News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Warren Wilson left out of NC Helene bill. Reason unclear.

The most recent Helene recovery package from the state allocated $500 million to help address remaining damage to Western North Carolina, more than $4 million of which went to small private colleges and universities in the area. Even so, Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, which says it sustained $12 million in damages, yet was not on the receiving end of any financial aid from the state.

The Swannanoa Valley in eastern Buncombe County experienced significant flooding from Helene with the river cresting at 26.1 feet, the highest point since 1916. Warren Wilson Provost and Dean of the Faculty Jay Roberts said 60 campus buildings experienced either roof or flood damage. FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers helped remove 70,000 cubic yards of debris at the school. The campus did not have drinking or running water for a substantial amount of time, he said.

Warren Wilson President Damián J. Fernández issued a statement voicing his disappointment with the legislation’s exclusion of the college. He asked lawmakers to reconsider providing support when the legislature reconvenes later this month.

[Subscribe for FREE to Carolina Public Press’ alerts and weekend roundup newsletters]

Montreat College, located just 12 miles east of Warren Wilson, also experienced significant damage. Its gymnasium was the most impacted, and the college estimated it would take up to eight months to restore. Lees-McRae College in Banner Elk described its damage as moderate to Carolina Public Press in October. Three of its buildings were damaged by fallen trees, including a residence hall.

But Montreat and Lees-McRae each received $1.5 million in the latest relief package. In addition, Mars Hill University received $500,000. Brevard College, Gardner-Webb University and Lenoir-Rhyne University each received $250,000.

And despite initially being allocated $1.5 million when the House appropriations committee introduced the bill in May, Warren Wilson ultimately received nothing in the final version.

State representatives in the area are saying the change-up was a political move.

When the package was on the floor for a vote June 26, when it ultimately passed unanimously, state Rep. Lindsey Prather, D-Buncombe, pointed out Warren Wilson’s lack of funding. Prather represents the 115th district, where Warren Wilson resides.

“I’m confused and I’m disappointed and I’m very frustrated,” Prather said on the floor. “It certainly feels like the institutions in Buncombe — which as a whole, received the most amount of damage — are being carved out of this bill. I hope that this isn’t politicization of recovery. It’s hard not to read it that way.”

In addition to the lack of funding to Warren Wilson, Prather said an aspect of the funding allocated to the larger public universities also struck her as odd.

Western Carolina University and Appalachian State University both received $2 million, whereas UNC-Asheville, also located in Buncombe County, has to share its $2 million with the North Carolina Arboretum. The arboretum is an affiliate of the UNC System, but is not directly under UNC-Asheville or any individual institution.

Seeing as Montreat, a conservative religious college that is also located in Buncombe County, Prather told CPP these disparities make it seem as though institutions that are perceived as more progressive are being treated unfairly.

While Warren Wilson is affiliated with the Presbyterian Church and a member of the Association of Presbyterian Colleges and Universities, Roberts said he would describe the school as one with a historic religious affiliation rather than a religious college.

Warren Wilson was one of eight private colleges and universities included in the original bill proposed by the House. Johnson C. Smith University, an HBCU in Charlotte, was also initially positioned to receive $500,000 but was later removed. While Charlotte did not get the brunt of the storm, JCSU reported it had to close a residence hall due to water damage from Helene, leading the university to relocate more than 200 students.

When the legislation made its way to the Senate, all higher education institutions were stripped from the bill entirely. It wasn’t until the bill landed in the conference committee, a temporary joint committee created for the House and Senate to work out the bodies’ differences on a piece of legislation, that the six private schools and three UNC System schools made it in the final cut.

The conference committee was composed of four Republican representatives and four Republican senators. None of them responded to multiple requests for comment from CPP.

Prather said the makeup of the committee was disappointing but not surprising based on the current leadership in the legislature.

“Republican leaders in the legislature were the first to say that we all need to pull together for Western North Carolina and we can’t politicize this, we all need to support our brothers and sisters,” she said. “And then they go and form a conference committee with only Republicans, including some Republicans that don’t live in Western North Carolina.”

State Rep. Eric Ager, D-Buncombe, represented Warren Wilson in past iterations of the state’s districts. Now the college falls under Prather’s jurisdiction, but it wasn’t easy for her to get there.

Ager believes it’s Prather’s election that made Republicans strip Warren Wilson from the recovery package.

When North Carolina was redistricted in 2023, Republicans used what Ager called a “donut strategy,” leaving Asheville as its own district in the middle and drawing two districts that lean more conservative, the 114th and 115th, around the city. Despite the 115th district appearing to be a Republican stronghold, Prather won the seat by a tight margin in 2024.

It’s hard to see any other reason why Warren Wilson was left out of Helene funding than politics, Ager said.

“That’s the only reason I can think of that makes Warren Wilson different, because the reality of it is they suffered a lot more damage than the other schools that were on the list,” he said.

Warren Wilson leaders were surprised by the college’s exclusion because the school’s communication and relationships with lawmakers were positive throughout the storm and recovery efforts, Roberts said. They don’t want to speculate on why Warren Wilson was cut, and they’re still working to get answers several weeks later.

The college is attempting to be sensitive in the way it lifts up concerns about being excluded, Roberts said. He hopes all Americans understand that natural disasters are not political events.

“Natural disasters are when every American — regardless of where they come from, what their political affiliation is — gets support because we come together as a country during times like this,” he said.

“I think that should be an understood, baseline expectation for everyone in whatever region of the country you come from, and that’s certainly our expectation here.”

