanded and is the subject of two federal lawsuits, neither of which are under seal. In one federal case, an attorney said the chancery court file was sealed to protect the political reputations of the people involved.

READ MORE: Private business ticketed uninsured Mississippi vehicle owners. Then the program blew up.

Quinton Dickerson and Josh Gregory, two of the leaders of QJR, are the owners of Frontier Strategies. Frontier is a consulting firm that has advised numerous elected officials, including four sitting Supreme Court justices. The three justices who considered the media’s motion for relief were not clients of Frontier.

The two news outlets on Thursday filed a motion asking the Supreme Court for a rehearing.

Courts are open to public

In their motion for a rehearing, the media companies are asking that the Supreme Court send the case back to chancery court, where Harris should be required to give notice and hold a hearing to discuss unsealing the remaining court files.

Courts and court files are supposed to be open and accessible to the public. The Supreme Court has, since 1990, followed a ruling that lays out a procedure judges are supposed to follow before closing any part of a court file. The judge is supposed to give 24 hours notice, then hold a hearing that gives the public, including the media, an opportunity to object.

At the hearing, the judge must consider alternatives to closure and state any reasons for sealing records.

Instead, Harris closed the court record without explanation the same day the case was filed in September 2024. In June, Harris denied a motion from Mississippi Today to unseal the file.

The case, he wrote in his order, is between two private companies. “There are no public entities included as parties,” he wrote, “and there are no public funds at issue. Other than curiosity regarding issues between private parties, there is no public interest involved.”

But that is at least partially incorrect. The case involves Securix Mississippi working with city police departments to ticket uninsured motorists. The Mississippi Department of Public Safety had signed off on the program and was supposed to be receiving a share of the revenue.

Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald then filed for relief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Harris improperly closed the court file without notice and did not conduct a hearing to consider alternatives.

After the media outlets’ appeal to the Supreme Court, Harris ordered some of the records in the case to be unsealed.

But he left an unknown number of exhibits under seal, saying they contain “financial information” and are being held in a folder in the Chancery Clerk’s Office.

File improperly sealed, media argues

The three-judge Supreme Court panel determined the media appeal was no longer relevant because Harris had partially unsealed the court file.

In the news outlets’ appeal for rehearing, they argue that if the Supreme Court does not grant the motion, the state’s highest court would virtually give the press and public no recourse to push back on judges when they question whether court records were improperly sealed.

“The original … sealing of the entire file violated several rights of the public and press … which if not overruled will be capable of repetition yet, evading review,” the motion reads.

The media companies also argue that Harris’ order partially unsealing the chancery court case was not part of the record on appeal and should not have been considered by the Supreme Court. His order to partially unseal the case came 10 days after Mississippi Today and the Sun Herald filed their appeal to the Supreme Court.

READ MORE: Judge holds secret hearing in business fight over uninsured motorist enforcement

Charlie Mitchell, a lawyer and former newspaper editor who has taught media law at the University of Mississippi for years, called Judge Harris’ initial order keeping the case sealed “illogical.” He said the judge’s second order partially unsealing the case appears “much closer” to meeting the court’s standard for keeping records sealed, but the judge could still be more specific and transparent in his orders.

Instead of simply labeling the sealed records as “financial information,” Mitchell said the Supreme Court could promote transparency in the judiciary by ordering Harris to conduct a hearing — something he should have done from the outset — or redact portions of the exhibits.

“Closing a record or court matter as the preference of the parties is never — repeat never — appropriate,” Mitchell said. “It sounds harsh, but if parties don’t want the public to know about their disputes, they should resolve their differences, as most do, without filing anything in a state or federal court.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Two Mississippi media companies appeal Supreme Court ruling on sealed court files appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

The content focuses on transparency, accountability, and the public’s right to access court records, which aligns with values often emphasized by center-left perspectives. It critiques the sealing of court documents and advocates for media and public oversight of judicial processes, reflecting a concern for government openness and checks on power. However, the article maintains a factual tone without overt political partisanship, situating it slightly left of center due to its emphasis on transparency and media rights.

Mississippi Today

Judge: Felony disenfranchisement a factor in ruling on Mississippi Supreme Court districts

The large number of Mississippians with voting rights stripped for life because they committed a disenfranchising felony was a significant factor in a federal judge determining that current state Supreme Court districts dilute Black voting strength.

U.S. District Judge Sharion Aycock, who was appointed to the federal bench by George W. Bush, last week ruled that Mississippi’s Supreme Court districts violate the federal Voting Rights Act and that the state cannot use the same maps in future elections.

