News from the South - Texas News Feed

Trump’s policies strike fear into Texas immigrant communities

“A lot of fear going on”: Texas immigrant community on edge during Trump’s first weeks

““A lot of fear going on”: Texas immigrant community on edge during Trump’s first weeks” was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Sign up for The Brief, The Texas Tribune’s daily newsletter that keeps readers up to speed on the most essential Texas news.

EL PASO — On a recent windy, cold afternoon in this border city, dozens of people gathered at a park for an immigrant rights demonstration to denounce the Trump administration’s immigration policies. Some held signs reading: “Immigrants Make America Great.”

Alan, a local police officer, and his wife came and held a Mexican flag. He said he joined the demonstration because he worries about his father, an undocumented immigrant who works at a farm in southern New Mexico.

Alan said he voted for Donald Trump because of worries about the economy and because he believes Trump is pro-police and would combat the public’s negative perception of law enforcement. He said he believed Trump’s promises to make everyday items affordable for middle-class families.

But after two weeks of Trump in the White House, Alan — who declined to give his last name because he fears retaliation against his father — said he now regrets his vote. Partly because he was angered when Trump granted clemency to people involved in the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

And, he added, “I just don’t agree with how he’s going about the mass deportations.”

In his first week in office, Trump issued nearly a dozen executive orders, many of them targeting the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. The Trump administration gave federal officers a national quota to arrest at least 1,200 undocumented immigrants every day — double the highest daily average in the past 10 years.

The sudden appearance of immigration officers combing the streets of Texas cities, which set off a flurry of social media posts as people documented their presence, has put undocumented Texans, educators, religious leaders, and business owners, among others, on edge, bracing themselves for the worst.

“There’s definitely a lot of fear going on,” said Ramiro Luna of Somos Tejas, a Dallas-based nonprofit focused on Latino civic engagement. “Our community feels threatened, and while we’re doing our best to provide information and peace of mind, it’s incredibly difficult. People are afraid to come to any gathering — even to get basic necessities.”

Undocumented and legal immigrants alike describe feeling anxious, angry, hopeless. Some say they’re changing their daily routines to reduce their chances of being swept up by immigration agents on the prowl.

Some classrooms once filled with the chatter of students now sit eerily quiet. Many undocumented parents, terrified of immigration raids, are keeping their children home. Some families, afraid of even the shortest drive, consolidate trips. Stepping outside feels risky.

Undocumented immigrants who have crossed the border without permission can be prosecuted for illegal entry, which is a misdemeanor. Immigrants who entered the U.S. legally but overstayed their visa have violated administrative immigration rules, which is not considered a crime. Federal courts have also ruled that living in the U.S. without legal status is not a crime.

Still, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said the U.S. government now considers undocumented immigrants criminals — whether or not they have been convicted of a crime.

“I know the last administration didn’t see it that way, so it’s a big culture shift in our nation to view someone who breaks our immigration laws as a criminal, but that’s exactly what they are,” she said.

Caitlin Patler, a public policy associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, said Trump and other Republican leaders dehumanized immigrants during last year’s election cycle and constantly linked them to crime.

“Immigrants were scapegoated throughout the entire presidential campaign,” she said. “They’re convinced they are part of the crime problem, even though all evidence points to the contrary.”

Deported in the Rio Grande Valley

Geovanna Galvan is reeling from what she said is the unfair deportation of her father — who was recently cited for impeding traffic by a police officer from Primera, a small town in Cameron County.

On Wednesday, Jaime Galvan Sanchez, 47, was driving a tractor on a road near the farm where he’s worked for more than 10 years when a police officer stopped him. Less than 24 hours later, he was deported to Mexico, Galvan said.

Galvan, 29, said the police officer asked her father if he had any proof of legal residence. When he said he didn’t, the officer called federal immigration authorities.

Galvan Sanchez was able to call his daughter to tell her he was being detained by U.S. Border Patrol. She tracked his cellphone to a Border Patrol station in Harlingen and drove there with documents — utility bills, tax documents and property records — to prove he had lived in the U.S. for more than two decades, but she said officers didn’t allow her to see her father.

She was told her father would be allowed to call her, but she didn’t hear from him until the next morning when he called from Reynosa, a Mexican border city across the Rio Grande from McAllen.

“They just treated him as if he was nothing,” Galvan said.