While the storm had a great impact on Warren Wilson, Roberts emphasized the impact Warren Wilson has on the state — 40% of their students are from North Carolina, another 40% are Pell Grant eligible and the college’s presence contributes $50 million to North Carolina’s economy, he said.

Ager and Prather both said they hope proposed funding for Warren Wilson will be revisited, though they aren’t sure it would be a successful endeavor.

“I always worry that they’re going to make a political decision rather than a common sense policy decision,” Ager said.

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The post Warren Wilson left out of NC Helene bill. Reason unclear. appeared first on carolinapublicpress.org

Note: The following A.I. based commentary is not part of the original article, reproduced above, but is offered in the hopes that it will promote greater media literacy and critical thinking, by making any potential bias more visible to the reader –Staff Editor.

Political Bias Rating: Center-Left

This article presents a critical perspective on the state legislature’s handling of disaster relief funding, highlighting potential political motivations behind the exclusion of Warren Wilson College from aid. The coverage emphasizes concerns from Democratic state representatives and affected institutions, framing Republican-led decisions as possibly partisan and unfair. The tone leans toward advocacy for equitable aid and accountability in government, common in Center-Left reporting, but it maintains factual reporting and quotes multiple viewpoints without overt ideological rhetoric. Thus, it exhibits a moderate left-leaning bias focused on social fairness and government oversight.

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

NC congressional Republicans seek removal of magistrate who freed suspect in Charlotte rail killing

SUMMARY: North Carolina’s 10 Republican U.S. House members demand the removal of Magistrate Teresa Stokes, who released repeat offender DeCarlos Brown Jr., accused of murdering Ukrainian refugee Iryna Zarutska on Charlotte’s light rail. Brown, with 14 prior charges, was free on a misdemeanor-related promise to appear in court. Congressman Tim Moore condemned Stokes for failing to protect the public. State Auditor Dave Boliek announced an immediate investigation into Charlotte Area Transit System’s (CATS) safety protocols. Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles condemned the attack and pledged enhanced policing. Lyles recently won the Democratic primary and will face Republican and Libertarian opponents in November, with crime a key issue.

The post NC congressional Republicans seek removal of magistrate who freed suspect in Charlotte rail killing appeared first on ncnewsline.com

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Who is eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine this year? We’ll find out more this month

SUMMARY: Eligibility for the COVID-19 vaccine this year is uncertain and causing confusion. The FDA recommends it for people 65+ and those 6 months+ with pre-existing conditions, requiring a doctor’s note. However, North Carolina currently allows pharmacists to administer the vaccine only to those 18+ with a prescription. The emergency use authorization ended August 27, complicating access. The CDC’s advisory panel (ACIP) will meet September 18 to finalize recommendations, which may broaden eligibility. Public health officials worry that limited access and the need for doctor’s notes could hinder vaccination efforts. Updates are expected mid-September; local health departments and primary care physicians are key resources.

As the cooler months approach, respiratory illnesses are front of mind, which includes COVID-19. Unlike years past, as of now, not everyone can walk up to a pharmacy and get the shot. WRAL’s Ashley Rowe talks about where things stand, why there’s confusion and when you’ll find out for sure if you’re eligible this season.

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed

Legal experts share insight on court proceedings following deadly attack on Charlotte light rail

SUMMARY: Legal experts and officials are responding to the stabbing death of 23-year-old Ukrainian refugee Irina Our Czar on a Charlotte light rail train. Suspect Carlos Brown Jr., 34, faces federal and first-degree murder charges. Brown has a criminal record and mental health issues, complicating the case. His mother expressed concerns about his aggressive behavior post-prison, including an involuntary commitment order and a recent 911 misuse arrest. Wake County leaders highlight the challenge of addressing mental health within the justice system, noting inadequate resources and the Wake County Jail’s role as a primary mental health provider. Reforms aim to improve pretrial detention and court procedures.

Legal observations are flying in in the aftermath of the savage, unprovoked attack on a Charlotte light rail last month that left a young Ukrainian refugee dead.

https://abc11.com/post/legal-experts-share-insight-court-proceedings-following-deadly-attack-charlotte-light-rail/17781644/

Download: https://abc11.com/apps/

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ABC11/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abc11_wtvd/

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@abc11_wtvd

TIKTOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@abc11_eyewitnessnews

X: https://x.com/ABC11_WTVD

-

News from the South - Texas News Feed6 days ago

Texas high school football scores for Thursday, Sept. 4

-

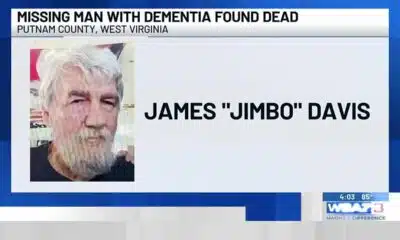

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

Missing man with dementia found dead

-

News from the South - Louisiana News Feed5 days ago

Portion of Gentilly Ridge Apartments residents return home, others remain displaced

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed5 days ago

Hanig will vie for 1st Congressional District seat of Davis | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed5 days ago

Alabama state employee insurance board to seek more funding, benefit changes

-

The Conversation6 days ago

Scientific objectivity is a myth – cultural values and beliefs always influence science and the people who do it

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed5 days ago

WV Supreme Court will hear BOE’s appeal in vaccine lawsuit — but not right away

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed5 days ago

More details expected on ICE raid at south Georgia plant | Georgia