News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Why did Swannanoa become Helene’s ‘ground zero’? Deadly combination of topography, development and a ‘tidal wave’ of water • Asheville Watchdog

The floodwaters rose so fast at Thanh Bui’s house the morning of Sept. 27, she had to swim to safety.

Bui, 55, and her 30-year-old son, Quintin Ho, had been up much of the night, monitoring the howling winds and rainfall of Tropical Storm Helene. Ho periodically checked the yard of their home on Asheville Road, just off U.S. 70 in Swannanoa.

“At 6 a.m., I came out, and the water was already past a point of saving some of the cars,” Ho said. “At that point, we waited. It was like 8 a.m., and it was to the steps at the house, and we’re like, ‘OK, we gotta go! We started packing up, and then pretty much, while we’re coming out, it’s almost to our chest.”

Ho stands about 6 feet tall, so he was able to make it through vigorous wading, but his mom is about a foot shorter. Bui said she literally swam through her submerged front yard.

They made it to the Dunkin’ Donuts about 50 yards away and just high enough to be dry. They had moved one car there and were able to drive to Dollar General.

“We sat there for a little bit to figure out what we can do, because we was all wet and stuff,” Bui said. “For three days, we slept in wet clothes. No food for three days.”

Many wonder why Swannanoa, an unincorporated community of about 5,000 people 10 miles to the east of Asheville, was hit so hard by Helene.

Ringed by mountains, the town sits in a deep, narrow valley. The town’s location and topography, along with its development and the sheer amount of rainfall – more than 13 inches – created what county and city officials have referred to as Helene’s “ground zero,” with widespread destruction and a death toll that remains unknown more than three weeks later.

Residents are grappling with the devastation, which remains not only along the main commercial corridor of U.S. 70, but also in the modest cottages of the former Beacon Mill village and the higher-end neighborhoods along the usually placid Swannanoa River. People there are still trying to figure out how to navigate an uncertain future.

A self-described “lunch lady” at Black Mountain Elementary School, Bui bought her one-story Swannanoa home 22 years ago for $89,000 and raised her son and daughter, Quinho, 22, there.

“This hasn’t happened in the area like this, I heard, since 1916,” Ho said. “So no one expected it at all. And you see what happened. Nobody was prepared.”

His mother, wearing rubber boots, gloves and a facemask while taking a break from searching the brick ranch house for family photos, said the Swannanoa River is relatively far away, on the other side of U.S. 70.

But that distance didn’t stop the water from reaching up to the eaves of her home, leaving the inside a shambles and depositing other people’s cars in the backyard.

“It’s never happened this way. Never,” Bui said. “That’s why everybody was in shock. Twenty two years I lived here, it’s never been like this.”

Swannanoa Valley has a huge drainage area

The Swannanoa River, which runs from east to west from Black Mountain to Asheville, reached historic levels Sept. 27. It peaked at 27.33 feet at 3:45 p.m., according to U.S. Geological Survey gauge data. Four days earlier, it was flowing at 1.44 feet.

Philip Prince, a professional geologist and adjunct professor at Virginia Tech University, has been studying Helene’s effects in western North Carolina. He noted that the Swannanoa Valley is about 4.5 miles long and “not much over one mile wide in the area that flooded badly.”

In all, about 60 square miles drain to the portion of Swannanoa that flooded so destructively, Prince said, noting that the valley is ringed by big mountains.

“On the south side of Swannanoa, you’ve got the Swannanoa Mountains, which the top of them is 4,200 feet above sea level, which is about 2,000 feet higher than the rest of the Blue Ridge,” Prince said. “And then on the north side of Swannanoa, you go all the way up to about 6,000 feet.”

This means the valley became the receptacle for all of the rainfall hitting the area, which according to the National Weather Service, was 13.21 inches from Sept. 25 through Sept. 27.

Water from the river and the dozens of creeks that crease the mountains and the City of Asheville’s North Fork reservoir’s two spillways in Black Mountain ended up in the highly developed valley.

“The water was obviously extremely forceful when it was fully out of the channel of the river,” Prince said. “You go across 70 and there’s still houses that are pushed and smashed up, and that is a striking feature to me.”

The torrent washed out bridges and the city’s water distribution line. It crossed over the five-lane U.S. 70 and eroded businesses’ foundations, causing them to collapse.

“I’ll be perfectly honest with you, I don’t know how to put that into context,” Prince said. “It’s not something that I ever really envisioned seeing in a place like this.”