She said immigration authorities deported him based on a misdemeanor theft conviction from 1991. But she is adamant that he couldn’t have committed the crime because he would’ve been 14 at the time and he arrived in the U.S. from Mexico in his 20s.

“My dad is not that person,” she said.

Her biggest worry is her 10-year-old brother, who suffers from epilepsy and hyperinsulinemia –– an excess of insulin in the blood –– and depends on their dad’s income to afford his medication.

“It’s not fair they’re separating families, especially when you have children or kids that need their parents,” she said. “My little brother needs my dad.”

Both her father and mother are undocumented but prior to this week, she had never been worried that her family would be vulnerable to deportation because she believed authorities would only target people with criminal records.

“Now my little brother doesn’t want to go to school because he thinks that when he comes home, my mom is not going to be there,” she said.

Primera officials did not respond to the Tribune’s request for comment but issued a statement on Facebook stating that its police officers do not participate in deportation efforts.

On Friday, immigration authorities allowed Galvan Sanchez to re-enter the U.S. with an ankle monitor and a notice to appear before a judge in March, according to his attorney, Jaime Diez.

Anxiety in schools

The anxiety reaches deep into schools. Many parents have reached out to ImmSchools, a nonprofit organization that supports educators and immigrant students, for guidance, unsure how to comfort students or reassure parents that school is still safe.

Teachers, too, are struggling. At a recent virtual Know Your Rights session by the nonprofit about 150 parents and educators shared stories of how fear has upended their daily routines — students breaking down in tears, fearful that their parents will be deported while they sit in class.

The Trump administration also has said that immigration agents are allowed to enter public schools, health care facilities and places of worship to arrest undocumented immigrants. Previous administrations had prevented agents from entering those sites.

“A family mentioned that they are eight minutes away from school, but even those eight minutes from and to [school] felt like too much,” said Lorena Tule-Romain, co-founder of ImmSchools. “They were asking if there are online schools or can schools provide virtual zoom classes instead.”

For students, the emotional toll is immediate. Teachers have told the organization that some children are withdrawn, others refuse to participate in class and many are visibly anxious.

“How they show up in the classroom, their mental health, their confidence — it’s all affected by their immigration status,” Tule-Romain said.

Brenda Gonzalez, the organization’s Texas-based associate director, said teachers are reporting low attendance in classes. She said absences put students at risk of falling behind or even being held back because students have to complete a certain number of hours to be promoted to the next grade level.

Legal advice for immigrants

Dallas-based immigration attorney Daniel Stewart said permanent residents are rushing to apply for citizenship, while immigrants who have been given Temporary Protected Status, especially Venezuelans, are desperate for more permanent protections, fearing the next policy change could strip them of their legal status.

Temporary Protected Status is a program Congress created in 1990 that allows immigrants from countries struck by natural disasters or deemed too dangerous by the government to live and work in the U.S.

“There’s a lot of trepidation,” Stewart said. “People are worried about what will happen to their pending cases and whether they’ll still be protected under new policies.”

Stewart notes that Trump’s more aggressive executive orders and rhetoric are fueling uncertainty. For undocumented immigrants, he stresses the importance of staying out of legal trouble because even minor offenses could lead to detention and deportation.

“Unfortunately, many undocumented individuals have no path to protection. It’s tough,” he said. “My advice is obey the law, stay informed, and seek legal counsel when needed.”

Mexican government offers app for emergencies

At the Mexican Consulate in Dallas, the phone keeps ringing — worried voices asking urgent questions: What should I do if immigration officers stop me? Who do I call if I’m detained? Is it safe to go to work?

In response, the consulate has ramped up its efforts to support Mexican nationals living in the U.S., expanding legal services and launching new tools to ensure immigrants have access to help when they need it most.

Consul General Francisco de la Torre says he is trying to reassure the community that they are not alone.

“We stand with you, especially during these dark, challenging times,” he said.

One of the Mexican government’s efforts to help its citizens in the U.S. is the ConsulApp Contigo, a mobile application available on Android and iOS that lets users store family contact information, and if they are detained, a single press of a button alerts their relatives and the nearest Mexican consulate.

“It’s not a panic button,” de la Torre said, “but it ensures that your loved ones and the Mexican government know something is happening.”

The consulate has a network of more than 300 law firms across the U.S. to provide legal assistance, particularly in immigration, criminal, and family law cases. In Dallas-Fort Worth alone, hundreds of lawyers are available to offer guidance — no appointment necessary.