Mississippi law establishes three Supreme Court districts, commonly referred to as the northern, central and southern districts. Voters elect three judges from each to the nine-member court. These districts have not been redrawn since 1987.

READ MORE: Mississippians ask U.S. Supreme court to strike state’s Jim Crow-era felony voting ban

The main district at issue in the case is the central district, which comprises many parts of the majority-Black Delta and the majority-Black Jackson Metro Area.

Several civil rights legal organizations filed a lawsuit on behalf of Black citizens, candidates, and elected officials, arguing that the central district does not provide Black voters with a realistic chance to elect a candidate of their choice.

The state defended the districts arguing the map allows a fair chance for Black candidates. Aycock sided with the plaintiffs and is allowing the Legislature to redraw the districts.

The attorney general’s office could appeal the ruling to the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. A spokesperson for the office stated that the office is reviewing Aycock’s decision, but did not confirm whether the office plans to appeal.

In her ruling, Aycock cited the testimony of William Cooper, the plaintiff’s demographic and redistricting expert, who estimated that 56,000 felons were unable to vote statewide based on a review of court records from 1994 to 2017. He estimated 60% of those were determined to be Black Mississippians.

Cooper testified that the high number of people who were disenfranchised contributed to the Black voting age population falling below 50% in the central district.

Attorneys from Attorney General Lynn Fitch’s office defended the state. They disputed Cooper’s calculations, but Aycock rejected their arguments.

The AG’s office also said Aycock should not put much weight on the number of disenfranchised people because the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals previously ruled that Mississippi’s disenfranchisement system doesn’t violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Aycock, however, distinguished between the appellate court’s ruling that the system did not have racial discriminatory intent and the current issue of the practice having a racially discriminatory impact.

“Notably, though, that decision addressed only whether there was discriminatory intent as required to prove an Equal Protection claim,” Aycock wrote. “The Fifth Circuit did not conclude that Mississippi’s felon disenfranchisement laws have no racially disparate impact.”

Mississippi has one of the harshest disenfranchisement systems in the nation and a convoluted method for restoring voting rights to people.

Other than receiving a pardon from the governor, the only way for someone to regain their voting rights is if two-thirds of legislators from both chambers at the Capitol, the highest threshold in the Legislature, agree to restore their suffrage.

Lawmakers only consider about a dozen or so suffrage restoration bills during the session, and they’re typically among the last items lawmakers take up before they adjourn for the year.

Under the Mississippi Constitution, people convicted of a list of 10 types of felonies lose their voting rights for life. Opinions from the Mississippi Attorney General’s Office have since expanded the list of specific disenfranchising felonies to 23.

The practice of stripping voting rights away from people for life is a holdover from the Jim Crow era. The framers of the 1890 Mississippi Constitution believed Black people were most likely to commit certain crimes.

Leaders in the state House have attempted to overhaul the system, but none have gained any significant traction in both chambers at the Capitol.

Last year, House Constitution Chairman Price Wallace, a Republican from Mendenhall, advocated a constitutional amendment that would have removed nonviolent offenses from the list of disenfranchising felonies, but he never brought it up for a vote in the House.

Wallace and House Elections Chairman Noah Sanford, a Republican from Collins, are leading a study committee on Sept. 11 to explore reforms to the felony suffrage system and other voting legislation.

Wallace previously said on an episode of Mississippi Today’s “The Other Side” podcast that he believes the state should tackle the issue because one of his core values, part of his upbringing, is giving people a second chance, especially once they’ve made up for a mistake.

“This issue is not a Republican or Democratic issue,” Wallace said. “It allows a woman or a man, whatever the case may be, the opportunity to have their voice heard in their local elections. Like I said, they’re out there working. They’re paying taxes just like you and me. And yet they can’t have a decision in who represents them in their local government.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Judge: Felony disenfranchisement a factor in ruling on Mississippi Supreme Court districts appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a focus on voting rights and racial justice issues, highlighting the impact of felony disenfranchisement on Black voters in Mississippi. It emphasizes civil rights concerns and critiques longstanding policies rooted in the Jim Crow era, which aligns with center-left perspectives advocating for expanded voting access and systemic reform. The coverage is factual and includes viewpoints from multiple sides, but the framing and emphasis on racial disparities and voting rights restoration suggest a center-left leaning.

Mississippi Today

Jackson police chief steps down to take another job, national search to come

Jackson Police Department Chief Joseph Wade told the mayor last week he was choosing to retire after 29 years of service and two years at the helm of the force. Wade said he’d been given another job opportunity, which has yet to be announced.