The river’s rate of flow also boggles the mind of Jeff Wilcox, a hydrogeologist and UNC Asheville professor of environmental science. He pointed out that this flood and stream flow rates eclipsed the previous benchmark, the flood of 1916.

“I study this stuff, and I was blown out of the water,” Wilcox said.

‘This will be what everything is compared to’

The National Weather Service notes that besides the 13.21 inches of rain recorded for the Swannanoa station, which is 2.8 miles north of Swannanoa, Black Mountain’s creeks, as well as part of the Mount Mitchell watershed, drain into the valley.

Mount Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi River, stands at 6,684 feet and drains in several directions, including into the Swannanoa River Valley. The mountain received 11.22 inches of rain from Sept. 25-27.

David Easterling, director of the National Climate Assessment Technical Support Unit, part of NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information in Asheville, noted Helene did not “stall” over western North Carolina, or Swannanoa in particular. That has been the case with previous tropical storms that caused severe flooding.

“Helene was a dynamic, moving storm,” Easterling said. “It’s just the setup ahead of it, and then the storm itself was ideal for huge amounts of rain.”

Most areas near the escarpment received excessive amounts of rain due to “orographic lift,” Easterling said. That is an upsloping motion as the southerly flow hits the mountain escarpment and is forced to rise.

The Black Mountain area probably got additional rain from the same orographic lift from the Black Mountains, Easterling said. He said the precursor rain event of Sept. 25 did stall over the Swannanoa area, dropping at least an inch or two.

“This front provided a focusing mechanism so that when Helene got close enough, but still in the Gulf, the flow around Helene (counter clockwise) provided a conveyor belt-like setup, with moisture from the Gulf streaming directly at us,” Easterling said. “Then, as Helene moved north on a path to the west of Asheville, all the areas to the east of the eye continued to get huge amounts of rain and wind, and the upsloping provided more enhancement to the rainfall.”

As Asheville Watchdog previously reported, Helene has broken all records for rainfall and river flow rates. Easterling pointed out that Connestee Falls, a station near Brevard, got more than 30 inches of rain for the four days before and during Helene.

The City of Asheville has two reservoirs in the area, North Fork and Bee Tree. North Fork has two spillways and Bee Tree one, and they were flowing the morning of Sept. 27.

Swannanoa Valley Fire & Rescue Chief Anthony Penland said the dam systems performed as designed, protecting nearly all of Swannanoa from annihilation, a point reinforced by Clay Chandler, spokesperson for the Asheville Water Resources Department.

“The dams, and spillways, at Bee Tree and North Fork functioned exactly as they were designed,” Chandler said. He noted that North Fork’s auxiliary spillway has eight concrete “buckets” that are designed to tip once the water level reaches a certain point.

With the huge amount of rain that fell, the auxiliary spillway, which was completed in 2021, played a crucial role in protecting the valley below.

“Without the new spillway to release pressure, it is very likely North Fork’s dam would have failed,” Chandler said. “If that had happened, 6 billion gallons of water would have caused catastrophic loss of life and property.”

The flood’s force was jaw-dropping to Wilcox, the hydrogeologist, because it swept away buildings and homes that were designed to withstand a 100-year flood.

“It’s one thing to flood the Swannanoa RIver and you have to dig it out and wash it off,” Wilcox said. “But it’s another thing to just break it into pieces.”

Wilcox, who lives in east Asheville, said it’s painful to even talk about Swannanoa’s damage, and pointing out the geological history of the area remains difficult.

“So thinking about it geologically, the Swannanoa River Valley is there because of events like this,” Wilcox said. “If this was a 1,000-year rainfall event, that means that in the last million years, it’s actually happened 1,000 times. This has happened in the geologic past.”

Mill spurred development of cottages

The difference is that in many of the previous floods, not much was there.

Penland, who said he knew several of the local people who’ve been killed in the floodwaters and a landslide that hit the Grovemont area, was born and raised in Swannanoa. He did not have an official fatality count for the town, noting that the state is handling that tally.

As of Oct. 18, Buncombe County’s official count stood at 42 fatalities.

Asked why so much commercial and residential development was in harm’s way, Penland offered a short history lesson.

“Those buildings, that village right there, those houses were built in the 1920s,” Penland said, gesturing toward the mill village. “When Beacon Manufacturing came here in 1928, those were the original mill houses.”

Penland explained how the mill, Beacon Blankets, which closed in 2001, built two housing areas for its workers, the upper village to the east and the lower to the west.

Arson destroyed the plant, which took up more than a city block, in 2003. The homes remain, housing locals, including descendants of workers.