As fear spreads, so does misinformation, especially on social media, said de la Torre. Rumors of massive workplace raids have fueled panic, with some immigrants afraid to leave their homes.

De la Torre urges the community to rely on verified sources for information. He said they maintain regular communications with the local Immigration and Customs Enforcement field office, which sits just across the freeway from the consulate.

“Our role is not to cut off dialogue — it’s to improve it,” he said. “Clear communication allows us to better protect the human rights of our community.”

The consulate provides a 24-hour emergency services for cases involving detention, deportation, repatriation, and rights violations. Mexican citizens in Texas can call 520-623-7874 for immediate assistance.

Disclosure: Facebook has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2025/01/31/texas-immigrants-undocumented-trump-deportation/.

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.

News from the South - Texas News Feed

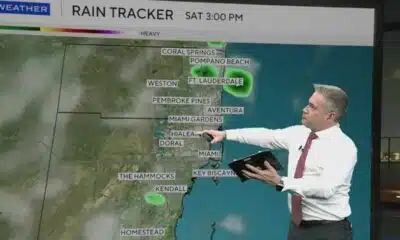

La Niña now expected to last all winter

SUMMARY: For the first time this year, La Niña is now forecast to last throughout the entire winter, with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center giving it a 54% chance for December-February. Previously, ENSO Neutral was favored for winter. La Niña occurs when sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific are 0.5ºC below average, typically pushing the Pacific Jet Stream north, causing drier, warmer conditions in the southern U.S. and wetter areas in the Pacific Northwest. Last winter, a weak La Niña brought a record warm December but cooler January-February, below-average rainfall, snow in Austin, and more freezes than normal. Another mild La Niña winter is expected for Central Texas.

The post La Niña now expected to last all winter appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Texas high school football scores for Friday, Sept. 12

SUMMARY: Lake Travis dominated Midland Legacy 59-13 in a spirited farewell to the old Cavalier Stadium before renovations force home games to move to Dripping Springs High School. Across Central Texas, notable district wins included Anderson over College Station (37-14), Bowie against Glenn (38-14), and Dripping Springs edging Harker Heights (31-26). High-scoring games saw McNeil top Westwood 70-45, and Hutto defeat Cedar Ridge 63-49. Close contests included Vista Ridge’s 30-29 win over Round Rock and Austin LBJ’s 34-33 overtime victory against Wimberley. The article also features an extensive list of scores from other Texas high school football games.

The post Texas high school football scores for Friday, Sept. 12 appeared first on www.kxan.com

News from the South - Texas News Feed

Safe Central Texas meet-up spots for online purchases

SUMMARY: The Lockhart Police Department created its first Community MeetUp Spot for safe internet purchase exchanges after a man stole shoes during a transaction. Located in the police station parking lot at 214 Bufkin Lane, it offers a secure, monitored area encouraging buyer and seller safety. Positive community feedback inspired the initiative. Several Central Texas police departments—including Georgetown, Cedar Park, Round Rock, Pflugerville, Manor, Austin, and Kyle—also provide designated or informal safe exchange spots. The Austin Police emphasize researching buyers/sellers, trusting instincts, and following safety tips such as taking photos, noting license plates, meeting in public areas, and keeping personal info private.

The post Safe Central Texas meet-up spots for online purchases appeared first on www.kxan.com

-

News from the South - North Carolina News Feed6 days ago

Reagan era credit pumps billions into North Carolina housing | North Carolina

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed6 days ago

Amid opposition to Blount County medical waste facility, a mysterious Facebook page weighs in

-

News from the South - South Carolina News Feed6 days ago

South Carolina’s Tess Ferm Wins Miss America’s Teen 2026

-

News from the South - Kentucky News Feed6 days ago

3 states push to put the Ten Commandments back in school – banking on new guidance at the Supreme Court

-

News from the South - West Virginia News Feed7 days ago

National Grandparents Day (9-7-25) and the special bond shared with their grandchildren

-

Local News6 days ago

Duke University pilot project examining pros and cons of using artificial intelligence in college

-

Local News7 days ago

Marsquakes indicate a solid core for the red planet, just like Earth

-

Mississippi News Video5 days ago

Interview: Come see Baptist at WTVA Senior Health Fair