His last day is Sept. 5.

Mayor John Horhn said he told Wade the officer would be crazy not to take the job — one that comes with less stress and more pay.

“His wife has been on his back, his blood pressure has been up,” Horhn said during Tuesday’s City Council meeting. “He has done a commendable job.”

Wade became chief during a period in which Jackson was called the murder capital of America. Under his tenure, Wade said crime has fallen markedly, including a roughly 45% reduction in homicides so far this year compared to the same period in 2024, the Clarion Ledger reported. He said he’s also increased JPD’s force by 37, for a total of 258 officers.

Wade said his biggest accomplishment is reestablishing trust. “We are no longer the laughing stock of the law enforcement community,” he said.

The chief’s departure comes less than two months after Horhn took office, replacing former Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba who originally appointed Wade, and on the heels of a spate of shootings that Wade said were driven by gangs of young men.

“I have received so many calls from the community: ‘Chief, please don’t leave us,'” Wade told the crowd in council chambers.

But Wade said he “would rather leave prematurely than overstay my welcome,” adding that the average tenure of a police chief is 2.5 years.

Wade said that last year he stood next to Jackson Councilman Kenny Stokes and told the media he was going to cut crime in half, “And what did I do? Cut it in half,” he said.

“What I’ve seen in our community in some situations is people want police, but they don’t want to be policed,” Wade said.

Hinds County Sheriff Tyree Jones will serve as interim police chief until the administration finds a replacement. Jones said he has not finalized a contract with the city, responding to a question about whether he will draw a salary from both agencies.

“I could think of no one better than the sheriff of Hinds County,” Horhn said, adding that the appointment is temporary.

Jones said during the meeting that his responsibility as sheriff will continue uninterrupted and that his goal within JPD is to ensure continued professionalism in the department.

“I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my dear friend and retired police chief Joe Wade,” Jones said. “Again, let me be clear, I have no aspirations to permanently hold the position.”

Horhn said there is precedence for the dual role that “Chief Sheriff Jones is about to embark upon,” citing former mayor Frank Melton’s hiring of Sheriff Malcolm McMillin.

The city has enlisted help from former U.S. Marshal George White and the former chief of the Mississippi Highway Patrol, Col. Charles Haynes, to lead the Law Enforcement Task Force that will conduct a nationwide search to fill the position. The administration expects that to take between 30 and 60 days, according to a city press release.

The release said the task force will also examine safety challenges in Jackson more broadly, such as youth crime, drug crimes, departmental needs and interagency coordination.

“I am grateful that Marshal White and Col. Haynes have agreed to lead this important effort. Their breadth of experience, commitment to public safety and deep understanding of law enforcement challenges will ensure the task force conducts a rigorous search for our next chief,” said Horhn. “I am confident they will help shape solutions that address the evolving needs of Jackson.”

The city said it would soon release details about the opportunity for the public to offer input on the process.

“Hinds County is all in for whatever we have to do to make Jackson and Hinds County the safest it can be,” Hinds County Supervisors President Robert Graham said during the meeting.

Wade, who hails from nearby Terry, graduated from JPD’s 23rd recruit class in 1995, rising from a police recruit and hitting every rung of the ladder on his way to chief. “I was homegrown,” he said.

Wade said he received “an amazing offer in a private sector at an amazing organization. Don’t ask me where. That will be released at the appropriate time.”

This story may be updated.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Jackson police chief steps down to take another job, national search to come appeared first on mississippitoday.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Centrist

The article presents a straightforward news report on the resignation of a police chief, focusing on facts, quotes from officials, and crime statistics without evident ideological framing. It covers perspectives from multiple local government figures and avoids partisan language, reflecting a neutral, balanced tone typical of centrist reporting.

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed5 days ago

DEA agents uncover 'torture chamber,' buried drugs and bones at Kentucky home

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed3 days ago

Racism Wrapped in Rural Warmth

-

News from the South - Missouri News Feed7 days ago

Missouri settles lawsuit over prison isolation policies for people with HIV

-

The Center Square7 days ago

Georgia ICE arrests up 367 percent from 2021, making for ‘safer streets, open jobs | Georgia

-

Local News7 days ago

Florida must stop expanding ‘Alligator Alcatraz’ immigration center, judge says

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Quintissa Peake, ‘sickle cell warrior’ and champion for blood donation, dies at 44

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

The Dixon: Writing a New Story for Main Street in Natchez

-

News from the South - Oklahoma News Feed7 days ago

Tom Cole’s Powerful Spot on the Appropriations Committee Is Motivating Him to Stay in Congress