“I never thought in a million years that it would have got into this lower village right down here,” Penland said. “And I’m not saying it got into it — those houses were underwater, up to the rooftops.”

For millennia, humans have settled along waterways, as we need the water sources, and the land tends to be flatter.

“Living riverside like that in Appalachia — like a Chandler tire, like some of those shopping centers across from Ingles and stuff like that — that’s pretty typical,” Prince said, referring to prominent businesses in Swannanoa.

In the Appalachians, we don’t have a classic rainy or monsoon season. Rainfalls ebb and flow, and flooding events can be a few years apart or 50.

“You get an event like this as a one off,” Prince said. “It’s kind of variables that intersect with each other and make things go crazy. And it might not happen once in 100 years or more. It might happen a couple times within a short time span, and then you wouldn’t see it for hundreds of years.”

Penland said he and his firefighters started issuing warnings to residents in low-lying areas two days before Helene hit but after the precursor rains had caused minor flooding. They continued issuing warnings Thursday.

Firefighters and police drove throughout the Swannanoa area Friday morning, playing a message recorded in English and Spanish urging evacuation. That was around 4:45 to 5 a.m. — “to the point where the water was starting to come above the tires of the trucks,” Penland said.

They had to evacuate the main fire station, but were able to conduct 40 rescues that day, Penland said.

Some people heeded the warnings, which were also issued by the county and the National Weather Service. Some didn’t. One man said the storm likely wouldn’t be any worse than the 2004 flood that brought knee-deep water into his house, Penland said.

Usually tame streams turned into violent cascades. Places that flooded but survived the 2004 event no longer exist.

“We have a place off of Riverwood; it was called Opal Lane,” Penland said. “There may have been six, eight trailers in there. They’re gone.”

‘Nobody knew they were in harm’s way’

One of the original mill houses belonged to Karla Gay. Standing on Edwards Street last week, Gay was surrounded by 10-foot piles of flooring, wallboard and other debris lining both sides of the street, the remnants of 24 flooded single-story cottages gutted to the studs by residents and volunteers.

“My grandparents bought that house directly from Beacon Village in the ‘20s or so, and it’s been in our family since then,” Gay said. “My mother grew up in the house.”

When her grandparents bought the house, U.S. 70 wasn’t there.

“The property went all the way to the river,” Gay said. “It never flooded.”

The duplexes were one bedroom, with a living room, kitchen and bath. Monthly rent was $575 for one of her long-term tenants.

Gay, 58, owns a company that manages nonprofits that don’t have their own staff. She’s partnered with a resident of Edwards Avenue, Tissica Schoch, a vice president of finance for a consulting firm, to form savebeaconvillage.org, a nonprofit that will help residents rebuild their homes.

Schoch lives on the upper part of Edwards, just high enough to avoid flooding. She rode out the storm in an upstairs garage with her partner and their neighbors.

“All I could do was watch the river come over,” said Schoch, the project manager for savebeaconvillage.org.

Schoch said she was up all night before the storm, in part checking the 500-year floodplain.

“And my house and the house next to me, 122, should have been safe, even with that 500-year flood plain,” Schoch said. “And she got two or three inches of mud in her house at 122.”

Schoch and Gay said Edwards Avenue residents lacked flood insurance, and that’s why they’re fundraising.

“I would say, nobody knew they were in harm’s way,” Gay said. “The biggest flood in our lifetimes has been the one from 2004, and the water didn’t get close to these houses.”

Jared Riske, who owns Gone Fixin’ Home Improvement in New Bern, spent the week on Edwards Avenue with two of his teenage sons and a work crew, helping gut houses. He was paying his crew but not charging residents.

A couple of the houses were under water and lifted off their foundations, leaving them uninhabitable, Riske said.

“This is way worse than anything I’ve seen on the coast for a hurricane, and mainly it’s just because this was like a tidal wave hitting a town in the mountains,” Riske said.

Hoping to save family memories

Thanh Bui and Quintin Ho are unsure what they’ll do next.

Bui said she had no flood insurance. FEMA will pay for a hotel through early November, but the agency offered just $4,000 in assistance. She plans to talk to Samaritan’s Purse about assistance.

Ho said his mom is strong, but it’s hard to comprehend their situation.

“I’ve been trying to rack my brain on it, and honestly, I’m not too sure,” Ho said when asked about trying to rebuild their home. “I think she wants to. I mean, we don’t have many other options.”

Bui said that after the flood she found a man in the house trying to steal her bankbook and imitation gold silverware. She previously had no worries about living in her home.

Bui feels tied to the community. She’s seen kids from Black Mountain Elementary grow up and go off to college. They share their fond memories of her laughter and kindness in the lunchroom.

Now, she’s trying to salvage her own family’s memories.

“Mainly, I just worry about the pictures we lost,” Bui said. “That’s what I’m trying to get.”

Before she left the house and swam to Dunkin’ Donuts, Bui put her daughter’s college diploma up high inside the house. It got a little wet, but she’s hopeful it’ll dry out.

“The photos and stuff, it’s just…” she said, pausing. “That’s the main thing.”

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and Buncombe County. John Boyle has been covering Asheville and surrounding communities since the 20th century. You can reach him at (828) 337-0941, or via email at jboyle@avlwatchdog.org. To show your support for this vital public service go to avlwatchdog.org/support-our-publication/.

Related

The post Why did Swannanoa become Helene’s ‘ground zero’? Deadly combination of topography, development and a ‘tidal wave’ of water • Asheville Watchdog appeared first on avlwatchdog.org

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

White House officials hold prayer vigil for Charlie Kirk

SUMMARY: Republican lawmakers, conservative leaders, and Trump administration officials held a prayer vigil and memorial at the Kennedy Center honoring slain activist Charlie Kirk, founder of Turning Point USA. Kirk was killed in Utah, where memorials continue at Utah Valley University and Turning Point USA’s headquarters. Police say 22-year-old Tyler Robinson turned himself in but has not confessed or cooperated. Robinson’s roommate, his boyfriend who is transitioning, is cooperating with authorities. Investigators are examining messages Robinson allegedly sent on Discord joking about the shooting. Robinson faces charges including aggravated murder, obstruction of justice, and felony firearm discharge.

White House officials and Republican lawmakers gathered at the Kennedy Center at 6 p.m. to hold a prayer vigil in remembrance of conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

https://abc11.com/us-world/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Family, friends hold candlelight vigil in honor of Giovanni Pelletier

SUMMARY: Family and friends held a candlelight vigil in Apex to honor Giovanni Pelletier, a Fuquay Varina High School graduate whose body was found last month in a Florida retention pond. Giovanni went missing while visiting family, after reportedly acting erratically and leaving his cousins’ car. Loved ones remembered his infectious smile, laughter, and loyal friendship, expressing how deeply he impacted their lives. His mother shared the family’s ongoing grief and search for answers as authorities continue investigating his death. Despite the sadness, the community’s support has provided comfort. A celebration of life mass is planned in Apex to further commemorate Giovanni’s memory.

“It’s good to know how loved someone is in their community.”

More: https://abc11.com/post/giovanni-pelletier-family-friends-hold-candlelight-vigil-honor-wake-teen-found-dead-florida/17811995/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

NC Courage wins 2-1 against Angel City FC

SUMMARY: The North Carolina Courage defeated Angel City FC 2-1 in Cary, ending their unbeaten streak. Monaca scored early at the 6th minute, followed by Bull City native Brianna Pinto’s goal at the 18th minute, securing a 2-0 halftime lead. Angel City intensified in the second half, scoring in the 88th minute, but the Courage held firm defensively to claim victory. Pinto expressed pride in the win, emphasizing the team’s unity and playoff ambitions. Nearly 8,000 fans attended. Coverage continues tonight at 11, alongside college football updates, including the Tar Heels vs. Richmond game live from Chapel Hill.

Saturday’s win was crucial for the Courage as the regular season starts to wind down.

https://abc11.com/post/north-carolina-courage-wins-2-1-angel-city-fc/17810234/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed7 days ago

Lexington man accused of carjacking, firing gun during police chase faces federal firearm charge

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

Zaxby's Player of the Week: Dylan Jackson, Vigor WR

-

News from the South - Arkansas News Feed7 days ago

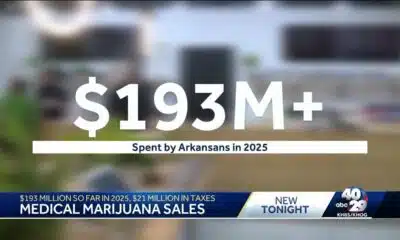

Arkansas medical marijuana sales on pace for record year

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

What we know about Charlie Kirk shooting suspect, how he was caught

-

Local News7 days ago

US stocks inch to more records as inflation slows and Oracle soars

-

Local News6 days ago

Russian drone incursion in Poland prompts NATO leaders to take stock of bigger threats

-

Local News Video6 days ago

Introducing our WXXV Student Athlete of the Week, St. Patrick’s Parker Talley!

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

Federal hate crime charge sought in Charlotte stabbing | North Carolina